In an early blog post - Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy (October 15, 2009)…

Timor-Leste – challenges for the new government – Part 1

The citizens of Timor-Leste went to the polls on Saturday in an effort to elect a government. The reports last night indicate that Xanana Gusmao’s Party, in a three-party coalition Parliamentary Majority Alliance (AMP, which includes Taur Matan Ruak’s group) have toppled the incumbent Fretilin leadership. At the last election (July 2017), the Fretilin Party led by Mari Alkatiri was able to form minority government (with Democratic Party support) after a third party (KHUNTO) pulled out. A stalemate emerged. Some commentators called it a ‘constitutional crisis’, in that, the minority government could not function effectively. After some years of stable politics, Timor-Leste has been going through a period of political volatility as a new generation of politicians enter the scene and replace the older stagers who were dominant at the formation of this tiny island state in 2002. I won’t go into the politics of the election battle but both major parties promised to fast-track economic development to make some dent into a growing poverty problem. This is a country that has been enduring decades of foreign occupation and before that more than 250 years of colonial servitude. The latter (Portugal) imposed Catholicism on the people while the former (Indonesia) spat-the-dummy when they were finally forced out in 1999 and destroyed vital public and private infrastructure as they marched back across the border.

Introduction

After shedding Indonesians, the next exploiters to line up (apart from the shocking treatment Australia has handed out over territorial borders) was the international multilateral institutions (IMF, the World Bank, and the UN) – the usual suspects – who made sure that economic policy would stay within tight neoliberal parameters and prevent the new independent government from creating an effective development path.

For background on the way in which the people of Timor-Leste were abused by the Portuguese, the Indonesians, Australia – the book by James Dunn (1983) – Timor: A People Betrayed – is worth reading.

The Australian government, anxious to appease Indonesia, also betrayed our own citizens, over the murder by Indonesian troops of five journalists working for Australian media at Balibo (Timor) in 1975 and the deliberately cover-up that followed. The Australian government is still refusing to release documents relating to that incident.

The movie Balibo is worth watching in that regard.

The Australian government knew in advance that the Indonesians were going to ‘re-colonise’ Timor – that is, brutally invade it – in October 1975, just a month before the invasion. We abandoned a people who had nurtured our own soldiers during the Pacific fight against the Japanese during the Second World War.

When the journalists were murdered by the Indonesians in 1975, the Australian government knew what had happened but maintained in official statements to all Australians that they were officially “missing”.

It is one of many examples of our national shame.

Falling into line with the IMF and World Bank – anti-development

When Timor-Leste finally achieved independence they fell into the neoliberal hands of the IMF and the World Bank.

The choice to adopt the US dollar as its currency and to impose strict fiscal rules on how it could utilise its massive Petroleum fund has meant that economic development has been retarded and poverty rates have increased.

Things could have been very different if the government had have adopted their own currency and utilised their petroleum resources differently.

And, looking ahead, Timor-Leste could deliver much better outcomes for its 1.2 million citizens if they abandoned dollarisation and realised that the nation needs a lot of upfront public investment in order to develop the physical and human infrastructure.

And to achieve that, the Government would have to kick out the bevy of international officials and consultants who continue to preach the neoliberal austerity bias.

In the lead up to the election, the international press was quoting a so-called “independent policy analyst” who also happens to be a postgraduate student at an Australian university, as saying (Source):

Everyone in Timor Leste has been talking about economic diversification and a focus on agriculture, but it is still unclear what they are going to do about it …

You have to spend less and deliver more – that is the hard task the future government will have to face.

That is the problem. The nation has been taken over by this austerity mindset couched in claims that “its main oil and gas fields will run dry by 2022 and it will go bankrupt by 2027”.

It will certainly go bankrupt if its natural resource revenue runs out and it continues to use a foreign currency.

In January 2018 then the Institute of Business (IOB) in Timor-Leste, which is a private for profit education provider in Dili hosted a workshop which considered whether Timor-Leste should have its own currency.

The speakers at that workshop all agreed that “it is too soon for Timor-Leste to implement a national currency”.

The so-called Timor-Leste Institute for Development Monitoring and Analysis (La’o Hamutuk) published its summary of the workshop (March 16, 2018) – 18 Years Later: Should Timor Drop the U.S. Dollar? and claimed:

In the case of Timor-Leste, national institutions have not yet proven that they can resist the temptation to print more money during economic hard times …

The biggest risk is the potential use of cheap and quick fixes for the economy – such as printing money to reduce a budget deficit or providing credit to banks – which could have devastating impacts on inflation and exchange rates in the future.

Using the U.S. dollar protects countries from macroeconomic crises such as hyperinflation, which can result from dangerous monetary policy decisions, such as uncontrolled printing of money.

In the same article, La’o Hamutuk chose to reinforce its message with this cartoon.

Yes, the Zimbabwe hyperinflation story … again.

