I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

It is good they are not in Treasury any more!

In today’s Australian newspaper ex Federal Treasury official Tony Makin writes that We keep repeating Keynes’s mistakes. Do we now? The story is a litany of half-truths and basic conceptual errors. He is now a professor of economics. Bad luck for his students. The article, one of a regular contribution he makes to the increasingly squawking right-wing News Limited daily, is a classic example of how to deceive the public with spurious economic reasoning – that the author knows most of the public will just accept without question.

Makin also publishes through the right-wing think tank Institute of Public Affairs (not that the thinking at the IPA is at a very high level). A few weeks ago, that august (not!) organisation was represented on the SBS Program Insight program by one Ms Novak. You might recall that the program was based on the work I did with Scott Baum work on the Employment Vulnerability Index.

She is also an ex Federal Treasury official. You can read the transcript HERE and watch the full episode HERE.

To give you an idea of how hysterical the IPA is, I offer the following snippet. Apart from rehearsing the standard neo-liberal deficits/debt hysteria, Ms Novak said this in relation to job creation:

… But Government funding of itself will not yield sustainable, real jobs. It is the market economy that delivers jobs …

In reply I said (at 57.00 minutes into the program):

The idea that the private sector has ever provided enough jobs to satisfy the labour force is historically wrong.

If you watch the video of the program you will hear Ms Novak retort in the background “they did so”. This was very loud in the TV studio but is muffled on the live show because the microphone was centred on my comments at the time. But you can hear it just fine. So what is the evidence?

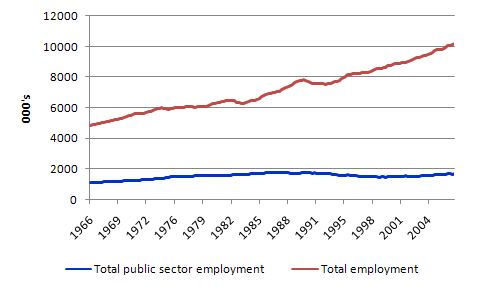

I plan to write more about the decline of public employment in another blog once I have a complete data set. But this graph will show you how absurd the comment Ms. Novak made was. It is from June 1966 (the earliest date available) to September 2007 (the latest available which is comparable). It shows total public sector employment (blue line) and total employment (red line) in Australia over that period. The data would extrapolate in more or less the same manner right back to the beginning of the white settlement.

First, my statement holds – the private sector has never provided enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available labour force (and after 1975 the gap became bigger because unemployment rose).

Second, you can see the demise of public employment that began in the early 1990s. This decline is all down to federal level employment as the government started to become obsessed with achieving budget surpluses and were cutting public spending back dramatically. This trend started under Labor – never forget that. It accelerated under the conservatives post 1996. I have simulations that show if the public share of employment had have kept pace from the early 1970s on, we would never have had any significant unemployment.

I would never believe a word the IPA publishes or its associates say. They are a neo-liberal propaganda machine well funded by the top-end-of-town to pursue the interests of that class.

Anyway, back to the main theme of this blog. The digression was to show how discredited the IPA is.

Makin claims that whether we support the use of fiscal stimulus packages or not:

… depends on whether we accept or reject the more extreme ideas of the celebrated English economist, John Maynard Keynes …

He then chooses a few sentences out of Keynes’ 1936 General Theory to show how dangerous Keynes’ ideas were for liberty and public policy.

Makin says:

… in the concluding chapter of his best-known work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, asserted, completely wrongly as it turned out, that in the post-Depression era “comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment”.

And that: “The central controls necessary to ensure full employment will, of course, involve a large extension of the traditional roles of government.” In the same chapter Keynes also wrote of the “cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity value of capital”.

Keynes’s central planning approach to fiscal policy was credited by his disciples in the 1940s and 50s with saving Western capitalism from itself

So central planning – socialism – communism – oppression – deprivation of liberty … ideas that Makin is attempting to invoke and goad the reader into conflating. The intention is to reinforce the neo-liberal prejudices against fiscal activism.

