Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Australia’s latest fiscal statement from the government – a gutless document really

I don’t really want to write this post today given the hysteria that has appeared in the media over the last week. But it is an important event so I better. Working in Kyoto for the last month has given me a sort of sense of dislocation from the day to day macroeconomic debate in Australia. I still read all the information and study the data but being somewhat distant from it – and not watching any current affairs or listening to the radio – provides for calm. Anyway, last night (October 25, 2022), the new Federal Treasurer released the annual ‘fiscal statement’ (aka ‘The Budget’), after telling the nation since he was elected that the sky was about to fall in because the previous government had left a ‘trillion dollars worth of debt’. The new Labor government is so intent on looking ‘responsible’ and the exemplars of ‘sound finance’ that the population has been subjected to a daily briefing from the Treasurer and the Finance Minister that amounts to little more than nauseating lies. And last night’s fiscal statement? A joke really. It neither does what the Treasurer claims nor does it deal with the numerous policy challenges that face the nation in any significant way. The fiscal statement essentially fails to meet the challenges that are before us and will worsen over the next few years. A gutless document really.

Hard to cope with the commentary

I have been commenting on these things for many years now and it is getting harder each year.

Why?

Because just as a new cycle of predictions from the mainstream economists and their parrots in the mainstream press are disproven, a new sequence of predictions, usually totally unrelated to anything that is real, surface.

I had hoped that humanity was smarter than that and could see through all this self-serving (for wealthy vested interests) nonsense.

The day after the Treasurer delivered the fiscal data, the senior correspondent at the national public broadcaster wrote this:

The new treasurer’s post-budget speech was littered with references to new beginnings. But the numbers he presented harked back to another AC/DC hit from an earlier era: Highway to Hell.

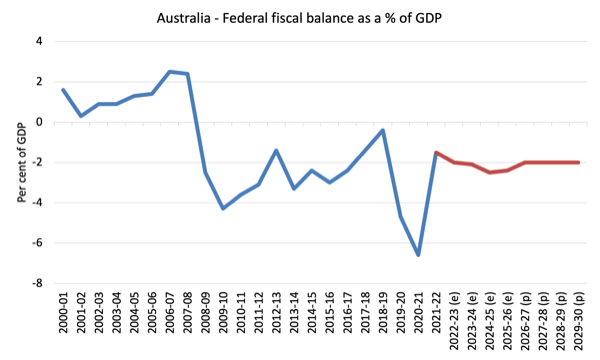

It was followed by a graphic entitled “We’ll take the low road”, which didn’t depict Australia’s very low unemployment rate at present, but the fact that the fiscal deficit is forecast/projected to remain around 2 per cent of GDP for the next decade.

This was called a “brutal forecast” and a terror laden conclusion that “Australia’s budget will never return to surplus”.

The chance of a surplus has been “blown out of the water” by: (a) the decision taken several years ago by a previous government to spend more on making the lives of those with severe disabilities somewhat more enjoyable and manageable; and (b) “the extraordinary lift in global interest rates that has drastically escalated the cost of supporting our debt.”

We should celebrate (a) and deplore the gross exageration and irrelevancy of (b).

This is what was so hellish to this commentator (and most others for that matter). The red segment is a combination of forward estimates provided by Treasury and a continuation of the last forward estimate.

First, these projections are largely irrelevant because there is no way the government or anyone else knows what is going to happen over the next 10 years.

The general principle is that the fiscal balance should not be a target of policy because the government cannot control its final outcome in any one year.

They thought the deficit would have been higher this year just gone but better than expected labour market outcomes reduced the size significantly.

What governments should target is well-being – which is why we should celebrate the improved funding to disability support services.

There is nothing hellish about the fact that the deficit might remain at 2 per cent forever (for that matter).

The only things that matter in this context is whether the fiscal action is translating in real outcomes – like reducing the unemployment and underemployment rate – in the context of what is happening in the external and private domestic sectors.

I will return to that point later.

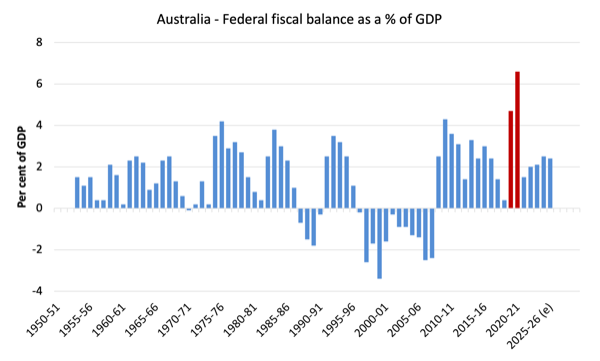

But consider this graph which provides an historical perspective. I have also expressed the fiscal balances as positive numbers (as a percent of GDP) because they add to net financial assets in the non-government sector and stimulate private income and wealth.

They are a positive injection.

The surpluses, that marked the shift to neoliberalism prior to a sequence of crises that pushed the fiscal balance back into its usual state of deficit, are shown as negative numbers.