La’o Hamutuk failed to source the cartoon but it was originally published by a cartoonist who works for the the US organisation ‘Americans for Limited Government’, which regularly rails against public employment, trade unions, fiscal deficits, China, public healthcare and education, regulations protecting workers, and all the rest of it.

They have a campaign they call ‘BuildWallNow.org’, which publishes opinions such as:

Our wall should have 2 wire fences and a minefield in between the fences. We should also have Gun Towers in strategic areas along the wall. Our gun towers should be equipped with machine guns, missiles , rockets, and plenty of grenades too. Our new Gun Tower officers should have the legal authority to kill any man , woman, or child attempting to enter our country illegally!

Crazy stuff. Extreme neoliberalism.

La’o Hamutuk claims it “provides non partisan analysis” but fails badly when it seeks to supplement its arguments with the worst propaganda that is available on the Internet.

Its assertions about what would happen if Timor-Leste was to introduce its own currency are drawn from the same extremist literature that they promote on their WWW site (without attribution).

Such organisations should be disregarded in any serious discussions of economic development in Timor-Leste.

At the same workshop, the The Minister of Planning and Finance in the outgoing government spun the usual IMF line when he addressed the January workshop (Source).

The following claims were made:

1. “critical factor is ensuring the independence of the central bank in conducting monetary policy” –

Please read – Censorship, the central bank independence ruse and Groupthink (February 19, 2018) and The sham of central bank independence (December 23, 2014) – for more discussion of that idea.

2. “Fiscal discipline, sustainability of public finances, structural reforms to ensure competitiveness and flexibility of the economy are basic requirements”.

And what is fiscal discipline according to the outgoing Minister of Planning and Finance?

Well, as you might suspect:

… fiscal discipline requires an appropriate architecture for the management of fiscal risk. Fiscal Responsibility Laws, Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Councils are the three pillars usually recommended … A robust fiscal rule is urgently needed and should probably be enshrined in Law … lower the deficit …

The usual IMF austerity straitjacket which has been shown on countless occasions to be inflexible, undemocratic and generates disastrous pro-cyclical policy interventions which exacerbate negative non-government spending cycles.

3. “The quality of public services, the reach of the social programs and the promotion of development require adequate and sustainable funding of Government”.

The Timor-Leste is financially constrained because it uses the US dollar as the currency.

But with its own currency, such a financial constraint would be lifted and the Minister’s statement would become erroneous.

4. “Sound and efficient public finance management will require the enforcement of the principle of cost recovery to ensure the sustainability and quality of services of utilities”.

Neoliberal userpays!

The claim is not supported by the evidence from other nations. Cost recovery, user pays etc deliver sub-optimal usage and when coupled with privatisation of essential services (energy, transport, water) result in inefficient, price-gouging.

The new government of Timor-Leste must decide which ‘public goods’ they wish to provide and then eschew any notion that they have to generate ‘market’ returns via ‘cost recovery’.

A vastly improved public transport system, provided free to the user, would, for example, reduce the reliance on imported cars.

In Part 2, I will consider these issues in more depth.

The resource curse

My mainstream colleagues claim that Timor-Leste has to escape the so-called – Resource Curse – which posits that “countries with an abundance of natural resources (like fossil fuels and certain minerals), tend to have less economic growth, less democracy, and worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources.”

The sort of pitiful narratives about this so-called problem extent to claiming that these nations are like “lottery winners who struggle to manage the complex side-effects of newfound wealth”.

There are claims that nations with massive natural resource wealth just squander it or use up all the available resources in exploiting the natural wealth.

Timor-Leste has hundreds of thousands of idle workers who could be brought into productive use – something like 70 per cent of those below 30 years of age are unemployed.

The problem for Timor-Leste has been that the resource wealth has been ‘captured’ by outsiders – advisors, consultants, IMF and UN officials – who have imposed a neoliberal vision on how the resource wealth should be used.

I will have more to say about the resource curse in Part 2.

I last explored these issues while I was doing field work up in the islands between the Australian mainland and Timor-Leste in 2012-14.

Please read my blog post – Timor-Leste – beyond the IMF/World Bank yoke (November 20, 2012) – for more discussion on this point.

