I grew up in a society where collective will was at the forefront and it…

US growth robust but doubts remain

Last Friday (October 26, 2018), the US Bureau of Economic Analysis published their latest national accounts data – Gross Domestic Product, 3rd quarter 2018 (advance estimate) , which tells us that the annualised real GDP growth rate for the US remains strong at 3.5 per cent (down from 4.2 per cent in the June-quarter 2018). Note this is not the annual growth over the last four-quarters, which is a more modest 3 per cent (up from 2.9 per cent in the previous quarter). As this is only the “Advance estimate” (based on incomplete data) there is every likelihood that the figure will be revised when the “second estimate” is published on November 28, 2018. The US result was driven by a growing household consumption contribution (2.7 points) with the personal saving rate falling by 0.4 points. Further, the government spending contribution was also strong (0.6 points up from 0.4) with all levels of government recording positive contributions. Real disposable personal income increased 2.5 percent, the same increase as in the second quarter. While private investment was strong it was mostly due to unsold goods (inventories). Notwithstanding the strong growth, the problems for the US growth prospects are two-fold: (a) How long can consumption expenditure keep growing with slow wages growth and elevated personal debt levels? Most of the consumption growth is coming because more people are getting jobs even though wages growth is flat. (b) What will be the impacts of the current trade policy? It is a work in progress.

Press Response

The Wall Street Journal article (October 26, 2018) – 3% Growth, If We Can Keep It – which responded to the BEA data release was a mixture of falsehoods and truths.

By way of falsehood, the WSJ said that:

It’s clear that the Republican policy mix of tax reform, deregulation and general encouragement for risk-taking rescued an expansion that was fading fast and almost fell into recession in the last six quarters of the Obama Administration. The nearby chart tells the story that Mr. Obama and his economists won’t admit. Soaring business and consumer confidence have been central to this rebound.

The ‘Chart’ in question was just the Quarterly percent change in GDP from Q3 in 2015 to Q3 this year (see below for my version of the graph).

As you will see below, the data does not support the claim that business has rebounded because of a “mix of tax reform, deregulation and general encouragement for risk-taking”.

Most of the growth came from household consumption expenditure with solid contributions from the government sector. While the contribution from private capital formation was strong, it was mostly due to unsold goods (inventories) with fixed investment and residential investment dragging down growth.

This is contrary to the narrative that the WSJ is trying to confect.

In assessing the WSJ’s claim that consumer and business confidence has risen due to Trump’s policy stance, we can consult the Conference Board Measures of Consumer and CEO confidence.

The Conference Board Measure of CEO Confidence showed a continued decline in this measure since the March-quarter and “is now at its lowest level in two years” falling by 0.8 points in the September-quarter.

In contrast, The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index increased in the September-quarter by 3.7 points.

By way of truth, the WSJ said that:

All the more so because Mr. Trump may soon face an economic challenge from a Democratic House, if not Senate. A tax increase would be near the top of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s policy list, and she might use the need to raise the federal debt limit in 2019 to force Mr. Trump’s hand.

The Democratic obsession with ‘sound finance’ and its continual railing against the fiscal deficit and public debt is a massive danger to US growth, especially when one considers the point I noted before that the growth is being driven by the rising debt in an environment of flat business investment.

Seriously, the Democrats need to really rethink their approach.

US economy – what is going on at the aggregate level?

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis said that:

Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at an annual rate of 3.5 percent in the third quarter of 2018 … In the second quarter, real GDP increased 4.2 percent.

Note that the BEA is using the annualised quarterly figure here (multiplying the September-quarter growth by 4) rather than the actual annual (year-on-year) growth rate which is the percentage shift from the September-quarter 2017 to the September-quarter 2018.

That growth figure was 3.04 per cent, up from 2.87 per cent in the June-quarter although the quarter-on-quarter growth outcome of 0.86 per cent was down on the June-quarter result of 1.02 per cent.

The following sequence of graphs captures the story.

The first graph shows the annual real GDP growth rate (year-to-year) from the peak of the last cycle (December-quarter 2007) to the June-quarter 2018 (grey bars) and the quarterly growth rate (blue line). Note the date line starts at December-quarter 2007.

The year-to-year growth calculation smooths out the considerable volatility in the quarterly data to help us see the trend.

There is now growing momentum in US growth in terms of the annual growth rate (year-on-year).