Why?

Because they undermine economic activity in general and the liquidity squeeze on the non-government sector arising from the government putting in less than it is taking out, forces the non-government sector to liquidate some wealth holdings in order to bridge the gap (its deficit).

The point is that over this 69-year period from 1953-54 to 2021-22, the federal government has been in deficit 81 per cent of the time.

And when it has recorded surpluses, the Australian economy has entered recession soon afterwards.

Not much change in total but a lot of opportunities missed

While the dominant talk from the government and the media has been the need for ‘budget repair’, a ridiculous concept if there ever was one (cars need repair from time to time), the fiscal statement released last night by the Treasurer essentially held the fort.

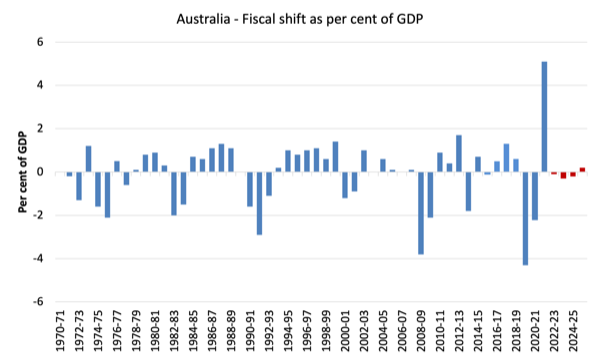

The fiscal shift from one year to another is the change in the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP changes. It is the result of two factors – the fiscal balance itself (in $As) and the value of nominal GDP (in $As).

The following graph shows the recent history (from 1970-71) of fiscal shifts up to the end of the projection period (2025-26).

I have coloured the current fiscal year (2021-22) blue and the remaining red columns are the forward estimates for next year (2022-23) and those beyond.

The government is projecting a -0.1 per cent of GDP increase in the deficit in the coming year and then very small expansions over the next two years followed by a small contraction in 2025-26.

So for all the bully boy tough talk from the Treasurer about dealing with the ‘fiscal cliff’ he didn’t have the courage to implement a fiscal shift to match the rhetoric.

For which the Australian workers should feel somewhat relieved.

But, given the circumstances, there is a real need to increase the size of the deficit in the coming year at least.

The government has relented on doing anything significant to help low income workers and their families deal with the current cost of living crisis, which will get worse, given the state of the floods across the east coast farming areas.

They also failed to help certain sectors which have been ravaged by Covid and the failure of the previous government to support those sectors.

I am thinking of the arts sector here but we could extend the net to casual workers in general.

And there is very little expenditure earmarked to deal with climate change – or even a coherent plan to deal with it outlined by the government.

The urgency of that problem should have required significant fiscal action after the new Labor government inherited the office following more than a decade of non-action from the previous climate-denialist conservatives.

Where is the growth coming from?

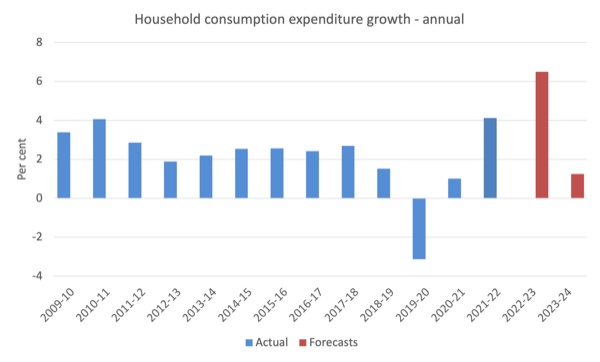

The 2022-23 fiscal statements forecasts that real household consumption expenditure will grow by 6.5 per cent in 2022-23 and 1.5 per cent in 2023-24.

The following graph shows the annual Household consumption expenditure growth from 2009-10 to 2023-24, with the red bars capturing the Government’s projections.

You can see that the forward estimates are very optimistic based on what is likely to happen in 2022-23, despite whole sections of the statement being devoted to the major global slowdown and threat of recession.

They clearly think that the global slowdown will hit mostly in the 2023-24.

That is optimistic given current trends.

Further, normally we would expect household expenditure growth of that magnitude to come from a very strong wages growth environment.

But wages growth has been at record low levels. To engineer the relative ‘huge’ jump in household consumption expenditure in 2022-23, the fiscal statement is projecting a massive jump in nominal wages growth.

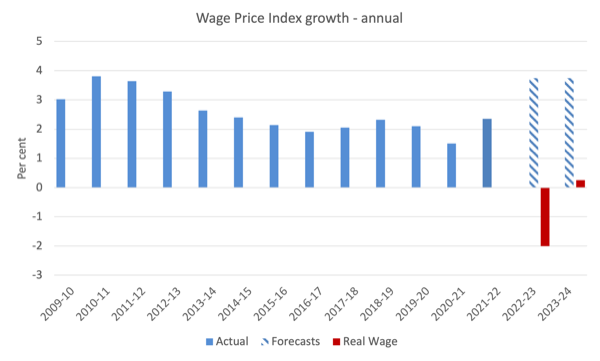

However, they are also projecting significant real wage cuts over the next two fiscal years as shown in the following graph.