The Timor-Leste Strategic Development Plan 2011-2030

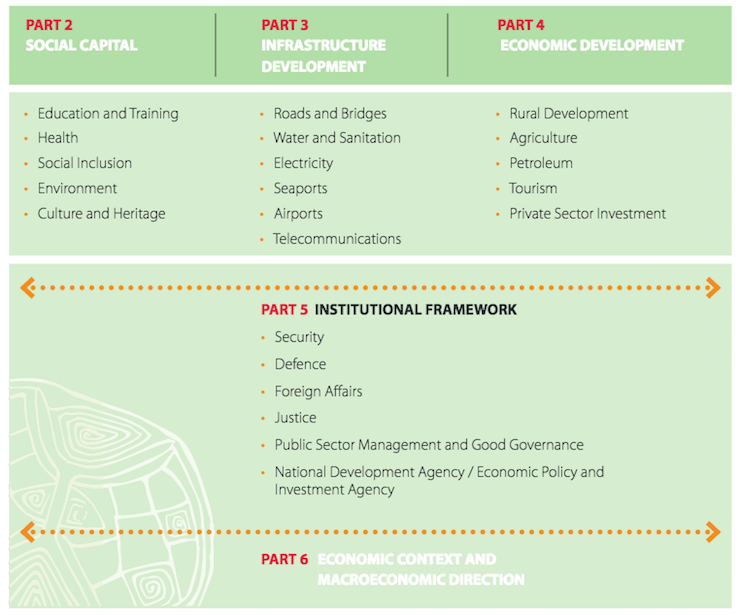

In 2011, the Government of Timor-Leste introduced their nation-building plan – Timor Leste Strategic Development Plan 2011-2030 – which aimed to fast-track the development of public infrastructure and human capital development.

We learned that:

The Strategic Development Plan covers three key areas: social capital, infrastructure development and economic

development …The true wealth of any nation is in the strength of its people. Maximising the overall health, education and quality of life of the Timorese people is central to building a fair and progressive nation.

The following graphic taken from the plan outlines the scope of their ambition back in 2011.

In relation to the Strategic Development Plan (SDP), the outgoing Minister for Planning and Finance claimed at the January 2018 Workshop that Timor-Leste has:

… made remarkable progress in the implementation of the SDP.

Due to the low level from which we started, we … decided to frontload expenditures to alleviate poverty, to accelerate the building of human capital, the construction of infrastructures and the expansion of public services. However we are currently in a juncture where we ought to take stock of the challenges ahead and adopt the right policies …

Overarching the new set of policies are the goals of achieving a higher efficiency in the use of public funds and ensuring fiscal sustainability. This will require limiting excessive withdrawals from Petroleum Fund, a better allocation of funds among sectors and linking budget allocations to policies and outputs.

The creeping stranglehold of neoliberal fiscal austerity is taking hold in Timor-Leste, which will subsume the new government unless it takes decisive action to avoid the destructive IMF-style Groupthink.

But an evaluation of the SDP goals relative to the reality in 2018, would lead one to conclude that the Plan has failed.

The outgoing Minister’s claim of remarkable progress belies the facts.

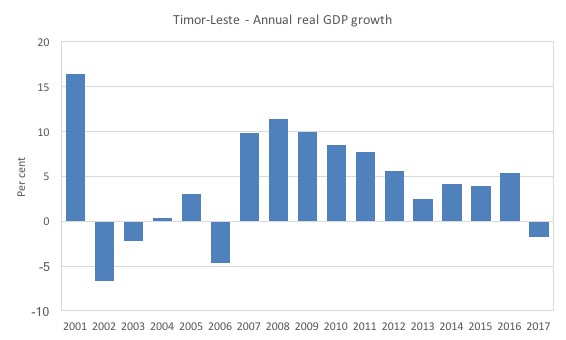

The following graph shows annual real GDP growth for Timor-Leste from 2000 to 2017, which covers the entire span of available data.

Real GDP growth fell to -1.8 per cent in 2017 after recording 5.3 per cent in 2016.

Why?

In its – Timor-Leste Economic Report March 2018 – the World Bank admits that this sharp:

Gross domestic product … growth is expected to have fallen sharply in 2017 to a projected -1.8 percent from 5.3 percent the year before. This contraction is driven by a reversal of trend, with government spending contracting in 2017 following years of positive GDP growth driven by rapidly expanding public spending …

Contracting government consumption and investment in 2017 will together exert the biggest drag on GDP growth. Overall public spending fell by 24 percent, and since the value added from government consumption and investment corresponds to 75 percent of GDP, this constitutes a very large adjustment.

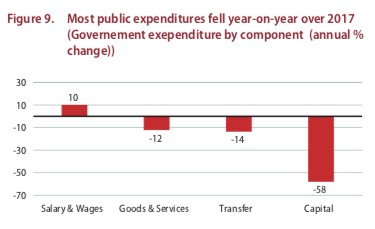

The Timor-Leste Ministry of Finance data shows that in 2017, public expenditure fell sharply.

The following graphic comes from the World Bank report cited above and shows the fiscal austerity that was imposed in 2017, as the ‘IMF fiscal sustainability’ narrative started to gain traction.

Spelling errors aside, it is no wonder growth fell sharply in 2017, given that the public sector expenditure comprises around 75 per cent of total Timor-Leste GDP.

The World Bank also claimed that “the budget consolidation that occurred in 2017 is a positive development” because it would help move the nation towards fiscal sustainability.

As we will discuss tomorrow, the IMF/World Bank concept of fiscal sustainability is deeply flawed when applied to a nation that issues its own currency.

