In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Covid-specific inflationary pressures are dominant and are transitory

There has been some very interesting data and other research published recently that allow us to more fully understand what is driving the current inflationary pressures. There is a massive lobby now pushing the idea that the central bank bond-buying programs and the rising fiscal support during the pandemic are responsible. This sort of narrative is coming from the mainstream economists who are suffering attention-deficit disorders (even though they get the top platforms all the time to preach their views), and, who in the last few weeks have become increasingly vehement and personal in their attacks on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Their actions are a sign that the cognitive dissonance is getting to them and they realise they have been left behind. But the evidence that is continually coming out across a number of indicators continues to reaffirm my view that the current inflationary spikes are being driven by the total abnormal circumstances the world has found itself in as a result of the pandemic. The usual institutional and structural drivers of an inflation – which were certainly prominent in the 1970s – seem to be absent at present. I will present further research next week on this topic as I build further evidence.

ECB admit interest rates rises do not work

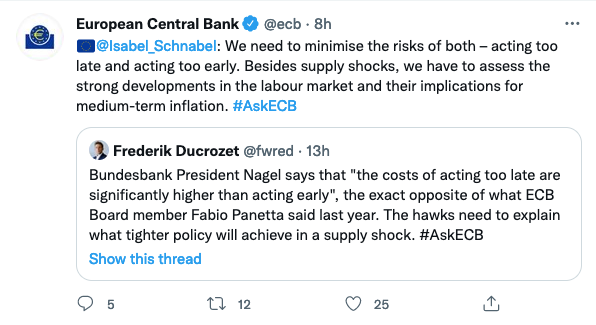

The ECB conducted a Twitter Q&A yesterday (February 10, 2022) with Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel answering the questions.

Several answers were telling.

1. “Inflation has risen mainly due to energy prices which we cannot affect directly. But we are seeing that inflationary pressures are broadening and becoming more persistent. Policy optionality is therefore more important than ever.”

2. “If there is a risk that inflation expectations become unanchored, we need to take action even if the shock is exogenous. Currently, longer-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored.”

3. “Due to lags in policy transmission “transitory” shocks typically do not require policy action. They matter for monetary policy when there is a risk that they become entrenched in expectations, requiring policy action to protect price stability.”

4. There was this interesting exchange:

5. “ECB simulations show that the stock of assets acquired under APP and PEPP will put sizeable downward pressure on interest rates across the maturity spectrum for the years to come.”

6. “In the 1970s rising oil prices triggered a harmful price-wage spiral, as inflation expectations drifted away. Today longer-term inflation expectations are well-anchored. We will ensure that high inflation does not become entrenched.”

7. “The empirical link between money growth and inflation has weakened over recent decades. Inflation developments depend on the transmission of policy measures to the real economy, which hinges, for example, on the state of the banking sector.”

8. “Raising rates would not lower energy prices. But if high current inflation threatens to lead to a de-anchoring of inflation expectations, we may still need to respond, as our mandate is to preserve price stability.”

9. “What matters for inflation is the growth in wages over and above productivity growth. We carefully monitor wage developments as they are crucial for the inflation outlook”.

So what you get from all that is effectively what I have been writing about for the last year when I discuss inflation.

Interest rate increases are not appropriate when OPEC is using its cartel power, or workers are sick from Covid and cannot deliver or produce goods and services, or lockdowns stop service purchases and boost goods purchases and the supply-side cannot respond quickly enough.

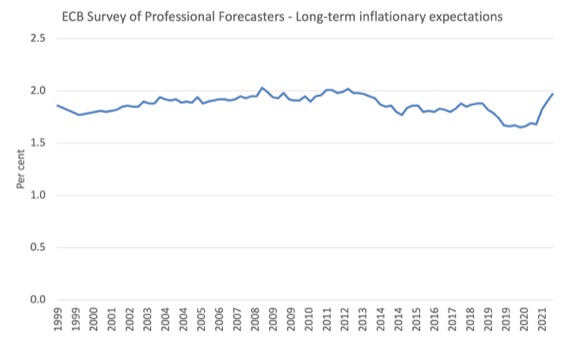

The following graph shows the long-term inflationary expectations from the – ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters First quarter of 2022.

The long term inflationary expectations (for 2026) have risen over the course of the pandemic but are still below 2 per cent (1.97 per cent in January 2022).

