I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

Some thoughts on a five-year development plan for Timor-Leste

Some years ago, I did some work for the Asian Development Bank on Pakistan and Central Asia. It was a really interesting experience because it taught me a lot about the challenges facing poorer regions who have dependencies on imported energy and food and limited export opportunities. Since then I have been studying a number of countries and am convinced that development strategies have to fundamentally change if the poorer nations are to achieve any hope of sustainable development. At present, I am working on the development of such a framework, which will incorporate the best-practices proposed by scholars who similarly reject the traditional IMF/World Bank development model. Specifically, I am focusing on Timor-Leste, which is about to stage a presidential election (March 19, 2022). Xanana Gusmão’s party – National Congress for Timorese Reconstruction (CNRT) – has backed former president Jose Ramos-Horta against the incumbent Fretilin President, Francisco Guterres and the third candidate Martinho Gusmão (United Party for Development and Democracy – PUDD). It appears that if Jose Ramos-Horta is elected, there will be a dissolution of parliament and early elections will be held after a period of political turbulence following the 2017 election. Early indications are that Ramos-Horta is well placed after the conduct of Guterres in recent years. The new government must consider a new development strategy and so I am working to provide some structure to that goal from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective.

Setting the scene

Timor-Leste – first gained independence on November 28, 1975 from the Portuguese.

But we know that soon after (9 days), it was illegally invaded by Indonesia and a harsh occupation ensued that would last for 24 years and ended in Indonesian military troops devastating the infrastructure of the little nation as it was forced to leave under a UN-sponsored act of self determination.

It became a new state in its own right on May 20, 2002, nearly 20 years ago.

As an Australian I have borne the shame that our Labor government brought on us when it was complicit in the Indonesian invasion and the murder of investigative journalists at Balibo.

The Australian government has also been shameful in its territorial disputes with the new nation – as it tried to deprive TL of oil reserves. Australia also spied on the Timor-Leste during these negotiations (Source).

We have short memories. The Timorese incurred massive costs during the Second World War from the Japanese occupation, while helping to shield Australian soldiers who were fighting there.

I have written about Timor-Leste before:

1. Advanced nations must increase their foreign aid (April 7, 2021).

2. Labour force trends in Timor-Leste continue to point to a need for a Job Guarantee (October 15, 2019).

3. Timor-Leste – challenges for the new government – Part 3 (May 24, 2018).

4. Timor-Leste – challenges for the new government – Part 2 (May 16, 2018).

5. Timor-Leste – challenges for the new government – Part 1 (May 15, 2018).

6. Timor-Leste – beyond the IMF/World Bank yoke (November 20, 2012).

7. Why didn’t they build better houses! (December 30, 2004).

Now, after 20 years of nationhood, the next several years will be crucial for the nation’s future.

The first 20 years has seen a lot of progress funded by the oil revenue that they have enjoyed.

The problem now is to diversify the economy and deal with the on-going problems of food security with a reliance on imported products, inadequate water reticulation and flood control, unstable incomes, particularly in the rural areas, which compromise export quality and more.

Most farming activity remains at the subsistence level.

The Asian Development Bank provides – Poverty Data – for Timor-Leste and in 2014, the poverty rate was 42.8 per cent.

Their data shows that 30.9 per cent of people suffer from undernourishment (2019), 51.7 per cent of children under five years suffer stunted growth from lack of food and 9.9 per cent suffer wasting (malnutrition).

In March 2021, Timor-Leste endured massive flooding after a period of extreme rainfall. The floods caused substantial damage to the infrastructure – wiping out bridges, roads and several deaths. Dili endured massive damage.

The problem is that flooding on the island is not a once-off event.

The regular incidence of flooding is the result of a lack of planning and investment in water management systems as well as poor farming methods.

Up until now, the government response has been palliative rather than going to the nub of the problem.

The floods recur because the mountainous farming areas have not cared for the land over the decades, which has created low permeability in the soil, so when it rains, the water just gushes down the rivers to the coast and the capital.