But if you read Chapter 24 (the last in the book) you will see how selective the Makin quotations are. First, in Section III you will read the following paragraph (I have bolded the part Makin selectively quotes):

In some other respects the foregoing theory is moderately conservative in its implications. For whilst it indicates the vital importance of establishing certain central controls in matters which are now left in the main to individual initiative, there are wide fields of activity which are unaffected. The State will have to exercise a guiding influence on the propensity to consume partly through its scheme of taxation, partly by fixing the rate of interest, and partly, perhaps, in other ways. Furthermore, it seems unlikely that the influence of banking policy on the rate of interest will be sufficient by itself to determine an optimum rate of investment. I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment; though this need not exclude all manner of compromises and of devices by which public authority will co-operate with private initiative. But beyond this no obvious case is made out for a system of State Socialism which would embrace most of the economic life of the community. It is not the ownership of the instruments of production which it is important for the State to assume. If the State is able to determine the aggregate amount of resources devoted to augmenting the instruments and the basic rate of reward to those who own them, it will have accomplished all that is necessary. Moreover, the necessary measures of socialisation can be introduced gradually and without a break in the general traditions of society.

Note, he even left out the qualifier somewhat while he mis-represents the intent of the sentence in that paragraph. Very poor scholarship! Bad luck for his students.

The second part of Makin’s quote is taken from this paragraph in Chapter 24. Read it fully and you will that get a different view to the one Makin is attempting to present:

The central controls necessary to ensure full employment will, of course, involve a large extension of the traditional functions of government. Furthermore, the modern classical theory has itself called attention to various conditions in which the free play of economic forces may need to be curbed or guided. But there will still remain a wide field for the exercise of private initiative and responsibility. Within this field the traditional advantages of individualism will still hold good.

Again, poor scholarship. First, the references to a “large extension” refers to the fact that governments of the day had virtually no macroeconomic functioning. So a large extension from nothing! Second, Keynes was an antagonist towards socialism and anti-Marx. He was a devout defender of the private market economy. Much too much for my liking.

Finally, the “oppressive capitalist” reference. Here is the full paragraph where Keynes is saying that if the private sector investors (capitalists – using the terminology of the day) do not wish to invest then it is the responsibility of the state to fill the gap and that they have the capacity to do so. Nothing at all to do with wiping out the capitalist system.

Now, though this state of affairs would be quite compatible with some measure of individualism, yet it would mean the euthanasia of the rentier, and, consequently, the euthanasia of the cumulative oppressive power of the capitalist to exploit the scarcity-value of capital. Interest today rewards no genuine sacrifice, any more than does the rent of land. The owner of capital can obtain interest because capital is scarce, just as the owner of land can obtain rent because land is scarce. But whilst there may be intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of land, there are no intrinsic reasons for the scarcity of capital. An intrinsic reason for such scarcity, in the sense of a genuine sacrifice which could only be called forth by the offer of a reward in the shape of interest, would not exist, in the long run, except in the event of the individual propensity to consume proving to be of such a character that net saving in conditions of full employment comes to an end before capital has become sufficiently abundant. But even so, it will still be possible for communal saving through the agency of the State to be maintained at a level which will allow the growth of capital up to the point where it ceases to be scarce.

Again, poor scholarship. Bad luck for his students.

Makin then mounts the usual neo-liberal trash that the escape from the Great Depression was nothing to do with fiscal policy. The argument is that there was in fact “a prolonged contraction of liquidity, policy-induced investment uncertainty, and large-scale retreat to international trade protectionism.” I might write separately about this in another blog. It is part of a book I am writing which aims to expose these myths once and for all.

The Great Depression ended with the onset of World War II when governments used massive fiscal injections to prosecute the military effort. This had the fortuitous outcome of restoring full employment (minus the soldiers that died!). The credible economic historians all agree with that version of events. The rabid right have been trying to reinvent history ever since.