There is no break-out evident.

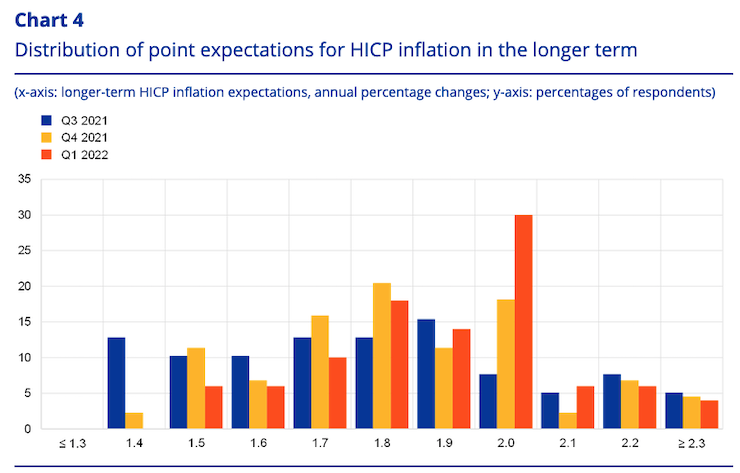

This graph (taken from Chart 4 of the ECB SPF) reinforces that conclusion. It shows the distribution of the point estimates of inflation across the survey group.

The concentration between 1.8 per cent and 2.0 with a shift towards 2 over the last 3 quarters tells me that this group is not forecasting an inflation outbreak over the next 4 years.

I can also note that the Euro 5-year, 5-year inflation swap rate has been declining recently, which also accords with what is happening in the US.

Speaking of which – here is the graph for the ‘5-year, 5-year forward inflation expectation rate’ in the US (daily data) which measures “expected inflation (on average) over the five-year period that begins five years from today”.

The data runs from January 2003 to yesterday, February 9, 2022.

The series most recent peak was on October 15, 2021 (2.41 per cent) and has been on a consistent downward trend as the nature of the current price pressures becomes more obvious.

I caution though.

In its July 2006 Monthly Bulletin article – Measures of Inflation Expectations in the Euro Area – the ECB noted that:

Inflation-linked swap quotations are an additional source of information about market participants’ inflation expectations … The resulting inflation-linked swap rates should, therefore, not be interpreted as direct market expectations of future inflation rates.

There is also mixed survey evidence.

So at least in Europe and the US, there is no breakout of inflationary expectations, which might drive the supply constraints into a generalised inflation.

So this part of the story looks to support the transitory, supply-side interpretation, I have been offering for more than a year now.

The labour market

The European Commission conducts regular – Business and consumer surveys – and one of the questions they ask business firms relate to “Factors limiting production”.

In their – January survey – they found:

Reports on shortage of material and/or equipment as a factor limiting production climbed to the highest quote on record (+3.6pp to 50.8% of all industry managers). These production constraints are compounded by shortage of labour force, with a record 25.9% (+2.4pp compared to October) of managers identifying labour shortages as a limiting factor for production …

Capacity utilisation in services decreased …

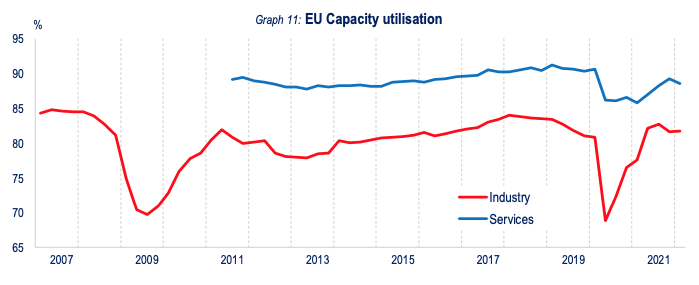

They produced this graph (Graph 11 EU Capacity Utilisation) which tells me that there is still excess productive capacity available across European firms – which, in turn, tells me that this is not a demand-driven price episode.

Further, I consulted the most recent data for ‘negotiated wage rates’ for the Euro area, which gives a good indication of wage pressures coming from organised labour bargaining.

Refer back to Isabel Schnabel’s answer (quote 9 above) about ‘what matters for inflation’.

Data is available from the Eurostat and the ECB (Source) from the March-quarter 1991 to the September-quarter 2021.

