In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

The inflation mania is growing – but manias are manias

The other day I gave a talk to the ‘investment’ community in Melbourne and they wanted to talk a lot about inflation, which seems to be their foremost concern at the moment. Tomorrow, I am giving a similar presentation in Sydney and I expect a similar line of questioning. Think about it. Wages growth is projected to be so low over the next several years that real wages will decline for at least 3 to 4 years. The Output gaps are still significant and were significant even before the pandemic. Households were already cutting back consumption spending growth, given record levels of indebtedness and no prospect of wages growth. Where pray tell are the inflationary pressures going to come from? I also keep reading of similar fears from economists and central bankers. The latest I saw came from Britain, where the outgoing chief economist from the Bank of England started beating on the inflation drum. There are some areas of our economies that will experience price pressures in the coming period given the disruptions in supply and various administrative pricing decisions by governments (reversing pandemic assistance in areas like rents, energy, child care etc). But these pressures in some segments of the economy are unlikely to instigate a major shift to high generalised inflation rates because the capacity of workers to defend their real wages is diminished now. Fiscal policy has a long way to go yet in reducing unemployment and underemployment from their elevated levels before that capacity becomes functional again.

Last week, the outgoing Bank of England chief economist (Andy Haldane) claimed that accelerating inflation was now a real prospect and fiscal and monetary policy would need to be tightened.

I note that this is not the scenario that the Bank of England predicted in 2016 in the lead up and aftermath of the Brexit referendum.

Then the Bank predicted very bad outcomes that were consistent with the doom predicted by the Treasury and a raft of New Keynesian economists – all part of the same crop.

On January 9, 2017, British economist Paul Ormerod wrote a piece in the Prospect Magazine – Why are so few economists Brexiteers? – where he cited Haldane (then chief economist at the Bank of England) as saying that the Project Fear that the mainstream economists in Britain ran during the Brexit referendum and afterwards during the exit negotiations was an example of:

Groupthink culture in the economics profession … The notorious projections by ‘Project Fear’ of the immediate impact of a Brexit vote have been shown to be completely wrong. But, as the Treasury document which produced the forecasts states, they were based on a ‘widely accepted modelling approach’

Haldane, of course, was part of the Project Fear debacle given the Bank, itself immediately claimed that the GDP loss would be a cumulative 2.5 per cent, which at the time was the largest ever downgrade in two consecutive quarterly inflation reports since they were first published in February 1993.

In the – Inflation Report, August 2016 – the Bank of England claimed that:

Following the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union … the outlook for growth in the short to medium term has weakened markedly … likely to push up on CPI inflation … Domestic demand growth is, therefore, projected to slow materially over the near term …

The Bank’s governor at the time, Mark Carney promoted fear when he claimed there would be a “technical recession” if the Leave vote was successful.

In the – Monetary Policy Summary and minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee meeting ending on 11 May 2016 (published May 12, 2016) – a month before the vote, the Bank predicted the worst if the Leave vote was to win – “a materially lower path for growth and a notably higher path for inflation”.

They predicted that GDP growth would fall, the exchange rate would depreciate sharply causing inflation and unemployment would rise.

They predicted that by the end of 2016, the growth would stagnate.

When none of their predictions materialised in any significant way (or at all), Haldane told the Institute for Government (January 5, 2017 – (Source), that the economics profession was in “crisis

” over its embarassing forecasting failures.

He compared the Brexit forecasting disaster with the so-called – Michael Fish Moment controversy – which saw the British BBC weather man (Fish) fail to predict a massive 300-year storm in the SE England in October 15 and go on air and deny that such an event was likely.

Now, as a parting gesture, Haldane gave an interview last week ((Source) where he predicted that there would be a strong recovery from the pandemic and private domestic spending (households and firms) would “maintain the momentum in demand”.

He claimed that “A year from now, it is realistic to expect UK growth to be in double digits”.

