I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Knowlegable economic commentary still exists

I saw the latest Government Finance Statistics released by the ABS today just after I read the Financial Times where there was an article by former Cambridge Professor of Modern History, Peter Clarke entitled This is no time to throw away the crutches. There was a symbiosis in time. Then I read all the geeing up that is going on about rising manufacturing output in China and Japan and the News Limited themes that we have to get interest rates up sooner rather than later or the inflation genie will escape and I remembered the real world.

In recent weeks, billy blog commentators here have been suggesting there is a wedge between what modern monetary theory tells us is possible and desirable and what politically is possible given the conditioning of the electorate in neo-liberal thinking. I agree that there is a hill to climb but that is what education is about and that is the career I entered. So it would be a denial of my role as an educator to just concede that opinions cannot be altered through better information, better logic and persistence.

But this is not a new thing. To give you a feel for what Clarke is arguing here is a quote taking from towards the end of his article:

“It is, it seems,” commented Keynes, “politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case – except in war conditions.”

This snippet of Keynes actually was published as J.M. Keynes, “The United States and the Keynes Plan” in New Republic, July 29, 1940. The context of this quotation was that Keynes was trying to reconcile the two-year recession in 1937-38 in the United States that some say demonstrated the failure of the New Deal. It is a common Austrian economics argument that fiscal intervention in the 1930s did nothing as evidenced by the double-dip in 1937-38.

Around 8 months into the 1937 downturn, the US government ramped up their large-scale federal spending which immediately say economic activity improve. Just as now! By mid-1938 the recovery was back on track and gathered pace (apart from a minor blip in 1939) through to 1940 when the military build-up in the US was well underway.

It was plain for all to see – the relationship between the successive spending pulses between 1933 and 1940 and the spurts in renewed economic activity was undeniable.

Only those who had an ideological obsession against government intervention (for example, the Austrian economists, and the extreme Treasury-line economists in the UK) thought otherwise. But this lot were content to spend their days behind closed doors Counting how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Their insights have never been very helpful and in the main are just plain wrong.

Critics of this undeniable relationship argued that the deficits under the New Deal had discouraged private investment which was “self-evident” (not!) given that private investment languished throughout the 1930s. So the New Deal was bad according to the conservatives. The mantra then was not that distinct to what we read and hear and see in the media now. The mainstream has always been against intervention in the market.

Anyway, Keynes wanted to combat that notion and in this article (The United States and the Keynes Plan) he argued that that the New Deal didn’t go far enough in scale to push the economy into full recovery. In other words, it was palliative and in that sense effective but never consistently large enough to restore full employment.

Keynes made the point that by the end of the 1930s there still hadn’t been a reasonable test of his theory – that sufficient net public spending was required to restore and maintain full employment.

In one sense, this is interesting because in the 1980s (in particular) the Monetarists argued that Thatcher’s experiments in public sector cutbacks, deregulation, privatisation and union-destruction in the UK were associated with appalling economic outcomes because the “Monetarist vision” hadn’t been taken far enough. There were still regulations that had to be abandoned and the unions hadn’t been fully wiped out. So in that sense the two claims have some mutual resonance. But that is about as far as I would go with that comparison … more Monetarism would have scorched the Earth!

Anyway, as the US decided to build its military capacity in 1940 (they didn’t enter the War until December 7, 1941), Keynes saw this as having the potential to be the (quoted in the July 29, 1940 edition of the New Liberal, page 159):

… grand experiment … [which would show for once and for all] … what level of total output accompanied by what level of consumption is needed to bring a free, modern community having the intense development of the United States within sight of the optimum employment of its resources …

The conclusion is that at all recent times investment expenditure has been on a scale which was hopelessly inadequate to the problem … It appears to be politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organize expenditure on a scale necessary to make the grand experiment which would prove my case except in war conditions.

So you can see that Clarke snippet, unlike our earlier quoter of Keynes this week Tony Makin, remained faithful to the original intent and didn’t choose to misrepresent the meaning of the section.