Makin attempts to further discredit the use of fiscal policy in this way:

The enduring appeal of Keynes’s theory was that it offered a cogent explanation of the main components of the national accounts and the phenomenon of the business cycle, while simultaneously asserting that governments could easily and at little cost correct macroeconomic misbehaviour at will and as it saw fit.

But this has always put Keynesianism at odds with the centuries-old tradition of economics that emphasised how prices automatically equilibrated markets and which suggested minimum government involvement in commercial exchange as the best means of allocating an economy’s resources.

After World War II ended, governments all round the world sought to maintain the full employment they had achieved (for the first time in monetary history) without recourse to war-time expenditures. In other words, they knew that had to maintain high levels of aggregate demand in the peace. So from 1945 until 1975, they manipulated fiscal and monetary policy to maintain levels of overall spending sufficient to generate employment growth in line with labour force growth. This was consistent with the view that mass unemployment reflected deficient aggregate demand which could be resolved through positive net government spending (budget deficits). Governments were typically in deficit during this time.

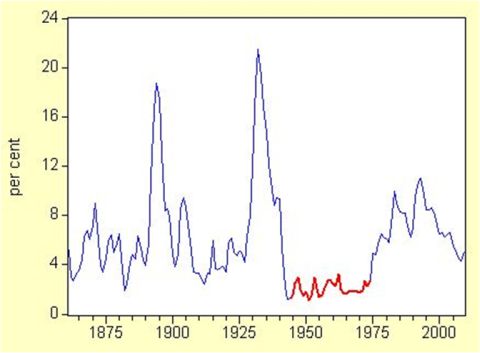

As a consequence, in the period between 1945 through to the mid 1970s, most advanced Western nations maintained very low levels of unemployment, typically below 2 per cent. Here is a graph you will have seen before that charts the history of the unemployment rate since 1861. The red segment is the “full employment period” and it stands out in stark contrast to the periods before it and since.

Makin is just plain wrong that free market price adjustments delivered high levels of employment. The periods outside the Keynesian era were marked by considerably greater volatility in economic activity and high levels of unemployment. The average for Australia outside the red-line period in the graph was around 6 per cent.

You cannot systematically waste the most important resource available to the economy – human potential – and claim you are adopting the “best means of allocating” resources. Total nonsense and a distortion of history that is there for all to see.

Makin then argues that the world today is a different place to that considered by Keynes – for example, there is now relatively free flow of international capital and Australia is a very open economy. Accordingly, developments in economics since, which began soon after the General Theory came out – Makin cites the IS-LM analysis of Hicks – have allegedly rendered Keynes’ insights erroneous to the problems of the present day.

As a result the profession adopted a new way of thinking about macroeconomics which is captured by the mainstream textbooks which are still forced onto students today. For example, Makin himself uses the standard macroeconomics book by Mankiw which I have written a bit about before – see these blogs.

Mankiw’s macroeconomics is a gold-standard type exposition of an economy that bears little relation to the fiat monetary system we live in. The book doesn’t offer any credible insights into the economic opportunities that are available to a sovereign government in a fiat monetary system. The impacts of fiscal policy are mis-represented in the extreme. The monetary theory advanced in the textbook is inapplicable to our economic system – money multiplier, loans constrained by reserves, quantity theory of money, loanable funds doctrine to explain interest rates and more. It is a disgrace.

But given that, it is no wonder the Makin tells his readers this morning that:

… this framework actually shows that fiscal stimulus can quickly drive up interest rates, crowding out private investment to the longer term cost of the economy.

Those of you who understand modern monetary theory will immediately realise this is completely wrong. I guess Makin has forgotten that Japan, the second-largest economy (perhaps even still) exists.

Deficits drive interest rates down. They provide a positive platform for private investors who were stalling investment plans because aggregate spending was falling. Deficits finance private saving and restore stability to the macroeconomic system.

Makin also attacks Keynes’ assumption of inflexible wages and says that they are less relevant now. He says:

Another critical assumption of Keynes’s 1936 work was that wages were inflexible downwards. While rigid wages were necessary to make Keynesian fiscal policy work in theory, this assumption is now less relevant in practice.