But this would likely push up inflation as the economy ‘overheated’ and that would introduce “collateral damage on our finances, squeezing the purchasing power of our pay and causing rises in the cost of borrowing”.

He wrote in the article:

This momentum in the economy, if sustained, will put persistent upward pressure on prices, risking a more protracted – and damaging – period of above-target inflation. This is not a risk that can be left to linger if the inflation genie is not, once again, to escape us

Usual stuff.

Brexit is was real output collapsing and inflation.

Fiscal stimulus in pandemic – output will boom and inflation.

He claims that the stimulus has to be withdrawn and the Bank of England had to cut its bond-buying program substantially as part of a weaning process.

The same inflation fear mongering is coming out of the US with the Treasury secretary and other senior Democrats singing the same song.

The UK Guardian is pushing the line too.

In the article (May 15, 2021) – The fear that haunts markets – is inflation coming back? – the “spectre of inflation” allegedly “had investors on the run last week”.

I told the audience in Melbourne the other day that if they keep listening to the advice from mainstream economists and follow their predictions they will continue to lose investment opportunities.

Many investors have lost billions trying to short sell Japanese government 10-year bonds after being told by economists that yields would rise and bond prices would fall.

That sort of losing trade has been going on for 20 or more years.

More recently during the GFC, mainstream economists predicted bond yields and interest rates would rise and inflation would accelerate and the investment firms shifted positions accordingly and lost a bundle when none of the predictions materialised.

But once again, the inflation fear is out there and spreading because economists are using their failed models and predicting the rising deficits and bond-buying programs will pump too much demand into the economy just as households go on a spending spree after increasing savings over the course of the pandemic.

Remember a once-off price spike in one or more markets is not an inflationary event. It is possible that some commodity markets will see such spikes (like iron ore at present).

Oil prices might rise.

But there has to be a more connected response from workers and firms for those raw material price rises to trigger a generalised inflation.

And, given that inflation rates fell during the worst of the pandemic slowdowns, the fact that they return to pre-pandemic levels is not a signal that they are about to burst.

Some economists are predicting a wages boom as a result of shortages of skills.

As an aside, in Australia, the business bosses are all screaming that the borders have to reopen because there is a skill shortage emerging and they cannot get enough workers.

What they are really saying but won’t is that for too long they have been exploiting cheap, non-unionised labour – short-term foreign (guest worker type) visas or backpackers on holiday – to get labour and avoid paying the statutory wages and providing legal minimum conditions.

So, of course, with the borders shut at present, that source of labour has gone.

But there is still 13.5 per cent of workers not working in one way or another (unemployment or underemployment) and all these bosses need to do is pay the legal wages and they will be able to attract those workers back into employment.

When they scream skill shortage, they are really saying they are not prepared to pay the going wage for workers who are currently available and seeking work.

Scum.

But back to the Bank of England.

It seems that the most recent governor (Andrew Bailey) doesn’t agree with Haldane on the inflation threat.

He predicts some “temporary” price pressures and that:

… the really big question is, is … [whether rising inflation is] … going to persist or not? Our view is that on the basis of what we’re seeing so far, we don’t think it is.

I share that view.

If you look at the underlying data an large scale inflationary event can really only occur if output gaps are eliminated and the economy is maintained at very high pressure for an extended period and/or if raw material prices rise and firms and workers have the capacity to defend their real margins/wages in a time of low relative productivity growth.

At present those sorts of conditions do not appear to be present.

I am yet to see unemployment reach the low levels that would be consistent with a massive wages push from workers.

And what we learned in the period since the 1991 recession is that while unemployment eventually fell to lower levels (never reaching full employment), the labour market slack was maintained by rising underemployment.

The rise of underemployment accompanying the casualisation of the labour market in the neo-liberal era, means that ‘within-firm’ measures of labour slack were now an additional way in which wages growth is suppressed.

I wrote about that in this blog post among others – Not only smokeless, but looking rusty and unusable (October 28, 2010).

