My friend Alan Kohler, who is the finance presenter at the ABC, wrote an interesting…

Governments must restore the capacity to allow them to run large infrastructure projects effectively

One of the major complaints that Milton Friedman and his ilk made about the use of discretionary fiscal policy was that time lags made it ineffective and even dangerously inflationary. By the time the policy makers have worked out there is a problem and ground out the policy intervention, the problem has passed and the intervention then becomes unpredictable in consequence (and unnecessary anyway). The Financial Times article (March 29, 2021) – To compare the EU and US pandemic packages misses the point – written by Ireland’s finance minister reminded me of the Friedman debate in the 1960s. Apart from the fact that the article is highly misleading (aka spreading falsehoods), it actually exposes a major problem with the way the European Commission operates. If Friedman’s claim ever had any credibility, then, they would fairly accurately describe how the European Union deals with economic crises. Always too little, too late … and never particularly targetted at the problem. The debate remains relevant though as governments move away a strict reliance on monetary policy and realise that fiscal policy interventions are the only way forward. Most governments around the world are talking big on public infrastructure projects. However, the design of such interventions must be carefully considered because they can easily be dysfunctional. Further, thinking these projects are a replacement for short-term cash injections is also not advised. I consider these issues in this blog post.

On the FT article – it is just typical Europhile spin. Even at the depths of gloom, the officials are out there telling the world what a success the monetary union has been.

Their spin reminds me of this – Life of Brian – segment, where the EC is the Black Knight:

The point is that the European Union stimulus is yet to be fully implemented some 16 months after the crisis began. The bickering between Member States and the underlying resistance to allowing fiscal deficits to expand to the levels required has meant that when the spending finally flows, it will be too little and too late.

Needless suffering will be the legacy.

I cannot understand how any progressive thinker can continue to support this dysfunctional mess that is leaving millions of people unnecessarily in dire circumstances.

Big infrastructure spending plans

The new US President is trying to get a $US2 trillion infrastructure package – Public investment in infrastructure would be a much needed boon to the Australian economy – by Greg Jericho, shows that most of the jobs growth in Australia over the last year has been in public administration (particularly dealing with the pandemic), which shows how false the claim by conservatives that governments don’t create employment is.

He argues that there is a crying need for new projects covering “road, rail, bridges, telecommunication and sewerage” in Australia:

… while private investment remains down, the public sector needs to fill the hole …

He ties the need for public infrastructure spending to the need for a short-term boost to work.

Once again this gets us thinking about lags and whether public infrastructure projects are the best way to deal with a sudden collapse in employment.

Friedman on fiscal policy

On May 2, 2000, John B. Taylor from Stanford University conducted an – Interview with Milton Friedman – which was subsequently published in the journal, Macroeconomic Dynamics Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 101-131.

As an aside, he tells Taylor about his younger days and said:

I probably would have described myself as a socialist …

He apparently wrote an essay at the end of university which he stored away which described these views. Later in life, he tried to find it but couldn’t.

He said:

I’m pretty sure I did not have the views I later developed.

But the purpose of citing that Interview here is that Friedman was asked to reflect on his “two early articles on stabilization policy, the first one is on fiscal policy rules … and the second one focussed more on money growth rules …”

His first article (1948) outlined what was almost the orthodoxy at the time and is still professed by progressives who do not understand macroeconomics.

He said:

Rules for taxes and spending that would give budget balance on average but have deficits and surpluses over the cycle could automatically impart the right movement to the quantity of money.

By the time he wrote the second article (1968), he had shifted his position:

… you really didn’t need to worry too much about what was happening on the fiscal end, that you should concentrate on just keeping the money supply rising at a constant rate.

He claimed he now knew that “the link from fiscal policy to the economy was of no use.”

Taylor asked him to comment on the debate between Keynesians and the emerging Monetarists and he replied:

It’s over, everybody agrees fundamentally.

The academy shifted sharply in the late 1960s towards Friedman’s view.

The debate over ‘rules versus discretion’, which meant, on the one hand, that monetary policy rules were more reliable than relying on the discretion of the policy maker.

Friedman and Co. pointed to the so-called lags in policy that rendered interventions ineffective or dangerous.

They identified an overarching implementation lag – something bad happens but it takes time to recognise the issue and then administrative constraints delay the intervention.

By the time, the initiative, say an increase in government spending, is flowing, the issue has been resolved by the ‘market’ (private spending recovers) and the extra public spending becomes pro-cyclical and inflationary.

This lag is made up of two lags:

1. Recognition lag – detecting the problem.

2. Response lag – actually doing something about the problem.

So Friedman believed it was much better to have automatic rules that were beyond the daily discretion of policy makers that would sustain stable prices.