The prime purpose of fiscal stimulus has always been to preserve jobs. Yet, ironically, greater labour market flexibility than in previous recessions is doing that by itself.

First, to be accurate, Keynes was talking about nominal or money wages in this context not real wages. He was totally cognisant of the fact that real wages would fall in an expansionary phase but he eschewed the causal connection that neo-liberals still want to make (including Makin) that the lower real wages stimulated the employment increase.

Keynes’ knew full well that the coincidence between falling real wages and rising employment was a case of “observational equivalence” which arises from correlation rather than causation. He said that while the neo-classical (old neo-liberals) economists saw this correlation as causation, in fact, it arose from the real wages and employment being jointly correlated with rising economic activity driven by spending. So it was effective demand (demand backed by willingness to pay) that drove employment increases and (given Keynes’s false assumptions about cost structures) rising prices.

Second, we still are not in a system where we cut money wages. Real wages clearly fluctuate for for various reasons but rarely because money wages are cut.

Third, the employment that fiscal policy supported in the Post World War II growth period (up to around 1975) were full-time, well-paid, stable and high productivity jobs. The flexibility that Makin seems to be lauding now has undermined productivity growth by increasingly allowing employers to “race to the bottom” and provide casualised, low-paid employment with deficient hours.

It is simply not true that the flexibility which was promoted by pernicious government-legislated attacks on trade unions; attacks on wages and conditions etc has preserved working hours. In the current downturn, underemployment has sky-rocketed. Since the 1991 recession, as government legislation has turned increasingly nasty towards workers rights, underemployment has risen. Further, employment measured in persons is now falling all around the world including Australia.

The problem now is that the fiscal injection has not been strong enough or directed at direct job creation. The flexibility Makin admires has helped to reduce Australia as a high-productivity, high-wage economy capable of producing jobs (and hours) that satisfy the preferences of the workforce. The increasing insecurity of employment and destruction of entitlements has also reduced the incentive of individuals to invest in human capital and that alone will reduce our future growth potential.

Makin again tries to reinvent history:

Historically, Keynes’s intellectual influence over policy-making reached its zenith overseas and here in the 70s, which was easily the single worst decade for economic performance in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development region since the Depression.

That decade was characterised by Keynes’s legacy of high budget deficits and high public debt, which in turn contributed to persistently high inflation, stagnant stock markets and high unemployment.

No mention of the largest oil price hike in modern history via the OPEC cartel. The 1970s were an appalling decade because governments failed to react to the supply (cost) shock adequately. The malaise was worsened by the contractionary fiscal and monetary policies that defined their response to the cost crisis. The inflation was distributional – a failure of labour and capital to reach an appropriate accord on how the imported raw material cost rises would be shared between them.

Further, in terms of appalling rates of labour underutilisation, the 1990s were much worse than the 1970s and this was under a government policy regime firmly centred on the macroeconomics that Makin supports – a lack of fiscal intervention.

Anyway, all of this is largely irrelevant to the main issue.

What Makin fails to understand about Keynes is that he is largely of limited relevance now for different reasons. In Keynes’ time there were fixed exchange rates and a gold standard operating. His analysis was also largely confined to a closed economy.

The fact that we now have a fiat monetary system provides greater sanction to fiscal policy to do the work that Keynes foresaw for it – that is, to underpin private saving and ensure aggregate demand is sufficient to generate full employment.

I am glad Makin isn’t anywhere near Treasury these days although his ideas are still prevalent in that institution. The only downside of him having moved into academic life is borne by the students who have the misfortune to sit in his classes.

I read his article this morning. Though I am not intimately familiar with the General theory (I read it but did not properly understand it) I knew that his argument was simply neglecting to present the whole picture such as the impact of the 1970’s OPEC oil shock and the fact that the Keynesian era before that was a very prosperous time with very low unemployment and strong growth and nation building.

I suspected that his qouting of Keynes was selective but now that you have shown just how far he goes, I find it disgracefull that a professor who teaches up and coming economists would engage in so much public lying by omission.