The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction media release (January 29, 2022) – Timor-Leste floods teach costly lessons – reports that:

The floods … the worst the country has seen in 50 years, affected 13 municipalities and 30,322 households, destroyed 4,212 houses, and took 34 lives … Roads, buildings, and public infrastructure sustained damage. Agricultural areas covering 2,163 hectares were impacted and irrigation systems were wrecked.

Nearly a year later, roads remain impassable and other infrastructure is yet to be repaired as a result of delays in getting international aid.

The UNDRR also note that “Obstructed waterways – which are dry most of the year and only fill up when it rains – was named the biggest culprit in the catastrophe. As Dili grapples with the rising demand for shelter because of in-migration, people erect houses along waterways.”

Think about this – in the first two decades of nationhood, the – Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund – had accumulated $US17.7 billion by 2019 (Source), but recent discussions with those on the ground tell me that it is now $US19 billion,

In the blog posts cited at the outset, I have discussed the petroleum economy issue in detail.

In 2019, it earned $US2.101 billion and transferred only $US969 million to the ‘State Budget’.

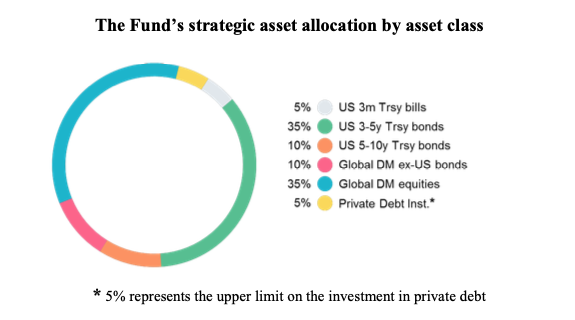

Its portfolio as at 2019 was distributed according to the following graph.

Why they are investing in low-yield US government debt instruments is one issue, which I will deal with another day as I work on this project more over time.

There is always a tension in these situations between saving for the future and investing now to make sure there is a future.

That is where the problem lies and in developing a 5-year plan to take the country to the next level after the elections will have to deal with that issue.

The other issue that the nation has to deal with is their use of the US dollar. I indicated to relevant parties in a meeting the other day that Timor-Leste cannot be sovereign and independent until it has its own currency.

And to achieve that desirable aim requires a carefully thought out transition plan to be developed to ensure the new currency is a positive step rather than becomes the target for destructive speculation by the financial markets.

I will write more about what a blueprint might look like in that regard somewhat later when things become clearer in the political circles.

Towards a sustainable growth path

My work on Pakistan and the so-called CAREC nations of Central Asia some years ago emphasised that at the outset policy makers had to achieve an understanding of the functioning of the monetary systems of sovereign nations.

Such an understanding of the options available to a nation operating with a sovereign currency must be developed first in order to appreciate the policy space that is available.

This allows for a strategy for development that is feasible while exploiting as much of the policy space available, consistent with the goals of policy-makers.

Policy-makers might choose to use less space than is available, but they should at the very least understand which policies are feasible.

The problem facing many poorer countries is that the IMF and the World Bank consultants have told the goverments that their policy space is close to zero and can only be expanded by austerity measures in the domestic economy while transforming the subsistence agricultural sector into a debt-laden, export sector producing cash crops (to pay off the debt).

When world prices for crops fall, the IMF and World Bank, just extend more loans with harsher conditionality, and the nations get nowhere.

A sustainable development strategy requires that:

1. Material living standards rise.

2. Internationally recognised human rights are advanced.

3. Economic sustainability is achieved – the nation cannot be at the mercy of export markets.

4. Environmental sustainability is achieved – farming and urban systems (water, electricity, etc) have to evolve.

When I have been working in these types of nations, the predominant theme is that if the government pursues a domestic policy of full employment (with the introduction of a Job Guarantee being a central innovation to eliminate chronic joblessness), the balance of payments problems will become worse.

The idea is that if income levels rise as more people have employment security, then imports will rise and current account constraints on growth will impinge.

In general, under fixed exchange rates, the so-called stop-go constraints on growth were always a problem facing an economy with high unemployment.

