Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

The working poor are still poor in Australia

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. Today, he is writing about the impact the recent decision by the Fair work Commission – Annual Wage Review 2020-21 – on June 16, 2021, which raised the National minimum Wage in Australia to $772.60 per week or $20.33 per hour. I am travelling most of today and so it is over, once again, to Scott …

The working poor are still poor

The recent announcement by the Fair Work Commission (June 16, 2021) of an increase to the national minimum wage (NMW) while welcome, is still woefully inadequate.

In their – Decision – the so-called Expert Panel for Annual Wage Reviews stated:

The factors the Panel are required to take into account have led it to award an increase of 2.5 per cent. The NMW will be $772.60 per week or $20.33 per hour.

This represents an increase of just 18.80 per week or $2.68 per day.

Hardly a windfall for the country’s working poor and flies in the face of the Commission’s statutory requirements to consider ‘a safety net of fair minimum wages’.

Just how shameful the national minimum wage is, can be gauged by a comparison to what others earn.

These relativities are discussed in the blog post- Australian minimum wage case decision – a scandalous indictment of our system (July 2, 2020) – where Bill shows that the minimum wage falls significantly short of what might be considered a fair wage.

Specifically, he argues

The Federal Minimum Wage is around $91 per week shy of reaching the 60 per cent of median benchmark and the gap is rising.

The data referred to in that blog post was for 2020 when the COVID-19 health pandemic was in full swing.

Twelve months on, and the picture is still the same.

Extrapolating from the Australian Bureau of Statistics data release – Characteristics of Employment, Australia – for August 2020, the new national minimum wage sits at 53 per cent of the median wage.

At this level, the new national minimum wage falls short of the Commission’s accepted poverty threshold, why they define in these terms:

In measuring poverty, we continue to rely on poverty lines based on a threshold of 60 per cent of median equivalised household disposable income and that those in full-time employment can reasonably expect to earn wages above a harsher measure of poverty.

In real terms, and given the real cut in income suffered in the previous year (2020), the working poor are barely keeping up.

This is despite the Commission acknowledging:

… that awarding an increase which is less than increases in prices and living costs would amount to a real wage cut. Such an outcome would mean that many award-reliant employees, particularly low-paid employees, would be less able to meet their needs. For some households such an outcome would lead to further disadvantage and may place them at greater risk of moving into poverty.

In the process of reaching the final numbers, the Panel took submissions from a number of stakeholders.

The unions, as they have always done, argued for a larger increase.

We learn from the Commission’s Decision announcement that

The ACTU proposed a uniform increase of 3.5 per cent to the NMW and modern award minimum wages … ACCER submitted a 4 per cent increase to the NMW …

For context, the ACTU is the Australian Council of Trade Unions and ACCER is the Australian Catholic Council for Employment Relations.

This was countered by Employer organisations who were crying poor and demanding a significantly lower rise:

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI) and the Australian Industry Group (Ai Group), Australian Business Industrial (ABI) proposed an increase of 1.1 per cent. Other employer organisations proposed an increase no higher than inflation. While the Master Grocers Australia and the National Farmers’ Federation stipulated no increase.

What is galling, is that many of the organisations that benefited from the Federal Government’s various COVID-19 economic supports were among those yelling the loudest to suppress wages growth.

The slap in the face for our working poor doesn’t end with the paltry $2.68 per day rise.

Reading through the Commission’s Decision we learn that the timing of the increase is staggered depending on the industry a worker is employed in.

Some workers will get their extra pay from July, while others will have to wait till September or November, further reducing the real impact of the rise.

The impact of this decision goes well beyond the numbers.

We know, for instance, that the financial stress faced by low-income individuals and families is significant.

The – The Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey – released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (June 16, 2021) provides a snapshot of household finances.

Reading through the figures for the May 2021 reference period we see:

Of Australians aged 18 years and over, in the last four weeks:

- 12 per cent reported their household finances had worsened (14per cent reported the same in February 2021).

While:

Over the last 12 months:

- 22 per cent reported their household finances had worsened.

In the context of this:

One in five (20 per cent) Australians reported their household took one or more financial actions in the last four weeks to support basic living expenses in May 2021 (16 per cent reported the same in January 2021) … Of the Australians who took at least one financial action to support basic living expenses in the last four weeks:

- 12 per cent drew on accumulated savings or term deposits

- 3 per cent entered into a loan agreement with family or friends

- 3 per cent increased the balance owing on their credit card by $1,000 or more.

It is not only about meeting living expenses.

Being able to raise money in an emergency is also problematic:

In May 2021, of Australians aged 18 years and over:

- 76 per cent reported their household could raise $2,000 for something important within a week

- 12 per cent reported their household could raise $500 but not $2,000

- 5 per cent reported their household would be unable to raise $500 within a week.

