Last Friday (December 5, 2025), I filmed an extended discussion with my Kyoto University colleague,…

Not only smokeless, but looking rusty and unusable

When does the word down mean down? Answer for all of us mortal folks: when something is consistently pointing downwards. Answer for the bank economists: never when it is applied to movements in the Consumer Price Index – down means up. The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the Consumer Price Index, Australia data for the September 2010 quarter yesterday and it showed that inflation is moderate and falling. Over the last week, the bank economists ran their usual line – they were predicting spikes in the inflation rate and thus the absolute necessity for increasing interest rates at the next RBA meeting. As usual they were wrong. The reality is that the Australian economy is not overheating and it is still a long way from being at full capacity. Some sectors are growing strongly (mining) but that unlikely to create significant cost pressures elsewhere in the economy given the amount of labour slack. I have a tip for the bank economists. They should come out next month/quarter and say exactly the opposite to what they typically would say – and they will probably get it right. At least while they are worrying themselves sick about the course of inflation they are not screaming about the deficit being too big.

The “inflationists” started trembling early this week. Last Monday (October 25, 2010) the ABS had released the latest Producer Price Index data which showed an annual growth of 2.2 per cent for September 2010. This was up from the previous four quarters (two of which had recorded negative growth) but still well below the growth recorded just before the crisis.

The release provoked a chorus of bank economists desperately trying to predict the highest inflation forecast for yesterday’s CPI release. These characters nearly choke trying to fit all the scare words into one sentence – overheating, overblown, rates will rise, and all that jive. As I noted in the introduction they are usually always wrong and even the most dim-witted living organisms have internal feedback mechanisms that allow them to error correct.

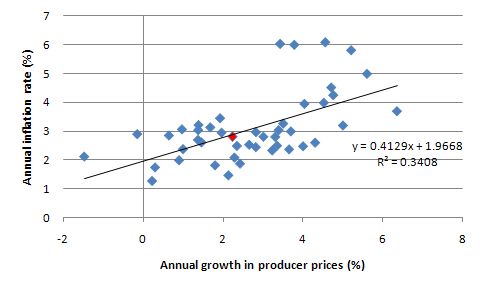

On Monday afternoon I ran some regressions examining the relationship between the annual growth in producer prices and consumer prices. The following graph shows you the relationship with the former on the horizontal axis and the latter on the vertical axis. The red marker is the September 2010 quarter.

The black line is a simple regression (which ended up just as good as more complex ARMA type configurations – for those who know about time series modelling). You can see the September quarter is right on the line. The regression forecast for the one-period ahead out of sample CPI growth was 2.9 per cent. The actual result yesterday was 2.8 per cent. So I was unnecessarily worried ! (-:

The fact is that there are no obvious signs that consumer prices are about to break out in any dangerous fashion at present.

Apparently, members of my profession were engaging in some esoteric breathing exercises yesterday prior to 11.30. My source of that information comes from our national broadcaster’s news service which carried the headline – Economists hold breath for inflation figures. The story confirmed the view I have that we have reached a most ridiculous state in public policy where we entrust major macroeconomic settings to an unelected and largely unaccountable arm of government – the central bank monetary policy board.

The ABC news story (released prior to the Australian Bureau of Statistics inflation data release yesterday) said:

Economists expect that fresh inflation figures due out today will be in the Reserve Bank’s 2-3 per cent comfort zone, but a rate rise is still on the cards. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) figures are tipped to show core inflation fell to around 2.6 per cent.

Then some bank economist was quoted as saying that the RBA will lift rates in the coming month:

…. because it wants to keep a lid on inflation … [and we have an economy that is] … growing currently … [at] … around 3 per cent … and there are … [price pressures] … in Western Australia, which I think are eventually going to spread.

The talk is of the “we know is coming for the economy” given the strong expected investment boom in the mining sector”. This will be “very inflationary and needs to be managed with higher interest rates now”.

Another bank economist said:

We think they need to be ahead of this. If they risk waiting … they risk having to do more.

If you think about this for a moment you will realise how absurd the argument is. Remember, these economists actually believe that monetary policy is very effective in disciplining aggregate demand whereas I consider it to be uncertain in impact, subject to unknown lags, and incapable of being targetted. That is, I think it is a very unsuitable policy tool for performing the job that it currently being used for.

But the bank economists must therefore want to choke off aggregate demand before it even arises. That is, they want to stifle the investment boom that might or might not occur in the coming years.

Upon what basis is that deemed to be sensible policy? Answer: this lot consider we are already at full capacity.

Reality check: we have at least 12.5 per cent of our willing labour resources idle (either unemployed or underemployed). That is a lot of slack to be absorbed.

