Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – December 14-15, 2019 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The use of a fiscal surplus to create a sovereign fund provides a currency-issuing government with greater spending capacity in the future.

The answer is False.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) the national government’s ability to make timely payment of its own currency is never numerically constrained by revenues from taxing and/or borrowing. Therefore the creation of a sovereign fund by purchasing assets in financial markets in no way enhances the government’s ability to meet future obligations. In fact, the entire concept of government pre-funding an unfunded liability in its currency of issue has no application whatsoever in the context of a flexible exchange rate and the modern monetary system.

The misconception that ‘public saving’ is required to fund future public expenditure is often rehearsed in the financial media. In rejecting the notion that public surpluses create a cache of money that can be spent later we note that Government spends by crediting an account held by the commercial banks at the central bank.

There is no revenue constraint.

Government cheques don’t bounce!

Additionally, taxation consists of debiting an account held by the commercial banks at the central bank.

The funds debited are accounted for but don’t actually go anywhere nor accumulate.

Thus is makes no sense to say that a sovereign government is saving in its own currency. Saving is an act that revenue-constrained households do to enhance their future consumption opportunities. The sacrifice of consumption now provides more funds in the future (via compounding). But the government doesn’t have to sacrifice spending now to spend in the future.

The concept of pre-funding future liabilities does apply to fixed exchange rate regimes, as sufficient reserves must be held to facilitate guaranteed conversion features of the currency. It also applies to non-government users of a currency. Their ability to spend is a function of their revenues and reserves of that currency.

So at the heart of the mis-perceptions about sovereign funds is the false analogy mainstream macroeconomics draws between private household budgets and the government fiscal state.

Households, the users of the currency, must finance their spending prior to the fact. However, government, as the issuer of the currency, must spend first (credit private bank accounts) before it can subsequently tax (debit private accounts).

Government spending is the source of the funds the private sector requires to pay its taxes and to net save and is not inherently revenue constrained.

However, trying to squeeze the economy to generate these mythical “pools of funds” which are then allocated to the sovereign fund as if they exist is very damaging. You can think of this in two stages.

First, the national government spends less than it taxes and this leads to ever decreasing levels of net private savings (unless there is a strong positive net exports response).

The private deficits are manifest in the public surpluses and increasingly leverage the private sector. The deteriorating private debt to income ratios which result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing demand-draining fiscal drag through a slow-down in real activity.

Second, while that process is going on, the Federal Government is actually spending an equivalent amount that it is draining from the private sector (through tax revenues) in the financial and broader asset markets (domestic and abroad) buying up speculative assets including shares and real estate.

Accordingly, creating a sovereign fund amounts to the government competing in the private equity market to fuel speculation in financial assets and distort allocations of capital.

However, as you can see from pulling it apart, this behaviour has been grossly misrepresented as providing “future savings”. Say the sovereign government ran a $15 billion surplus in the last financial year. It could then purchase that amount of financial assets in the domestic and international capital markets. But from an accounting perspective the Government would no longer have run that surplus because the $15 billion would be recorded as spending and the fiscal position would break even.

In these situations, the public debate should be focused on whether this is the best use of public funds. It would be hard to justify this sort of spending when basic infrastructure provision and employment creation has been ignored for many years by neo-liberal governments.

So all we are talking about is a different portfolio of assets.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

Question 2:

If employment growth matches the pace of growth in the working age population (people above 15 years of age) then the economy will experience a constant unemployment rate as long as participation rates do not change.

The answer is True.

The Civilian Population is shorthand for the working age population and can be defined as all people between 15 and 65 years of age or persons above 15 years of age, depending on rules governing retirement. The working age population is then decomposed within the Labour Force Framework (used to collect and disseminate labour force data) into two categories: (a) the Labour Force; and (b) Not in the Labour Force. This demarcation is based on activity principles (willingness, availability and seeking work or being in work).