It is even more blinkered when applied to a nation that has dollarised. Sure enough, if a nation does not have its own currency and uses the US dollar then it has to get US dollars through trade.

In Timor-Leste’s case this is via its petroleum and coffee sales, which are both invoiced in US dollars. A situation could arise where the nation can no longer generate US dollars via its external sector and so government spending would be deeply constrained.

So when the likes of the World Bank are cheering on deep cuts in government spending, which has led to a sharp contraction in real GDP growth, they are doing so in the artificial environment of dollarisation.

Do away with that currency choice, that is, if Timor-Leste adopted its own currency, then the situation changes rather dramatically.

The government of Timor-Leste could purchase goods and services that would be for sale in that currency, such as local agricultural produce, idle labour and run continuous deficits to maintain real growth and development.

The outgoing Minister for Planning and Finance told the January workshop that there was a need for tight fiscal rules to stop the government spending more than the IMF thinks it should.

He said:

Timor-Leste adopted from the start a strong framework guiding the use of its oil resources and there is an implicit fiscal rule in the governance framework of the Petroleum Fund (PF): the Estimated Sustainable Income (ESI), 3% of the Petroleum Wealth calculated yearly, may be used to finance the Budget.

However, this rule isn’t in place since sizable and increasing excessive withdrawals have been made since 2014 to fund the policy of frontloading of expenditures. Excessive withdrawals have been used not only to finance the construction of infrastructures but also to finance recurrent expenditures. There is currently no constraint to public expenditures and the incentives for the efficient use of public funds are weak. Moreover, following recent trends of excessive withdrawals would lead to a more or less rapid depletion of the resources of the PF.

I will discuss the fiscal situation in more detail in Part 2 tomorrow.

But relating that statement to the evidence, if the Government had constrained its expenditure as suggested and as the IMF has been recommending, then the GDP growth situation, which between 2013-16 was moderate to say the least, would have been much worse.

Even the World Bank acknowledges that the collapse in GDP growth in 2017 was directly due to major cuts in government spending motivated by a misguided (IMF) concept of fiscal sustainability.

A nation cannot develop if it is contracting due to fiscal austerity.

Other indicators are similarly indicative of a failing development strategy in recent years as the conservative forces mount.

According to the World Economic Outlook database, in 2010, Timor-Leste was ranked 116th (out of 192 nations) in terms of Gross domestic product per capita (Purchasing power parity; international dollars).

The figure was 6,623.762 units (Purchasing power parity; international dollars).

By 2016, five-years into the Plan, Timor Leste had slipped to 131st (out of 192 nations) and its had fallen by 9.6 per cent to 5,986.39 units (Purchasing power parity; international dollars).

There are many dimensions of that failure.

The World Bank report (March 2018) shows that:

1. “More than 40 percent of the population is estimated to lack the minimum resources needed to satisfying basic needs”.

2. “30 percent of the population still lives below the … international poverty line”.

3. “half of all children suffer from stunting due to a lack of adequate nutrition, and calorie consumption across the population is very low”.

4. “While all income deciles have seen some growth since 2007, the top decile has also seen the fastest increase in income” – this is a major issue and I will address it in more detail in Part 2.

5. “Chronic malnutrition remains stubbornly high and is amongst the most severe in the world”.

6. “At the root of the persistent social development challenges is chronic poverty that is starkly manifested through high levels of hunger and malnutrition. Poverty, hunger and associated ill-health fundamentally inhibits households from make making investments necessary to access opportunities; good health and adequate education.”

Yet, the World Bank still applauds the fiscal austerity that is killing growth and is also standing in line with the likes of the IMF to place government spending in a straitjacket on the ruse that it will run out of money if it eats into the Petroleum Fund.

On April 3, 2018, the UNDP released its – Timor-Leste National Human Development Report – which showed how far Timor-Leste is from achieving anything like reasonable outcomes.

1. “A majority of young men and women, around 88 percent, experience deprivations in education”.

2. “Youth in Timor-Leste are performing extremely poorly in areas of education, such as literacy … ” etc

3. “youth are not participating in an adequate quality and variety of education, training and skills development opportunities to be able to transit successfully from education to work.”

4. “87 percent of women and 77 percent of men … did not have jobs, and only 46 percent were studying or undergoing training … suggesting that a large share of youth are idle.”

5. “Community vitality … 90 percent deprivation … low levels of perceived security and limited social support.”

6. “The private sector … provides employment to only 5 percent of the workforce”.

Overall, the outgoing government’s strategy has increasingly delivered failed outcomes.

A major shift in policy emphasis if required – towards job creation, decentralised infrastructure development, and more. I will discuss these priorities in Part 2.

Overall, the nation has to escape the yoke of the likes of the IMF and the World Bank and realise that their concepts of fiscal sustainability will leave the nation wallowing in poverty for decades to come.

