I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The challenges of labour underutilisation and low wages

Today I am a keynote speaker at the LHMU National Conference in Canberra. I am talking about the challenges of underemployment and low wages and the need for the union movement to broaden out their activism from narrow concerns about wages and conditions for their members to development and pursuit of a full-scale attack on neo-liberalism. In much the same way that the neo-liberal think tanks boosted the saturation of those ideas. I will report back when I get back – much later this evening.

As promised my talk to the LHMU National Conference in Canberra today was based on a slide show which you can download from HERE.

I started my talk today by arguing that the macroeconomics debate lies at the heart of the problems facing low wage workers and the unemployed. That has to be dealt with head-on or we will just be tinkering around the edges.

Unless the unions challenge the neo-liberal macro myths they will be confined to fighting narrow battles and face continual squeezing on their capacity. They will certainly never resume the role as key agents for progressive change – a capacity that was exemplified during the days of the Green Bans, to give one example.

I made the point that the neo-liberal agenda has been very successful in developing the notion that the government budget is akin to a household budget by creating and funding a host of supportive think tanks. These organisations have refined their marketing and publication capacities and can always attract public attention. They are also very effective lobbying organisations. The progressive side of the debate has been divided and poorly organised.

In this regard I argued that there is an urgent need to develop a macroeconomic narrative which can permeate the public debate and redefine how we see government and what goals we want government to pursue. The unions have not developed a narrative beyond their narrow wages and conditions focus. I see that the challenge for the union movement, especially those that are representing low wage workers who are most exposed to casualisation and job loss, is to develop this narrative and build supportive (think tank) capacity to perpetuate it.

I then discussed basic modern monetary theory with the participants. The standard fundamentals:

- Production levels are based on aggregate demand – spending and employment is created to generate output to meet the demand for it. This generates income which is consumed or saved and saving constitutes a “leakage” from the spending-output system. This is what we call the spending gap and if it remains unfilled then output and employment fall.

- The responsibility of fiscal policy is to fill this spending gap.

- Crucially, the Federal Government is never revenue-dependent in a fiat monetary system. There is no such thing as the government “running out of money” which is not the same thing as saying the government should spend infinitely. The responsibility of the government is to fill the spending gap and balance nominal spending growth with the real capacity of the economy to absorb it.

- Taxation do not raise funds for government – it destroys spending capacity in the private sector!

- Issuing government debt does not raise funds for government – it takes funds from the private sector! Budget deficits drive interest rates down!

- Budget surpluses increasethe spending gap (fiscal drag). Other things equal, this means the private sector has less to spend than otherwise. There is less private employment. There is less public employment. There is less public infrastructure investment. There is less education and training provided. There are less public services and less scope for income support.

At that point, I revealed my Japan slide and said:

If you believe the neo-liberal line – how do you explain Japan?

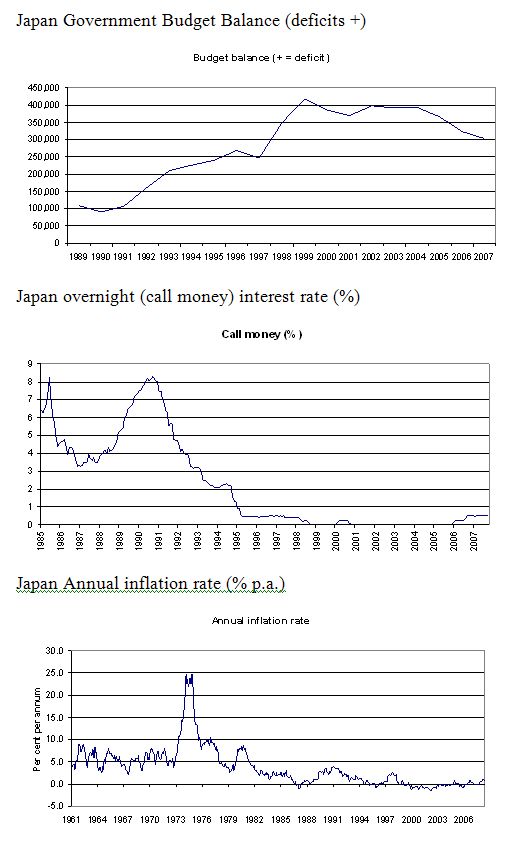

The following graphs appear on my Japan slide. Print it and carry it with you so that if you have the misfortune of running into a neo-liberal you can get them to take out their macroeconomic textbooks and explain what is going on.