Coupled with the fact that the CPI projections are probably an understatement given today’s CPI data (which I will analyse tomorrow) and that the forward estimates of nominal wages growth are far too optimistic – my conclusion is that the real wage cuts will be larger than even the government estimates.

Conclusion: The Government is wanting us to return to the unsustainable situation where private debt escalates to maintain household consumption expenditure while real wages growth remains negative.

Why the government strategy is unsustainable

The other observation is that pre-pandemic, households were already increasing their saving ratio and reducing their consumption expenditure growth as a result of the record levels of household debt they were carrying.

So while there has beeb a temporary spend-up by households as the pandemic has retreated (at least in the way people are thinking about it), I doubt that will last for very long and will be sufficient to deal with any global contraction and the unwillingness of the government to expand its fiscal support.

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector (S – I) equals the sum of the government financial balance (G – T) plus the current account balance (CAB).

The sectoral balances equation is:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector to net save overall (S – I > 0).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to accumulate financial assets.

Expression (1) can also be written as:

(2) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting.

The government is estimating that the negative global factors will push Australia’s terms of trade from the 12.2 per cent increase recorded in 2021-22 to a -2.25 per cent result in 2022-23 and a massive 20 per cent reduction in 2023-24.

In other words, the commodity price boom which has pushed the external balance into surplus recently is forecast to end and Australia will return to its usual position of a external deficit of around 3.5 to 4 per cent of GDP – a state that has been dominant since the 1970s.

This is the context I mentioned above and one cannot understand or make any meaningful assessment of the fiscal statement without taking it into account.

At the time of writing, I think I am the only commentator who is talking about the statement in these terms.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is not widely used as an assessment tool, to the disadvantage of the debate.

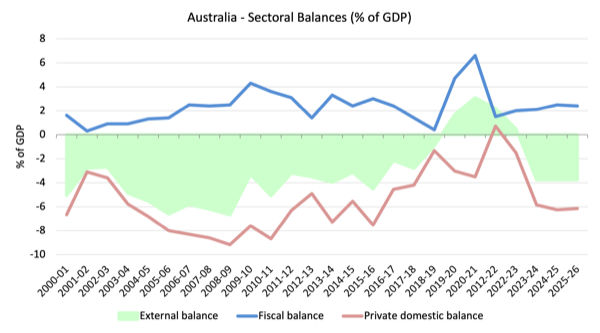

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2025-26, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in ‘Budget Paper No.1’.

The projections begin in 2022-23.

I have assumed that the external position in 2024-25 will be the same as the Government’s estimate for 2023-24.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

I have modelled the fiscal deficit as a negative number even though it amounts to a positive injection to the economy. You also get to see the mirror image relationship between it and the private balance more clearly this way.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) projected to return to a deficit of 3.75 per cent of GDP in 2023-24 (as a result of a sharp reversal in the terms of trade), the private domestic balance overall (solid red line) heads quickly into higher deficits as the projected government balance (blue line) stabilises around 2 per cent of GDP.

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit. This not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to start the process of rebalancing its precarious debt position.

That process was interrupted by the renewal of the fiscal surplus obsession in 2012-13.

You can see the red line moves into surplus or close to it and the private domestic deficit increases as a result of the liquidity squeeze.

The strong fiscal support during the pandemic overwhelmed all the nonsensical deficit scaremongering allowed the private domestic sector to increase its overall saving (and pay down debt) which was a good thing.

But as the previous government withdrew its stimulus, the private domestic sector has only one option given the trends in the external sector if it wants to maintain consumption expenditure – resume the process of accumulating more debt.

With a global recession threatening, the strategy outlined in yesterday’s fiscal statement is once again placing the economy on an unsustainable path relying on household debt accumulation, which is a finite process.

The scandals among many:

1. There were no significant allocations made to deal with climate change.

2. No substantial increases in foreign aid

3. No help for the arts sector.

4. No commitment of real wages growth in the public sector to lead the economy.

5. No real solution to the cost of living crisis for low-income families – who the government is content to see have their real wages cut while maintaining huge tax cuts for the highest income earners and other assistance for high income earners, which it inherited from the conservative government.

6. A fairly parlous response to the need for more social housing.

Conclusion

A pretty gutless effort really.

I didn’t want to write any of this.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Corporate media are there to intoxicate public opinion, to usher the vested interests of stockholders – who are capitalists and, therefore, need to protect their assets from “socialism”.

The funny thing about this is that public media went through the same path and became propaganda peddlers too.

Not only in Australia. It’s everywhere.

I wonder what forces could drive such a major breakthrough in the propaganda battle.

And there’s only one answer: $.

Lots of it.

That means that all lies and fairy tales arise from the same source: corruption.

Big time corruption.

The neoliberal obsession with so called sound finance is becoming increasingly untenable. But I am not at all confident that many people understand that.