Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became…

Australia minimum wage decision 2023 – some relief for lowest paid but real cuts for others

On June 2, 2023 Australia’s minimum wage setting authority – the Fair Work Commission (FWC) issued their decision in the – Annual Wage Review 2022-23 – which provides for wage increases for the lowest-paid workers – around 0.7 per cent of employees (around 75 thousand) in Australia. In turn, around 20.5 per cent of all employees, who are on the lowest tier of their pay award (grade) receive a flow-on effect. The FWC determined that sought to protect the real living standards of the lowest-paid workers in the nation after receiving a ‘direction’ from the new Federal Labor Government to do so. While the small number of workers who actually receive the FMW were largely protected from the current inflation-erosion of their purchasing power (although not compensated for losses over the last year), the larger group of workers on statutory awards who earn the minimum award rate went backwards in real terms as a result of the decision. The major employer groups argued for very low nominal rises, while at the same, as they are enjoying booming profits. A scandalous indictment of our system.

In this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017) – I outlined:

1. Progressive minimum wage setting principles.

2. The way staggered wage decisions (annually) lead to falling real wages in between the wage adjustment points.

I won’t repeat that analysis here. But it is essential background to understanding why the decisions taken by Fair Work Australia have been inadequate for a long time.

Who is affected?

The FWC notes that:

The NMW only applies to a very small proportion of the workforce: only 0.7 per cent of employees are paid the NMW. Approximately 20.5 per cent of employees are paid in accordance with minimum wage rates in modern awards. There are some additional categories of employees who are also affected by the Review in a less direct way by Review outcomes being ‘flowed on’ by various means. However, these categories of employees are small in number. The Panel’s decision will therefore operate upon the wages of about a quarter of the Australian employee workforce.

That relevant figures are as at the most recent estimate (August 2022):

1. Total employees: 10741.2 thousand.

2. Total employees on National Minimum Wage: 0.7 per cent or 75.2 thousand.

3. Total employees on minimum award conditions: 20.5 per cent or 2,201.9 thousand.

4. Number of workers affecting by Fair Work Commission decision: 27.5 per cent or 2,277 thousand

In other words the cohort that benefits from the higher nominal wages awarded by the FWC are “small in number”.

Further, the impact via total wages of the FWC on the overall CPI is miniscule despite the RBA governor using the FWC decision as his latest ruse to demonstrate dangerous wage pressures.

Trying to suggest that the mininum wage decision would be inflationary was an act of desperation from the governor and come September when his term of office is up we can only hope the federal treasurer who appoints the RBA head sends him packing.

Where the parties stand

The FWC received bids (submissions) from various parties in the process of making its decision.

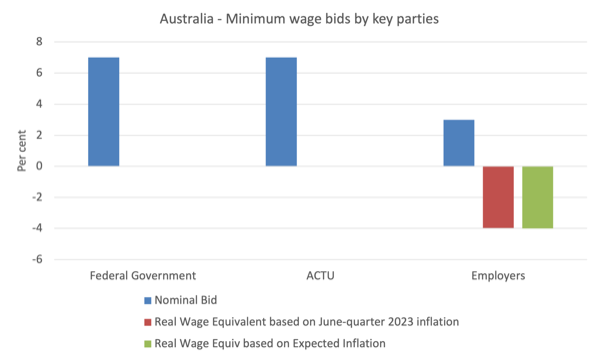

The follow graph summarises the key submissions from the Federal government (7 per cent increase), the Australian Council of Trade Unions (7 per cent increase) and the employer groups who the FWC said “Most employer groups which advanced any specific proposal for wage increases proposed that the increase should be 3 per cent or more but less than 4 per cent.”

The FWC rejected the employer submissions saying:

The adoption of wage increases in this range would, we consider, give insufficient weight to the considerations concerning relative living standards and the needs of the low paid.

The red bars in the graph show the implications in real terms of those bids based on the June-quarter 2023 inflation rate, which means, in an environment of accelerating inflation, the impact is biased downwards.

The green bars show the implications for the real wage from the FWC decision based on what the RBA expects the peak inflation to be (about).

So business wanted the lowest-paid workers and those most vulnerable to the current cost-of-living crisis to endure sizeable real wage cuts of around 4 per cent.

At the same time, corporate profits are at record levels.

Notably, for the first time in a decade or so, the Federal government (now a Labor government) supported a wage increase “which would preserve the level of their real wages” for the lowest wage workers, which was in line with the submission of the ACTU.

The Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) Decision

In its 2023 decision – Fair Work Australia wrote:

… the Panel has placed significant weight on the impact of the current rate of inflation on modern award-reliant employees. The Panel found that the decline in real wages amongst the modern award-reliant has had significant adverse effects on the low paid, causing a decline in living standards, financial pressure on households and, for some household types, a likely incapacity to meet basic budgetary needs. Because of the make-up of the modern award-reliant cohort, these adverse effects of the high rate of inflation will have disproportionately affected female employees and employees in less secure employment …

… the Panel concluded that there was no evidence in Australia of a wage-price spiral despite a very tight labour market … The Panel was unaware of any concrete evidence that increases to modern award minimum wage rates have had a material spillover impact on pay-setting behaviour for those whose pay is set by enterprise agreements or individual negotiation …

The step we will take is to align the NMW with the current C13 rate, which is the lowest award rate which, apart from exceptions in a small number of awards, may apply to employees in respect of ongoing employment. This will result in a modest wage adjustment of 2.7 per cent …

The Panel has decided to further increase the rate of the NMW by 5.75 per cent having regard to current circumstances … These increases will take effect from the first full pay period on or after 1 July 2023. Having regard to the negligible proportion of the workforce to which the NMW applies, the Panel considered that the outcome will not have discernible macro-economic effects.

So to summarise:

1. The FWC made a modest realignment in the parities between those workers on the FMW and those who are earning the lowest wage in their award – this is the 2.7 per cent increase component.

2. Then the FWC awarded a 5.75 per cent increase in the FMW and all minimum award wages.

3. So the 0.7 per cent of employees on the FMW, they gained an 8.55 per cent nominal wage rise.

4. So the lowest paid workers will have their real purchasing power preserved even though the purchasing power losses from the last year of inflation are gone forever.

5. However, for the 2.2 million workers who are on minimum awards they will take a real wage hit over the next 12 months in addition to the losses they have incurred over the last 12 months.

The FWC did, however, reject the employer groups desire to seriously cut real wages for the most vulnerable workers – at a time when corporate profits are booming and some segments of capital are making extraordinary gains as a result of the War in Ukraine and the inflationary chaos that created.

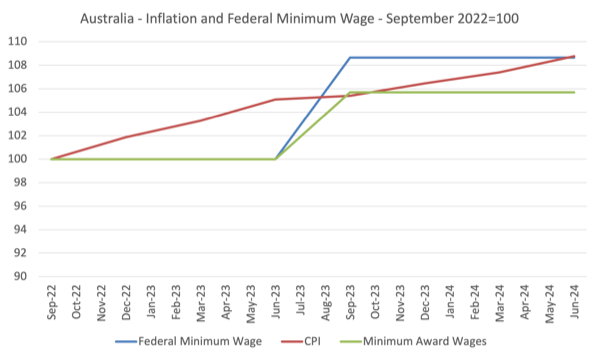

The following graph demonstrates the relationship between the FMW and the CPI movements from the time of the last adjustment (September-quarter 2022) to the end of the next period (June-quarter 2024).

The inflation between the September-quarter 2022 to the June-quarter 2023, eroded the real purchasing power of the Federal Minimum Wage and those losses are permanent.

The latest adjustment, which will impact from the September-quarter 2023 see the FMW more than fully adjusted (at that point) for the expected inflation and the ongoing inflation will steadily erode that purchasing gain until the June-quarter 2024.

The purchasing power gains in the next year will however not offset the purchasing power losses incurred in the past year.

For the vast bulk of minimum award wage workers, the real purchasing power losses incurred in 2022-23 are compounded by losses in the 2023-24 year as the 5.7 per cent increase will not be sufficient to counter the expected inflation rate in the year ahead

The FWC could easily build into the system, a feature that is common on most multi-period bargains, escalation.

That is, they could easily index wages to the quarterly inflation rate which would better protect real wages.

Real wage increase for lowest paid workers

Now what is the impact of a 8.6 per cent increase in the FMW?

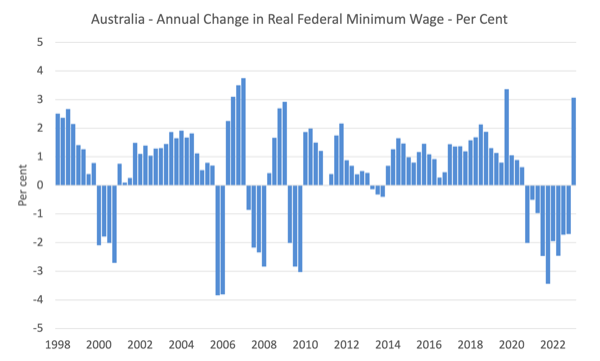

If we assumed all relevant workers were granted the increase on July 1, 2021 then the following graph shows the annual percentage change in the real National Minimum Wage since the September-quarter 1998 up to September-quarter 2023 (the first quarter the new level will be applicable).