Here is a graph of the annual growth in negotiated wages.

To help you understand the implications, I repeat what I have often written.

If labour productivity growth is growing at say x per cent per annum (which reduces unit labour costs) then nominal (money) wages can grow by the same rate without putting any cost pressures on the rate of inflation.

Average labour productivity (output per hour) has been 2.2 per cent over the period March-quarter 1995 to September-quarter 2021. Over the 12 months to the September-quarter 2021 it averaged 4.5 per cent (Source).

So using the long-term average as a guide to discern the available inflation-free headroom for wages growth, and, given the ECB is targetting a 2 per cent inflation rate, then wages can grow at around 3 to 4 per cent per annum without there being any significant inflationary impacts.

The graph shows that not only is the rate of growth in negotiated wages falling, it is now down to 1.36 per cent, which means that not only are real wages falling (hardly a sign of a demand boom) but the gap between productivity growth and wages growth is rising.

Again, experts look at this data and conclude there is not a demand-side (overspending) dynamic driving the inflation trajectory.

The supply constraints

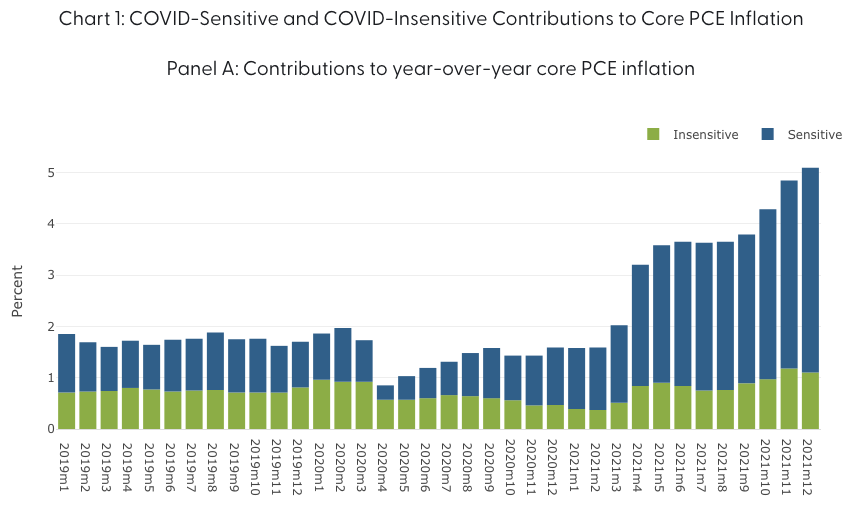

The San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank conducts very interest – Economic Research – and one of the current projects is to study the – Inflation Sensitivity to COVID-19.

They provide decompositions of the growth in US inflation (core personal consumption expenditure – PCE – measure) that can be traced:

… to the economic disruptions caused by the pandemic.

They write that the “PCE measure of U.S. inflation is considered particularly useful for identifying underlying inflation trends.”

It excludes the short-run volatility coming from “food and energy products”.

They calculate “sensitive and insensitive components”, where:

COVID-sensitive components include those categories where either prices or quantities moved in a statistically significant manner at the onset of the pandemic, between February and April 2020. COVID-insensitive components include all other core PCE categories.

They produced this really interesting graph (Chart 1 from the FRBSF research).

The interpretation is pretty clear.

Inflation is being driven by Covid-specific effects and when they are attentuated (if) then what is left is low and pretty stable inflation.

They also present a breakdown of the Covid sensitivity into demand and supply components, which I will write about another day when I have more time.

You can learn more about this research from:

Shapiro, A. (2020) A Simple Framework to Monitor Inflation, FRB San Francisco Working Paper 2020-29. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2020-29.

Conclusion

I am maintaining my view that the current inflationary spikes are being driven by the total abnormal circumstances the world has found itself in as a result of the pandemic.

The usual institutional and structural drivers of an inflation – which were certainly prominent in the 1970s – seem to be absent at present.

So the assessment – Transitory – remains.

And repeating, that doesn’t mean short-term. Transitory means as long as the special circumstances are present.

The risk is the longer it takes to resolve the pandemic, the more likely some of those institutional and structural forces might emerge. I doubt it though.

Our edX MOOC – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century continues

We are off and running again for another year with the first day of our MMTed/University of Newcastle MOOC – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century.

