The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Cutting wages in a deep recession is not a sensible policy

Victoria went the so-called ‘double doughnut’ again today with zero new infections and zero deaths – the fourth consecutive day. It now has the lowest number of people sick with the virus (known) since the start of the pandemic in Australia in February. Only 38 active cases remain in Victoria after its 12 week lockdown. There is no community transmission reported now in Victoria and the other day Australia recorded zero (community transmitted) cases overall. So things are less tense than they were. I still haven’t been able to travel to my office in Melbourne which I have been away from since the lockdowns started in June. But hope springs eternal that the NSW government will open the border and let us move freely between the States. At the same time, the NSW government is demonstrating its economic incompetence. The State Treasurer announced that in the midst of the worst crisis in 100 years, it is cutting the pay of its public servants when it brings down its fiscal statement. Clue: when in a deep recession with records levels of household debt dramatically constraining growth in household consumption expenditure, which in turn, is killing growth, then the sure fire way to make matters worse by cutting the very source of consumption expenditure – yes, you get it – workers’ wages.

This is on the back of a decision by the NSW Industrial Relations Commission – Application for Crown Employees (Public Sector – Salaries 2020) Award and Other Matters (No 2) [2020] NSWIRComm 1066 (October 1, 2020) – which made the:

Determination that salaries and salary-related allowances in the awards the subject of the applications should be increased by 0.3% with effect from the first full pay period on or after 1 July 2020.

The government’s wage norm is that all “public sector employees receive a 2.5% increase each year”, which means a very modest real wage increase per year.

Initially, the NSW Government tried to introduce a wage freeze in June but the legislation was blocked by the Opposition and cross-bench members, which meant that it went to the Industrial tribunal (the Commission) for adjudication.

The Commission claimed that if there was a wage freeze, workers would endure a 0.3 per cent real wage cut, which was rather contentious given that the inflation rate is much higher than 0.3 per cent.

But using that logic, they determined to maintain the real wage value by awarding the 0.3 per cent increase.

Looking ahead, the NSW government has now said that in its upcoming fiscal statement due out in a few weeks that they will reneg on the 2.5 per cent wage promise next year and cut it by 1 per cent.

They claim this will help to reduce unemployment.

Well, wages are an income. Income promotes spending. Spending drives employment.

History tells us that when nations are caught in deep recessions, and the authorities start cutting wages, that the recession gets even deeper.

We are once again walking the plank for a flawed ideology.

And the other relevant factor is that the 2.5 per cent wage norm that the state governments adopted as part of their obsession with recording fiscal surpluses and apparently appeasing the (irrelevant) ratings agencies, was already creating recessionary tendencies before the pandemic hit.

Even the central bank government acknowledged that.

Public sector wages growth has been very low for some years because state governments have invoked wage norms, allegedly to protect their credit ratings.

It is one of those nonsensical arguments that keep repeating.

It goes like this:

1. We have to run fiscal surpluses and cut our borrowing.

2. Why?

3. To avoid the credit rating agencies downgrading our debt rating.

4. Why would that matter?

5. Because then our borrowing costs will rise.

6. But if you are running surpluses and not borrowing then how does the rating matter?

7. Duh!

The point is that these wage norms have made it much harder for workers to gain real wage improvements and have contributed to the escalation in household debt as workers use credit instead of wages growth to maintain household consumption expenditure.

There is clearly a case to be made for wages growth in the Australian state public sectors to increase considerably.

That is, certainly the view of the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, who also considers the state has the fiscal capacity to allow for an acceleration in public sector wages.

On August 9, 2019, the Reserve Bank governor, Philip Lowe, in evidence before the – House of Representatives Economics Committee – made mention of the fact that he “would like to see stronger wage growth in the country” and drew attention to the way in which the public sector “wage caps are cementing low wage norms across the country”.

Dr Lowe told the Committee that:

… the wage caps in the public sector are cementing low wage norms across the country, because the norm is now two to 2½ per cent, and partly that’s coming from the decisions that are taken by the state governments.