The Associated Press article (April 16, 2018) – Nobel laureate blasts East Timor’s failure against poverty – reported the former President (Jose Ramos-Horta) as saying:

If I had been a prime minister for 10 years, I would have focused all those 10 years on quality education, on rural development and that means water and sanitation for the people … The study by the U.N. on our social economic indicators, particularly on malnutrition and children’s growth are extremely negative, I’d say total failure over the last 10 years

Conclusion

In Part 2, we will discuss the currency issue, the use of the Petroleum Fund, and the need for widespread public sector job creation (via a Job Guarantee).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Dear Bill

Building a wall at the border is not neoliberalism. A consistent neoliberal should favor completely open borders, as the WSJ does. Open borders allow businesses to import cheap labor and to increase customers. There is nothing more socialist and labor-friendly than immigration restriction. The driving force behind immigration is always the business class.

As a poor country with only 1.2 million inhabitants, East Timor has to import a lot of goods. If those imports can no longer be financed by oil exports, then East Timor will be in deep trouble regardless of the currency that it uses.

Regards. James

Australia’s appalling 60 year history of abuse towards Timor-Leste is catalogued in:

“Crossing the Line” by Kim McGrath.

It beggar’s belief that a country like Australia perpetrated ongoing containment of Timor’s aspirations. One of Australia’s most heinous acts was to sign the Timor Gap Treaty in 1989. The most disturbing image I can recall, and can’t wipe from my memory, from the 1980s/1990s was a photo of Gareth Evans toasting champagne with Ali Alitas on a jetliner over the Timor Sea.

Bill,

How can an impoverished country like Timor-Leste pull itself up by the bootstraps and rapidly make inroads into poverty and improvements to living conditions of the Timorese? (Put aside the possibility of petroleum industry development.)

Creating money without there being consumption and investment goods to purchase has to cause massive inflation. Inflation in a country like Timor-Leste is probably not of much consequence. The problem is that creating money will not bring forth the rapid growth in output of goods that it needs but does not have the capacity to produce. And I can’t see private international profit motivated businesses handing over goods in return for a potentially rapidly depreciating Timor-Leste currency. There may be some companies willing to hold Timor-Leste currency in anticipation that rapid development is initiated and that they might participate in ventures with long term profitable outcomes. I would imagine they would be in a minority.

It seems to me that significant international aid transfers are required to get the economy kick started so that international consumption goods (basic foodstuffs, clothing, medicines) and particularly capital goods (tractors for farming, construction equipment, for instance) can be brought into the country.

And please don’t accuse me of carrying the can for austerity here (it’s about the only thing I’ve not been directly accused of in this place yet 🙂 ).

Bill,

Just so you are clear, I would agree money financed government spending would push the real economy at a few % growth. But if 5 -10% pa growth is required, international aid goods are required.

I agree with James

Neoliberals would be for open borders and cheap labour.

James

Attitudes towards immigration are not solely informed by economics. To assert that all neoliberals support open borders is empirically false.

Bracing for “no true Scotsman” next …

“Creating money without there being consumption and investment goods to purchase has to cause massive inflation.”

You’re not creating money. You are buying labour hours and then putting them to use.

Stop thinking about numbers. Start thinking about organising the efforts of others.

The neoliberal prime directive is “You can get anything you want with money.” A border wall, if you can buy your way around it, is perfectly sound neoliberalism. If you, say, set up a low-wage factory in Timor, the border kill-zone could even be useful. It would keep your employees from getting out.

Henry The IMF institutionalised inflation and dependency in 2000. have you been here?

The solution has to be

1) Own currency own central bank

2) Capital controls especially on FPI

3) Provide everything you can domestically by using a JG

4) Then encourage FDI and help with private sector start ups domestically to take advantage of full employment

5) Then concentrate on exports and look at what you can provide other than oil once the domestic needs are met.

6) Tourism

7) IMF and World Bank destroyed with new institutions put in place with a specific purpose to help places like this.

Neil,

“You’re not creating money. ”

This is one of the problems I have with MMT.

It’s not willing to be straight up front.

It is creating money. MMTeers don’t want to use this phrase because that will immediately raise clamours from the fiscal conservatives.

MMT will also say things like:

“If inflation gets too high, pressure can be relieved by transferring labour from the Private Sector to the Buffer Stock Sector……”

Which in normal language translates as create a recession in the private sector and hope that the newly unemployed will join a JG scheme.”

Can’t use the word “recession” can we?

MMT is afraid of its own shadow and is relieved it can spin a line.

“You are buying labour hours and then putting them to use. ”

You are buying labour hours with income not represented in the normal stream of goods and services.

So, a recession has been created in the private sector, i.e fewer goods and services will be produced and on the other hand the effective nominal income the JG schemers will add to aggregate demand. I don’t see this as a recipe for keep inflationary pressure under control.

