I have closely followed the progress of India's - Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee…

Income support for children improves brain development

When I first came up with the idea of a buffer stock employment approach to maintain full employment and discipline the inflationary process (back in 1978), the literature on guaranteed incomes was still in its infancy. The idea of a basic income guarantee was still mostly constructed within the framework Milton Friedman had laid out in his negative income tax approach, which I first came across when reading his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, while I was an undergraduate. I wasn’t taken with the idea and the preferred an approach to income security that not only integrated job security but also had a built-in inflation anchor. When I developed that idea, inflation was still conceived of the main problem and governments were fast abandoning full employment commitments because mainstream economists told them TINA. I thought otherwise. However, as I developed the buffer stock approach further in the 1990s as part of the first work that we now call Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), nuances about additional cash transfers became part of our approach. I refined those ideas in work I did developing a minimum wage framework for the South African government in 2008. I was reminded of all this when I read a report in New Scientist last week (January 24, 2022) – Giving low-income US families $4000 a year boosts child brain activity. Some might think this justifies the BIG approach, whereas it strengthens the case for a multi-dimensional – Job Guarantee.

Some work I did in South Africa

In 2007-08, I did work in South Africa that was funded by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and focused on the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) in South Africa, which culminated in several reports.

The ILO initiated this research in accordance with its commitment under the UN Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) for South Africa to support South Africa in addressing the problems of the “second economy”, and as part of its technical assistance to the Government in implementing the Public Works programme.

The Government has adopted a number of measures to reduce poverty and promote employment – primary twin-problems of the “second economy”.

The EPWP was the only programme with both employment and social protection elements directed to the working-age population who are able to work and willing to work but cannot find work.

We engaged in a series of consultations from March to October 2007 with the EPWP programme managers and implementers, key policy makers, social partners and academic experts which helped clarify the issues and identify research questions that would be useful inputs to national debate on policy choices.

One of the reports, published on June 12, 2008 – Assessing the wage transfer function of and developing a minimum wage framework for the Expanded Public Works Programme in South Africa (252 pages) – considered, among other things, what extra assistance a Job Guarantee program would require to reduce poverty.

I considered how to deal with spatial price level differentials where prices and spending patterns vary significantly across space – in particular, between the more expensive (but higher quality) urban areas and the less expensive rural areas.

One recommendation was that where spatial cost-of-living disadvantage can be clearly identified and estimated, adjustments are made to social grants – such that a zone allowance might be paid to the worker via a social grant.

In developing the minimum wage framework designed in the first instance to provide a buffer against poverty, I also had to consider household size.

Note that the general Job Guarantee idea ensures a socially-inclusive minimum wage, which would be well above traditional poverty line estimates.

In the South African case, we initially were seeking to build a framework that provided, in the first instance, a buffer against poverty, which would give the government time to expand the things that the mininum wage could achieve.

The problem was that setting a minimum wage that will provide a buffer against poverty was complicated by the fact that household size and composition varied across the population.

This problem always bedevils efforts to set poverty lines because there are considerable differences in household consumption patterns.

I came to the view that it would have been too unwieldy to build adjustments for family size and age composition into the EPWP minimum wage determination framework.

Instead I recommended that poverty line measures be equivalised where possible (and achievable) and that the social grants system used through family assistance grants to supplement the EPWP wage.

I also recommended a scaling up of the social wage to ensure that essential public services such as education, health and aged care and the like are provided in adequate supply.

This public goods approach to services reduces the need for households to have private income.

If you consult the report, You will see that I devoted considerable attention to the alternative argument (against the EPWP) that the social grants system should just be expanded to some form of BIG as the primary means through which the fight against poverty is conducted.

I argued that the EPWP should be progressively scaled up to become a true employment guarantee rather than be restricted by fiscal allocations, which meant only some workers could access the guaranteed work (about 10 per cent of the unemployed at the time).

I recommended that the current social grant system be restructured to ensure that families of workers are also able to live beyond poverty.

That restructuring would be consistent with the principle I set that no South African should be left without an adequate income if they are willing and able to work.

And, for those unable to work because of age, disability, illness or child-rearing, the primary source of poverty alleviation should be an upgraded social grant system.

The New Scientist report

Kimberly Noble is a Professor of Neuroscience and Education at Columbia University in the US and has done a lot of research into the neuroscience of socioeconomic inequality.

Neuroscientists have long considered there are “links between a child’s socioeconomic background and the structure of the brain” although to date the evidence has been “correlational”, meaning lacking in clear causal understandings of what the links mean.

Kimberly Noble’s research team have sought to understand:

… how exactly child poverty causes reduced grey matter volume in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, which is associated with the subsequent development of thinking and learning. These changes have been seen throughout childhood and adolescence.

Their study tracks brain development in “1000 babies from low-income families in four metropolitan areas” across the US.

The families had an average income of $US20,000 per annum.