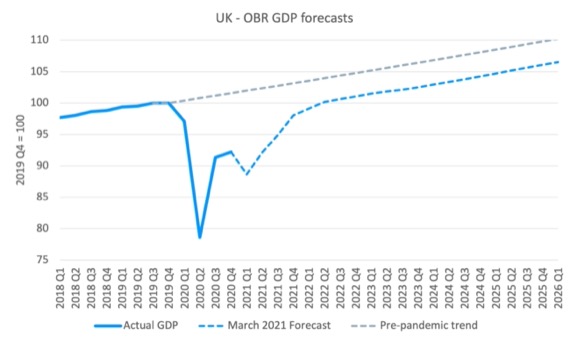

The British Office of Budget Responsibility clearly doesn’t think that GDP growth is about to bounce back into double digits.

In its – Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2021 – it predicted that by first-quarter 2026, GDP would only be 6.5 per cent above its March 2020 level.

That is well below the level that would have been achieved if the pandemic had not occurred and GDP had have grown on its pre-pandemic trend.

In that case, GDP would be 10.2 per cent above its March 2020 level by March 2026.

Hardly the stuff that ignites a spending led inflationary spiral.

I produced this graph from their supplementary data set.

But what about potential GDP?

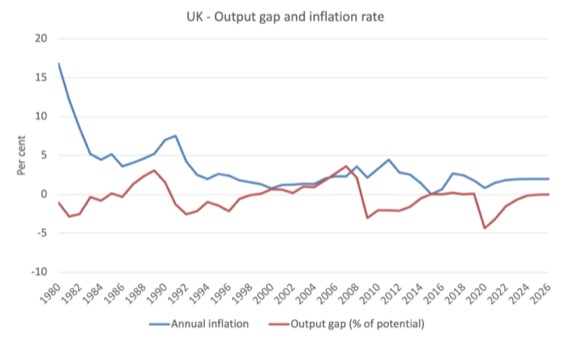

The following graph shows the IMF’s WEO measures of the British output gap (as a percentage of potential output) and the annual inflation rate from 1980 to the IMF’s current forecast horizon of 2026.

The output gap measures how far actual real GDP deviates from potential GDP.

Regular readers will know that I consider the output gap measures produced by organisations such as the IMF (and OBR, for that matter) are biased downwards – that is, they estimate smaller output gaps than exist in reality.

Please read the following blog post for more information on that – The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

So, if anything the IMF measure, that is used by many to assess how strong demand is relative to supply potential, will be biased towards the inflation mania narrative.

But examining the data suggests a different story.

First, the output gap remains open throughout the period of the forecast.

Second, if you try to tell an inflation narrative based on ‘too much money chasing too few goods’ (that is, using the output gap measure to indicate spending pressure), then you won’t get very far.

And note that in 1999 and 2008, the IMF was estimating the output gap to be positive. The gap in 2005 was estimated to be 1.784 per cent, then 2.687 per cent, then 3.612 per cent, then in 2008 2.164 percent.

The meaning of a positive output gap is that actual output is outstripping productive capacity, which if true would definitely mean an overheating economy – especially when the state was being maintained for 8 years or so.

During the latter part of that period, the unemployment rate was 4.825 per cent (2005), 5.425 per cent (2006), 5.35 per cent (2007) and 5.725 per cent (2008) – hardly a signal that the economy was overheating.

And between 1999 and 2007, the inflation rate rose from 1.3 per cent to 2.3 per cent, hardly an acceleration.