The situation is not as good though for the workers who are on minimum award wages as opposed to being protected under the FMW – the former only received a 5.3 per cent increase and endured an ongoing real wage cut.

Staggered adjustments in the real world

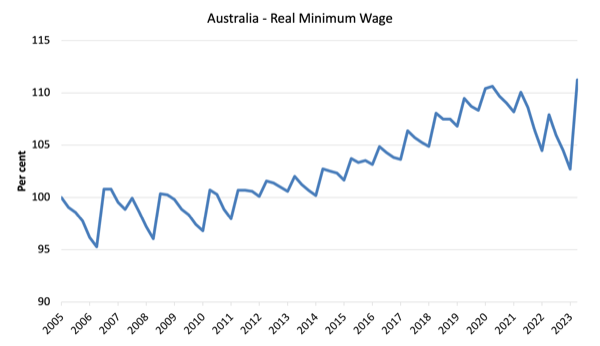

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (FMW) since the June-quarter 2005 extrapolated out to September-quarter 2023 (the quarter in which the recent decision will start impacting).

This is the FMW expressed in purchasing power terms.

You can see the saw-tooth pattern that the theoretical discussion I provided in this blog post – Australia’s minimum wage rises – but not sufficient to end working poverty (June 6, 2017) – describes.

Each period that curve heads downwards the real value of the FMW is being eroded. Each of the peaks represents a formal wage decision by the Fair Work Commission.

You can gauge the annual growth in the real wage by comparing successive peaks.

The decisions since 2012 have provided for some modest real income retention by these workers although it depends on how inflation is measured.

You can also see the troughs became shallower between 2012 and 2016 than in the past because the inflation rate moderated as a result of the GFC and the austerity since that has kept economic activity at moderate levels.

In more recent years the peak-trough amplitude has risen again and the FMW adjustments have failed to redress the purchasing power erosion to the nominal FMW even though each adjustment provides some immediate real wage gain for workers, those gains are ephemeral and the inflation process systematically cuts the purchasing power of the FMW significantly by the time the next decision is due – these are permanent losses.

As a result of the most recent decision, the new peak in the FMW will return the purchasing power to a level not seen since 2020.

FMW moves closer to the ‘living wage’ as a result of the FWC decision

There was a lot of discussion about a “fair” minimum wage and the concept of a living wage, which is often considered to be 60 per cent of the median wage.

This is sometimes expressed as the 60 per cent of median income poverty line.

The Fair Work Commission agreed that there were many workers in highly disadvantaged situations and contested the claims from the employers that the Commission had no role to play in setting living standards.

However, they did say that:

Nonetheless, at least for those employees of the NMW who do conform to any of the household types, the NMW cannot be said to constitute a ‘living wage’ which meets the basic MIHL standard. During the period of operation of the FW Act, it does not appear that the NMW has ever been set with this purpose in mind.

Yet, it remains that the ‘living wage’ concept is a often used benchmark for assessing how our lowest paid workers are tracking.

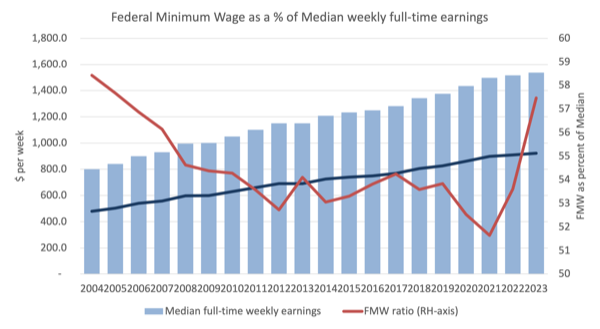

The following graph shows Median weekly earnings of full time employees from 2004 to 2023 (blue bars) and the Federal weekly minimum wage as a proportion of the median (red line, right-axis, per cent).

For 2022 median earnings I extrapolated the annual growth from 2021-22, which is likely to understate the outcome.

The dark blue line is the 60 per cent of median income poverty line.

Since 2010, this desired ratio has languished well below 60 per cent, which is the benchmark that is universally used to denote a ‘poverty threshold’.

It is currently at 57.5 per cent and the new FMW decision increased it by 4.1 points – a substantial adjustment in a positive direction.

What is the weekly shortfall?