The US Census Bureau reports that the – Median household income (in 2019 dollars) – was $US65,712.

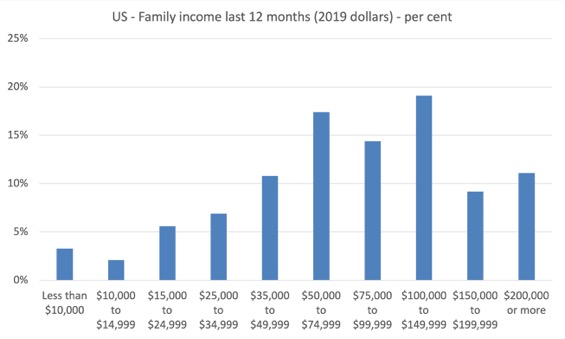

We also learn from – Table S1901 – that 11 per cent of US families had a 2009-inflation adjusted income over the last 12 months of less than $US24,999.

5.6 per cent of families had incomes of between $US15,000 and $24,999.

The average income for all families was $US108,587, with 11.1 per cent receiving $US200,000 or more.

The following graph shows the full distribution from Table S1901 – it is highly skewed with some very high income recipients biasing the average.

The point is that the families that the neuroscience team targetted for their study are very low income recipients and likely to suffer significant material deprivation.

The team:

The team gave half the babies’ mothers a monthly stipend of $333 and the other half $20 a month. The first payment was received soon after their baby’s birth.

So the $US333 a month is about $US4,000 per annum, which other studies have indicated leads to “improvements in a child’s school performance later in life.”

For example, a Harvard scientist (David Weissman) and team found that higher welfare payments in the US “can reduce the impact that living in a low-income household has on the size of a crucial region of a child’s brain” (Source).

The crucial region – the hippocampus – is “involved in learning and memory” and “kids with small hippocampal volumes are more likely to develop internalising problems … and develop depression”.

Back to the Columbia research.

The parents could spend the transfers any way they chose.

At the first birthday, 435 kids were checked for “their brain activity” – 40 per cent in the lower transfer group and 60 in the higher group.

Covid prevented the full sample being tested.

The results are stark:

… on average, children from families that received $333 a month had more brain activity in higher frequencies than those in the $20 group.

These frequences “predict skills that are important for thinking and learning” as the child gets older.

In general, one of the consequences of poverty is less “high-frequency brain activity”.

Why did the higher payment improve the cognitive development of the young children (babies)?

The researchers think that the higher payments “changed the home environments of those babies”, perhaps overcoming the typical stress that poor families endure, which undermines brain development in children.

Kimberly Noble was quoted as saying:

The fact that we did see effects after just one year really speaks to the remarkable plasticity of the developing brain and its sensitivity to economic resources.

As more research along these lines comes in, it is clear that governments have to do everything they can to resolve the poverty question.

My work in South Africa, and, later in indigenous communities in Australia, clearly supported this type of research.

Two aspects are important:

1. Reducing family stress by ensuring the adults can gain employment at a socially-inclusive wage. There is little thirst among adults that I have studied for a BIG if a job is available.

The income security arising from guaranteed work helps families risk-manage better and improves the environment for their children.

There is less anxiety.

2. Providing additional income support where family circumstances warrant to address size differences, other family issues (such as disability, etc), to make sure children get adequate learning support.

Conclusion

That additional support to supplement the Job Guarantee in no way makes a case for the introduction of a BIG.

Families want to work.

But that alone may not be enough, even with a socially-inclusive minimum wage provided, to address the diversity of family structures that exist.

The bottom line is clear – children suffer massive disadvantages from growing up in poverty.

Unemployment is one of the principle causes of poverty.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Obviously I’m not up to speed on employment related jargon!

A BIG is what exactly?

While the authors’ conclusions seem plausible, the results of the study on cash payments and infant brain activity by Kimberly Noble’s group are a bit shaky.

There’s a detailed discussion on Andrew Gelman’s blog, including re-analyses of the data.

https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2022/01/25/im-skeptical-of-that-claim-that-cash-aid-to-poor-mothers-increases-brain-activity-in-babies/

@Stuart Reynolds

Basic Income Guarantee

Stuart Reynolds wrote: “A BIG is what exactly?”

Probably … “Basic Income Grant.” In the U.S. the acronym is more frequently UBI, for “Universal Basic Income.”

I put this on Facebook and a friend (retired special needs teacher) commented:

“Good to have this confirmed again. This has been known empirically for many, many years – but the Tories and Labour keep getting the causal direction wrong in policy. They think that more education leads to better economic outcomes; but its actually better economic circumstances in the early years which leads to better education and health outcomes (and better economic outcomes through life). Whilst Labour SureStart was good in the sense of providing support for parenting, the real issue that was needed was never properly addressed: macro-economic intervention to end child poverty; achievable with political will.”