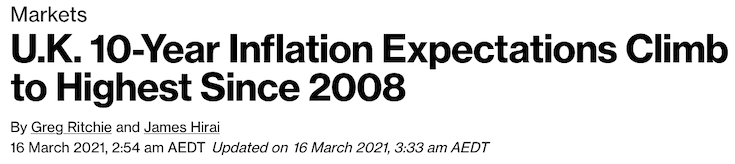

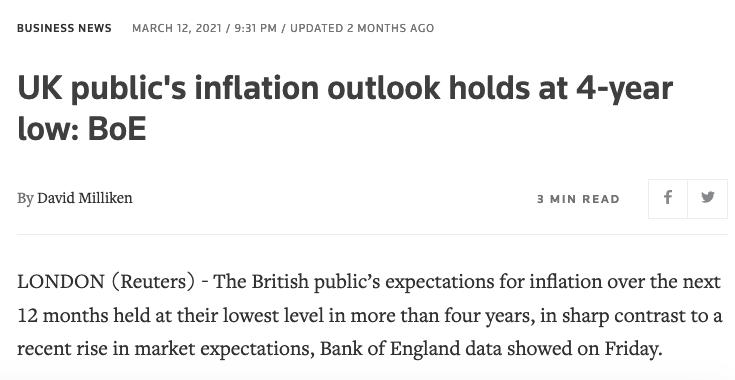

And to see the sort of bias in reporting consider these two headlines which were published about the same data release.

Bloomberg beating up the inflation mania.

Reuters reporting it as it is.

And when the ONS released the latest data – Consumer price inflation, UK: March 2021 – we learned that:

1. The March 2021 CPI index rose to 109.7 from 109.4 in February 2021.

2. The 12-month inflation rate was 1 per cent to March 2021 and the one-month shift in March was 0.2 per cent.

3. You will be disappointed by the data if you have bought into the inflation mania stuff.

Conclusion

Clearly, some areas of our economies will experience price pressures in the coming period given the disruptions in supply and various administrative pricing decisions by governments (reversing pandemic assistance in areas like rents, energy, child care etc).

But these pressures in some segments of the economy are unlikely to instigate a major shift to high generalised inflation rates because the capacity of workers to defend their real wages is diminished now.

Fiscal policy has a long way to go yet in reducing unemployment and underemployment from their elevated levels before that capacity becomes functional again.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill – remember Pressure DRop from the 1970s. Good to see you are still playing. ( I am President of the Melbourne Blues Appreciation Society!).

Onto serious stuff, are you familiar with the writings of Adolph L Reed Jnr. Not necessarily economics but touches on some of the same issues. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolph_L._Reed_Jr

The role of technology in the economy seems to be totally overlooked. There will be a disenfranchised class due to the introduction of the new technologies. We have to look after them.

Keep up the good work.

Best Regards

John

Could there be significant inflation from a rising profit share, as businesses can finally get away with putting up their prices?

The avalanche of inflation scare stories in the press causes me to wonder whether or not journalists are being bonused for every mention of it?

Bill wrote,”Last week, the outgoing Bank of England chief economist (Andy Haldane) claimed that

. . . . [Is there something missing here?]

I note that this is not the scenario that the Bank of England predicted in 2016 in the lead up and aftermath of the Brexit referendum.”

Interesting topic. I consider inflation fear-mongering in the news to be positive – it is going to support consumption/spending, that would be subdued otherwise.

“as businesses can finally get away with putting up their prices?”

Given the level of unemployment and underemployment won’t that just attract competitors?

Slightly tongue in cheek I’ve been using the following line:

“Inflation is always and everywhere a lack of competition. Price rises attract their own supply.”

Given a quantity expanding firm will always outcompete a price expanding firm, then price rises can only stick in an oligopolistic environment.

Re: ‘price pressures …given … various administrative pricing decisions by governments’, the most obvious of these in the UK being the support for very discriminatory house price inflation. I think the other day I heard the Business Secretary (though it might have been another of the govt.’s talking heads) coming out with the ‘do whatever it takes’ line on supporting businesses. Clearly he meant do whatever it takes to support the income stream of banks and landlords.