He also told the Committee that:

In the medium term, I think wages in Australia should be increasing at three point something. The reason I say that is that we are trying to deliver an average rate of inflation of 2½ per cent. I’m hoping labour productivity growth is at least one per cent-and I’m hoping we can do better than that-but 2½ plus one equals 3½. I think that’s a reasonable medium-term aspiration; I think we can do better, but I think we should be able to do that. So I would like to see the system return to wage growth starting with three …

… what is really important is the wage norms in the country … And the public sector wage norm I think is to some degree influencing private sector outcomes as well-because, after all, a third of the workforce work directly or indirectly for the public sector … But I hope that, over time, that balance could shift in a way that would allow wage increases, right across the Australian community, of three point something.

In the evidence to the House Economics Committee, Dr Lowe (referred to above) said:

The public sector, directly and indirectly, employs roughly one-third of the labour force, and they’re saying wage increases across the public sector may be averaging two per cent. That has as indirect effect on the private sector, because there’s competition for workers and it reinforces the wage-norming economy at two-point something …

… if … wages in the public sector were rising at three per cent, then over time I think we’d see stronger aggregate demand growth in the economy. I don’t think it would have much of a negative effect on employment; in fact, arguably it could be positive.

He also said that:

Most people are accepting wage increases of two to 21⁄2 per cent. And the public sector wage norm I think is to some degree influencing private sector outcomes as well-because, after all, a third of the workforce work directly or indirectly for the public sector. So I think it is an issue but, on the other side of the ledger here, it is important that state governments manage their budgets prudently. I have spoken to a number of state treasurers. They say, ‘We’d like to do more here but we’ve got a tough budget situation.’ So there is a balancing act to be completed here. But I hope that, over time, that balance could shift in a way that would allow wage increases, right across the Australian community, of three point something.

When I have given evidence in recent wage cases as an expert witness, this last quotation is used against me, where the government’s counsel says that the RBA governor was making it clear that state governments may not have the fiscal capacity to deliver higher wages and the soundness of their fiscal position is paramount.

Well, the economics debate has progressed over the last 12 months in so many ways.

It is clear that the Governor now considers the states have much wider fiscal space than has been commonly considered the case.

On August 14, 2020, the RBA presented their – Annual Report for 2019 – to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics.

The same venue, a year later.

During the Question Time from the Committee, the RBA Governor, Dr Lowe was asked a question that bears on his interpretation of the available fiscal space at the State and Territory level.

He was asked by the Chair of the Committee:

Do you think the states should be doing more? When you’ve got the Commonwealth currently spending about $314 billion and the states only contributing about $44.8 billion so far in spending to assist, would an increase or a shift in responsibility to the states help aid the economic recovery?

He replied:

I think we need both the federal government and the state governments carrying their fair share … The measures to date from the state governments add up to close to two per cent of GDP. So, in aggregate, those measures are smaller; they’ve largely focused on supporting businesses through this difficult period and extra spending on health, and in some states there’s been extra spending on infrastructure and on housing and skills development.

Going forward, the challenge we face is to create jobs, and the state governments do control many of the levers here. They control many of the infrastructure programs. They do much of the health and education spending. They’re responsible for much of the maintenance of much of Australia’s infrastructure. So I would hope, over time, we would see more efforts to increase public investment in Australia to create jobs, and the state governments have a really critical role to play there.To date, I think many of the state governments have been concerned about having extra measures because they want to preserve the low levels of debt and their credit ratings. I understand why they do that, but I think preserving the credit ratings is not particularly important; what’s important is that we use the public balance sheet in a time of crisis to create jobs for people. From my perspective, creating jobs for people is much more important than preserving the credit ratings. I have no concerns at all about the state governments being able to borrow more money at low interest rates. The Reserve Bank is making sure that’s the case. The priority for us is to create jobs, and the state governments have an important role there, and I think, over time, they can do more. But the federal government may be able to do more as well. We may need all shoulders to the wheel.