The course is free and will run for 4-weeks with new material each Wednesday for the duration.

It is not to late to enrol and became part of the already large class.

Learn about MMT properly with lots of videos, discussion, and more.

This year there will be some live interactive events offered to participants, which adds to the material presented previously.

So even if you completed the course last year, these live events might be a reason for doing it again.

Further Details:

https://edx.org/course/modern-monetary-theory-economics-for-the-21st-century

If you want to do the course, get in early as then you avoid having to catch up.

All are welcome.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m always drawn by Warren’s statement of the bleeding obvious in his book “Soft Currency Economics”.

“Little or no consideration has been given to the possibility that higher prices may simply be the market allocating resources and not inflation.”

Warren Mosler has said many interesting things but this statement, I would say, is a load of old cobblers.

It is relative prices that effect changes in resource allocation not changes in the general price level.

MMT does not say much about the velocity of circulation (VoC) of a fiat currency. The Bank of England never mentions it; yet, the US Federal Reserve routinely publishes it. The Treasury creates and spends new money every day into the non-government sector. The latter has got into the habit of saving that money and not spending it, so the Treasury can get its money back, via taxation. The Japanese are the poster kids for hoarding the government’s money.

For instance. have a look at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M1SL and https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2SL The US Treasury is fiscally stimulating like crazy. The budget deficit that creates, is not a problem MMT wise. But, there is a wall of the government’s monetary base (MB) plus liquid deposits in Commercial Banks (M1); out there, like a very big compressed spring that could go boing at any moment. You can see where it went wrong in 2008 https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?id=M2V,M1V,

Does velocity of circulation matter in the MMT framework? https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2014/september/what-does-money-velocity-tell-us-about-low-inflation-in-the-us

“It is relative prices that effect changes in resource allocation not changes in the general price level.”

The ‘general price level’ is just a collection of relative price changes. In other words ‘the general price level’ doesn’t really exist. It’s another of those aggregate figures that hides more than it reveals – as we can see when we drop down into the details.

There isn’t enough gas. The price is going up until the indifference level is met. Somebody has to have less gas than they want.

Rising interest rates to combat inflation means that we should be withnessing excess prodution of goods and we need to curb that excess activity, by making credit more expensive.

Well, that is far from happening.

In the first place, we (the western world, that is) are in a scenario of declining production of goods.

We turned into services to offset the waning industrial production of goods.

Could we say the services industries are over-heated?

There is no wage pressure on services, so no – it ain’t overheating.

But rising interest rates has another outcome: idle money can be applied in low risk finance instruments, paring the effect of inflation on idle money, which is corrosion.

And, guess who cares for the interests of the people with idle money?

There you have it.

Neil,

Say the price of apples is $10 and the price of oranges is $15. The relative price ratio of oranges to apples is 1.5.

If the general price level rises 20% then the price of apples becomes $12 and the price of oranges becomes $18. The relative price ratio remains unchanged at 1.5.

There was inflation of 20% but relative prices remain unchanged.

Yesterday, a bloke called Karl Smith wrote an op-ed in Bloomberg magazine, entitled “No this Isn’t Modern Monetary Theory’s Moment”.

He is presented as a former vice president for Federal Policy at the Tax Foundation and assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina.

In it, he wrote things like:

1) “The current state of the economy shows the consequences of unchecked government spending”.

2) “In effect, America was putting MMT into practice”

Which leaves me with two questions:

1) Where does MMT says anything about unchecked spending?

In all I read about MMT, I never found anything even close to “open season for profligacy of government’s spending”.

The money needs to be spent in things that can spur producitivity gains in the future, as the job guarantee, which he sees as profligate spending.

I see it as a future investment in the most fundamental resource of all – people.

So, bridges are falling apart in the US.

Bridges cut travelling time, cut transport costs, make the US more productive.

Someone in the past built those bridges, because they were necessary.

As much as we need now to build new bridges, to cut more travelling time or to replace the obsolete ones, before they fall apart and compel us to make hundreds of miles, to find the next bridge – if it didn’ fell apart either.

2) The US government never did throw away neoliberalism and assumed MMT as it’s new doctrine.

What they did was what had to be done.

So, they adhered to neoliberalism as a volunteer constraint and are willing to go back to it, as soon as the MMT laws are no longer mandatory to keep the neoliberal machine running.