More off-topic, I think I heard a commentator or Japanese govt. spokesman say that the Olympic Games had to go ahead to give the people something for the enormous cost. I don’t know what the financing arrangements are, whether it’s from a municipal authority not properly supported by the currency issuing government or by the currency issuing government itself, but it struck me that the construction workers and material suppliers must have all been paid off as work was done. The future economic cost of cancellation would be comparatively small, there might even be a bonus in clearing up. Same with HS2 (UK high-speed line between London and Brum.) and the clear-up of its envoronmental destruction.

A few weeks ago the press in Canada were telling us that a large portion of the Canadian population were near bankruptcy (within $200 of that) due to the pandemic conditions and things were generally looking grim for the economy. Now, however, all we have been hearing is how we are about to experience two years of rapid growth and price inflation.

All of this comes via mainstream media and the sources are generally economists employed by big banks.

As the story goes, it’s small businesses who will drive this inflation; with polling apparently showing many small businesses intend to “raise their prices to make up for losses” experienced during the periods of restricted economic activity. The ones who have managed to survive the pandemic that is.

The effects of having fewer temporary foreign workers around due to travel restrictions might be felt when the spring harvests arrive. Perhaps we will start doing what we used to do, and pay unemployed young people a decent wage for such work?

Is all the hype about inflation we are now hearing a smokescreen to cover over the failures of neo liberal ideals being exposed, wishful thinking, or is it just the mainstream economists taking a gamble just in case prices do actually rise, so they could then say see we were right all along?

Sorry to be “that guy”, but Michael Fish made his infamous announcement about the storms that hit the UK on October 15th 1987, not “in October 15”.

” with polling apparently showing many small businesses intend to “raise their prices to make up for losses””

Did they bother explaining how they intend to do that in a competitive market?

If in 2004-08 the scare tactic was the debt and the need for austerity, now it will be inflation. I have seen finance people talk of Weimar and possible hyperinflation. This will be the argument for small government and no fiscal intervention from Govs. So I expect a revisit of this blog. Sigh. Plus ca change…

Why is inflation always the bugaboo, instead of unemployment/underemployment, affordable housing, food insecurity, health insurance (in the U.S.), environmental health, quality of life in general, not to speak of massive military spending? Our fears are mirrors, are they not?

No they didn’t take competition into account at all, in fact there was little by way of analysis, you know mainstream media, no one questions; however, I think there has also been some attrition in the small businesses world during the lock downs, so there are likely fewer competitors than existed prior. Unfortunately, there were also a few taking gambles on launching a small business on speculation the vaccines would bring a quick return to normal.

Doing the opposite of what they say may not be a bad way to start. =)

Hi Newton, in response to your question “Why is inflation always the bugaboo, instead of unemployment… etc” I think the answer might lie in the fact that inflation devalues the wealth of the upper classes of our societies. It also affects the middle and working class negatively, but not to the extent that it affects institutional investors etcetera. It is a pity that our priorities as a society have been so entirely infected by the values of the ultra-wealthy. We need a more holistic set of values, like some of the things you mention; quality of life, affordable housing, employment levels, and more equitable societies.

Reply to @Gabriel and @’Newton E. Finn’

Strictly speaking inflation does nothing at all to devalue real wealth of the upper class. It lowers the purchasing power of their hoarded *cash*. If they’ve banked at a decent interest rate inflation will not do much to devalue the purchasing power of their *savings* accounts.

Inflation is at worst a “war on cash” but that’s as it should be. The tax credit is not really supposed to be for hoarding, it’s for spending.

The possible exception is real estate: but rising house prices are not rising real wealth, it’s a ponzi bidding process fueled by bank credit extension for non-productive speculation. Your actual house is more likely depreciating in real value. So if you lose a bit on nominal house value thanks to relative deflation of real estate relative to other prices, you are probably still winning comparative to real exchange/use value, thanks to Mr Ponzi and the banks. Meanwhile the homeless are perennially losing.

@Bijou, of course real estate (land) is real wealth – you can’t do anything without land. “Buy land, they’re not making any more of it”.