Please disabuse me of this point of view.

Henry@ 7:44- the MMT idea is that the national government can (and should) keep the economy at full employment using fiscal policy, mainly through expanded automatic stabilizers, especially the Job Guarantee. This fiscal policy is designed (or intended) to react to changes in the PRIVATE sector’s desires to save more or save less. And I agree with you that when private sector demand falls, and a recession would ensue from that- then MMT recommended policy could be described as using fiscal policy to ‘create money’ and have the government spend it to restore demand to the economy. And when private sector demand rises past the point where the economy can increase production to meet it, the MMT recommended policy is for the government to reduce its own spending and/or increase taxes so as to reduce overall demand in the economy.

But much of both of these is supposed to happen automatically due to the hugely bolstered ‘automatic stabilizers’. And I don’t agree that a fair description of what MMT recommends could call that trying to ‘create’ a recession. It is a government fiscal policy REACTION to the private sector’s changing desires. And, again, much of that is automatic. And the whole point is to try to avoid either recession or inflation while avoiding the many problems of unemployment and while also maintaining the labor part of the supply side in a condition where it could function as a better deterrent to inflation than present policy does.

So really Henry, please be fair and not describe what MMT says as ‘trying’ to cause a recession in certain economic situations. That is not even close to being a goal of MMT. That is arguably a real goal of monetary policy as currently practiced though.

Dear eg

You are absolutely right. Not all neoliberals are in favor of open borders. However, insofar as they advocate borders that are closed or nearly closed to immigrants, then they are departing from their own 2 core principles, namely that individuals should always be allowed to be guided by their self-interest and that the invisible hand insures that we all become better off if we all follow our own interests.

When immigrants change countries, they are guided by their own interests, and employers who hire them are also guided by their own interests. Neoliberalism implies that everybody becomes better off when labor can move freely across borders, just as it implies that we all become better off if goods and capital are allowed to cross borders freely.

If the above is a no true-Scotsman type of argument, so be it.

Regards. James

“Every little East Timor is waiting for its Zheng He to be discovered”

With DF-21 the annual fireworks festival at Mindil Beach may become even more spectacular especially if the marines from the well-known country choose to participate as moving soft targets.

This is what we have been desperately asking for, this is what we deserve and this is what we will get.

Jerry,

Thanks.

Sounds good in theory, I wonder how it would work in practice given the several layers of lags that interpose between action and response.

This is the problem with the term “neoliberal”. It conflates several different things: monetarism, neoclassical political economy, as well as real world social actors, like political parties, movements, and value systems. The mainstream “right” tends to be a marriage of opposites: conservative social values with loosely free market thought, so they end up promoting ideologically contradictory policies, like free movement of capital but often not people (unless they are “significant investors”, which shows a different truth). The Liberal Party of Australia is itself a marriage of conservatives and liberals, historically united to fight the common scourge of socialism and working class politics on their home ground, democracy.

It’s this conceptual indistinctness that has seen the term criticized in recent academic discussion, with the most extreme arguing that “neoliberal” simply names the things that progressives don’t like (particularly in reference to the managerial university). I wouldn’t go that far (although there is a fair amount of nonsense published under its rubric), but it does highlight the need for more clarity in contemporary ideology critique. For the purposes of MMT, in my opinion “neoclassical monetarism” is perhaps a better target, as it stays within the economic field. The problem with that is that it misses the moral basis that hides underneath, the attempt by liberal political economy to create ideal economic subjects out of the crooked timber of humanity. It’s really that moral project that gets popular traction for “structural adjustment programs” (which sound far more sinister when thought of as both an economic and social-psychological program).

I like that MMTers declines to fight a proxy battle of pure economic theory over what is also about culture and morality, but I worry that targeting “neoliberalism” is a weak point that may become an Achilles Heel in future, especially when it comes time to face the straight-edge humanities academy, who may only hear the word “neoliberalism” and miss the essential core arguments.

Dear Henry

When a person becomes unemployed because the private sector company is cutting back due to a downturn as a result of the business cycle, he/she usually gets down to the unemployment benefit centre pretty quickly. There the government provides him with a lifeline of money and he joins the ranks of the unemployed, who in normal times keep employers happy by their downward pressure on wages, but with all the problems of poverty, social exclusion and increasing lack of training and incentive to be employed again. How much better for that person and for the economy if he were offered a socially useful job and could then add his spending (with money created by government – who’s denying this?) back into the economy. That would help his old firm with rather less lag than reliance on the more meagre unemployment benefit (with money creation) stabilizer. And make him/her rather more likely to return to the private sector provided it could compete with a socially reasonable wage.

“You are buying labour hours with income not represented in the normal stream of goods and services.”

The “stream of goods and services” requires someone to buy, otherwise they don’t get made.

The income results from the buying.

Pat B,

You said one interesting thing which hits home and that is that if there is a recession the unemployed in due course receive unemployment benefits which keep the income circuit running.

