Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian labour market – shows moderate improvement

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released of the latest labour force data today (November 17, 2022) – Labour Force, Australia – for October 2022. The labour market improveds somewhat in October 2022 with employment rising by 32,200 (0.2 per cent) on the back of strong full-time employment growth. With the sluggish labour force growth (as a result of below-average growth in the working age population) and an unchanged participation rate, the jobs growth saw unemployment and the official unemployment rate both decline. The full-time jobs growth also reduced underemployment. However, the underlying (‘What-if’) unemployment rate is closer to 6.1 per cent rather than the official rate of 3.4 per cent. There are still 1313.8 thousand Australian workers without work in one way or another (officially unemployed or underemployed). The only reason the unemployment rate is so low is because the underlying population growth remains low after the border closures over the last two years. But that is changing as immigration increases.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for October 2022 are:

- Employment increased by 32,200 (0.2 per cent) – full-time employment increased by 47,100 and part-time employment fell by 14,900.

- Unemployment fell by 20,600 to 477,600 persons.

- The official unemployment rate fell by 0.1 point to 3.4 per cent.

- The participation rate was unchanged at 66.5 per cent.

- The employment-population ratio rose 0.1 point to 64.3 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours rose by 43 million hours (2.3 per cent).

- Underemployment was fell by 0.1 point to 5.9 per cent (a modest fall of 10.1 thousand). Overall there are 836.2 thousand underemployed workers. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) fell 0.2 points 9.3 per cent. There were a total of 1313.8 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

In its – Media Release – the ABS noted that:

With employment increasing by around 32,000 people, and the number of unemployed decreasing by 21,000 people, the unemployment rate fell by 0.1 percentage point to 3.4 per cent …

The participation rate was 0.2 percentage points below the record high of 66.7 per cent in June 2022, but 0.7 percentage points higher than before the pandemic …

While the number of people working fewer hours due to sickness was around a third higher than we’d usually see in October, it was no longer two-to-three times higher, as it was earlier in 2022. October was the first month in 2022 where the number of people was less than half a million (467,000).

Conclusion: moderate employment growth with no change in participation was strong enough to net employment growth has fallen considerably, which may be the harbinger of worse to come as the impact of the rising interest rates and government cutbacks start to interact.

Employment increased by 32,200 (0.2 per cent) in October 2022

1. Full-time employment increased by 47,100 and part-time employment decreased by 14,900.

2. The employment-population ratio rose 0.1 point to 64.3 per cent.

3. Employment in Australia is 624.2 thousand (net) jobs (4.8 per cent) above the pre-pandemic level in February 2020.

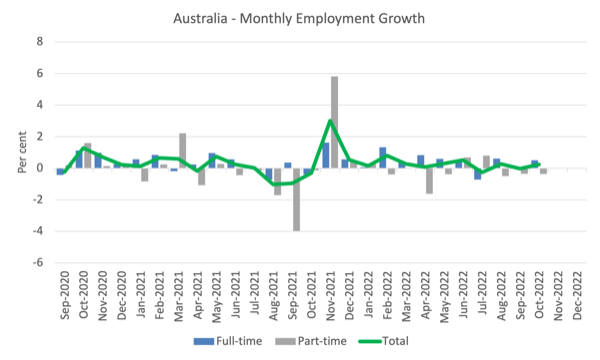

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to October 2022 using seasonally adjusted data.

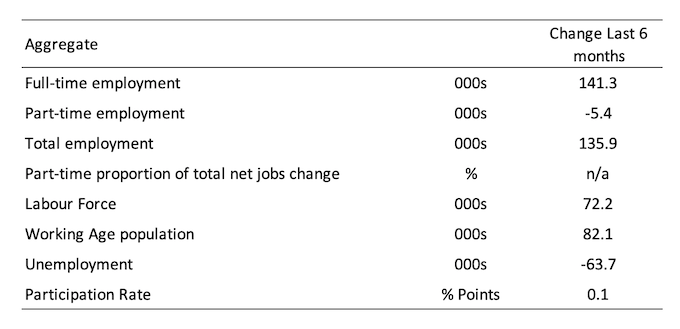

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months to provide a longer perspective that cuts through the monthly variability and provides a better assessment of the trends.

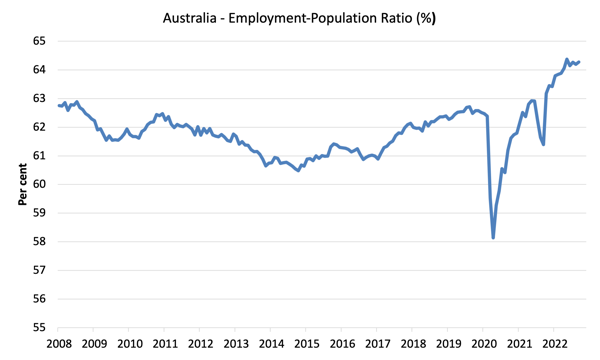

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since April 2008 (that is, since the GFC).