In later questioning he provided further clarification:

I think that’s where the debate needs to be: how much government spending should there be? Resolve that answer, and I’m not worried at all about the financing. The Australian and state governments will be able to finance themselves at extraordinarily low interest rates for a long period of time. So the financing constraint is not the issue.

Further, the RBA has also changed tack by tweaking its ‘long-dated outright transactions’ program, which involved quarterly purchases of government debt (for open market operations).

Since March 2020, they are buying government debt in secondary markets “to achieve a target for the yield on 3-year Australian Government bonds of around 0.25 per cent, as well as to address market dislocations” (Source).

By the end of September, the RBA had purchased federal debt worth $52,250 billion, and state/territories debt worth $11,098 billion.

Despite RBA denials, it is now funding significant proportions of the government deficits – both federal and state.

Harking back to the last great crisis

This harks back to the 1930s, when the British – Treasury View – claimed that fiscal policy was ineffective in changing economic activity (employment, unemployment) because it crowded out private spending or investment.

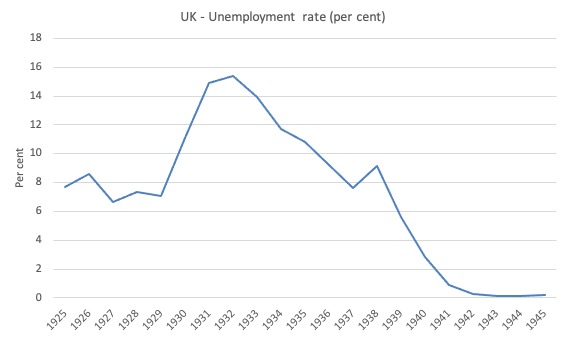

In 1929, British unemployment stood at 1.5 million (around 7.3 per cent of the labour force). By 1932, it had risen to 3.4 million (15.6 per cent).

The definitive data source is Feinstein, C.H. (1972) National Income, Expenditure and Output of the United Kingdom, 1855-1965, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Here is the UK unemployment rate trajectory for the period 1925 to 1945. It was really only the onset of the War and the military spending that went with the prosecution of that effort that ended the Depression and brought the unemployment rate down.

When Lloyd George went to the British people on March 1, 1929 as part of his pitch during the British election campaign, with his plan ‘We Can Conquer Unemployment’, which involved proposals for large-scale public works programs, he was rejected by the people.

The government then proceeded to introduce policies that guaranteed the impending downturn would become the Great Depression – and it was the Labour Party in case you have forgotten your history.

At the time they were barely distinguishable from the ruling Tories they defeated.

The document was prescient in that it laid out what would later become known as Keynesian economics, even before Keynes published his General Theory in 1936.

In fact, John Maynard Keynes helped write George’s manifesto.

But the proposal came up against the dominant British Treasury view of the day and they responded in May 1929 with a “Memoranda on Certain Proposals Relating to Unemployment”.

Winston Churchill was the Chancellor at the time.

It has all the main points that are continually (still) rehearsed today by conservatives (and even so-called progressives):

1. The state would become a “dictatorship”.

2. Workers would be coerced into wasteful endeavours.

3. The fiscal position had to be balanced.

4. There is only a finite supply of savings and government borrowing would crowd out private investment spending.

Even though unemployment was starting to sky-rocket and bankruptcies were rising sharply, they claimed the best strategy was to continue to run orthodox budgets (balanced) and let the markets sort the developing crisis out.

They concluded that the public works programs would not increase net employment because the increasing public employment would come at the expense of a decline in private employment as a result of the reduced private and foreign investment.

Churchill told the House of Commons in April 1929 that he supported:

… the orthodox Treasury doctrine which has steadfastly held that, whatever might be the political and social advantages, very little additional employment, and no permanent additional employment can, in fact, and as a general rule, be created by state borrowing and state expenditure …

I discuss all this in this blog post – We can conquer unemployment (September 24, 2010) – which was written more than 10 years ago! Shock!

