Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

The Australian government ignores the cost-of-living crisis impoverishing vulnerable citizens

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period. He indicated that he would like to contribute occasionally and that provides some diversity of voice although the focus remains on advancing our understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its applications. Today he is going to talk about the current concerns about the cost-of-living crisis in Australia. Anyway, over to Scott …

The government does not care about the most vulnerable when it comes to cost-of-living

Over the past few weeks, Australians have been bombarded with messages from the Australian federal treasurer about how he (and the government) would be helping with cost-of-living pressures.

Much of the messaging was about how the government’s fiscal statement (aka the budget) would introduce responsible measures aimed at helping struggling families.

This was an important moment for the relatively newly minted (May 2022) Australian Federal Labor government.

It was their chance to show that all the talk leading up to the election and in the period since was more than just hot air.

If there was a report card, they would have got an F for a lot of things.

It is fair and very responsible for the government to help out people suffering as prices of everyday items and services have in some cases skyrocketed.

Unfortunately, despite the rhetoric, the government’s measures announced in the fiscal statement did very little to help those most in need.

Bill gave his assessment of the government’s announcements in his blog post – Australia’s latest fiscal statement from the government – a gutless document really (October 26, 2022) – noting that among other things the government’s plans offered

No real solution to the cost of living crisis for low-income families – who the government is content to see have their real wages cut while maintaining huge tax cuts for the highest-income earners and other assistance for high-income earners, which it inherited from the conservative government

It is easy to get tied up in all the noise around the cost-of-living crisis.

There is no doubt that for many Australians the cost of living has skyrocketed over the past year or so.

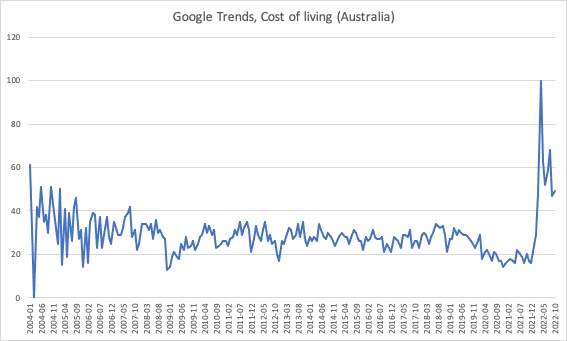

A quick search on Twitter while I was writing this showed that there were over 700 tweets in the past hour on the cost of living and eyeballing google trends data in the figure below shows a rapid increase in searches around the topic.

For context the numbers from – Google Trends

… represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not enough data for this term.

The cost-of-living crisis is not new

The problem is that for so many people, cost-of-living pressures were a daily occurrence even before inflation began to rise.

There are lots of data and stories about how the most vulnerable of our population suffer cost pressures every day in an attempt to simply survive, even in ‘normal’ times.

Anecdotally, on a recent trip to my local supermarket, I met an elderly woman who was standing in front of a selection of jams and spreads (Jelly for US readers).

I was buying strawberry jam for my sandwiches on my long weekend training rides. She was lamenting the fact that whilst she really liked marmalade, she couldn’t justify buying a jar, even the cheapest plain package variety.

She wandered off with her few items in her trolley, but no marmalade.

(As a side note, I followed her to the checkout and bought her a nice gourmet jar. She was thrilled).

This poor women’s marmalade woes were only the tip of the iceberg. We hear time and time again about people living on income support or those classified as working poor struggling with daily essentials.

The truth is that for those living in poverty, issues with the cost of living were a thing way before the term became a common conversation around the dining table.

Stories like this have been a common feature when social support agencies begin lobbying for a better deal for the most vulnerable citizens.

Scrolling through the Home Page of the – Australian Council of Social Services (ACOSS) – we read about a young Australian who:

… was homeless at 15. Youth Allowance meant that I didn’t starve to death, but it did mean that on top of the challenge of finishing high school while essentially couch surfing and moving 11 times in my senior years, I was hungry. I didn’t get any help to manage the allowance I received and I would often run out of food well before my next payment and drink water to try and fill up enough just to get to sleep. It also meant that I entered adulthood with a terrible credit history, as the allowance I had didn’t stretch to cover electricity, rent and other bills. I spent hours each month in distressing phone calls begging for extensions from power companies etc. It just didn’t stretch that far. It was time I could have been studying like my peers and doing better at school and university.

Beyond the stories, there are plenty of quantitative facts.

Recently I have been wading through survey data released as part of the – Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (HILDA).

The Survey is similar to the – Panel Study of Income Dynamics – in the United States and the – British Household Panel Study i- n the United Kingdom.