Of course, as soon as central banks started applying his fixed money supply growth rules (Bank of England first in the early 1970s) they found that they were actually not able to control the money supply as the mainstream textbooks claimed (and still do)

Lags in Infrastructure projects

In October 2020, the IMF published its – Fiscal Monitor – and – Chapter 2 Public Investment for the Recovery – contains some relevant analysis.

It notes that the immediate challenge of the pandemic was to “address the health emergency and provide lifelines for vulnerable households and businesses.”

That is, speedy and targetted cash injections were required.

But government should not abandon its responsibility, just because it has outlaid such amounts on temporary cash support, on facilitating:

… transformation to a post-pandemic economy that, with the right policies, can be more resilient, more inclusive, and greener.

In other words, fiscal policy design has to have temporal considerations – some tools are good for short-run, emergency stimulus, while other tools are better for achieving longer-term objectives.

Trying to mix these temporal characteristics runs the danger of falling into Friedman trap.

The IMF narratives about now is the time to engage in large-scale infrastructure spending by governments because interest rates are low is to be ignored.

These large-scale projects should be undertaken if there is a functional need identified which will deliver socio-economic benefits over a long period of time and transform economies towards the green future.

The idea that they are ‘cheaper’ for government when interest rates are low misconstrues what the ‘cost’ of the project actually is. It is the real resources that are used to complete the project, including those diverted and not available for other uses, that has to be considered.

The financial outlays are largely irrelevant.

The IMF is obsessed about “worsening debt dynamics” etc and “sovereign spreads” – which just goes to show they haven’t really made a transition across the line yet.

What they do get right though is recognising that:

With ample underused resources, public investment can also have a more powerful impact than in normal times.

The IMF try the ‘crowding out’ story which is another one of those myths.

But, clearly, as an economy approaches full capacity, the impact of increased spending on real output will decline and price adjustments will become the norm.

That is the constraint that has to be taken into account.

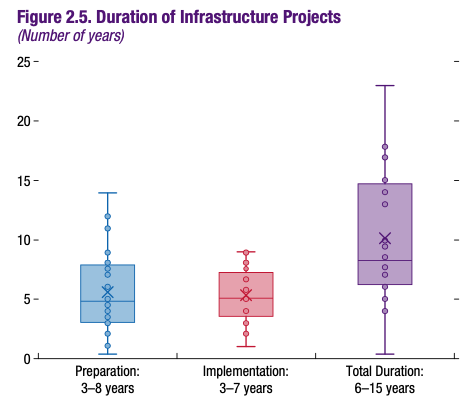

The Fiscal Monitor Chapter contains an interesting graphic – Figure 2.5 Duration of Infrastructure Projects – which I repeat here:

Why is that important?

It is important because it tells us:

1. These projects have long gestation periods.

2. They require government departments be forward thinking rather than reactive.

3. Years of eschewing ‘planning’, outsourcing out critical public functions to consultants, and privatisations, has undermined the capacity of governments to implement these type of projects in an effective manner.

4. A progressive agenda has to be to restore those capacities to the public sector as a matter of urgency.

The IMF note that:

… governments often hope to rely on “shovel-ready” projects that can be kick-started within a few months. Yet countries may find they have few such projects and thus may not be able to increase public investment in time to fight the current recession

And the reason for that is that under neoliberalism the capacity to plan and implement complex public policy interventions has been hollowed out by the move to convert public policy departments delivering services and infrastructure development into contract brokerage and management agencies.

The myopia of neoliberalism again on show.

The IMF lists four steps that:

… should be taken immediately: (1) focus on maintenance of existing infrastructure, (2) review and reprioritize active projects, (3) create and maintain a pipeline of projects that can be delivered within a couple of years, and (4) start planning for the new development priorities stemming from the crisis.

It is a bit rich of the IMF to now be telling governments this when they have been leading the charge in destroying these capacities in governments over the last several decades, particularly in less advanced nations.

There is a need for “smaller, shorter-duration projects” like maintenance, which can “be deployed quickly and has major economic benefits”.

Once again, it is a bit rich of the IMF to now admit that government spending can have “major economic benefits” after decades of demanding austerity and a run-down of capital spending by governments.

But, better late than never.

The crucial need for governments now and into the future is to restore their planning capacity – to take longer term positions so they can create a “pipeline of projects”.

The IMF say:

Governments should prepare a pipeline of carefully appraised projects that can be selected …

They talk about a 24 months time horizon, whereas I would be talking about a 20-year time outlook or longer.

It is clear that nations require long-lived public infrastructure – which means capacity which endures for decades rather than a few years.

Government planning can define this need, design appropriate scaled modules which sum to an entire nation-wide project and then accelerate or decelerate the spending and project implementation according to the state of the cycle.