And I have no problem per se with the notion of a JG scheme.

I was more wondering about dealing with an inflationary environment where a private sector recession has to be engineered, the unemployed receiving an income from the JG scheme then trying to purchase a reduced output of goods (because of private sector recession). As you point out this already happens and it probably welcomed by the private sector.

I guess it depends on how hard the private sector is driven into recession and how problematic the inflation was to begin with.

Allan,

Initially the income results from JG income. Via the multiplier process production steps up and income steps up.

It would be very interesting to see how the system would work at full employment with a strong unwanted entrenched inflation running.

Dear Bill,

I recall that in one of your blogs you have advised African governments in the past. If that is correct would there be any possibility of you advising Timor Leste? Your advice if followed (big if I accept given the current dominance of the IMF etc).

It has the potential to showcase what could be done employing MMT principles in a small country even with limited real resources.

“It would be very interesting to see how the system would work at full employment with a strong unwanted entrenched inflation running.”

I see that line used all the time.

You can substitute it for the following “First assume we are at light speed”. Which of course begs the question “how did you get to light speed”.

That question is never answered.

A key point about the Job Guarantee is that policy is kept sufficient tight that the JG buffer never exhausts in any physical location within the currency zone. Since private sector jobs are no longer vital, you can ensure competitive pressures are maintained and the disciplining nature of the Job Guarantee stays intact.

Neil,

“I see that line used all the time. ”

It must be very comforting to implicitly know that MMT will work every time, on que, as planned, as theorized etc., etc..

In 45 years of adult life I have yet to see an economist consistently make valid predictions.

Perhaps MMT will break the mould.

You have clearly been looking at the wrong economists.

More seriously, Bill’s series of blog articles are fully of condemnations of his own profession.

Perhaps it will. Let’s try it and see.

Hi Bill

I don’t have a view on your anti-austerity position generally, as it relates to the situation in recent years in Europe and North America. But you have it totally wrong in relation to Timor-Leste. Sadly you seem to have brought an ideology to your reading of the scant evidence you have looked at, and seriously misread it. All the experts you quote – Rui Gomes (Min of Finance), La’o Hamutuk, Guteriano Neves would argue for substantial increases in public expenditure on “human capital” (health, education, industry support that creates employment, etc). The reductions in spending they argue for are in expensive “physical capital” projects that have dominated the national budget, done little to generate employment opportunities and have questionable benefits for long run growth in the economy.

Dear Henry

Firstly, re:’make valid predictions … perhaps MMT will break the mould’ My understanding is that MMT offers firstly a valid, empirically based analysis of macroeconomic reality. From that starting point, any predictions are likely to be more reliable than say, based on a theory such as Ricardian Equivalence which has no basis in reality.

Re: ‘an inflationary environment where a private sector recession has to be engineered’ and ‘the private sector is driven into recession’. Where is this inflationary environment and who drives the private sector into recession?

I think Mark Blyth (while Professor Mitchell is an unfailing source of valid macroeconomic analysis, it’s always good to read around, though with heightened awareness for nonsense) does a good job in pointing out that the post-war period of gradually building inflation leading to the 70s, where this was combined with two inflation spikes both triggered by drastic oil price rises, was historically unusual. And yet it’s been used ever since as an inflation bogey. A job guarantee scheme provided with a socially acceptable wage floor, is not the same as a public sector with (non job guarantee) employees, competing with the private sector in a 1945-1970s environment. I believe Professor Mitchell has previously pointed out that MMT (with integral job guarantee scheme) is politically neutral in the sense that it doesn’t prescribe a big or small public sector, though the room for reacting to private sector economic swings is greater if the public sector is of at least a certain size. The government/public sector does not ‘drive the private sector into recession’. Political views and taxation to create fiscal space determine the desired ratio of public/private sectors. From there it’s perfectly possible to plan public sector schemes (not job guarantee) to be sufficiently flexible in terms of turning on/off spending to react to the private sector’s inevitable swings. One could (should) of course regulate bank lending to control its potential inflationary impact just as one would want to ensure that government created money/spending didn’t ‘get out of hand’, for the same reason.

Just responding to the blog post.

A country that has energy reserves and has population that has lived to the 21st century now faces unprecedented problems because we have… more technologies? more labor available? when everything is better than they used to be? Makes no sense.

You literally can have everything you need to develop and ensure citizens will have healthy fulfilling lives (not even asking for luxurious life style), but you can’t kick the ball into the goal net.

Its incredibly frustrating to see wasted potential. You are right, economics is garbage. Calling for abolition of IMF and world bank is the responsible thing to do.

Dear Brett Inder (at 2018/05/16 at 10:31 pm)

Thanks for the observation.

The “scant evidence” is years of studying Timor-Leste including most official documents and thousands of pages of books, academic articles and other commentaries.