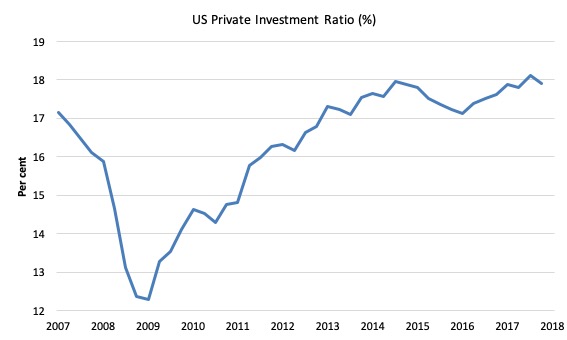

The next graph shows the evolution of the Private Investment to GDP ratio from the December-quarter 2007 (real GDP peak prior to GFC downturn) to the September-quarter 2018. Note the date line starts at December-quarter 2007.

The decline in the investment ratio as a result of the crisis was substantial and endured for 2 years. As a result the potential productive capacity of the US contracted somewhat. There are various estimates available but the overall message is that potential GDP fell considerably as a result of the lack of productive investment in the period following the crisis.

The retreat in the Investment ratio after the June-quarter 2015, appears to have been arrested and while the ratio is trending upwards, it fell from 18.1 per cent in the June-quarter to 17.9 per cent in the September-quarter 2018.

In this blog post – Common elements linking US and UK economic slowdowns – I discuss estimates of potential GDP in the US and the shortcomings of traditional methods used by institutions such as the Congressional Budget Office.

So if you are interested please go back and review that discussion.

The latest CBO estimates, made available through – St Louis Federal Reserve Bank, show why we should be skeptical.

To get some idea of what has happened to potential real GDP growth in the US, the next graph shows the actual real GDP for the US (in $US billions) and two estimates of the potential GDP. There are many ways of estimating potential GDP given it is unobservable.

While I could have adopted a much more sophisticated technique to produce the red dotted series (potential GDP) in the graph, I decided to do some simple extrapolation instead to provide a base case.

The question is when to start the projection and at what rate. I chose to extrapolate from the most recent real GDP peak (December-quarter 2007). This is a fairly standard sort of exercise.

The projected rate of growth was the average quarterly growth rate between 2001Q4 and 2007Q4, which was a period (as you can see in the graph) where real GDP grew steadily (at 0.65 per cent per quarter) with no major shocks.

If the global financial crisis had not have occurred it would be reasonable to assume that the economy would have grown along the red dotted line (or thereabouts) for some period.

The gap between actual and potential GDP in the September-quarter 2018 is around $US2,186 billion or around 10.5 per cent.

That gap rose steadily since late 2014 but then stabilised and has been declining since the March-quarter 2018.

In the September-quarter 2018, it fell by 0.2 points as a result of the stronger growth.

The green dotted line is the estimate of potential output provided by the US Congressional Budget Office and made available through – St Louis Federal Reserve Bank.

In relation to the CBO estimate, the US economy is estimated to be operating at 6.2 per cent over its potential in the June-quarter 2018.

It is hard to believe the estimate!

As a hint, the BEA report for the National Accounts release notes that:

The price index for gross domestic purchases increased 1.7 percent in the third quarter, compared with an increase of 2.4 percent in the second quarter … The PCE price index increased 1.6 percent, compared with an increase of 2.0 percent. Excluding food and energy prices, the PCE price index increased 1.6 percent, compared with an increase of 2.1 percent.

That is, price pressures declined, hardly symptomatic of an economy that is operating at 6.2 per cent over its capacity.

Further, wages growth remains flat and broader measures of labour underutilisation indicate there is still considerable slack.

Which suggests that the CBO estimates are inaccurate – probably by several percentage points.

We know (and I explain this in more detail in the blog post mentioned above), the CBO base their estimate of Potential GDP on their estimate of the NAIRU – the (unobservable) Non-accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment.

This is a conceptual unemployment rate that is consistent with a stable rate of inflation.

The literature demonstrates that the history of NAIRU estimation is far from precise. Studies have provided estimates of this so-called ‘full employment’ unemployment rate as high as 8 per cent or as low as 3 per cent all at the same time, given how imprecise the methodology is.

The former estimate would hardly be considered “high rate of resource use”. Similarly, underemployment is not factored into these estimates.

The continued slack in the labour market (bias towards low-pay and high underemployment) would lead to the conclusion that the output gap is likely to be somewhat closer to the extrapolated estimate than the CBO estimate.