Of-course, the rest is history. The US military spending in 1940 and 1941 were easily enough to push that economy back to full employment after languishing for years with very high levels of unemployment. This NPS site is an interesting source of information for non-Americans.

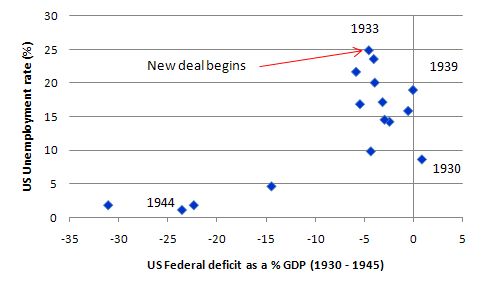

To see this in graphic terms here is a graph showing the US Federal budget deficit (-) between 1930 and 1945 plotted against the US national unemployment rate. The New Deal certainly reduced the unemployment rate but it wasn’t until the deficits really grew as a proportion of GDP that full employment returned. That did not occur until the defence spending was ramped up in 1940.

You can get the data in the graph from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Bureau of Labor Statistics – Historical Statistics US (1976) series D-86.

Anyway, the same pattern occurred all over the depression-ravaged world. It was beyond doubt that the war expenditure pursued by national governments in defence of their borders brought their economies quickly back to full employment. The experience did not render them insolvent and the main issue (or threat) was how to avoid inflation from occuring.

That little digression was an introduction to yesterday’s FT article by Peter Clarke, noted at the outset.

Clarke begins by noting that there is now positive news emerging all around the world such from China and Japan today and this will help engender confidence that recovery is possible and near. He then cautions us:

But it is dangerous, as well as tempting, to forget how bad things looked only a short time ago. This premature amnesia is not only psychological, burying painful experiences; it also has an ideological dimension, as seen in the US debate over the efficacy of the stimulus package and the bail-out of Wall Street. We are being told simultaneously that these measures have not worked – and that they were not necessary anyway. We are supposed to forget the frightening precipice over which we peered only a few months ago; and we are also asked to believe that what has saved the situation is the spontaneous resilience of the free market. Thus the bogey is “big government”.

Like many alarmist narratives, this story feeds on real fears. It is not unreasonable to worry about the size of current budget deficits. The fact that these deficits are partly due to bailing out banks that took unwarranted risks will not strike sympathy among taxpayers. The truth is that the alternative scenario was even worse – a systemic collapse of credit. But this is the bit that is too easily forgotten, innocently or otherwise.

Clarke then notes that the stimulus packages which have helped save the world economies from disaster are implicated by critics in generating “a deadweight burden” of debt “if not on us then on our grandchildren.”

He nicely states that:

What lends credence to such criticisms is not only our memory loss about recent events but our failure to benefit from a longer historical perspective.

Segue into the Great Depression again. Clarke rehearses the familiar argument that the New Deal might have been characterised as a Keynesian policy approach but in fact was not. He notes that Roosevelt hated the use of budget deficits and appointed a conservative Treasury secretary. Clarke says:

If modest deficits appeared in the federal budgets in Roosevelt’s first term, it was mainly a cause for political embarrassment.

But the reality was that the spending measures under the New Deal were expansionary even if it had to drag the ideologues along with it and three years later there was some steady recovery.

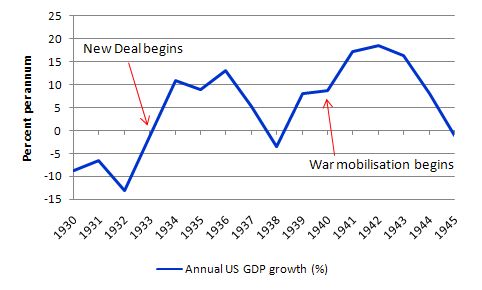

You can see this in the following graph which shows annual GDP growth in the US between 1930 and 1945.