The participation rate is defined as the proportion of the working age population that is in the labour force. So if the working age population was 1000 and the participation rate was 65 per cent, then the labour force would be 650 persons. So the labour force can vary for two reasons: (a) growth in the working age population – demographic trends; and (b) changes in the participation rate.

The labour force is decomposed into employment and unemployment. To be employed you typically only have to work one hour in the survey week. To be unemployed you have to affirm that you are available, willing and seeking employment if you are not working one hour or more in the survey week. Otherwise, you will be classified as not being in the labour force.

So the hidden unemployed are those who give up looking for work (they become discouraged) yet are willing and available to work. They are classified by the statistician as being not in the labour force. But if they were offered a job today they would immediately accept it and so are in no functional way different from the unemployed.

When economic growth wanes, participation rates typically fall as the hidden unemployed exit the labour force. This cyclical phenomenon acts to reduce the official unemployment rate.

So clearly, the working age population is a much larger aggregate than the labour force and, in turn, employment. Clearly if the participation rate is constant then the labour force will grow at the same rate as the civilian population. And if employment grows at that rate too then while the gap between the labour force and employment will increase in absolute terms (which means that unemployment will be rising), that gap in percentage terms will be constant (that is the unemployment rate will be constant).

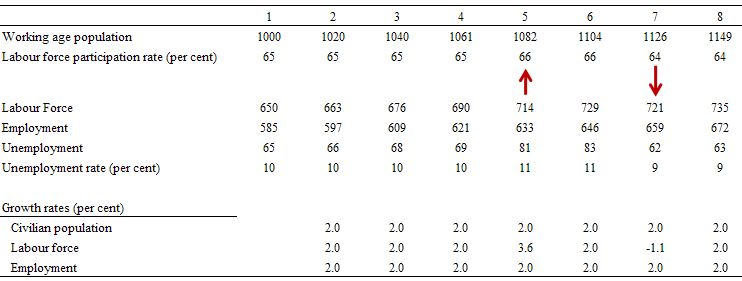

The following Table simulates a simple labour market for 8 periods. You can see for the first 4 periods, that unemployment rises steadily over time but the unemployment rate is constant. During this time span employment growth is equal to the growth in the underlying working age population and the participation rate doesn’t change. So the unemployment rate will be constant although more people will be unemployed.

In Period 5, the participation rate rises so that even though there is constant growth (2 per cent) in the working age population, the labour force growth rate rises to 3.6 per cent. Now unemployment jumps disproportionately because employment growth (2 per cent) is not keeping pace with the growth in new entrants to the labour force and as a consequence the unemployent rate rises to 11 per cent.

In Period 6, employment growth equals labour force growth (because the participation rate settles at the new level – 66 per cent) and the unemployment rate is constant.

In Period 7, the participation rate plunges to 64 per cent and the labour force contracts (as the higher proportion of the working age population are inactive – that is, not participating). As a consequence, unemployment falls dramatically as does the unemployment rate. But this is hardly a cause for celebration – the unemployed are now hidden by the statistician “outside the labour force”.

Understanding these aggregates is very important because as we often see when Labour Force data is released by national statisticians the public debate becomes distorted by the incorrect way in which employment growth is represented in the media.

In situations where employment growth keeps pace with the underlying population but the participation rate falls then the unemployment rate will also fall. By focusing on the link between the positive employment growth and the declining unemployment there is a tendency for the uninformed reader to conclude that the economy is in good shape. The reality, of-course, is very different.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

In a fiat monetary system with an on-going external deficit, the domestic private sector cannot save overall, if the national government runs a fiscal deficit.

The answer is False.

This question is an application of the sectoral balances framework that can be derived from the National Accounts for any nation.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAB > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAB < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

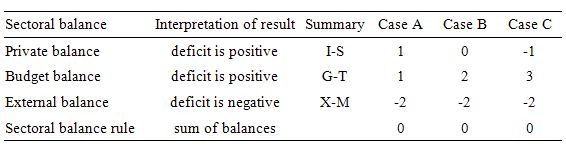

To help us answer the specific question posed, we can identify three states all involving public and external deficits:

- Case A: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) < Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case B: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) = Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

- Case C: Fiscal Deficit (G – T) > Current Account balance (X – M) deficit.