The question to ask is this: How much lower would the unemployment rate and the broader underutilisation rate go if the US federal government offered a Job Guarantee on an unconditional basis?

I would bet the answer would be much lower without any inflation acceleration emerging.

Contributions to growth

The accompanying BEA Press Release said that:

The increase in real GDP in the third quarter reflected positive contributions from personal consumption expenditures (PCE), private inventory investment, state and local government spending, federal government spending, and nonresidential fixed investment that were partly offset by negative contributions from exports and residential fixed investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased (table 2).

The deceleration in real GDP growth in the third quarter reflected a downturn in exports and a deceleration in nonresidential fixed investment. Imports increased in the third quarter after decreasing in the second. These movements were partly offset by an upturn in private inventory investment.

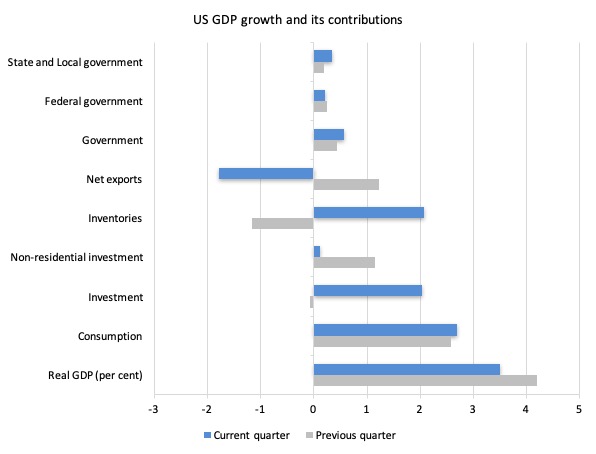

The next graph compares the September-quarter 2018 (blue bars) contributions to real GDP growth at the level of the broad spending aggregates with the June-quarter 2018 (gray bars).

Household consumption expenditure continues to be the strongest positive contributor rising from 2.57 points to 2.69 points in the September-quarter 2018.

With household debt remaining high (see below) and real wages growth sluggish it remains to be seen how long household consumption can maintain this impetus.

Most of the consumption growth is coming because more people are getting jobs even though wages growth is flat. This cannot persist obviously.

Gross private domestic investment also contributed 2 points to growth but most of that was from the Change in Private inventories (unsold goods).

Household investment fell for the third straight quarter.

The Government sector added 0.6 points to the September-quarter 2018 growth up from 0.4 points in the previous quarter.

That contribution was spread between the Federal government (0.21 points down from 0.24 points) and State and Local government (0.35 points up from 0.24 points).

Net exports undermined growth (-1.78 points down from 1.22 points). This is almost certainly the impact of tariff increases with exports alone cutting 0.45 points from the current quarter’s growth.

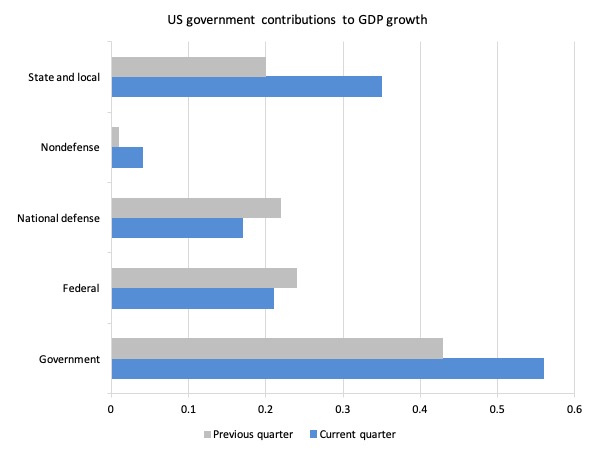

The next graph decomposes the government sector and shows that all levels of government contributed significantly to growth in the current-quarter and increased the contribution relative to the previous-quarter.

The federal contribution was, however, dominated by the strong military expenditure while reducing the contribution of non-defense spending.

That has been a trend under the current Presidency – a worrying sign.