The fact was that the Treasury view meant that the Chancellor would tighten discretionary spending during a recession to offset the automatic stabiliser components of the fiscal balance (loss of tax revenue etc) so as to maintain the balance target.

In other words, the conduct of fiscal policy in this period was strongly pro-cyclical and it is no wonder the recession became a Depression.

The – 1931 May Committee Report – advocated harsh, discretionary fiscal consolidation and the September 1931 fiscal statement delivered on that recommendation.

The Chair of that Committee was – George May – who was a London businessman and saw the government through that lens. The Committee as forced on the Labour party by cross-party political pressure.

The Committee was stacked – “four of the May Committee were leading capitalists, whereas only two represented the labour movement”. When the Report was finished, the two trade unionists refused to sign off on it, such was the recommendations.

The May Committee Report is very apposite today.

It recommended:

1. Wage cuts for public servants – teachers, police etc.

2. Cuts to unemployment benefits by 20 per cent, at a time that unemployment was rising sharply.

3. Massive cuts in overall public spending.

4. A general campaign to cut wages throughout the UK.

We learn that the May Report (commissioned by a Labour government no less) was a Trojan horse:

… to be used as a weapon to use against those Labour MPs calling for increased public expenditure. What it did in fact was to create abroad a belief in the insolvency of Britain and in the insecurity of the British currency …

Do I hear 1976 ringing in my ears. Dennis Healey. IMF bailout. Labour Party does it again …

The then chancellor – Philip Snowden – along with PM MacDonald were big supporters of the May Committee recommendations.

Clement Atlee – at that time, a Labour MP, said that Snowden had a “misplaced fidelity to laissez-faire economics.”

The internal rifts in the Labour government ultimately brough it down.

The point is that the wheel just keeps turning.

Conclusion

Cutting wages in a recession to ‘save’ money is one of the most misguided strategies a government can ever introduce.

The state governments have been given the imprimatur by the currency issuer (RBA) to spend heaps.

The RBA is buying up lots of state government debt.

There is no financial crisis – just a real one – unemployment and lost production.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

And the RBA have just announced that they intend to purchase an additional $20 billion or thereabouts in state and territory government bonds over the next six months, in addition to more large purchases of federal government debt.

Left wing Billy prospector

Any budgeting that hasn’t been offset with taxes needs to be borrowed. Makes the choices available as taxing, borrowing or defaulting. That story is completely wrong nothing more than a myth from the gold standard era. They ignore the fact that govt actually issue the money.

If there is always an option to finance the spending commitments with another instrument. Then saying the amount of debt the govt has restricted the Govt in some way is farcical. Saying they can’t do anything with tax due to the deficit or can’t borrow due to the debt then in effect they are saying they can’t spend. Due to their ignorance of monetary operations they have already lost the argument. With Brexit we need to win that arguement.

They need to stop thinking about it as money “and” debt. There are many different instruments that can be used. Those different instruments have different properties.Some you can use at a vending machine, Some you can use to make a transaction in the financial markets. Some pay interest some don’t, but are decentralised and some are anonymous erc, etc All of these are different types of govt liabilities. All of which are guaranteed by the govt at nominal face value.

Which one of the instruments you choose to issue is like comparing how many 10p you want to issue compared with £20 notes. That’s what you concentrate on what type of instrument am I going to issue and what do I want to achieve after we leave the EU.

You can make the argument about what instrument pays interest and what doesn’t. If interest payments as a % of GDP become so large and private sector spending is such that there is less non-inflationary room available for other discretionary spending then that is what tax is for. Tax – to reduce private spending and/or the government can reduces its own spending. But before that happens the current account, tax revenue (from higher activity) and saving will be taking up a significant part of the adjustment. Make it clear That government net spending is limited by the available real resources in the economy left by non-government sector saving desires. That the budget constraint needs to be replaced by an inflation constraint.