Would the better policy option be to ensure that this labour is able to participate in the investment boom as it unfolds (if it does!)? By maintaining a tight policy framework when inflation is actually falling just because we might have an investment boom in the future is ridiculous.

The government can choke off aggregate demand sometime down the track in a much more direct, targetted and certain way via fiscal policy. The bankers will scream – but the government is politically trapped and cannot easily increase taxes/reduce spending.

My preference – as a citizen in a supposed democracy – is to continually be proposing policy measures that allow that democracy to work rather than subjugating it. If the government is incapable of using fiscal policy at some point in the future to discipline an inflation spike should this once-in-a-100 year investment boom actually evolve then they deserve to lose office and the economic data will provide us with appropriate signals.

But allowing the unelected and unaccountable central bank to do the dirty work – with their blunt tools which are incapable of targetting the damage of rising interest rates – at a time when households are still carrying record levels of indebtedness is one thing. That is, in my view an insult to our democracy.

But suggesting the central bank introduce hardship now when inflation is actually falling and significant increases in real growth are still required to eat into the pool of idle labour just because the investment boom might bring inflation pressures is a disgrace to our democracy.

The government should use their legislative powers to stop the RBA hiking rates in November! (-:

At least one bank economist has seen the absurdity of the banter – telling the Sydney Morning Herald that:

Reserve Bank staff have elegantly painted themselves into a corner … ‘The inflation figure leaves the rate gun not only smokeless, but looking rusty and unusable. Both the trajectory and the absolute level of inflation would make it a challenge to hike.

I quite liked that idea – the rusty and unusable inflation rate gun – that is, the obsession the bank economists seem to always have with inflation especially given we haven’t had an inflation problem (if you could call inflation a problem) since the late 1980s.

That’s 20 years folks – time to shed the anxiety although I note the Germans are still petrified of it some 85 years later. I have never been able to work out why we are so scared of inflation (given no-one dies from it) whereas our sensitivity to unemployment is much lower (and people do die from the poverty that joblessness brings).

Trends in inflation

The headline inflation rate increased by a relatively modest 0.7 per cent in the September quarter and this translates into an annualised increase of 2.8 per cent for the year to September down from 3.1 per cent.

The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term. So they claim to have a forward-looking agenda although exactly what that means is difficult to discern.

But they do not rely on the headline rate. Instead, they use two measures of underlying inflation which attempt to net out the most volatile price movements.

The special measures that the RBA uses as part of its deliberations each month about interest rate rises – the trimmed mean and the weighted median – also showed moderating price pressures.

The annual growth in the weighted median fell from 2.7 per cent in the June quarter to 2.3 per cent in the September quarter, while the trimmed mean fell from 2.7 per cent to 2.5 per cent over the same period.

The smoking gun just got rusty!

Given the Reserve Bank’s inflation target band is 2-3 per cent and all measures of inflation are falling at present (with underlying real unit labour costs also falling) I cannot see how anyone can forecast that there will be an interest rate hike next month.

The fact that I am even talking about the “possibility” is because the bank economists never let up and have (mis-)educated the public into believing inflation is about to burst out of control unless rates go up.

To understand this more fully, you might like to read the March 2010 RBA Bulletin which contains an interesting article – Measures of Underlying Inflation. That article explains the different inflation measures the RBA considers and the logic behind them.

The concept of underlying inflation is an attempt to separate the trend (“the persistent component of inflation) from the short-term fluctuations in prices. The main source of short-term “noise” comes from “fluctuations in commodity markets and agricultural conditions, policy changes, or seasonal or infrequent price resetting”.

The RBA uses several different measures of underlying inflation which are generally categorised as “exclusion-based measures” and “trimmed-mean measures”.

So, you can exclude “a particular set of volatile items – namely fruit, vegetables and automotive fuel” to get a better picture of the “persistent inflation pressures in the economy”. The main weaknesses with this method is that there can be “large temporary movements in components of the CPI that are not excluded” and volatile components can still be trending up (as in energy prices) or down.

The alternative trimmed-mean measures are popular among central bankers. The authors say:

The trimmed-mean rate of inflation is defined as the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away a certain percentage of the distribution of price changes at both ends of that distribution. These measures are calculated by ordering the seasonally adjusted price changes for all CPI components in any period from lowest to highest, trimming away those that lie at the two outer edges of the distribution of price changes for that period, and then calculating an average inflation rate from the remaining set of price changes.

So you get some measure of central tendency not by exclusion but by giving lower weighting to volatile elements. Two trimmed measures are used by the RBA: (a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

While the literature suggests that trimmed-mean estimates have “a higher signal-to-noise ratio than the CPI or some exclusion-based measures” they also “can be affected by the presence of expenditure items with very large weights in the CPI basket”.