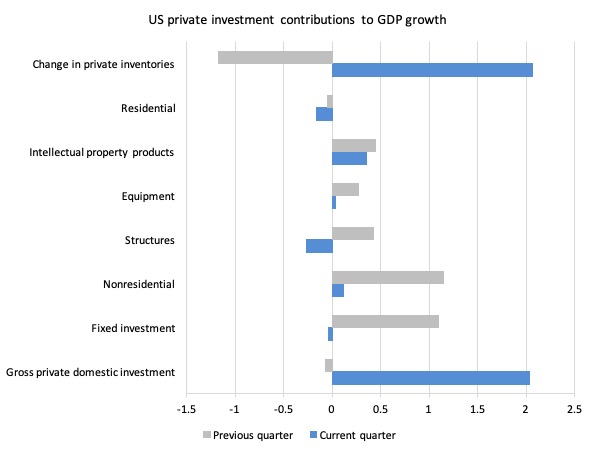

The next graph shows the contributions to real GDP growth of the various components of investment.

The inventory cycle dominated other positive investment contributions.

Household consumption and debt

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York publication – Household Debt and Credit Report – was last updated for the second-quarter 2018 – (PDF Download).

It shows:

total household debt reached a new peak in the second quarter of 2018, rising by $82 billion to reach $13.29 trillion. Mortgage balances, the largest component of household debt, rose to a total of $9 trillion during the second quarter. Auto loan balances increased by $9 billion to reach $1.24 trillion, continuing a six-year upward trend …

Aggregate household debt balances increased in the second quarter of 2018 for the 16th consecutive quarter, and are now $618 billion higher than the previous (2008Q3) peak of $12.68 trillion. As of June 30, 2018, total household indebtedness was $13.29 trillion, an $82 billion (0.6%) increase from the first quarter of 2018. Overall household debt is now 19.2% above the 2013Q2 trough.

The question that remains unanswered is whether US households will be able to maintain consumption spending growth given the rising household debt levels.

Is the significant slowdown in consumption spending growth a sign that a peak debt level is approaching?

The following graph is taken from the FRBNY publication. Clearly the gap between mortgage and non-mortgage debt is rising as total household indebtedness rises.

This looks to be an unsustainable situation and will require either significant non-government spending boosts in investment or net exports or government spending increases to offset the likely slowdown in household consumption spending.

Conclusion

The continued growth in the September-quarter 2018 was down to strengthening household consumption spending, largely the result of a slight rundown in savings and the fact that more people are getting jobs.

Even though wages growth is flat the fact that more people are working means that spending growth can be maintained.

But that source of growth is finite and eventually the record levels of household indebtedness combined with the flat wages profile will bring it to an end.

Whether the rise in inventories is a negative will be seen in the next few quarters.

The tariff war is probably impacting now on exports which detracted from growth.

Further, the government spending contribution was also strong (0.6 points up from 0.4) with all levels of government recording positive contributions.

That impetus is being challenged by the Democrat insistence that the Federal deficit be cut. Whether that happens will be influenced by the political events in the next few weeks.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The FED is already making noises about increasing interest rates.

The Donald has tried to dump cold water on them for it.

The roller coaster will continue until the politicians learn how the bills are paid. The university level textbook of MMT informed macro cannot come soon enough!

I’d like to point towards Prof. Micheal Hudson’s numerous statements, in which he postulates that the 2008 GFC was not “solved” but postponed and that almost all of the recovery has went directly into the profits of the FIRE sector (Finance, Insurances & Real Estate). He goes on to postulate that a massive haircut to privetely held debt is necessary in order to stop the economy from tanking yet again, but I just don’t see that happening anytime soon.

It is my understanding, that in MMT the Job Guarantee could ensure that at least the younger ones find a way out of “debtor’s prison” through a government job (adequately paid), but for older or disabled people, it would be of little help.

Does anyone know, if there is a good reason not to let the lenders bleed for reckless loans? Wouldn’t it also be possible from an MMT accounting perspective, that the government buys the most “toxic” loans from the banks that hold them at a discount rate and then simple nullify them or pass the savings on to the debtors? To me it kinda sounds doable and fair, instead of losing the whole value of the asset/loan when it defaults, the bank gets something back and debtors are relieved to either invest, consume or save more. Also, I have read of some banks doing this already, but selling the assets to loan shark enterprises, that harass the debtors to extract as much payment out of the loan as possible.

Your thoughts?

In the US, in the system we currently have, I think there is one good reason not to let the lenders ‘bleed out’ for reckless loans. And that is because the banks that make the loans are ‘systematically’ important to the way we currently run the payments system and unfortunately, the economy. Not that we couldn’t change that in the future, but right now, many banks have so many different obligations to make payments to each other, and to people in the general public that just allowing them to fail (even because of their own irresponsibility) could cause a lot of collateral damage. The federal government could assume the debt obligations of failing banks and pay them by creating money, but that probably would not seem all that fair. And the government could purchase the assets (the loans) from the holders and forgive those debts (or not) also, but there is the same problem about fairness. And actually, the federal government did some of both (up to $29 trillion’s worth according to Randy Wray) during the financial crisis through Federal Reserve actions and the TARP and Harp programs.