That is the art of policy planning. To have projects that are conceived, designed, all the planning permits sorted out etc, which are then ‘shovel ready’ for relatively quick operationalisation.

Only then can we avoid the time lags that render these projects less suitable for rapid, counter-cyclical response.

While the infrastructure projects can be rendered jobs rich, they should not be relied on to create substantial employment in a time of crisis.

This also depends on the nature of the nation. When I was working in South Africa on the Expanded Public Works Program, I supported large-scale, labour intensive road building projects that would use ‘old’ technology because it was the best way to maximise employment per km of tar laid.

Engineers who had studied this assured me that the quality of the tarmac was not determined by whether a capital-intensive or labour-intensive approach was deployed.

In other nations, where the need for job creation might be less, the projects can use best-practice technology, which will create less jobs.

There are many short-term projects that can be implemented quickly that can provide large numbers of jobs if needed in a sharp downturn.

Conclusion

The point is that Friedman’s observations about time lags was overstated when governments maintained internal planning capacity and took a forward-looking approach to nation-building.

As neoliberalism took its ugly grip on governments and destroyed a lot of that capacity, then it was valid to think about policy lags. Simply because the capacity to avoid them was decimated.

That doesn’t mean Friedman’s claims that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided.

It just means we have to ‘Reclaim the State’ and reinstate the capacity that is necessary to make fiscal policy interventions work in an effective manner.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Tis’ but a flesh wound!!

Bill wrote,”That doesn’t mean Friedman’s claims that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided.”

Did you mean,”That doesn’t mean Friedman’s claims that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided were correct.”?

OR, did you mean, “That doesn’t confirm Friedman’s claims that discretionary fiscal policy should be avoided.”?

Or, …?

The dystopian eurozone is working as an imposed shackle by a colonial power towards the colonies.

More or less what happened in Africa until the 1960’s.

Similar crisis happened all over the world, including the UK, the US, Japan or Australia.

In those countries, there are no doubts about the government ability to repay their debts.

And that’s because those governments, in fact, don’t need any debt, as MMT made it clear.

Debt is a self imposed burden, made to give the rich a safe haven to their money (and some they keep complaining about, because it’s profits aren’t as big as they wanted).

In the eurozone, countries like Portugal are one more time with the “damacles sword” shove their necks.

It will need a simple stupid comment from a Macron or a Merkel to make the sword fall.

It happened in october 2010, in a meeting of Merkel and Sarkozy in Deauville, that gave birth to the so-called eurozone-crisis.

It happened again last year when miss Laggarde said the “magic word” that sparked an imeddiate rise on the spreads of the Italian debt.

Above all, it’s more of economic sabotage, whether it’s on purpose or simple stupidity.

Yeah that one is a classic. Can’t decide if it is an example of typical British ‘understatement’ or if that level of interpersonal violence is more indicative of a failed state. Luckily the black knight only received minor flesh wounds and remained able to express his opinions throughout.

The rest of the essay was also great. Shows why we should have a Job Guarantee.

The Holy Grail not LOB

I used to work (in the UK) for a local authority on the NE Coast. It had numerous capital projects worked up, but which will probably never get the green light due to lack of funding. Of course the fact that the authority cut back its in-house project management and engineer capacity to the bone, will make it more difficult to get projects up and running. A number of projects could be designed as relatively labour intensive, per the South African choice. None would require the delay, environmental destruction (in fact the opposite), upfront spending of millions on compensating homeowners, and years long commitment as in a central government megascheme such as HS2.

@Rod White, yes MP and the Holy Grail. But I can’t decide which is more representative of the EU, the stubborn Black Knight impervious to needless harm, or Arthur as Ursula von der Leyen leading the pack for the Holy Grail of European Union and hacking off various limbs as she goes.

Another great blogpost which I shall use to make a submission to the UK LP National Policy Forum. 2 good quotes RT’d, including the one about hollowing out “capacity to plan and implement complex public policy interventions”.

In UK the public sector has lost expertise on almost everything important. Years ago there used to be a section of the Civil Service employing software system designers and coders. There have always been problems with software systems even when they were developed inhouse, but you learn on the job, don’t you? Now we’re totally reliant on a few multinationals who continue to make costly mistakes and are handsomely rewarded for doing so.

Hate to quote Marx time and again but even in 1865, referring to a debate opponent, “he would have found that this dogma of a fixed currency is a monstrous error, incompatible with our everyday movement.” Indeed, he showed that amount of currency required to circulate values vary daily.

With MMT now, we know that private banks create money ex nihilo.

Socialist Milton Friedman doesn’t know that. I have to agree with the lags that he recognized though.