The authors say that in the RBA’s forecasting models used “to explain inflation use some measure of underlying inflation (often 15 per cent trimmed-mean inflation) as the dependent variable”.

So what has been happening with these different measures?

The following graph shows the three main inflation series published by the ABS – the annual percentage change in the all items CPI (blue line); the annual changes in the weighted median (red line) and the trimmed mean (green line).

Remember the trimmed measures (weighted median and trimmed mean) are designed to depict tendency or trend and attempt to overcome misleading interpretations of trend derived from the actual series. They are all heading downwards.

My interpretation is that underlying inflation trend is downward and falling towards the lower end of the RBA target band. There is no inflationary threat in Australia at present.

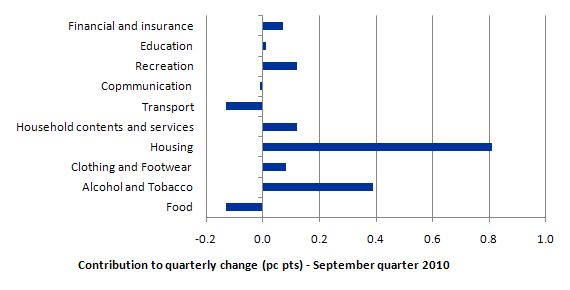

The following bar chart shows the contributions to the quarterly change in the CPI for the September 2010 quarter by component. The most significant price rises were for “tobacco (+7.0%), water and sewerage (+12.8%), electricity (+6.0%), property rates and charges (+6.2%) and rents (+1.1%)”.

Does government charges ring a bell? If you are trying to find evidence of demand pull factors you will be disappointed.

The ABS reports that the “most significant offsetting price falls were for automotive fuel (-3.7%), vegetables (-5.4%), pharmaceuticals (-3.9%), audio, visual and computing equipment (-2.7%) and soft drinks, waters and juices (-1.8%).” These factors are better indicators of the state of aggregate demand and the conclusion is that there is not an overheating product market.

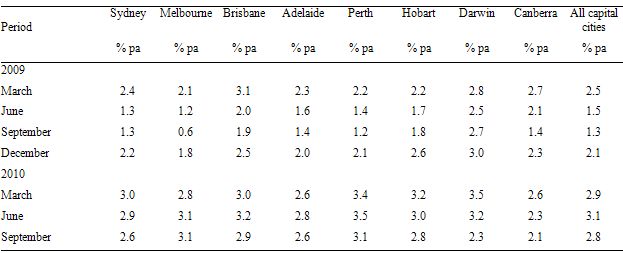

You will note that one of the bankers claimed that price pressures were building in Western Australia. Perth is the capital city of Western Australia so you would expect to see evidence of rising inflation there if the claim had any merit.

The following Table shows the annual inflation data for the Australian capital cities since March 2009. The data is from the ABS. The impact of the crisis in 2009 is clear as is the early recovery period in the first two quarters of 2010 when price inflation in the capital cities returned to normal levels (with some disparities).

Perth, Brisbane and Darwin are the capital cities in the mining states which are currently enjoying good commodity prices and strong demand. I can only see inflation moderating these cities in the September quarter.

Shifting relations between labour underutilisation and inflation

Some years ago (2004) I wrote a paper which explored the notion that a declining unemployment rate no longer provided the same signals for inflation trends as it might have done in the past. Specifically,I hypothesised that with the rise of underemployment accompanying the casualisation of the labour market in the neo-liberal era, “within-firm” measures of labour slack were now likely to be an additional way in which wages growth was suppressed.

In other words, you had to consider the broader measures of labour underutilisation in a study of inflation. These ideas coincided with the development of my broader hours-based measures of labour underutilisation which are now published as the CofFEE Labour Market Indicators.

Recall that the Phillips curve links the unemployment rate and inflation based upon the notion that unemployment is an inverse proxy for labour market pressure – so excess labour supply was considered to be a key variable constraining wage and price changes.

However, if the way in which the labour market slack manifests changes – to include slack within the firm (underemployment) as well as slack that is external to the firm (unemployment) – then the earlier approach to studying the Phillips curve will miss out on important factors that may help to explain inflation.

Specifically, a falling unemployment rate may be offset (to some degree) by rising underemployment. As a consequence, if the policy makers are attempting to gauge inflation pressure by examining movements in the unemployment rate (that is, the NAIRU type approach) they will overestimate the tightness of the labour market when there is signficiant underemployment.