It shows the budget deficit (top graph) up 2008 (nothing is gained by adding recent data although next time I do it I will update it). The deficit grew after the 1991 downturn to ensure that the rising desire to save by the private sector at the time didn’t absolutely scorch the economy. As it was, growth was poor and unemployment rose a little signifying that the deficits actually sustained were not large enough. But the deficits did provide some underwriting for production and employment levels. Even at the height of their crisis, official unemployment was well below the levels that the west succumbed to during the various crises over the last 35 years.

The second graph (middle) shows the evolution of the call rate (the short-term interest rate under the control of the Bank of Japan) over the same period. Zero interest rates were maintained for most of this period. How could that be with such consistent budget deficits? Don’t budget deficits cause interest rates to rise? Obviously not! A modern monetary theorist will easily explain this as follows.

The Bank of Japan was issuing large volumes of government debt during this time not to fund the deficits but to give it control over the interest rate. Remember the non-government sector cannot purchase government paper before there are reserve balances created to provide the funds. You cannot get these reserve balance unless there has been prior deficit spending or the private sector has borrowed from the government (typically via the central bank). The Bank of Japan issued just enough debt to leave excess reserves in the monetary system.

This deliberate strategy allowed interbank competition to drive the interbank interest rate to zero meaning the Bank of Japan could maintain its chosen zero interest rate strategy. Under a flexible exchange rate regime, the call rate becomes a policy variable (set by the central bank).

Further, given the excess capacity in the Japanese economy, the net spending engendered by the deficits were not inflationary. Graph 3 shows that over this period, Japan struggled against deflation.

You might like to review the blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy.

I then showed a series of graphs – unemployment, underemployment, real wages falling way behind productivity growth, the decimation of the wage share, the growth in household debt to make the case that the neo-liberal program had failed to deliver anything other than crisis and misery to the low-wage workers and the unemployed. You can see these graphs in the downloaded slide show (see above).

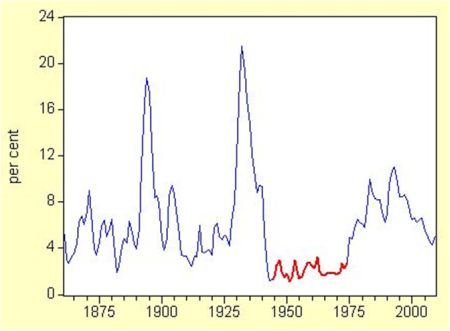

I also discussed the following graph which is the Australian official unemployment rate since 1861. The bolded red segment is the period when our federal government took responsibility for ensuring that there were enough jobs – not helping everyone get skills – but providing enough jobs. The periods outside of the red segment were when there was no such commitment and employment levels were essentially determined by the private market. In the most recent period, the federal government has actually been withdrawing as an employer.

Certain countries were able to avoid the rise in unemployment that beset most OECD countries after the mid-1970s. The private sector (and career public sector) has never provided enough jobs to full employ the available labour supply. The only reason we enjoyed the full employment period (red segment) was because the Australian public sector maintained a “buffer stock of jobs” which were accessible to the most disadvantaged workers any day of the week they needed to find work.

The effectiveness of this capacity was profound and ensured that the least skilled and troubled workers could still work and earn an income. It ensured they were not socially alienated by unemployment.

This buffer stock capacity forms the conceptual basis of my Job Guarantee proposal. We desperately need to restore this capacity and only the federal government can do that – given it has the fiscal capacity to do so.