Are there no penalties for a professional academic behaving in such a fashion?

Related issue: Something I DID get from reading the works of Keynes was that he was rather an elitist snob with a sense of superiority and class distinction!

Makin states the 1970s was characterised by high levels of public debt. The US public debt to gdp ratio reached a post war low of about 25% in the 1970s. Although govt was running deficits in the 1950s and 1960s, gdp growth caused the ratio to drop. Bill, is there any significance to the level of debt to gdp ratio? Here in the US, the ratio was under 40% from about 1968 – 1982 and again from 1999 – 2007. Both periods had a flat stock market (ups and downs but ended about where it started), higher unemployment, and unstable prices. I have asked this question to some mainsteam economist and they said the 50s and 60s were good because the ratio was falling. Of course they had no answer for the 80s and early 90s when the ratio was increasing (except for a drop in the ratio just before the 91-92 recession).

About your last point: I’ve always found it ironic that economists stopped believing in Functional Finance just as the last vestiges of the gold standard were removed by Nixon and it finally became feasible…

If I may follow your digression a little and work quickly under the assumption that the lady’s comment that the private sector has provided enough jobs for the labour force at any point in time, it can still be dismissed as having available employment in the wrong locations, most likely where there would be high labour mobility costs (too expensive to get there or move there to be worth your while) thus having low or full employment in one area and high unemployment in one or more other geographical areas.

Makin is a complete hack who wouldn’t know the economics of Keynes from Hicks. More people were influenced by Hicks’s erroneous review of Keynes’ 1936 book than by the original book itself.

Nice work Bill for exposing Makin for what he is.

Dear MarkG

I don’t place much significance in the public debt to GDP ratio as a standalone policy concern. It can rise for good reasons and for bad reasons as you note. If you have a voluntarily imposed rule (legislated in the US) that each dollar that the national government is in deficit a dollar’s worth of public debt has to be issued then the debt level will just reflect the accumulated deficits. The question then is why have the deficits risen. We know they will rise if GDP falls as the automatic stabilisers kick in (tax revenue falling and welfare payments rising). So in this case the public debt to GDP ratio will be rising and the economy will be in bad shape.

Alternatively, the deficit might rise if the government actively seeks to “finance” private saving and ensure the output and employment levels are high. This could push the public debt to GDP ratio (depending on output growth rates and the real interest rate) but you would see an economy at full employment and in good shape.

So there is nothing particularly useful about the ratio. It is far better to focus on the extent to which the government deficit is underpinning desired levels of non-government saving and maximising employment. If the public debt to GDP ratio to accomplish that was 30 per cent or 100 per cent – it would be of no real concern.

The reason that the mainstream keep talking about it is that underlying their concern is a false notion that the sovereign government can become insolvent. Further, they believe that rising debt ratios mean rising deficits which drive up interest rates and cause inflation. None of these concerns are well-based in concept.

best wishes

bill

These may well be stupid questions, as I’m a not an economist – happy for anyone to reply not just Bill.

So if saving removes real-cash from an economy, then surely compulsory superannuation must come in to play? 9% of income is effectively saved – or removed from the economy. Did this not also come in around the 1996 / end of Keating period?

On a personal level – Baby boomers (which are always the problem for everything 🙂 being a large proportion of the population, surely would control a large percentage of the national savings which they are hoarding for retirement. They own the houses which most Gen X and Y’s rent. Does this inequality and higher savings level effect the value of say a Gereration X or Y’s money in real-terms?

– shaun

Dear Bill,

Do you really think the mainstream / neo-liberals are stupid enough to think a sovereign government can become insolvent or that “rising debt ratios mean rising deficits which drive up interest rates and cause inflation?”

Personally I don’t buy it that they could be that stupid. Rather, I see it that their position is to widen the gap between rich and poor and if that means telling lies then they are more than willing to do so.

If indeed the mainstream / neo-liberals are indeed stupid enough to have simply gotten it all wrong rather to have been behaving strategically then why bother trying too bring them around to the truth if they are idiots ?

Cheers, Alan