The ratio ratio rose 0.1 point to 64.3 per cent in October 2022 – showing an improving situation.

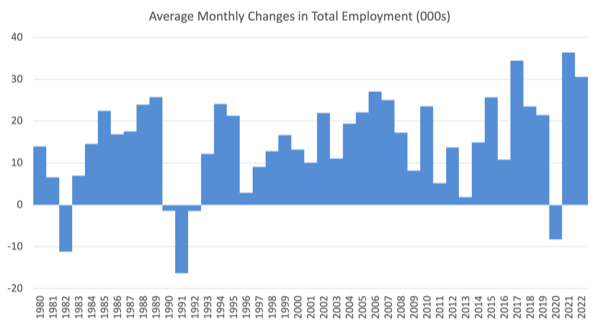

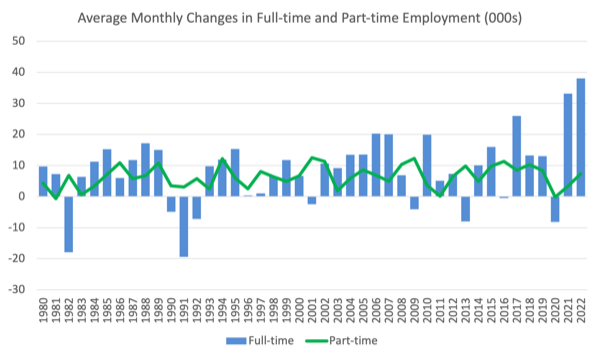

For perspective, the following graph shows the average monthly employment change for the calendar years from 1980 to 2022 (to date).

1. The average employment change over 2020 was -8.4 thousand which rose to 36.4 thousand in 2021 as the lockdowns eased.

3. So far in 2022, the average monthly change is 30.6 thousand.

The following graph shows the average monthly changes in Full-time and Part-time employment (lower panel) in thousands since 1980.

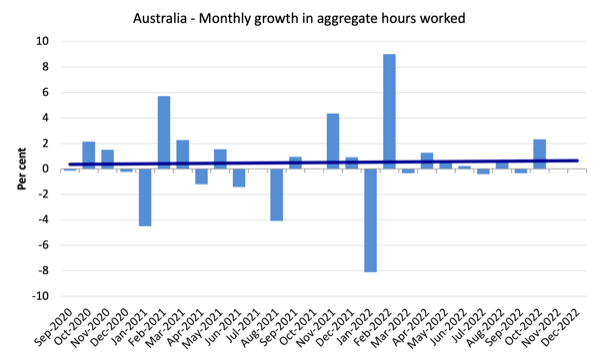

Hours worked increased by 43.2 million hours (2.3 per cent) in October 2022

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months.

The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change (skewed by the couple of outlier results).

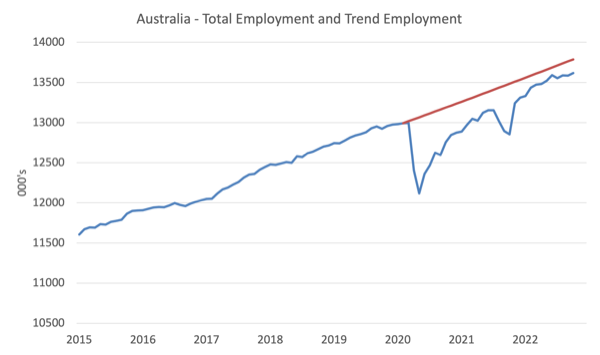

Actual and Trend Employment

The Australian labour market is now larger than it was in February 2020. But it is still some way from where it would have been if it had have continued to expand at the previous trend.

The following graph shows total employment (blue line) and what employment would have been if it had continued to grow according to the average growth rate between 2015 and April 2020.

In October 2022, the gap fell by 6.7 thousand to 169.7 thousand jobs as a result of the employment slowdown.

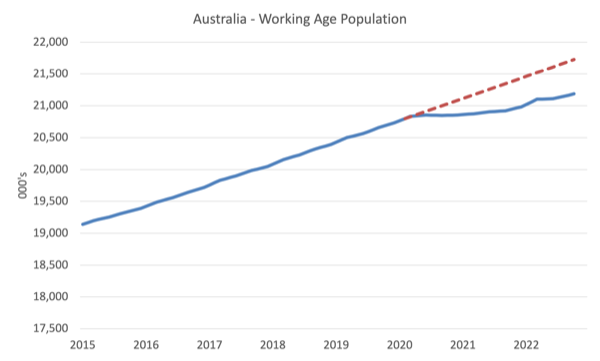

The Population Slowdown – the ‘What-if’ unemployment analysis

The following graph shows Australia’s working age population (Over 15 year olds) from January 2015 to October 2022. The dotted line is the projected growth had the pre-pandemic trend continued.