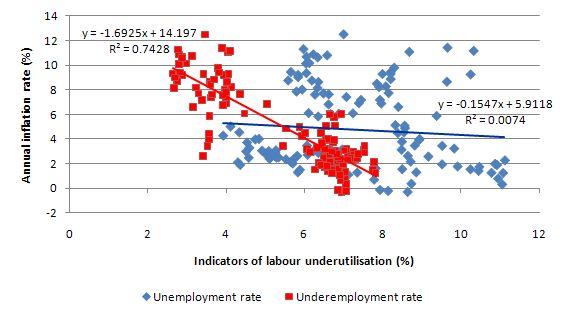

The following graph uses ABS data to plot the unemployment rate (%) on horizontal axis and the annual inflation rate (%) on the vertical axis. This is the conventional Phillips curve relationship. The black line and related statistics denote the simple linear regression.

The reality is that the surface has shifted a lot with the curve shifting out during the 1991 recession and back again during the growth period. All the instability in the relationship is driven by variations in the business cycle rather than reflecting inherent structural rigidities (and resolutions) a la the supply-side mantra.

I have written about this a lot. Please read my blogs – Nobel prize – hardly noble – The structural mismatch propaganda is spreading … again! – for more discussion on this point.

The point is that over the period shown (March 1979 to September 2010) the relationship between inflation and unemployment has been unstable and during the periods of stability it has been fairly flat – implying disinflation policies are very costly. Please read my blog – Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy – for more discussion of the sacrifice ratios involved in using unemployment to discipline inflation.

The next graph adds the ABS underemployment measure (red markers) to the unemployment rate data (blue markers). The coloured regression lines show the relationship between the relevant measure of labour underutilisation and annual inflation (on vertical axis). It is clear that inflation is more closely and stably related to underemployment than unemployment over this sample. The relationship is also statistically stronger.

While I do not hold out these simple regressions as being anything I would hang my professional hat on – the statistics show that if underemployment rises by one percentage point inflation falls by 1.69 percentage points. Whereas, for a one percentage point rise in the unemployment rate inflation falls by only 0.15 percentage points. That is, the relationship between underemployment and inflation is much steeper.

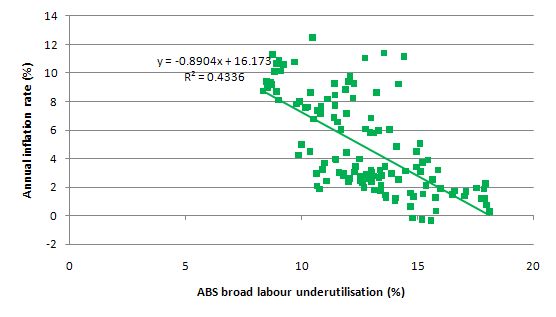

The final graph relates the ABS broad measure of labour underutilisation (unemployment plus underemployment) to inflation. This relationship reflects (averages) the different impacts on inflation from the components of labour underutilisation. It is clear that concentrating on the traditional Phillips curve relationship (between inflation and unemployment) is no longer appropriate. Analysts must consider the broader trends in the labour market before jumping onto their inflation horse.

In earlier work (2004) I tested several interesting testable hypotheses at that time about how the changing labour market impacted on the inflation generating process.

First, the standard Phillips curve model predicts a significant negative coefficient on the official unemployment rate (a proxy for excess demand). I found that in the sample tested (February 1978 to September 2004), the unemployment rate in a typical Phillips curve model exerted a statistically-significant negative influence on the rate of inflation.

Second, when I added an underemployment variable I found it exerts negative influence on annual inflation with the negative impact of the UR being reduced.

Third, I also found that movements in short-term unemployment are more important for disciplining inflation than unemployment overall. This result was consistent with the hysteresis model which suggests that state dependence is positively related to unemployment duration and at some point the long-term unemployed cease to exert any threat to those currently employed.

This suggests that a downturn, which increases short-term unemployment sharply, reduces inflation because the inflow into short-term unemployment is comprised of those currently employed and active in wage bargaining processes. In a prolonged downturn, average duration of unemployment rises and the pressure exerted on the wage setting system by unemployment overall falls.

This requires higher levels of short-term unemployment being created to reach low inflation targets with the consequence of increasing proportions of long-term unemployment being created. In addition, as real GDP growth moderates and falls, underemployment also increases placing further constraint on price inflation.

There were other results but I will talk about them more when I write about our latest work in this area (sometime later in the year).

I will have more detailed (academic) work done on the revisions to the Phillips curve in a few months. At the upcoming CofFEE conference in December, Joan Muysken and I will present our latest research on this question which comprises an analytical model which allows us to understand the way in which inflation is now disciplined in the labour market – both external to firms (via unemployment) and internal to firms (via underemployment).

The point is that even though unemployment has fallen in Australia since the worst period of the recent downturn, underemployment has not falling much and rose sharply as the economy slowed. The inflation discipline coming from the labour market is at present fairly strong and that is why I conclude there is not significant inflation threat coming from that source.