Even back when Bernie was talking about infrastructure investments, I would occasional get the feeling that it was seen as a panacea.

Clearly, this blog shows that large projects are much longer term and cannot deal with short-term issues.

I think what the professor said about the capacity to plan and implement public policy is important. In that, I am afraid, such capacity has been hollowed out for years, like everything else.

I don’t think its possible for our exploiting class to change course on their own either.

I want to bring this discussion back to the nation with the highest per capita contribution to global Carbon emissions–Australia. It’s hard to know whether we are in the midst of a “lag” or looking at the prospect of one when it comes to dealing with catastrophic climate change and emissions reduction. But we certainly need to “reclaim the state” and MMT demonstrates the possibilities for Government funded action. The capacity for research and innovation in the area of renewable energy has not been destroyed . We have the resources available for a good start. Putting the global warming crisis and Just job creation up front and centre in Australia is already well researched and making small steps in the area of Concentrated Solar Thermal Power(CST) generation. This could be linked to creation of a national electrified High Speed Rail system.

Port Augusta would already have a functioning CST plant supplying South Australia with clean energy and jobs . Raindrop farms , again in South Australia uses CST to support a hydroponic tomato production enterprise which is world class. CST is being used in Newcastle and on a small scale in several other locations. Australia is exporting CSIRO developed Heliostats(CST mirror systems) to China for its rapidly developing CST programme. Combination of CST with rail electrification would not only eliminate fossil fuels but produce large numbers of jobs for a Just Transition in employment for green jobs and sustainable regions plus a wide range of sustainable industries which are already showing potential.

In 2010, Anthony Albanese ( then in government) released the Phase Two Report on High Speed Rail–he just seems to have memory lapse and has been duped into thinking that the only solutions are marketable solutions for energy such as batteries to store energy when the sun goes out–CST stores the Sun’s heat energy. It was the market that killed the Port Augusta CST Power station (and failure of Federal funding). Debate on emissions reduction and Global warming concentrates on marketable solutions such as batteries and electro voltaics (solar panels) without acknowledging their limitations, such as storage, life span, use of scarce resources etc. CST overcomes most of these problems and offers more positives. Instead of buying submarines and being belligerent to our neighbours we could collaborate (such as we are already doing with China and CST).

What is lacking is political action. No Australian political party seems to understand MMT but they also lack the commitment to action on anything . In 1917, we built the Trans Continental Railway to link the Eastern and Western States shortly after Federation. We built Snowy Hydro. Why not now? This is a political problem not a technological or theoretical matter.

“It just means we have to ‘Reclaim the State’ and reinstate the capacity that is necessary to make fiscal policy interventions work in an effective manner.”

And therein lies the solution!!; now to sound like someone I “pushed back against” on edX,

read Mitchell and Fazi . LOL(seriously)

Isn’t the reason governments issue debt is to give banks the ability to swap reserves (which are lumped on them when governments fiscal spend) for interest bearing treasuries?

@Dean,

Ye. Open market operations. But really MMT tells us there is really no reason for government to issue debt.

Free lunch for private sector essentially. I think after 2008, even reserves gives 25 basis point interest rate (support rate).

Government issues fixed rate term debt because there is a belief that is better for monetary policy than having floating rate perpetual debt. It’s a debate that has been going on for centuries.

What’s fascinating is that in the middle of the Victorian era Fixed Rate term debt by government was known as the “Unfunded Debt”.

916k jobs created in the US last month!!! U3 down to 6%…participation climbed higher

“The point is that Friedman’s observations about time lags was overstated when governments maintained internal planning capacity and took a forward-looking approach to nation-building.”

The UK now operates the “Boris Fawlty” school of governing. You somehow know a “U” turn is just a matter of time!

Is there any evidence that economic growth facilitated by fiscal spending can help solve economic problems? Won’t such growth simply result in more environmental damage?

John, maybe you would be interested in say, the WPA program. You could decide for yourself if it helped solve any of the economic problems of the people it employed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Works_Progress_Administration

@John additional government spending directed towards transitioning to renewable energy, towards energy conservation, recycling and away from wasteful materialism and towards management and restoration of the natural world will reduce our collective environmental destruction. Other areas of government spending like healthcare, agedcare, childcare, education, social welfare/pensions, the arts, public transport, rail infrastructure and so on do not have large environmental impacts but can benefit from more funding and growing productivity and GDP.

I maintain economic growth that generates full employment can be compatible with environmental sustainability and gradually reducing global populations if our governments are appropriately managed.

Human creativity, enterprise and innovation should be harnessed to drive technological and social progress and improving productivity while at the same time addressing the many problems and challenges we face.

Bill Mitchell: the Black Knight is from “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” not “The Life of Brian.”