However, the inherent conservatism of the Treasury secretary emerged in 1936. Clarke captures it like this:

… a modest economic recovery by 1936. Whereupon, Morgenthau sensed his opportunity “to throw away the crutches and see if American private enterprise could stand on its own feet”, with plans to balance the budget within two years. FDR went along, hoping to wrong-foot his relentless Republican critics. The results were impressive but perverse. Hesitant economic recovery was halted in 1937-1938 and the Democrats’ natural constituency was hurt by job losses in “the Roosevelt recession”, as political opponents gleefully dubbed it.

Once again you can see this set-back in the graph above. This pattern has been played out over and over again. Japan started to enjoy growth in the latter part of the 1990s after massive deficits underwrote aggregate demand. But the conservative lobby forced cutbacks and the economy went backwards again.

What has to be understood is that deficits are not temporary events that have to be eliminated as soon as the production processes show the most tepid signs of moving again.

It is really important to keep saying this: as long as the non-government sector desires to save the government sector has to be in deficit of an equal (offsetting) magnitude – $-for-$. If the government doesn’t follow this national accounting rule then the economy will never get close to full employment.

The growth period in Australia since the 1991 recession was largely achieved (especially after 1996) with a massive fiscal brake being applied to the economy and the household sector building unsustainable levels of debt.

Clarke puts it this way:

It remains true, however, that the New Deal did not cure unemployment, just as its critics maintain. But what the critics usually fail to add is that this was because the fiscal stimulus was too small. Only with the advent of the second world war was government spending set at a level that induced full economic recovery.

And we are back to the quotation from Clarke that I provided at the outset.

Now is not the time to cut back. The deficit has to keep building to support non-government saving and hence push production levels up again so that the labour market can provide enough jobs and working hours to fully employ the willing labour force. Any ambition less than that is a breach of common sense (and decency).

How do these characters con us into believing it is sensible to allow 10 per cent or 12 per cent or 16 per cent of our willing labour resources to be in idle – either through unemployment or through underemployment? The daily GDP losses of that idleness not to mention that massive social and personal costs do not bear thinking about.

Yet we believe that some numbers on a bit of paper – the size of the deficit or the amount of public debt – are more important. More the fools us.

Clarke finishes by noting that:

At any rate, military expenditure appears to enjoy a continuing exemption from kneejerk abhorrence of big government in the US. Indeed, the present scale of US public debt is largely a result of the deficits generated by the previous administration to pay for wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Had the inherited Bush deficit been smaller, the relatively small Obama deficit added by the stimulus package could have been financed more easily. But real-world conditions are seldom ideal or policy choices straightforward. Historical parallels are likewise seldom exact, though they are sometimes worth remembering.

The other point to note by way of closure is that Keynes was talking about loan-backed spending during a Gold Standard period with fixed exchange rates. Now, under a fiat monetary system, we no longer have the constraints on national governments that existed then. It is much easier for governments to create full employment using budget deficits.

They could do so without any increase in public debt (or tax rates). They would still face the same inflation risk at the top of cycle. Arthur Okun (one of my favourite economists) didn’t call the fully employed economy (which he revered so much as the exemplar of public purpose in policy) – the high pressure economy – for nothing.

The challenge for progressives continues. It is to impress on the wider public that there is no comparison between millions of people without jobs and lost incomes and some numbers coming out in the ABS statistics today telling us what the Federal government budget situation is.

We also have to understand the opportunities that a modern monetary system provides the sovereign government. In terms of inflation risk, the national government can always control that using appropriate fiscal policy settings and ensuring that it doesn’t compete at market prices for resources once the high pressure economy is achieved.

The latter insight refers to the need for a Job Guarantee where the government would buy any idle labour at a fixed price (minimum wage). in doing so it stabilises the general price level because the buffer stocks of jobs in the Job Guarantee represent a nominal inflation anchor. But this blog is not about that.

Anyway, it is nice to read an article occasionally in the popular press that isn’t a debt/deficit beat up written by some ignorant ideologue. An article that actually reflects a deep knowledge of economic history and a wisdom to understand what it means for us all now.