When it comes (mister Smith thinks it’s about time), we can go back to our favorite sport of pumping money to the elites pockets – until the next crisis hits us in the head again.

Parroting neoliberal mumbo jumbo is a way to keep his job, as long as the neoliberal paradigm doesn’t crumble completely – which is a matter of time.

“If the general price level rises 20%”

Yes I know the myth, but that isn’t what happens in reality. In reality people have apples and offer them for sale. People have oranges and offer them for sale.

Then something happens that makes people go off oranges and suddenly the price of apples shoots up.

But inflation is still declared – even though all that has happened is oranges have gone out of fashion and the apple producers haven’t caught up yet.

There is no general price rise – as the decomposition figures show. Categories are all over the place.

“MMT does not say much about the velocity of circulation (VoC) of a fiat currency.”

What does taxation do?

If I spend £100 into the economy at a 1% transaction tax rate, how many hops before the £100 disappears in tax?

Now how many hops at 5% transaction tax rate?

Assume spending stops when you have less than £1.

Velocity control is baked into MMT at root via the taxation autostabiliser. Generally the faster things move, the more tax is generated which helps cool things back down.

The flow in and out of the saving stock is largely counterbalanced by changes in the size of the labour buffer stock (preferably a Job Guarantee).

It’s only when turbulence gets extreme (eg. the pandemic) that you have to knock it out of autopilot and switch to manual.

Neil,

“There is no general price rise – as the decomposition figures show. Categories are all over the place.”

I don’t think there would be an economist that would say uniform increases in prices occur across the board. They don’t. That is not to say that there are tendencies across the board for prices to increase owing to macroeconomic factors – inflation in other words.

“Then something happens that makes people go off oranges and suddenly the price of apples shoots up. ”

Yes, certainly these things happen but these effects are not related to macroeconomic tendencies. These effects are related to microeconomic factors, that is factors which affect only a narrow range of goods. An entirely different aspect. It is these factors which affect relative prices and the decisions economic agents (be they consumers or producers) make about specific goods. It is these factors which determine resource allocation.

Neil,

“There is no general price rise – as the decomposition figures show. Categories are all over the place.”

I don’t think there would be an economist that would say uniform increases in prices occur across the board. They don’t. That is not to say that there are tendencies across the board for prices to increase owing to macroeconomic factors – inflation in other words.

“Then something happens that makes people go off oranges and suddenly the price of apples shoots up. ”

Yes, certainly these things happen but these effects are not related to macroeconomic tendencies. These effects are related to microeconomic factors, that is factors which affect only a narrow range of goods. An entirely different aspect. It is these factors which affect relative prices and the decisions economic agents (be they consumers or producers) make about specific goods. It is these factors which determine resource allocation.

Being a non-economist I like to consider things by reverting back to first principles in an attempt to see how it might be working or not. A few thoughts.

Do we even have an inflation (a continuous increase in prices across the board) problem or is it a problem of current price increases due to particular/generalised supply restrictions providing an opportunity to gouge or apply pass through increases to maintain margins which are feeding price rises? Such price rises will likely conclude when normal supply levels return, I suggest. It may mean that an increased price due to those circumstances will become the new base for any future rises or prices will fall back to a lower base as a result of competition.

How does inflation commence? A business(es) puts its prices up. And then continues to increase its prices thereby satisfying the formal definition of inflation.

Why does a business increase its prices? (1) to maintain or increase its profitability (2) to gouge its clients because it can get away with it in the circumstances. A ready made opportunity for business to raise prices is during a supply side restriction of goods/services where demand is maintained while the supply shrinks.

It seems to me that it is only where there is effectively full employment that labour will have the potential power to demand wage increases to increase its share of business profits. As a result, business might raise its prices in an attempt to claw back its profitability. Such circumstance may or may not lead to continuous price increases following wage increases in a wages-price inflation spiral; depending upon what, if any, accommodation can be reached between labour and business/capital and/or via government intervention.

Which comes first? The chicken or the egg? Depends on the balance of power between labour and capital – full employment puts more negotiating power with labour; unemployment puts more negotiating power with capital. We have now been in a capital controlled NAIRU-centric western world at the increasing expense of labour for the last 40-50 years in this financialised neoliberal era. The pandemic may well be increasing labour power in selective areas where business typically relies on low cost labour and such labour is temporarily unavailable.