Conclusion

What is obvious is that there is moderating inflation. It might surge in the future but then again it might not. When it starts showing signs – that is, there are several indicators all pointing to an overheating economy then policy makers should act.

But while inflation is falling and the other indicators are all showing considerable slack remains in the economy it is ridiculous to be advocating policy tightening.

Part of the problem is that the underlying labour market dynamics are not well understood by the neo-liberals and their models thus lead them into making erroneous predictions all the time.

I would be embarrassed right now if I was a deficit terrorist or an inflationist (the two usually go together). The data is continually going against their wild assertions. The world doesn’t look remotely like they said it would.

I realise that by continually predicting inflation spikes eventually you will proven correct. But what a pathetic way that is to proceed.

At present, I see a growing economy with a lot of labour market slack and uncertain aggregate demand conditions ahead. We still do not know what the impact of the by fiscal withdrawal will be and I see no inflation in sight coming from demand pull factors. There are indications that private investment will rise strongly in 2011. My advice – enjoy it while it lasts and make sure it absorbs the idle labour.

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill,

A bit off topic: it was just announced that the RBA will not be paying the government a dividend this year. As I understand MMT paying the government a dividend is just a wank anyway – or am I missing something?

Cheers

Graham

You ought to be giving McCrann a big serving along the way. His ridiculous ‘inside’ knowledge last month didn’t eventuate and yet against he reads things into the numbers and Governor’s words which the rest of us don’t see. No-one sweats on the monthly RBA outcome more than this guy and I’m a bit miffed how you let him get away with it.

” I have never been able to work out why we are so scared of inflation”

That’s probably because you don’t have a kings ransom tied up in government bonds.

Also, credit growth has not returned to pre-GFC levels and is moving roughly sideways at a rather lower level. When credit money is flowing through the economy at a significantly slower pace, that must create (assuming other things stay equal) something of a drag on consumer demand, I would think.

That one in eight unemployed or underemployed represents the reserve army of labour. According to theory, the bigger the reserve army, the lower the wage, the more profit is made. So in theory the number of unemployed or underemployed can never be too big. This is mainly achieved in a different way, by longevity producing an ever lower activity ratio (until the politicians wise up and increase the retirement age).

An interesting scenario is beginning to unfold in Western economies, in which the population is living forever longer, but is only competitive in the gloabl labour market until its mid-forties, after which it ceases to gain experience which makes it more valuable than younger workers, whilst declining from its physical (and indeed psychological as far as work is concerned) peak.

The legalisation of euthanasia is to to-day’s political agenda what the legalisation of abortion was two generations ago. The latter (together with easily available effective contraception) enabled a degree of labour market planning, whilst the former is becoming imperative to keep the dependency ratio within bounds.

Other way round innit? Weak consumer demand manifests as weak demand for credit (and retail sales). The underemployment rate seems to describe why we have these ‘domestic’ demand variables running at a (low) pace that wouldn’t normally accord with a 5.1% headline unemployment rate.

WRT ‘Inflation’ Bill provides THE BEST observations and analysis in the second video segment posted in his blog from yesterday. He starts at just a few seconds before the 16:00 mark in that second video. The general inflation discusssion starts at about 13:00.

Resp,

Weaker demand for credit for new housing and other construction equalls a lot less money flowing into the building sector and from there onto the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, bunnings, harvey norman, the brothel etc. Pretty sure we’ve had much higher credit demand previously at roughly the same rates of unemployment and underemployment.

While the expansion of the money supply by bank lending ultimately nets to zero extra fincial assets, in the short term that money surely runs through the economy, helping push consumer demand.

Can it work both ways?

Lefty,

“that money surely runs” : I respectfully would point out that you are applying physical performance characteristics to accounting.

Resp,

Actually, the unemployment/underemployment gap is pretty large large right now is it not? Larger than usual.

What do y’all make of this?

http://bs.doshisha.ac.jp/download/files/activity10/discussion/DBS-10-01.pdf

Er, ok Matt – what should I say instead? The financial assets are accounted for multiple times?

But what do you think? As far as I can see, bank lending is – in the short term at least – having a similar effect on demand as government deficit spending. Granted that if I borrow hundreds of thousands of dollars, I have to reduce my consumption over the term of the loan (assuming things remain equal) to pay it pack, but the hundreds of thousands of dollars in credit money the bank created with the loan hits the shops NOW as the immediate recipients of that money no doubt spend plenty of it on consumption.

The degree to which that credit money bolsters general consumer demand must be fairly dependent (not the only factor of course) on the rate at which such money is entering the economy, and a good example would probably be the number of new dwellings being constructed and their market price.

Obviously, apj is correct that weaker consumer demand weakens the demand for consumer credit but demand for a different type of credit – housing – is something else again.