Contractionary policies were required because the current account influenced central bank reserves and made domestic expansion dependent on the defence of the external parity.

Under floating exchange rates the constraint is not binding and domestic policy can pursue full employment targets leaving the exchange rate to absorb any adjustment.

But it is clear that a further source of cost pressure could come via the exchange rate for small trading economies with flexible exchange rates.

First, the higher imports (which is not an inevitability) may promote exchange rate depreciation. Second, depending on export and import price elasticities, net exports may increase their contribution to local employment and demand.

This becomes the obsession of policy makers and militates against pursuing sustainable domestic policies.

For example, when I was working on Pakistan’s development options during the GFC, the Economist magazine published two inflammatory articles.

1. The Last Resort (October 25, 2008).

2. Pakistan’s wounded sovereignty (October 29, 2008).

Quotes include:

– “Pakistan faces economic meltdown … The economy is close to freefall. The country needs at least $3 billion in short order, and a further $10 billion over the next two years to plug a balance-of-payments gap. Without it, default abroad might well coincide with political anarchy at home.”

– “Without foreign help, Pakistan won’t be able to afford its imports, repay its debts, or quell the insurgents encamped within its borders.”

– “Pakistan is running out of hard currency. It spent $3.6 billion on imports in September, including a $1.5 billion petrol bill that was 180% higher than a year earlier but earned only $1.9 billion from its exports.”

I will tell an interesting story about my Pakistan work at a later date – which will reveal IMF bullying of a major international development institution and the government. It was a fun time.

But the point is that it is the Balance of Payments issues that become the focus for nations that import much more than they export.

For Pakistan, the government clearly needed time to deal with the burgeoning balance of payments deficits and the unsustainable loss of foreign exchange reserves.

The mainstream economists advocated harsh austerity as the solution.

My recommendation was quite different.

The financial problems facing nations like this should not be seen in isolation from the real problems – the constrained supply and the persistently high rates of labor underutilisation.

If such nations just concentrate on the financial issues they narrow the range and scope of policy options and, ultimately, limit the capacity of the economy to redress the real problems.

A viable policy framework must seek to solve both sets of problems and provide a sustainable development path.

In the case of Timor-Leste – we recognise that a robust growth outcome will tend to generate a current account deficit because of nature of its dependence on imports.

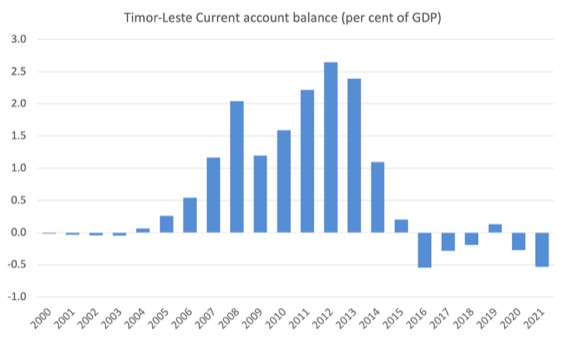

The following graph shows the current account balance from 2000 to 2021 as a percent of GDP.

The reality is that I would expect that to grow as oil revenues decline.

The IMF approach that imposes austerity, reduces capacity utilisation and suppresses domestic demand, does not provide a sustainable development path. It tends to create a vicious circle with further balance-of-payments problems.

Timor-Leste’s challenge is to create more domestic policy space to pursue an alternative, sustainable growth path. It can do that in two stages.

First, within the current dollarised monetary regime using its massive Petroleum fund holdings as if they are a currency issuer. Clearly, that cannot be the indefinite future strategy though given the fund only has $US19 billion in it.

Second, introduce their own currency, float it on international markets, run their own interest rate policy and only issue debt in local currency.

Then they have to deal with the exchange rate issue.

In the medium-term, it can make use of the considerable policy space it has (see below) to pursue economic growth and rising living standards, even if this means expansion of the current account deficit and depreciation of the currency, which is possible once it abandons the US dollar.

Of course, continuous currency depreciation cannot be sustainable.