Conclusion: The Federal Minimum Wage is around $39 per week shy of reaching the 60 per cent of median benchmark.

That should put the claims from the employer groups that anything more than a 3-4 per cent adjustment in the FMW would be desirable into perspective.

Lowest-paid workers improve relative to other workers but all workers still fail to share in productivity growth

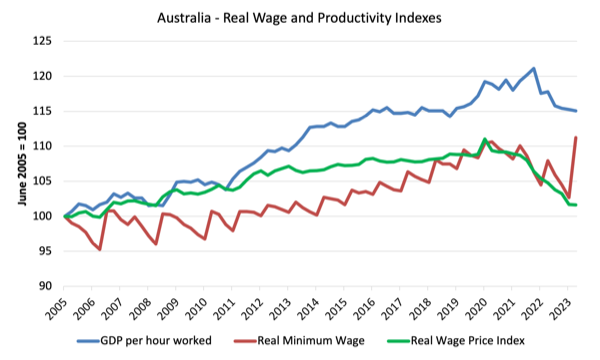

Another perspective is to compare the movement in the Federal Minimum Wage with growth in GDP per hour worked (which is taken from the National Accounts). GDP per hour worked is a measure of labour productivity and tells us about the contribution by workers to production.

Labour productivity growth provides the scope for non-inflationary real wages growth and historically workers have been able to enjoy rising material standards of living because the wage tribunals have awarded growth in nominal wages in proportion with labour productivity growth.

The widening gap between wages growth and labour productivity growth has been a world trend (especially in Anglo countries) and I document the consequences of it in this blog post – The origins of the economic crisis (February 16, 2009).

But the attack on living standards has targetted more than the bottom end of the labour market, although the minimum wage workers have certainly been more deprived of the chance to share in national productivity growth than other workers.

The current FWC decision provides some relief to that trend.

The following graph shows the evolution of the real Federal Minimum Wage (red line), GDP per hour worked (blue line), and the Real Wage Price Index (green line), the latter is a measure of general wage movements in the economy.

The graph is from the June-quarter 2005 up until September-quarter 2023 (indexed at 100 in June 2005 and extrapolated as above out to September 2023).

By June 2022, the respective index numbers were 115.1 (GDP per hour worked), 101.6 (Real WPI), and 111.2 (real FMW).

All workers have failed to enjoy a fair share of the national productivity growth. However, the most recent FWC decision has seen the lowest paid workers improve their position relative to other workers.

Like all graphs the picture is sensitive to the sample used. If I had taken the starting point back to the 1980s you would see a very large gap between productivity growth and wages growth, which has been associated with the massive redistribution of real income to profits over the last three decades.

In my view this represents the ultimate failure of capitalism.

Conclusion

This year’s adjustment of the federal minimum wage (and associated minimum wages in the awards) by the Fair Work Commission is one of the better decisions in recent years, partly because a full cost-of-living adjustment was supported by the Federal Labor government.

Previous conservative governments have refused to support such relief for the lowest-paid workers.

However, while the small number of workers who actually receive the FMW were largely protected from the current inflation-erosion of their purchasing power (although not compensated for losses over the last year), the larger group of workers on statutory awards who earn the minimum award rate went backwards in real terms as a result of the decision.

In terms of the accepted 60 per cent of median full-time weekly earnings (the ‘Living Wage’ concept), the Federal Minimum Wage remains some $39 per week shy of reaching that benchmark, which is the commonly accepted poverty line for workers.

However, the recent decision moved the FMW much closer to that benchmark than previous decisions.

Of course, the employers were aghast at the decision while at the same time pocketing record profits as a result of their profit gouging.

Fortunately, their greed was mostly rejected by the Commission.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill. This is an outstanding blog contribution. I note the comment: “In my view this represents the ultimate failure of capitalism.” I broadly agree, but add that it is exacerbated by Australia’s institutional arrangements that were undermined by the Howard government. This points to issues with cronyism, which is omnipresent in every economic system thanks to human nature. This is not to say there is no hope or that there isn’t a better way.

Further, much of the disparity relative to GDP-per-hour-worked appears to be a function of the booming mining sector, where Australia’s taxation regime has, in my view, missed the mark (and by a long way). Changing those arrangements will be difficult and see the usual rent-seekers distort the debate.

Unfortunately, it will be a very short-term win for low-income workers.

The FMW increase will be the excuse the RBA Governor and Board were looking for to increase interest rates. It will also be used as justification by the top end of town to increase prices or hold their hands out for more corporate welfare, or to import cheap labour.