The following Table shows these three cases expressing the balances as percentages of GDP. Case A shows the situation where the external deficit exceeds the public deficit and the private domestic sector is in deficit. In this case, there can be no overall private sector saving.

With the external balance set at a 2 per cent of GDP, as the government moves into a larger deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance (Case B). Case B also does not permit the private sector to save overall.

Once the fiscal deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).

In this situation, the fiscal deficits are supporting aggregate spending which allows income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector but have to be able to offset the demand-draining impacts of the external deficits to provide sufficient income growth for the private domestic sector to save.

For the domestic private sector (households and firms) to reduce their overall levels of debt they have to net save overall. The behavioural implications of this accounting result would manifest as reduced consumption or investment, which, in turn, would reduce overall aggregate demand.

The normal inventory-cycle view of what happens next goes like this. Output and employment are functions of aggregate spending. Firms form expectations of future aggregate demand and produce accordingly. They are uncertain about the actual demand that will be realised as the output emerges from the production process.

The first signal firms get that household consumption is falling is in the unintended build-up of inventories. That signals to firms that they were overly optimistic about the level of demand in that particular period.

Once this realisation becomes consolidated, that is, firms generally realise they have over-produced, output starts to fall. Firms lay-off workers and the loss of income starts to multiply as those workers reduce their spending elsewhere.

At that point, the economy is heading for a recession.

So the only way to avoid these spiralling employment losses would be for an exogenous intervention to occur. Given the question assumes on-going external deficits, the implication is that the exogenous intervention would come from an expanding public deficit. Clearly, if the external sector improved the expansion could come from net exports.

It is possible that at the same time that the households and firms are reducing their consumption in an attempt to lift the saving ratio, net exports boom. A net exports boom adds to aggregate demand (the spending injection via exports is greater than the spending leakage via imports).

So it is possible that the public fiscal balance could actually go towards surplus and the private domestic sector increase its saving ratio if net exports were strong enough.

The important point is that the three sectors add to demand in their own ways. Total GDP and employment are dependent on aggregate demand. Variations in aggregate demand thus cause variations in output (GDP), incomes and employment. But a variation in spending in one sector can be made up via offsetting changes in the other sectors.

So given that the fiscal deficit has to be larger than the external deficit, the best answer is maybe.

The following blog posts may be of further interest to you:

- Private deleveraging requires fiscal support

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Saturday Quiz – May 22, 2010 – answers and discussion

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m sure that Bill will wade in on the results of the UK election, but has there ever been a clearer demonstration of the hard truths he and Tom put forward in “Reclaiming the State?”

Answer to question 3; sentence below accounting identity (6): I do not understand the part “…. and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.” Does “equal” refer to the amount? Why “opposite sign”? Private saving can only occur in this identity if government spending exceeds taxes meaning both sides should show the same sign.

Non Economist @4:51,

You are correct that both sides of the equation when solved, show the same sign. But when G-T is a negative number the government’s fiscal balance is said to be in surplus. And when G-T is a positive number, then the balance is called a deficit. So the government’s ‘financial balance’ will always be the opposite sign of G-T. It gets a bit confusing sometimes…

Also it is possible for the government to have a surplus and for the private domestic sector to save in terms of net financial assets if the Current Account Balance is more ‘positive’ than G-T is ‘negative’.

Three out of three for me!

Can’t wait for Bill’s analysis of the British Election.

Clearly, Labour’s ambiguous Brexit stance was a real turn off fro traditional Labour voters, but its disappointing to hear those same voters didn’t believe that the spending promises made by Labour were “unaffordable” too!

Any electorate will need to be “educated” very carefully before it embraces the policy freedom accorded by MMT insights, or the Tories will simply pick progressives off with the “how are you going to pat for it” line.

Sorry for the unintended double negative

I meant didn’t believe the spending promises were affordable.