Saying Reserves that pay interest are debt and reserves that don’t pay interest are money leads you to a bizarre situation that if you are paying zero interest on reserves at the central bank that’s money. If you pay .25% interest on reserves that’s debt. Wether debt pays interest or it doesn’t is the wrong distinction to make. It’s a safe investment, a store of wealth, promised nominal value they are just different instruments that are being used. Or you decide not to issue it at all.

If interest rates were zero in both what’s the difference between a 3 month treasury bill which they will roll over forever and a coin ? Nothing they are just a different instrument. Some say you can’t spend a treasury Bill in a vending machine.Well try spending what’s in your ISA or in your fixed rate bond you can’t spend that in a vending machine either. You have to change it to another instrument first cash. You have to transfer it into your current account. It’s just a different type of debt instrument. We don’t call our savings a different type of money.

Consolidation between the central bank and treasury helps to explain the govt balance sheets clearly.The amount of treasury debt in circulation at any time. Is a decision made by the Treasury and CB together. Central bank independence is a sham.

The Treasury has discretion ex anti

The Central bank has discretion ex post

What the Treasury starts the central bank finishes.

If the central bank decides they want more 30 year bonds in circulation it has two options. To sell bonds it owns or asks the treasury to issue more.

If the Treasury only issued 30 year bonds and didn’t issue anything else.

The Central bank the day after decided to replace half of them with cash.

That’s exactly the same as if the Treasury issued only cash then the CB replaced half with 30 year bonds.

This shows it doesn’t really matter what instruments the Treasury issued to finance the spending. What really matters is the instruments the CB chooses to leave in circulation at the end of the process.If the CB wants more bonds less reserves, less bonds more reserves it will do whatever it takes.

The question how many bonds are in the economy is a question the CB is analysing at all times. The CB can set the curve to anything it wants. Instruct the Treasury not to issue 30 year bonds anymore and just to issue 10 year. Or issue 100 year bonds and create a new market if it chooses to do so. It sets the rate not bond vigilantes.

Example:

The treasury has been monitoring its spending for the month and needs £20 billion next month so it’s account doesn’t hit zero Treasury says to the CB we are going to issue more bonds next month.

The CB says we have a nice mix of reserves and bonds our balance sheet looks great. If we do nothing because we like our mix at the moment. That will take £20 billion reserves from the private sector. As the private sector will swap their reserves for the bonds you are going to issue. So an hour before your treasury auction we are going to buy up £20 billion of bonds that are already in circulation. This will create an extra £20 billion of reserve balances. We might not do it as a permanent transaction we probably do it as a REPO.

The CB does the REPO with a little sugar on top. Now the private sector has £20 billion extra in reserve balances. The treasury now carry out the auction and sell their bonds. The private sector have spent their £20 billion reserves balances have their bonds and the Treasury now has the £20 billion they needed.

The CB bought £20 billion worth of bonds The private sector reserve balance is back where it started with a little sweetener from the REPO. The treasury has £20 billion of new funds in its treasury account. The CB has monetised that debt through the back door.The CB has used the primary dealers to do it. The CB provided the funds with a little sweetener that the primary dealers then used to purchase the bonds from the treasury.Now the Treasury spends that £20 billion into the economy by crediting the reserve accounts.

The CB now says hey that’s upset our mix. We are going to reverse the REPO we did earlier.

The CB reverses the REPO. Takes £20 billion out of the private sector reserve balances and exchanges it back into bonds The CB has unmonetised what it did previously and now the private sector are holding more bonds than they did earlier. The CB is holding less bonds and reserves.

At the end of all that. You would say the Treasury has Borrowed £20 billion from the private sector and the private sector are holding a bunch of bonds. You wouldn’t even know the CB was involved and monetised anything.Yet, the truth is the CB and treasury work hand in glove. The CB at each step are in the middle making sure the mix is right between reserves( settlement balances) and bonds. Created the balance sheet it wants. It doesn’t matter if you fund the deficit by issuing coins or bonds.