This capacity was lost once the neo-liberals started influencing policy and wound back the sections of the public sector that provided these jobs. So the privatisation and out-sourcing that went on in the 1980s and since killed off many opportunities to create public sector work for the disadvantaged. National competition policy throttled the capacity of local governments to provide jobs for their citizens. And the fetish about budget surpluses ensured that governments cut overall public employment in the false belief that this was the path to prosperity.

That is why we now have a buffer of unemployed who are used by the central bank and Treasury in their fight against inflation. Unemployment has become a policy tool rather than a policy target. The neo-liberals then built an industry around unemployment which was filled with all sorts of parasites intent on getting their hands on lucrative government contracts to provide privatised labour market services. But not a job was created by this “supply-side” punishment regime. The unemployment were made to jump through rings and fined and punished if they didn’t scrub up in the way the government expected. But not a job was created.

I also reaffirmed by definition of full employment – less than 2 per cent official unemployment (for people moving between jobs during the survey week); zero underemployment; and zero hidden unemployment.

The way forward

The reason why Governments were able to maintain buffer stock employment capacity is because they were supported by the community. This was an era of collective will which has been lost during the neo-liberal years which have advanced the notion of the individual and individualism. This has had two consequences: (a) governments have become loath to take responsibility for full employment; and (b) in advancing the diminished goal of full employability – the supply-side agenda – they have built a myth that unemployment is an individual failing rather than a systemic (macroeconomic) failure that arises from deficient aggregate demand.

Building a macroeconomic narrative requires that public institutions such as the unions mount a challenge the neo-liberal budget austerity mantra and develop the essential understanding that if the non-government sector is to save then the government has to be in deficits. That is the only basis for sustainable growth with full employment.

I see a Job Guarantee as being an essential part of this strategy – it is not a panacea for everything. It is actually a modest step to provide the safety net. The fact that the critics see it as an extreme measure tells you how far the debate has swung away from the debate which was conditioned by collective will. It is also a denial of the essential capacities of a government in a fiat monetary system.

A further campaign that progressives have to pursue is to broaden what we mean by productive work. A productive contribution has to be seen in terms of how well society benefits not how well the private profit line is enhanced. In general, the two aims will not be counter to each other but sometimes they will and the priority has to be on the collective rather than the corporate.

The full employment campaign ties in closely with the development of a minimum wage framework. The determination of the minimum wage should not be based on private employer capacity to pay considerations. They are irrelevant in my opinion to the question of what a minimum wage should be.

We have to calibrate the wage structure by setting a floor that means something in terms of our aspirations for a decent life. If the capitalist cannot profitably organise production at that wage then we are saying that we do not want them operating in this country.

I see this as an essential message for the unions that cover low wage workers such as the LHMU to be making.

The introduction of a Job Guarantee would also fundamentally change the dynamics of the minimum wage debate and wage bargaining by unions representing low-wage workers. The Job Guarantee would set the wage floor and provide income security for low wage and otherwise disadvantaged workers. These workers would always know that they could get meaningful and useful work within the Job Guarantee without the threats that arise from low pay and precarious work.

Those threats would lose currency. Private employers would be forced to restructure their own workplaces to ensure they provided superior conditions to the Job Guarantee if they wanted to attract work. The dialogue that the union would then have with those employers would be conditioned by this new reality and would lead to new dynamic efficiencies which would benefit the low paid workers but also the economy in general.

I see this as a fundamental outcome of successfully pursuing an effective macroeconomics narrative.

Conclusion

I argued that the only way the unions will reclaim their place as the central agents for effective progressive reform is to advance a new macroeconomic narrative. I consider that the unions have failed in this regard and have been co-opted by successive governments into accepting legislation that has severely restricted their capacity to be agents of change..

I consider a national education campaign to be an essential part of the narrative – to disabuse the public of the myths that have been used to erode notions of collective will.

I also think that it is essential that capacity be built both within and outside the union movement to achieve this – this is what I called the think tank approach.

I also think progressives should not vote for any government that advances ideology that is contrary to the collective will. That means not contributing funds to parties that perpetuate neo-liberal ideology. Governments that abandon full employment and then punish the victims of this policy failure including low wage workers cannot be supported.