It is a valuable data source for investigating a range of important social and economic issues impacting Australians.

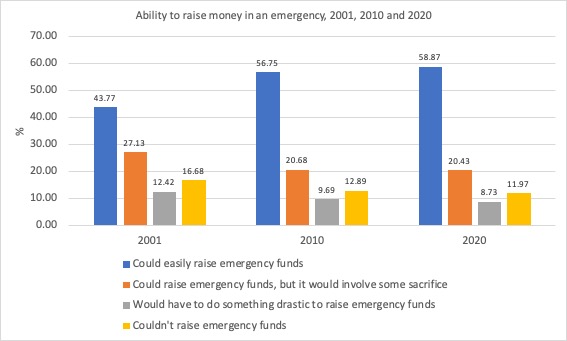

Since the survey began in 2001, people have been asked a question regarding their financial security.

Specifically, they are asked

Suppose you had only one week to raise $2000 for an emergency. Which of the following best describes how hard it would be for you to get that money?

Respondents were given four possible answers to choose from:

- Could easily raise emergency funds

- Could raise emergency funds, but it would involve some sacrifices

- Would have to do something drastic to raise emergency funds

- Couldn’t raise emergency funds

Perusing the raw findings, we learn that although the majority of respondents thought they could easily raise emergency funds, there were still many who thought they would struggle – either do something drastic or would not be able to raise the money.

The following graph captures this response:

In 2001, the first year of the survey, almost 30 per cent of respondents stated that they would either have to do something drastic or would not be able to raise emergency funds.

By 2020, the most recently available wave, the percentage had fallen but a fifth of respondents still reported difficulties.

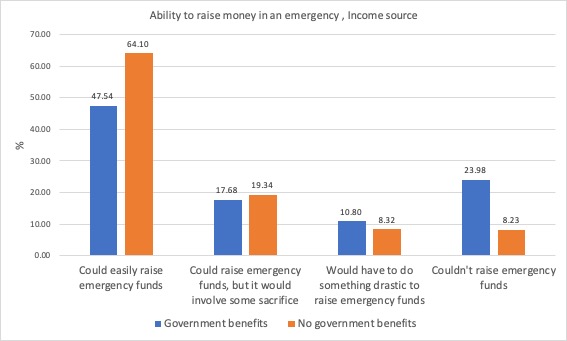

Moreover, we can dig a little more and discover that, not surprisingly, it is those reliant on government support who are hit the hardest.

Nearly a quarter of respondents receiving some form of government benefit said that they would not be able to raise money in an emergency.

The HILDA survey also contains a range of questions about material deprivation.

From the 2018 data (before the current crisis), we learn that

- While a small proportion (1.4%) of the sample said they couldn’t access medical treatment when needed, the majority of these respondents (72%) said the reason they couldn’t access medical treatment was because of cost;

- 7 % of the respondents said they forgo dental treatment. The overwhelming reason (83.9 %) for this group was again cost;

- A small proportion (1.1 per cent) said they were unable to keep their home warm during winter. Again, the cost was the reason given by the majority (53.8 per cent).

The following graph captures this response:

So, it is clear that for many people the cost-of-living crisis is not a new thing.

It has been a feature of their lived experience for some time.

Does the government really care?

Given this context, it is worthwhile reflecting on the current discussions around the cost-of-living crisis, and the ability or inability of the government to take action.

One thing is clear.

The current focus on the cost-of-living pressures that are impacting a wide range of individuals and households has thrust the issue into focus for those in power.

This should be a good thing.

But it also raises the question of why doesn’t the government seem to care enough about poverty in “normal” times.

In thinking about this I happened upon this commentary – Why is poverty not a priority for Australia’s major political parties (May 4, 2022) – written by Philip Mendes from Monash University.

This is a useful piece of writing that reminds us that the current level of concern is framed firmly through a neoliberal lens.

Commenting on a 2019 government inquiry into poverty Mendes points out that

… the neoliberal preference for placing the responsibility for resolving disadvantage on those living in poverty rather than society more generally underpinned the 2019 House of Representatives inquiry …

The report used the term “intergenerational welfare dependence” which Mendes argues

… frames poverty as a form of psychological illness or addiction, rather than the result of inequitable social and economic structures.

Typical neo-liberal stuff.

Blame the victim.

Tell them to lift their game.

Stop depending on hand-outs.

Work harder. Etc.

We might have expected this from the previous mean-spirited coalition-led government, but the lack of real action by the current Labor government is appalling.