@acorn

I haven’t seen any mention of velocity of money in my readings of MMT.

I have seen it mentioned multiple times in other discussions, but as far as Joseph Wang is concerned it is a “zombie concept”. https://fedguy.com/zombie-concepts-velocity-of-money/

“Yes, certainly these things happen but these effects are not related to macroeconomic tendencies.”

They are. They are only not related to macroeconomic tendencies in mainstream thinking – which as we know here is utterly devoid of any intellectual value.

The macro is an emergent property of the micro. There are only people interacting with each other – no natural laws.

“It seems to me that it is only where there is effectively full employment that labour will have the potential power to demand wage increases to increase its share of business profits. As a result, business might raise its prices in an attempt to claw back its profitability.”

That thought frame is always where the mistake is made. It’s serial/category thinking rather than multiple/individual thinking.

There are many people, and there are many firms. All have plans. Many are disappointed with their lot, which means they are after somebody else’s lot. What that means is prices remain stable when everybody is scared to ask for more money in case they end up with nothing or less – because whoever they asked for more money from went elsewhere.

An individual’s job is under threat from somebody who sees that job and current wage as a promotion. A firm’s price is under threat from a competitor who improves their productivity and can quantity expand rather than price expand.

That’s the regulatory containment field we have to hold the capitalist reaction in, if we’re to get it to generate more out than we put in.

Sometimes you wonder if it is more difficult than creating fusion power.

@ Tony,

Having read your link, I think Joseph Wang has given a rather misleading title to his piece. He would better have called it “Zombie Concept: Velocity of money is fixed”. He says “If you assume that velocity is fixed in the short-run, then higher money supply would mechanically lead to a higher GDP. Sounds reasonable, but it is wrong.” My understanding is that adherents of MMT would agree with him.

Neil. If the non-government sector hoards the governments spending, it does not matter what the transaction tax rate is, the “spending multiplier” and “auto-stabilisers” won’t operate; the government sector just has to keep spending new money. Japan demonstrates that fact. UK tax revenue 32% of GDP; Japan 9.7%. UK gross savings 14% of GDP; Japan 30%.

For students of the old 2007 days. “In the second half of 2006, broad money growth rose to its highest level since 1990 and has remained high. Over the same period, interest rate spreads on household and corporate credit declined to unusually low levels. In recent months there has been considerable turbulence in financial markets – a process that is still under way. A key question is what developments in money and credit growth imply for the inflation.” (Shortly after it all went bang.)

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2007/interpreting-movements-in-broad-money.pdf

Also, even further back to 1994. “Given that MO is demand determined, explaining its behaviour is a matter of identifying the factors that influence its demand. These factors can be split into two categories: those linked to the value of transactions for which money is used (cash-financed transactions); and those linked to the stock of money required to undertake those transactions (the velocity of circulation of money). https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/1994/the-determination-of-mo-and-m4.pdf

Neil,

“They are only not related to macroeconomic tendencies in mainstream thinking – which as we know here is utterly devoid of any intellectual value.”

Its not mainstream economics per se but kindergarten economics.

I’m wondering:

in Oz and the US, central banks made the mistake of pumping borrowed funds into bank accounts of citizens, over and above what was needed to pay essential bills during the lock-down, leading to the current excess spending capacity into supply constrained economies, which is now causing inflation (especially in the US).

“Its not mainstream economics per se but kindergarten economics.”

Exactly. However here we prefer adult economics that understands the economy is the interaction of thousands of agents doing their own thing.

And the aggregate emerges from that – not anywhere else.

“Neil. If the non-government sector hoards the governments spending, it does not matter what the transaction tax rate is, the “spending multiplier” and “auto-stabilisers” won’t operate; the government sector just has to keep spending new money. ”

Of course it does – because financial savings are voluntary taxation.

MMT starts with the identification of the tendency of the non-government sector to save in the currency of issue. That’s why there’s an imbalance that has to be addressed, which is addressed via the labour market buffer stock.

Amusingly it is much easier in a fully dollarised economy, since then you just run a balanced budget. Tax to free things , hire what becomes unemployed.

The U.S. government ran a surplus of $129 billion in the first quarter of 2022 ending January. What does that say with a Fed that is raising rates to slow things down and a fiscal policy that is getting tighter?