It just seems logical to me that you do not necessarily have to have a high demand for flat-screen t.vs to have a high demand for housing, but a high demand for (ridiculously overvalued) housing creates a short-term flood (sorry, physical properties again) of demand for flat screen t.vs – or at least adds to it.

Innocent Abroad,I presume you will be volunteering for early euthanasia as you are so public spirited.

Lefty,

“While the expansion of the money supply by bank lending ultimately nets to zero extra fincial assets, in the short term that money surely runs through the economy, helping push consumer demand.”

You ultimately see that it is consumer demand that matters here and you are right on, but I would submit that it isn’t “money” that “pushes” demand. The demand is what is important, it looks to me that ‘measures of money’ are really just accounting for the transactions that result from the exercise of consumer demand via a line of credit of some sort or CB activity. Demand comes first, then the accounting.

Larger Issue wrt verbs:

We fight the “household” analogy in that many folks are confused and apply the same authorities to a govt sector that is running a FFNC regime as they apply to a household in that this is what they are most familiar with….this is very frustrating.

Accordingly, in a similar misconception, I also see an analogy that folks (and btw not necessarily you) make between measures of “money” or an economy and the Ideal Gas Equation from thermodynamics:

P x V = m x R x T

Pressure x Volume = mass of substance x Gas Constant x Temperature

It’s like they think economic policy can be conducted like a stovetop pressure cooker where increasing the “money supply” would be like increasing the temperature on the burner, thus increasing pressure for a constant volume…. or in a balloon analogy, “inflating” the balloon (increasing pressure and volume) by “injecting” mass.

I think this may be the basis for the actual economic terminology. You hear words used like: inflation, deflation, injection, pressure, driven, running, build-up, overheating, cool-down, liquidity, imbalance, leakage, I could go on… all of these are straight from Thermo/Fluids Science and it is wrong imo to use them in economics. Economics to me is a social science, not physical. You know, even Dow Chemical is running advertisements in the US that are saying it is the ‘human element’ that is the most important. We de-humanize the topic when we choose to use these terms.

Maybe economics needs it’s own lexicon.

I dont know how else to state this, other than just to say that it is misleading to think of an economy in these terms. These terms and principles just dont apply to economics and accounting…it’s deceptive. We have to be smarter than this.

Resp,

One doesn’t have to postulate ignorance on the part of the bank economists. Just self interest. As Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his job depends on not understanding it.” They are employed by the banks, probably with fat bonus/share packages, and the banks will make bigger profits if they can hike their rates. I agree with the ACCC: this “inflation hysteria” is actually price signalling in an oligopolistic market.

Matt: Maybe economics needs it’s own lexicon.

What economics needs is better explanations and analogies to explain complex economic concepts to non-economists, like politicians, the media, and the public. Many economists use conventional terminology that confuses the issues, even though when pressed they may admit that their words aren’t really begin used as most people would understand them.

Hi Matt.

Unlike most who frequent this blog, I have no formal education beyond high school. The bulk of what I understand about economics I learned from Bill in the earlier days of this blog. I have investigated other schools of thought and have concluded that Modern Monetary Theory is the correct way of understanding the core functioning of modern economies.

My original post was poorly worded, lacking context and I did not explain my thoughts clearly.

Just as an injection of government spending into the economy – for example, the two “cash splashes” the Australian government made by crediting millions of consumers bank accounts – created an undeniable surge in consumer spending (contrary to the claims of local Austrian thinkers who argued that it would have no such effect but would instead simply cause serious inflation if I recall correctly), the credit money created in response to demand for (ridiculously overvalued) housing cannot help but create a spending multiplier, unless somehow it is all saved. Demand for new housing must create more consumer demand downstream, to some extent.

Total demand for credit of all types is well down, including housing. Housing credit growth is no longer underpinning consumer demand to the same extent. Under these circumstances, I would been surprised to see any real inflation overall, barring an oil shock or something. When you’re having a roaring boom in real estate, I can’t see how that cannot be a positive influence on consumer demand.

So I’m not arguing that credit creation preceeds demand for credit, merely that credit created for one thing (new housing and construction) flows onto to another thing (consumer demand). Unless the credit money created somehow evaporates when it hits construction workers pockets instead of being spent again and again before sooner or later leaking away.

that’s also true, Lefty

Tom,

I dont know if there are analogies, I hate to say it, but maybe zanon is right, its the Academy.

The IT industry didnt have to make the public understand why Y2K may have been a problem, they just addressed whatever there was of the issue and got thru it and even made some money doing it…civil engineers dont have to make the public understand why they can fearlessly drive over a bridge. Air Travel, surgeries, PCs and OSs, elevators, autos, etc no else has this problem where the public has to “understand it”. Is this because there is a general mistrsust of the the govt/maintream economics? maybe the public at least can smell a rat?