The CB has the tools to distribute the different instruments and will continue to do so. Calling the CB independent misses the whole point. Fake progressives / conservatives miss all of it by not understanding any of it and the mainstream media are clueless so lie about it. Say it works like a household budget.

Actually the CB should just issue it’s own bonds. It’s cleaner more effective. Just as safe as treasury securities if not safer. Create its own account that has nothing to do with the budgeting process.

Well done to Victoria after its protracted lockdown. Here (England) the govt. thinks it can drive the virus out over 4 weeks, after giving it a boost for an extra few days until the Thursday shutdown, and while keeping schools and universities open.

The economic and political comparison with 1929 onwards is apposite. Churchill was replaced as Chancellor by the 1929 – 31 minority Labour government’s Viscount Snowden, but he had the same Treasury mental state. I guess one difference between then and now is that the Labour Party didn’t have to get rid of their left wing element because Lloyd George had seemingly sensibly stayed with the Liberals. The other day the BBC gave Alan Johnson (previous Labour home sec) airspace to comment on Corbyn’s banishment for not accepting that antisemitism from Labour’s much enlarged Corbyn led leadership was of tidal wave proportions. He couldn’t stop himself from saying that Labour’s democratic socialist tradition had to counter the revolutionary left. Talk about the terms democratic and socialist being captured and misused!

“There is no financial crisis – just a real one – unemployment and lost production.” If only we were so fortunate that the real crisis was confined to economics. “Employment” to do what? “Production” of what?” Aren’t these the real existential challenges now facing our species in light of the environmental crisis, which dwarfs the economic one? And yet we talk incessantly about the latter, as if the former could be bracketed and put on a distant “to-do” list. Solving the economic crisis will mean nothing, will at the most buy us a fleeting bit of time, until the environmental crisis is faced head on and somehow surmounted. MMT has much to say about how to begin to tackle this–targeting the JG, for example, in low-skilled but crucially important environmental work–yet this often seems to be a subtheme, an afterthought, an additional detail thrown in at the end of the discussion. IMHO, this is why MMT remains marginalized in much of radically progressive thought, is seen incorrectly but understandably as having little to say about profound systemic change, as being more focused on shoring up an ecocidal capitalist system than on fundamentally challenging and changing it.

@ Patrick B

“…antisemitism from Labour’s much enlarged Corbyn led leadership…”

I don’t follow your train of thought as written. Did you mean to write “membership” (not “leadership”)?

@ Derek Henry

Thank you very much for that superb exposition, so clear that even I can follow it (I think).

2.5% sounds like luxury from a federal public service view.

More like the total increase over the life of the current government.

Add in staffing caps and efficiency dividends….

Jobs and growth.

@robertH Yes, you’ve correctly interpreted my tautology. I’m sure I intended to write, ‘enlarged Corbyn led membership’.

@Derek Henry – yep, aware of all that. Just repeating the Central (Australian Reserve) Bank’s announcement that it intends to further support the non-monetarily sovereign Australian state and territory governments by purchasing more of their debt. And that it will further increase the amount that the left pocket of the federal government owes to the right pocket of the federal government, as Bill would say. Clearly demonstrating that there is no need for people to be hyperventilating over our governments debt and deficit. Cheers.

Full agreement with Newton Finn.

Leaving the bourgeois and their middle class accomplices unchallenged is not the way.

At the risk of seeming like an extremist, the picture we have is clear. The contradiction/conflict between bourgeois and working people can be resolved in either ecological disaster/extinction or revolution.

“It’s a safe investment, a store of wealth”

And, importantly, a store of taxation. bonds are a tax battery. When they are finally spent they release taxation.

Newton Finn.

The band is still playing as the Titanic sinks?

“Chris Williamson

@DerbyChrisW

29 Oct

Despite cries about ‘institutional anti-Semitism’ and an ‘existential threat to British Jews’, the EHRC based its report on a tiny sample of 70 complaints made over a three-year period.

It only found two examples of supposed ‘unlawful harassment’ – out of half a million members.”