And I think you have missed the point about austerity. There is a compositional and level difference. In Part 2, yesterday, I noted that there was a debate about composition and I deal with that more in Part 3, which is coming out next week. Yesterday, I cited the controversy over the South Coast Highway development, for example, and indicated that there was a need to redirect expenditure to job creation and education and training as a priority.

That is consistent with the “experts” you cite and agree with.

But where austerity enters the picture is at the level. All of your “experts” have at various times called for less overall public spending. Some have gone further to articulate an IMF vision of fiscal sustainability, which requires significant cuts in spending levels in Timor-Leste.

Within that (neoliberal) narrative, they may well agree with me that the composition of spending needs to change but they all want that shift done within a framework of lower deficits and closer adherence to the ESI straitjacket.

My point of difference is that there is a need for much more public spending (higher deficits) than say was recorded in 2017 and greater draw down from the Petroleum Fund.

You do not seem to have picked that up difference. Austerity is principally about levels not composition.

And, of course, we differ fundamentally on the urgent need to introduce a national currency, which I addressed in Part 2. I also formally expressed that view at the time the UN Transitional Administration was railroading the nation into the US dollar. That was long before you were doing any work on Timor-Leste.

best wishes

bill

Brett Inder,

I don’t think you have been paying attention to what the so called Timorese experts have been saying?

Guteriano himself has said, in defence of his arguments, that Government should be given less money so they have less money to play with because they don’t spend it properly. There is no argument about whether Government should spend on some projects or not. The response from Gute and other so called experts is akin to saying the Government should be treated like the unemployed or Aboriginal people in the NT – they waste their money say they should have less money to spend overall. When questioned what do they respond “ideology! ideology!”

Furthermore, Gomes party has never been able to address the fundamental economic questions. They have had a few chances now. They ran the now rejected ordoliberal project in Oecusse and whilst chanting they are revolutionary they repeat the mantras of the IMF and World Bank. Did you see what the people thought of that project on Saturday? How it had improved their lives?

Their PM sat on his hands during the UNTAET administration, whilst the macro economic fundamentals that govern the country were put in place. He claimed he would reverse them during his 25 year reign of government that was to come. Instead as Bill has pointed out they just now repeat the same mantras.

Sadly, there are too many Australian academics who fly in and out of Timor who have no real contact with the people outside of their own small circles. But they are always willing to come in and pontificate and reinforce the country’s structural dependency. They like to come and sit in the Hotel Timor or the Esplanada and big note themselves in front of their peers or the students that they bring in toe from Melbourne. But do they really help the country? How many of them are really economists?

Why is it all the yes people of this dependency cry out “ideology! ideology!” when they are faced with a critique of the paradigm within which they operate. Surely, you can do better than that? Or at least show us how the policies you seem to want to promote assist this country in a manner other than to reinforce that paradigm. It is all a little TINA to me.

Bravo to Bill for doing some hard work and trying to propose alternatives that the Government can seriously consider. If you can add anything positive I would love to hear it.

Greetings from Aileu

M

Pat B,

“….empirically based analysis of macroeconomic reality….”

It seems to me that MMT is based on a factual analysis of clearing and payment systems – the rest is theory.

Where’s the empirical basis supporting the successful implementation of a JG scheme and the ability to run a stable (i.e. controlled inflation) economy with a stable currency? It’s all a matter of opinion, isn’t it?

I’m not saying it’s not possible, but where is the real world, experiential, hard evidence?

Dear Henry Rech (at 2018/05/17 at 11:45 am)

Not at all.

You live in a nation that used buffer stocks to control prices – the Australian Wool Price Stabilisation scheme.

That is where I got the idea of the Job Guarantee from while studying agricultural economics.

That scheme had issues but it certainly controlled prices.

Buffer stock schemes have been used often in history for that purpose. There is a long literature and a mass of experience.

best wishes

bill

” but where is the real world, experiential, hard evidence?”

How do you study the movements of a man, when all the data is from men in straitjackets?

The hard evidence from current economics is that it causes an endless sequence of disasters for actual people, and can’t predict anything of note. Which makes it more in keeping with religion than science.

Bill,

“…the Australian Wool Price Stabilisation scheme….”

OK. However, managing an unemployed wool bail is not quite the same as managing an unemployed human being.

Anyway, I was picking up Pat B on his claim about “empirically based analysis”.

Given your response and Neil’s, there doesn’t appear to be much about.

Many thanks for your thoughtful analysis. I was most interested in your observations about Lao Hamutuk. It was under the effective control of US folk since its inception. They, particularly one Charlie Scheiner, put himself forward as the voice of Lao Hamutuk when I interviewed Lao Hamutuk during my evaluation of the splinter group Luta Hamutuk’s program funded by Caritas. Luta Hamutuk was founded and managed by Timorese with no foreign staff at all and were in serious philosophical conflict with Lao Hamutuk.