For the current government, the missed opportunity to provide any sustained support for the most vulnerable represents a failure to grasp what is going on or understand how the most vulnerable in our society struggle on a daily basis.

This is most clearly illustrated in the kind of comments made by those currently in power. In a range of media reports, for example, the Prime Minister has time and time again argued that (Source):

… short-term rebates and cash injections would hurt Australians in the long run with rising interest rates and inflation.

This is rubbish and reflects a lack of understanding.

Talking up promises of cost-of-living relief makes for good media sound bites.

There is currently a senate inquiry into poverty which is due to be released in 2023.

Given the history of these kinds of inquiries, we will hear a lot of political talk about those living in poverty, but I would bet there will be any real action given the current attitudes expressed by the major parties.

Talking about responsible approaches and holding inquiries or other talk fests are not going to solve the problems our most vulnerable face with day-to-day living.

In the long term, ensuring secure well-paid employment, adequate training opportunities and well-funded public services, the kinds of things that governments seem to have jettisoned in the past, will help those living in poverty.

A more immediate response has to be the provision of financial support for our lowest-income earners to help as prices rise.

Despite the government bleating about how irresponsible short-term rebates or cash injections would be, we know this can be done.

We saw during the height of the initial COVID-19 wave governments provide supplements to low-income earners without any hand-wringing about where the money would come from or how it is fiscally irresponsible.

And we know that it makes a difference.

Evidence such as that presented by the ACOSS (Source) – in their March 2022 report shows that the introduction of supplement payments during the COVID -19 pandemic made a significant difference to the lives of those who were struggling to make ends meet.

Some of the key findings in this report were:

In 2020, income inequality and poverty declined during the ‘Alpha’ wave of the pandemic despite the deepest recession in a century and an ‘effective unemployment rate’ reaching 17%, due to robust public income supports – JobKeeper Payment and Coronavirus Supplement …

In the first half of 2021, employment and earnings recovered but these income supports were withdrawn. The available evidence indicates that income inequality and poverty increased above pre-pandemic levels.

A similar picture was painted in a Guardian article (December 29, 2021) – The Covid supplement lifted me out of poverty. Then it was cut and my life went back to the way it was.

The headline tells the story.

Conclusion

It is clear that our most vulnerable, those who are only just surviving or worse on low incomes, deserve the government’s attention more than ever.

Instead of talking up how responsible they are being, the current government should immediately introduce fiscal support to help the most vulnerable in society.

It is not going to make things harder for Australians, but rather, it is going to improve the lives of many.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Those of us who know and understand how the fiat currency money thing works continue to play by our opponents’ rules in using the language of the neoliberal capitalists and their neoclassical economics handmaidens. We allow them to set the words of and consequent mind’s eye images which are so ingrained in the understandings of the laity. If we can change the thinking from that of the falsehood of the scarcity of money to that of the reality of limited resources as being the basis for our economics and ultimate existence on this planet, perhaps there’ll be a glimmer of hope (a very dangerous feeling).

So much of the preachings of the orthodoxy has this economics/money stuff the wrong way around because it comes at it from a theoretical artificial and non-empirical (anti-science) basis. We won’t survive in that artificial reality by pursuing more of the same as we all appreciate. But how to turn it around without resorting to pitchforks in the street?

Both major parties are imbued with the neoliberal, money scarcity way of the world. It’s as if the ALP is operating to run interference for the LNP as they both serve the same capitalist donor class against the majority. The continuities in ideology as the baton was handed over at the 21 May election are there for all to see. The similarities with the Dems and GOP in the US and the Labour Party and the Tories in the UK couldn’t be clearer.

Poverty exists solely because there is a lack of money in possession of a repressed precariat who are widely touted to the citizenry, by those in power, that it’s all their own fault.

Labours fearing of the wrath of God i.e. spending is inflation, has been infused with their spirit so as to ensure that they follow the guided path clinging to the commandments i.e. economic dogma, that powerfully reinforce their faith in God; the RBA seen as an arc angel i.e. inflation saviour.

The lower classes deemed to be unholy in their pursuit for seeking the light i.e. knowledge of freedom, are taught ignorance to delay their elevation. They are required to be sacrifices by the prophets of power, if not already servants for the righteous.

Unless a crisis, the lower classes are cyclically doomed by the combined complacency. They are continuously entangled in a heavenly, chaotic, bind that fools them in to believing that less pressure is freedom – conditioned to suppress their will to fight. They know they are being demonised – but they lack the spiritual bond to protect thy neighbour.

Their saviours are the seekers of truth…