The difference between the lines is the decline in the working age population that followed the Covid restrictions on immigration.

The civilian population is 540.5 thousand less in October 2022 than it would have been had pre-Covid trends continued.

That gap rose in October 2022.

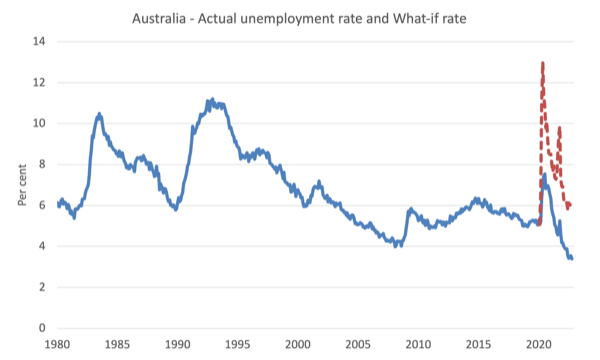

The following graph shows the evolution of the actual unemployment rate since January 1980 to October 2022 and the dotted line is the ‘What-if’ rate, which is calculated by assuming the most recent peak participation rate (recorded at June 2022 = 66.7 per cent), the extrapolated working age population (based on growth rate between 2015 and February 2020) and the actual employment since February 2020.

It shows what the unemployment rate would have been given the actual employment growth had the working age population trajectory followed the past trends.

In this blog post – External border closures in Australia reduced the unemployment rate by around 2.7 points (April 28, 2022), I provided detailed analysis of how I calculated the ‘What-if’ unemployment rate.

So instead of an unemployment rate of 3.4 per cent, the rate would have been 6.1 per cent in October 2022, given the employment performance since the pandemic.

This finding puts a rather different slant to what has been happening since the onset of the pandemic.

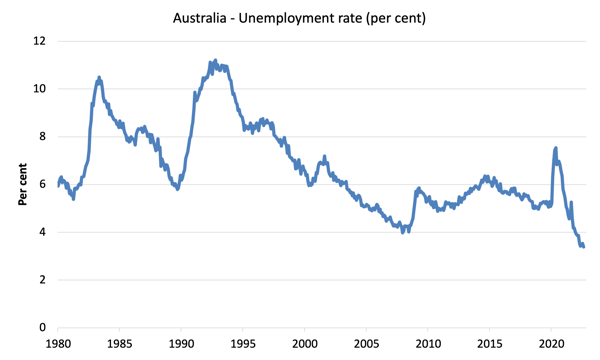

Unemployment fell 20.6 thousand to 477,600 persons in October 2022

Unemployment fell because the net rise in employment (32.2 thousand) outstripped the rise in the labour force (11.7 thousand).

With the participation rate constant, this signals an improving situation.

The labour force growth is still low however, reflecting the underlying slow growth in the working age population as a result of sluggish in-migration after a long period of border closures.

Also so bear in mind the ‘What-if’ analysis above and see the impact of the fall in participation below.

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from April 1980 to October 2022. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

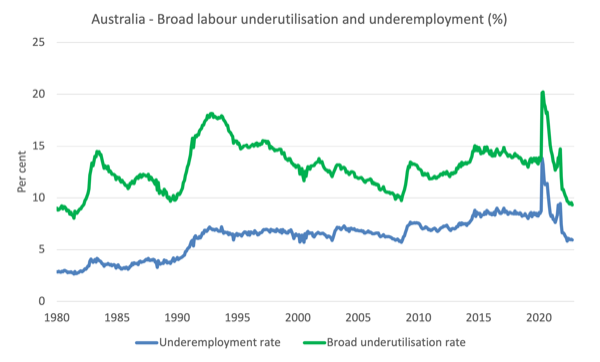

Broad labour underutilisation fell 0.2 points 9.3 per cent in October 2022

1. Underemployment was fell by 0.1 point to 5.9 per cent (a modest fall of 10.1 thousand).

2. Overall there are 836.2 thousand underemployed workers.

3. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) fell 0.2 points 9.3 per cent.

4. There were a total of 1313.8 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

The following graph plots the seasonally-adjusted underemployment rate in Australia from April 1980 to the October 2022 (blue line) and the broad underutilisation rate over the same period (green line).