While there is no strict balance-of-payments growth constraint in a flexible exchange economy in the same way that one exists in a fixed exchange rate world, the external balance still has implications for foreign reserve holdings via the level of external debt held by the public and private sector.

Moreover, the evidence shows that, in the long-run, no country can grow faster than the rate consistent with balance on the current account.

Sooner or later the market penalises the country and attracting capital inflows from abroad becomes very difficult.

I have a detailed paper coming out on this topic which I will make available when ready.

So part of the development strategy for Timor-Leste has to be in preparing its domestic policy space to deliver short-run gains on the road to sustainability, while getting the nation ready for the introduction of its own currency.

That strategy must include policy initiatives that reduce its dependence on imports.

In a 2008 paper – Second-best Institutions – Dani Rodrik emphasised that development strategies must recognise the contextual nature of policy solutions and to tailor the policies in a trial and error manner.

This is in contradistinction to the IMF/World Bank approach that imposes a one-size-fits-all, Washington Consensus model onto all nations.

Strategies that just create growth are also inadequate and in early stages of development rarely address the structural problems that need to be overcome.

Indeed, barring calamity (GFC, floods, pandemic), Timor-Leste has demonstrated robust growth capacity.

As noted above, poverty is high, food security is compromised, basic infrastructure is insecure and joblessness is high (especially in the informal sector).

In the short-term, the Timor-Leste government has substantial financial resources available to it to fast track an alternative development strategy away from an export-petrol economy dependence.

I consider the essential components of this alternative strategy to be:

1. Introduce a national Job Guarantee to provide income security – this will be especially beneficial in the rural, farming areas where crop quality is often compromised because the workers don’t have enough income and try to harvest too early to pursue export markets.

I am working on the parameters that might define such a policy as more data comes in.

A $US100 per month wage would, for example, improve the circumstances for the nation substantially. More about this another day.

The Job Guarantee program can be designed to increase export capacity which can help mitigate any rise of imports caused by rising consumption by participants in the program.

But the program can also be designed to reduce import dependency on food etc.

2. Reorient emphasis toward employment-creating policies and away from growth-for-its-own-sake policies. Growth must be placed within the context of achieving full employment with price stability.

3. Reformulate tax and transfer policy: (i) replace regressive taxes with progressive direct taxes to reduce the burden on low-income and low-wealth households; (ii) switch from price subsidies to income subsidies with clear targeting mechanisms for poor households; (iii) protect vital social and economic services when poverty is increasing; (iv) allot funds to address the power and water shortages; and (v) eliminate subsidies to rent-seeking sectors.

4. Diversify the country’s export basket with a view to promoting those sectors that will lead to sustainable economic development in the long-run.

The aim of this development strategy is not to direct domestic resources toward production for external consumers (instead of using them to produce for domestic consumption).

The objective of this program is to reduce import reliance and to diversify and upgrade the country’s export structure to develop niche exports.

5. Reject the conventional agricultural development strategies currently in vogue – the so-called ‘modernisation’ approach, whereby the nation adopts the practices of industrial agribusiness and chemical-input based agriculture.

This approach involves dislocation for local communities and technologically backward small land holders.

Within the current government of Timor-Leste is the view that the nation should transition out of agriculture, develop the land for industrial purposes and create a consumer society that relies on food imports.

Neither approach will succeed.

The alternative which should be part of a five-year plan involves so-called agro-ecology which is otherwise known as permaculture techniques.

There is now sufficient evidence from practices in India and some Latin American nations that this approach is scalable and provides a firm and sustainable platform for increasing food security and protecting land resources, while at the same time, reducing the need for imported food.

In the case of Timor-Leste a development strategy that invests heavily in sustainable permaculture will also help mediate the water problems because the land will improve its water retention capacity etc.

This strategy also allows the employment creation policies to reinforce the farming policies.

6. Develop water security policies.

7. Develop eco-tourism based on small-scale opportunities rather than the big resort-style, hotel investments that are common in poorer nations and which just worsen the energy and food import issues.

Conclusion

I will write more specifically about all this as I accumulate more data over the coming weeks.