I concluded by reasserting that the Federal government must run deficits as a normal consequence of the desire by the private sector to save.

I also argued that reeal wages must grow in proportion to productivity and reverse the trend that has developed as the government has weakened unions and deregulated the labour market. I consider there has to be a major redistribution of income away from profits towards wages so that production growth doesn’t rely on households building ever-increasing levels of debt.

I finished by saying that governments must ensure that there are enough jobs available by increasing its role as a direct employer. That is the first thing they should do.

I will be interested in your report Bill. The LHMU have a fairly strong presence in my workplace ( I am a member of a different union).

Most union members don’t see unions as agents for political/socio/economic change any more. They veiw them as something akin to an insurance company. You pay them a regular retainer and have nothing else to do with them until you get in the shit.

At the last meeting I attended, the organiser introduced himself and proceeded to describe what a union was (there were some interested non-members present). He summed it up as being no different to a group of mine owners who meet regularly to discuss how they can get a better price for their coal by acting together. “It’s just about getting the best money for our members – it’s not about red-raggers anymore”, he declared.

When the union movement has become little more than a conglomeration of insurance companies, then it has lost it’s soul as far as I am concerned.

The unions are trying to regain flagging membership by trying to appeal to a lumpen proletariat. The average Australian of today is not remotely interested in working towards a better, fairer world for all. Their sole concern is maximising their own individual self-interest. Collective conciousness has largely disappeared. I don’t think that this is a permanent situation but we are definately living in an age dominated by self-centredness.

“It doesn’t matter to me,

It, doesn’t matter to me,

I’ll sit sit home and watch youse all on,

My colour t.v”

The purpose of unions is precisely “narrow concerns about wages and conditions”, because those narrow concerns are what unites its members. Union funds are not there to promote the ideological posturing of the union’s officers, and if so used will cause those funds to diminish. Many years ago I resigned from a union position because the union proposed to spend almost a year’s worth of dues on a campaign for abortion on demand. I actually agree with abortion on demand, but this would have been a disaster for the union – most of its Catholic members would have left, for a start. Just as on the other side the shoppies union still can’t get women to join it (and still can’t get pay rises either, not coincidentally).

Underemployment can never go to zero, for the same sort of reason unemployment cannot go to zero. There will always be some people whose hours don’t really suit them but for whom, even in a white-hot labour market, its not worth changing jobs; that sort of insight is what underlays the whole employer monopsony stuff that you cite in other contexts. Mark Wooden, IIRC, used the HILDA survey to show that the great majority of those working part time and wanting more hours wanted less than 4 hours more a week. This is not to deny that the recent rise in underemployment represents a real welfare loss (though not as much of a one as an equivalent rise in unemployment would), but ya gotta be realistic.

Can’t have been that many years ago DD because many years ago, things were somewhat different.

Hi Bill,

Really appreciated your presentation this week.

Apart from occasionally being quite confused and thinking ‘i really should read this guy’s blog and try to get to grips with what he’s saying’, what most impressed me was the discussion your presentation generated amongst the delegates. The large group of rank and file delegates at the conference came from a range of industries including aged care, child care, school cleaning, manufacturing, office cleaning and many many more. After you left the delegates broke into groups to discuss the concepts you had put forward and their potential application within union plans & strategy and within delegates’ industries.

It was clear from the discussion, debate and general calibre of conversation that people were engaged, inspired and (most importantly) motivated to do something. They all certainly came to the conference understanding what the global financial crisis and climate change means for low wage workers – more sacrifices for them and their workmates. What they left with were some compelling ideas that contradict established economic orthodoxy and, along with putting forward recommendations about how to use your ideas within the union as a whole, they planned to educate delegates and members back in their cities about what they’d learnt.

Some people on your blog have commented on the ability of unions to engage with more than narrow concerns about wages and money. Though I agree that unions sometimes struggle to develop the analysis and narrative to step outside of this paradigm, some, including the delegates you spoke to this week, are definitely out there trying – because they want to, but also because they have to.

Thanks for adding to the analysis.

I completely agree with your conclusion Bill.