Keynes advocated large scale spending because at the time taxes on most people (in the US) were very low. There was no payroll tax and the income tax was very low. While I agree with you that spending should be targeted to directly create jobs, this does very little for the people with jobs but do not have sufficient income to save and consume. I think in today’s era of high taxes on the middle class (case in point: my wife is self employed and pays both the employee and employer payroll taxes, plus her income is added to mine so all of the remaining income is taxed at 25%), Keynes would agree that some of the “net spending” you advocate should come in the form of tax relief for the middle class.

Dear MarkG

Whether you want to compose a stimulus via direct spending or tax relief is a matter of circumstance and politics. The government needs to ask whether they want the private sector to have more purchasing power or not. If yes, then tax relief is useful.

But there should be no-one left without a job or sufficient hours of work just to give those who already have work some tax relief. The government must ensure everyone has work as a basic principle in my view.

But from a technical perspective (not my values), tax relief $-for-$ is not as stimulatory as direct spending because some of it is saved.

best wishes

bill

MarkG,

I have read John Maynard Keynes and John Neville Keynes extensively. Who is this third member of the Keynes family you are referring to ?

cheers, Alan

Dear Bill,

You do realise that hardcore Austrians refer to monetarists as Keynesians ?

Cheers, Alan

Dear Alan

I know. Sad as it is. I am getting a lot of requests to give my view of the Austrian School but I find the conjunction … Austrian and School to be confronting because schools are where you learn useful things.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

Maybe you could refer people to a Book called “Economics in One Lesson” by Henry Hazlitt.

If they still want to know your views about the Austrians after reading Hazlitt’s book then I’d simply render them beyond saving and act accordingly.

cheers, Alan

Dear Bill

I’m wondering, will this brief period where the major western private sectors are showing a desire to net save or atleast not borrow as vigorously as before, allow for the conservatives to implement their cost cuttings and tax increases once they feel confident enough to lose the crutches [or atleast to lose one crutch] ?

In another words the next few years of large deficits and zero interest rates is respite for households in terms of debt accumilation, before they reassume their role of debt accumilators to allow the govts. to reduce the size of deficit. I can’t imagine the UK, US and Australian private sector ever showing the same kind of prolonged appetite for saving as the Asian private sectors like Japan. This period of saving and paying down of debt will actually result in dramatic wealth accumilation i believe which will put households in a position to fund more, much larger speculative bubbles with cash and debt. This i believe is the end result of this irrational fear of deflation in my view. It was the case after 2001 when deflation was again the big fear, why should it be any different this time. As the author states, memories are short.

I’m also curious when you talk about private sector spending automatically reducing the size of the deficit. Before, when i’ve asked you about countries like the UK running smaller deficits for several years during the noughties, you said that the deficits weren’t large enough or prolonged enough……but wasn’t it more the case that the size of the deficits were reflecting consumer recovery from the 2001 mini-recession and the other minor economic palpatation that occured around 2004/2005 which threatened to kickoff the housing market slide but didn’t due to central bank response.

I had almost asked you, Bill, to give your thoughts on another popular blog that seems to follow the Austrian thought pattern but there is all ready a commenter on the relevant thread doing that job. And quite well I might add.

Tricky,

No.

Cheers

Dear Tricky

In terms of your last point (about the UK etc) the two statements you make are not inconsistent. First, yes the automatic stabilisers were reducing the size of the budget deficit as consumer spending recovered. Second, the discretionary component was not large enough because there were still people who wanted to work jobless or underemployed and the state of public infrastructure still in a degraded state after the devastation that the Monetarists left behind.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

As I said in my comment, I support a JG or ELR program. But how will giving a minimum wage job to the unemployed translate into productivity gains being distributed to labor?

I believe that the babyboomers retirement will act as a significant automatic stabilyzer as the govt “returns” the fictional “trust fund” to the public. This assumes the govt does nothing else to screw it up. The smaller workforce and greater aggregate demand should give labor more bargaining power and hopefully better income distribution. But this is still 10 years down the road. In the mean time, govt needs to provide tax relief if the middle class is to see any improvement in living standards (other than improvements in the public sector).

“In the mean time, govt needs to provide tax relief if the middle class is to see any improvement in living standards (other than improvements in the public sector).”

I was laughing so hard I forgot what I was going to type.