The goals for Timor-Leste are to use its human resources more fully and more productively while at the same time ensuring it deals with the environmental issues (flooding) and the food security issues.

It must aim to increase the value-added nature of its non-oil exports – by investing in processing and improving quality control.

That will happen, in part, if income security is increased.

And that will happen, if the government ensures everyone who wants to work can.

The agricultural sector will be vital in the next five years and a permaculture transformation is essential.

My Helsinki Lectures series 2022 – ending today

I am currently presenting my annual set of lectures on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and the global economy at the University of Helsinki.

Tonight, is the last lecture in the series.

The teaching program will be:

- Tuesday January 25, 2022 – Streamed public lecture (YouTube) starting 10:15 Helsinki time.

- Wednesday, January 26 – first Zoom lecture with class – 08:15-09:45 Helsinki time.

- Thursday, January 27 – second Zoom lecture – 10:15-11:45 Helsinki time.

- Tuesday, February 1 – third Zoom lecture – 10:15-11:45 Helsinki time.

- Wednesday, February 2 – fourth Zoom lecture – 08:15-09:45 Helsinki time.

- Thursday, February 3 – final Zoom lecture – 10:15-11:45 Helsinki time.

The Zoom link for the lectures is:

https://helsinki.zoom.us/j/5354174274?pwd=OHdTdWJzSHNndHpyVkV2Y0lJUExRZz09

Meeting ID: 535 417 4274

Passcode: ETZhk9

This is an MMTed initiative.

MMTed MOOC – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century

MMTed – invites you to enrol for the edX MOOC – Modern Monetary Theory: Economics for the 21st Century.

It’s free and the 4-week course starts on February 9, 2022 (note edX adjusts the starting date for time zones, so for some the starting date will be listed as February 8, 2022).

The course is offered through the University of Newcastle edX program.

The course is self-paced so you can learn and participate as you choose. There is new material released at the start of each of the four weeks.

Learn about MMT properly with lots of videos, discussion, and more.

For – Further Details.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“develop the land for industrial purposes and create a consumer society that relies on food imports.”

I never understand this approach since it violates the very fundamental tenets of reducing risk via supply diversity.

The first rule of a nation is that it cannot run out of energy to do what needs to be done, and the primary energy input is food since that is what powers the underlying machinery of the nation (the effort of its people). Therefore if you rely on food imports you have to have sufficient diversity of supply and sufficient buffers to ensure that under no circumstances can you run short.

That process is the same as ensuring diverse electrical supplies to a hospital or other vital building. You have to follow the production chain all the way to the core and you have to make sure there is sufficient excess unused capacity so that you can get a burst from other suppliers if one fails and the buffer stocks become exhausted.

On a global scale food doesn’t work like that and you end up with a fallacy of composition.

That’s just on the import side. Then there’s the issue of diversity of exports so that you can continue to pay for the imports if one or more of your exports suddenly become unwanted by the rest of the world. Particularly if your export basket relied heavily in being a tourist destination – both physically and as a destination for the world’s financial carry trade.

Exhibit A of that issue at present being Türkiye.

I used to help guide a dissertation to one of the top civil servants from Timor-Leste (my area is research in management and statistics). There is a lot of work to be done in that office, and in all ministries in fact, if they are to run the various government agencies efficiently. But, as bill mentioned, the budget was mentioned as one of the biggest obstacles on their hands. So I mentioned then that it does not have to be the case if they just look up the literature on MMT. So, hearing something like this make my heart grows, that there is a chance for the real, better and most importantly more sustainable future in sight!

The tiny island nation of Timor-Leste, should it find the wisdom and courage to follow Bill’s counsel, build its fledgling economy according to MMT principles, would become one of the most important countries in the world: the first example of the kind of humane, environmentally sensitive development which every country must learn to embrace to avoid looming catastrophe. One couldn’t begin to estimate the massive volume of eco-tourism–and econ-tourism–that would follow.

Much of the MMT literature is on monetary sovereign countries. Am so looking forward to reading the results of your research on developing countries like Pakistan, South Africa and Timor Leste