The difference between the two lines is the unemployment rate.

The three cyclical peaks correspond to the 1982, 1991 recessions and the more recent downturn.

The other difference between now and the two earlier cycles is that the recovery triggered by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 did not persist and as soon as the ‘fiscal surplus’ fetish kicked in in 2012, things went backwards very quickly.

The two earlier peaks were sharp but steadily declined. The last peak fell away on the back of the stimulus but turned again when the stimulus was withdrawn.

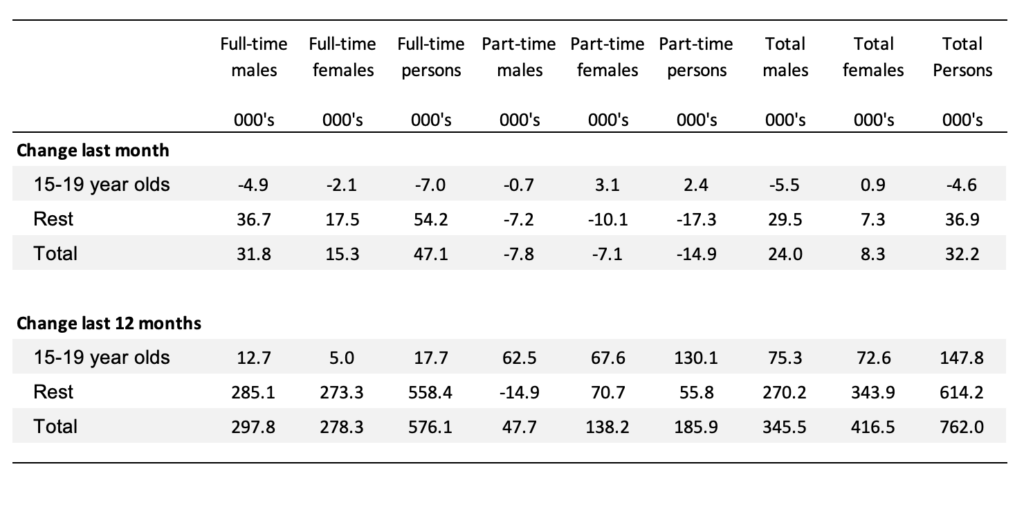

Teenage labour market deteriorated in October 2022

Despite the overall rise in full-time employment, teenagers lost 7 thousand net full-time jobs in October.

The part-time offset was on 2.4 thousand jobs.

The following Table shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month and the last 12 months by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest).

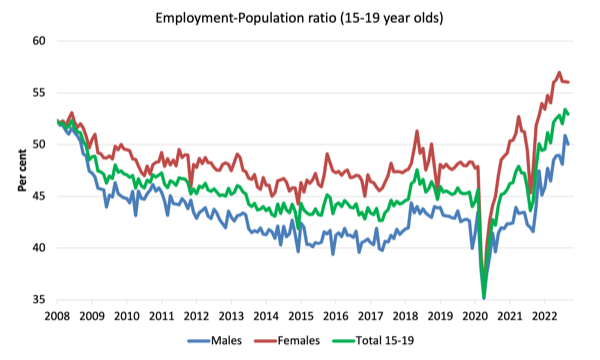

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context (relative to their size in the population) the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since June 2008.

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort.

1. The male ratio fell by 0.9 points over the month.

2. The female ratio was unchanged in October.

3. The overall teenage employment-population ratio fell by 0.5 points over the month.

4. Female teenagers have been doing better in relative terms than male teenagers.

Conclusion

My standard monthly warning: we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

My overall assessment is:

1. The labour market improved in October 2022 on the back of moderate employment growth (concentrated in full-time jobs) and a sluggish labour force growth.

2. With the participation rate constant, unemployment fell and the concentration of full-time job gains also reduced underemployment.

3. The underlying (‘What-if’) unemployment rate is closer to 6.1 per cent rather than the official rate of 3.4 per cent.

4. There are still 1313.8 thousand Australian workers without work in one way or another (officially unemployed or underemployed).

5. The only reason the unemployment rate is so low given the relatively tepid employment growth is because the underlying population growth remains low after the border closures over the last two years. But that is changing as immigration increases.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Anything We Can Do, We Can Afford

John Maynard Keynes, in a 1942 BBC address

https://jwmason.org/slackwire/keynes-quote-of-day-2/

“Anything we can actually do, we can afford.

***

With a big programme carried out at a regulated pace we can hope to keep employment good for many years to come. We shall, in fact, have built our New Jerusalem out of the labour which in our former vain folly we were keeping unused and unhappy in enforced idleness.”

Why do we need to rely on surveys when we can source the data directly from Centrelink?