I believe the mainstream practitioners in this social science, perhaps because it is so close/intertwined to government (100% corrupt), are spiritually corrupted. It takes a tremendously just person to not get caught up in it. Right now it looks to me like the only way to deal with it is to put the best people in govt/policy positions….and they wont even let someone like Warren get in the debate.

We are up against a lot, but I still feel motivated to inform/educate people I come across about the economic realities to the best of my ability.

Resp,

Matt Franko:

I love your excellent breakdown of the thermodynamics analogy. It’s heavily implied, and when you think about it, suddenly illuminates why the “printing money” = inflation idea is so ingrained.

I’ve always believed that we understand abstract ideas with physical analogies. When I do algebra I always imagine physically moving terms around, for example. Maybe that’s just me but I think a lot of things are imagined that way. Perhaps that’s why quantum mechanics and special relativity are so hard to get – there is little in the way of physical analogies. I guess that’s why your idea appeals to me.

“You hear words used like: inflation, deflation, injection, pressure, driven, running, build-up, overheating, cool-down, liquidity, imbalance, leakage, I could go on… all of these are straight from Thermo/Fluids Science and it is wrong imo to use them in economics.”

Respectfully Matt, I must disagree.

I understand what you say (I think) – I see the thing we choose to call “money” (or in this part of the world, I should more accurately call “Australian denominated financial assets”) as essentially an abstract concept, not a physical thing as such. It does exist, but not in the normal, physical sense. Warren Mosler’s “points in a game of ten pin bowling” is exactly how I think of it.

You are obviously mathematically-minded (I am not particularly) – but we need to bear in mind that most of the population are not particularly this way inclined either. Algebra and thermo fluid dynamics mean little or nothing to most people. I understand that in most monetary transactions, nothing has physically moved or flowed as such – but try explaining that to the public at large.

If we wish MMT to be embraced by the public (and I most certainly do!) then it has to be presented to us in terms that we can readily understand. Grigory makes a good point about understanding abstractions with physical analogies. This is how most of us naturally think. It is easy for most of us to understand money as something that posesses physical properties – ie, it flows from point to point to point. I see no harm in thinking about it in such a fashion as long as we understand what it really is and where it really comes from – think of sovereign government as both creator and destroyer of money.

I respect that your understanding is deeper than this, but any attempt to explain these things in completely abstract, non-physical accounting type terms to most people is bound to fail.

Lefty,

#1, To me, you have more intelligence at this point than a Nobel prize “winner”, truly I believe this. And IMO youve got it wrt the demand side.

I take your and Grigory’s point that we may not be able to fully eliminate any physical analogies. Perhaps it is in our nature to ‘abstract’ (as the verb def.: 1. to think of (a quality or concept) generally without reference to a specific example) these kinds of economic concepts.

Maybe as long as we know the true human measures/outcomes of policies, we may be able to still work using these terms for convenience of thought.

But the next time you hear someone on TV/media in some self-righteous way say: “We’ve got to inject more liquidity!”, I hope you have a good laugh as I often do. I often think of the old Star Trek TV show here in US where the Engineer Mr Scott, no matter what the situation, keeps shouting to Captain Kirk that he “needs more power!”. .. “We need more liquidity!” LOL!

Resp,

Physical analogies are often misleading in the social sciences, where biological analogies are more apt. Many economists have physics envy and know little about the social and biological sciences, so it is not surprising that they would use analogies and terminology that mislead and result in confusion. It is also not surprising for people that have little regard for stock-flow consistency.

It is surprising for supposed scientists not to recognize the necessity for operational definition of technical terms and also to overlook the emphasis of Anglo-American philosophy over the past century on using linguistic analysis to clear up confusion resulting from imprecision. I guess the are either careless or don’t get out much.

Cheers Matt.

I’m not sure that a humble school janitor/groundskeeper is quite up to the amount of smarts posessed by a Nobel prize winner though, but I do try. You have to wonder if a certain Nobel prize winner really does understand the nature of modern money but the politics of his position prevents him from just coming out and saying it. Likewise, here in Oz, it seems difficult to believe that federal treasurer Wayne Swan really doesn’t understand that he is presiding over a modern monetary system that uses a floating, non-convertable fiat currency – and exactly what possibilites are open to government, of which he is one of the highest level members.

But politics dictate that he must not challenge the (mis)understanding of we, the electorate. To do so would be politcal suicide. To publicly announce that everything we thought we knew about the functioning of the economy was wrong, that a sovereign government budget does not function remotely like a household or business budget, that taxpayers fund nothing in reality, that government deficits are not something to be feared and “fixed” at all costs – I think the public would instantly reject a government making such an announcement as massively incompetent and punish them severely at the next election, forcing them to spend at least a decade in the political wilderness. So they feel pressured to pander to our deeply entrenched misconceptions and promise to return the budget to surplus as soon as possible.