Besides these figures, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of the working poor having to struggle with day-to-day living.

The ABC news report (June 3, 2021) – Want a pay rise? You should care about how much Australia’s lowest-paid workers earn – on the upcoming wage deliberations reported comments from those trying to survive on the minimum wage:

It’s no good, I am working but it is not enough to live comfortably …

I go without, I put my kids first.

The point is that there are many individuals and households who struggle financially and the extra $2.68 per day isn’t going to help.

They will still suffer from multiple disadvantages.

The other disturbing point around the National Minimum Wage Decision in that it impacts on workers that recent history has shown are often key to our functioning as a healthy society.

The COVID-19 pandemic shone the spotlight on many low paid workers such as cleaners, age care workers and retail workers, who were critical to our functioning during the health crisis.

A report from the City University of London (published June 3, 2020) – The job quality of key worker employees: Analysis of the Labour Force Survey – highlighted the plight of these ‘key workers’.

The Report, which uses data from the UK labour force survey published by the Office of National Statistics, but is equally applicable to Australia, shows us:

… that the jobs which have been identified as having the highest value during the pandemic are often the lowest paid …

A number of our selected key worker occupations earn below the median pay of all employees, and some earn markedly less, most notably, cleaners, care workers, teaching assistants, nursery nurses, bus drivers, and food sector workers.

The BBC news story (January 7, 2020) – Coronavirus: Key workers are clapped and cheered, but what are they paid? – headline puts all of this in context.

The situation in Australia is not all that different with cleaners, security guards and age care staff-those identified as among the important frontline workers during the COVID crisis among the country’s lowest paid.

Many were also at the front line for community outrage when a community outbreak of the virus was detected.

This was discussed in more detail in the blog post – Why improve policy when a government can pillory a low-paid, precarious worker instead (November 23, 2020).

The message to the Fair Work Commission should be clear: These workers deserve better!

You would hope that decision such as those made by the Commission might reflect wider community expectations.

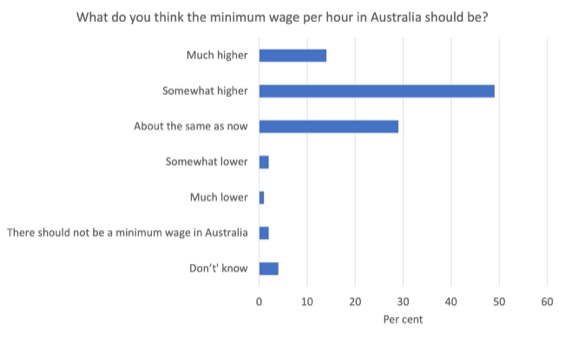

The following graph is derived from survey evidence presented in the ABC article cited above.

The responses revealed that 49 per cent of respondents thought that the minimum wage should be ‘somewhat higher’ while 14 per cent thought it should be ‘much higher’.

Very few people thought that it should be lower.

Conclusion

Ensuring that our lowest paid workers are able to fully participate in society should be a priority. They should not have to cut corners to survive.

They should not have to take multiple jobs just to get by.

They shouldn’t be subject to the multiple disadvantages that living in poverty brings.

The Fair Work Commission’s decision was full of rhetoric about fairness and equality, but in the end their decision falls flat.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Agree totally!

However in the environment of the neoliberal mantra

Keeping wages low, or debt pressure high, means workers will be less likely to complain or make demands. As workers struggle to provide their families with all the temptations that a capitalist society offers, they become far less likely to risk their employment, and less able to improve their situation.

At bottom, conservatives believe in a social hierarchy of “haves” and “have nots”. They have taken this corrosive social vision and dressed it up with a “respectable” sounding ideology which all boils down to the cheap labour they depend on to make their fortunes.

The larger the labour supply, the cheaper it is. The more desperately you need a job, the cheaper you’ll work, and the more power those “corporate lords” have over you.

Cheap-labour conservatives don’t like social spending or our “safety net”. Why? Because when you’re unemployed and desperate, corporations can pay you whatever they feel like – which is inevitably as little as possible. You see, they want you “over a barrel” and in a position to “work cheap or starve”.

The diagnosis is crystal clear but what can change the situation given employer power, Union impotence etc

We have gone so far down the rabbit hole of neoliberalism that changing the situation becomes More and more difficult.

We know what can be done to bring about a fairer, more broadly prosperous

And happier society but there are very powerful forces arrayed against it.

Being sacastic here:

Let me know when inequality is NOT increasing.

The minimum wage should be framed as a demand stimulation not simply as a cost to be born by employers or government.