This is the sort of thing we’re up against practically everywhere. I really hope Warren succeeds in his quest for a seante seat in the US – that would potentially be a great step in disseminating the truth to the public.

“I often think of the old Star Trek TV show here in US where the Engineer Mr Scott, no matter what the situation, keeps shouting to Captain Kirk that he “needs more power!”. .. “We need more liquidity!” LOL!”

Yep, I vaugely remember the old series with Captain Kirk (I’m not quite a trekkie but I used to watch the next generation series with Patrick Stewart as Captain Picard), and if I were in a position to advise the Tory government in the UK about the direction they are taking the economy, I would probably use another favourite Scotty qoute: ” She canna take much more of this captain – she’s a gonna break up!”

cheers mate.

“I have never been able to work out why we are so scared of inflation (given no-one dies from it) whereas our sensitivity to unemployment is much lower (and people do die from the poverty that joblessness brings).”

I agree that the fear of potential future inflation is more than overblown. However, don’t people die from hyper-inflation, when their life savings evaporate?

Tom Hickey: “Physical analogies are often misleading in the social sciences, where biological analogies are more apt. Many economists have physics envy and know little about the social and biological sciences, so it is not surprising that they would use analogies and terminology that mislead and result in confusion. It is also not surprising for people that have little regard for stock-flow consistency.”

Well, identities are like conservation laws, which are the staple of physics. 🙂

Tom Hickey: “It is surprising for supposed scientists not to recognize the necessity for operational definition of technical terms”

But that would be empirical. There are limits, after all. 😉

Tom Hickey: “and also to overlook the emphasis of Anglo-American philosophy over the past century on using linguistic analysis to clear up confusion resulting from imprecision.”

But that would mean admitting that a great deal of economic terminology is value laden. We can’t have that. 😉

This is what I was alluding to in my first post on this thread (though I was referring to Australia there, this one is for the US).

Residential investment in the US has declined to a new low as a % of GDP.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2010/10/residential-investment-declines-to-new.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+CalculatedRisk+%28Calculated+Risk%29

Given that residential investment must surely make a significant contribution to consumer demand through the spending multiplier, the housing sector must be acting as a drag on consumer spending. Not only is the sector itself not experiencing employment growth, it can’t be contributing to broad consumer demand but is subtracting from it – historically, it should be making a positive contribution to employment across the US economy by now as the investment spending fuelled by credit growth “flows” out into other sectors, but is making a negative one instead.

I’m aware that private consumption supposedly grew reasonably strongly in the third quater – but real final demand was a weak 0.6%, which probably says something about the components that make up what is considered to be private consumption in the GDP data.

I may be wrong, but it seems intuitive to me that while the housing sector continues to decline/stagnate, the US is going to need a pretty significant sized alternative economic driver to restore the country to health.

As we know, the US government can always provide this but the question is: will they?

dunno about you Lefty, but I’ve been noticing an increasing amount of articles/media on the subject of fiscal policy lately (and increasingly from Bernanke too! as as the CBO etc etc), so it looks like the US will go down that road at some point, even if it is as a result of a bargain with the greedy Republicans to maintain their increasing share of the economic pie post-election. In other words, the Obama (gee I had high hopes) Administration might not get the mix right yet again. But something is better than nothing, and increasing unemployment benefits past 99 weeks will surely have to also be increased as part of the bargain.

I think reality has to assert itself eventually apj. No matter how ideologically opposed the powers that be are, active fiscal policy is the only way out of the mess. Many people have commented that the US public believes fiscal stimulus to be a failure. Even thought they are angry at the corporate bailouts, they conflate TARP with stimulus and arrive at a stimulus spending figure far greater than it actually was and look around and see still high unemployment, sluggish growth, falling house prices etc and logically conclude that it didn’t work. So the notion of fiscal stimulus has been politically tainted.

Here in Australia (you’re in the US aren’t you?) the fiscal stimulus was quite effective. Unemployment from an MMT perspective is of course far too high but the country successfully avoided recession and unemployment only rose a little over 1 percent before falling back again. Because it was generally a successful, neo-liberal sympathisers have run the most extrordinary scare campaign to discredit fiscal policy and the active involvment of government in the economy. The lies, hysteria, distortions – it’s both sickening and outrageous, designed to make it politically impossible for government to ever implement stimulus or be generally more active in the economy again.

But anyway, they say if you’re on the wrong track, you keep getting hit by little pebbles. Ignore the pebbles and you get slammed with a brick. Ignore the brick and you get wiped out by a boulder. Let’s hope our leaders take us down the correct path before it gets to the boulder stage.