And I’m not sure there is anyone who thinks it was all that ‘fair’. I know I didn’t.

Anyways, all this is assuming the government issues its own currency and that the debts are in this currency. Since you write as HermannTheGerman, it is very possible that this does not apply to your own national government.

The Democratic obsession with ‘sound finance’ and its continual railing against the fiscal deficit and public debt is a massive danger to US growth, … Bill Mitchell

In addition to “corporate welfare”, as you’ve called it Bill, positive yields* on the inherently risk-free debt of a monetary sovereign like the US confuse people and politicians into thinking that the monetary sovereign must borrow its own fiat.

*Likewise, positive interest on inherently risk-free fiat account balances at the Central Bank are “corporate welfare” too. Indeed, given that fiat is owned by the monetary sovereign, banks and other large accounts may properly be charged “rent”, i.e. negative interest, for using fiat.

Adding:

How can we achieve maximum benefit (not to mention social justice) using inexpensive (as it should be) fiat with a system and policies that were designed or evolved for expensive fiat, i.e. for the Gold Standard?

“New wine requires new wine skins” Matthew 9:17-18.

Here is a copy of a rant I wrote on John Quiggin’s webesit. It refers to Australia but the critique of neoliberalism is of course relevant to all Anglophone countries these days.

“Hundreds of Centrelink call centre jobs to be privatised to reduce wait times, increase efficiency”

This is a news headline for the latest idea from our LNP Federal Govt. How many times have we heard the “privatise to increase efficiency (of public services)” mantra and how many times has it been wrong? Hint, these two numbers are identical.

This comes at a time when Centrelink can’t even grant pensions on time for some people, even when they lodge 13 weeks early as stipulated, or at least as strongly advised. This is clearly a combination of excessive complexity, in terms of qualifying conditions and rate calculations, combined with inadequate staff, training and technical calculating power to get this job (new pension grants) done.

But the LNP don’t know how to fix things, only how to wreck things further. Of course, they are ideologically prevented from applying the necessary fixes. The necessary fixes are to increase Centrelink staff numbers, increase training and decrease pension and benefit qualification complexity. In the context of reducing unemployment and underemployment (still a whopping 5% and 10% respectively at least), an increase in the size of the public service would be beneficial – more jobs and better provision of public services; a win-win.

Where does the money come from? Well, the real question is where do the real resources come from? We have plenty of idle human and other resources. But since neoliberal brain-washed thinkers are obsessed with money and reify it so much that they believe money (a nominal value not a real value) is actually a real limiting factor then we have to say where the money is coming from. (See Note 1.) It can come from taxing the rich more and closing off all tax avoidance and economy-distorting tax minimisation lurks. It can also come from increasing deficit spending. A mix the two sets of measures would be best.

This is very easy to contemplate and implement if you are not wearing neoliberal eyewash blinkers or if you are not a neo-liberal Machiavellian deliberately skewing the economy with economy distorting subsidies for the rich (yourself) with negative gearing, low capital gains taxes, diesel fuel subsidies for miners etc. etc.

I hope the public wakes up soon. Australian can’t take much more of the economic, social and environmental damage of neoliberalism. On the environmental damage issue, National Geographic notes “Half of the Great Barrier Reef has been bleached to death since 2016.” That is a very stark and emblematic fact. Australia needs to set an example by rapidly phasing out all thermal coal mining and burning. (Sorry, I couldn’t avoid an environmental example.)

Note 1. There is a real issue of currency stability but the dangers of inflation in a low wages, low interest rate era are much exaggerated. This continued monetary fixation on inflation fighting to the exclusion of all other goals (like full employment for all who want it) is a clear case of (economic) generals fighting the last war (1970s stagflation) instead of the current war (near deflation, near recession, infrastructure lag, un- and under-employment, along with stagnant wages.

Conclusion

We have to get rid of the sclerotic LNP and hope a new government can think more clearly outside the neoliberal/monetarist paradigm.

@ Jerry Brown

Thanks for your thoughts. Indeed, I’m writing from Germany but was referring to the US.

I think I didn’t make myself clear. In no way I’m condoning actions like TARP and HARP and have spent the last 9 years debating european Obama-lovers how he didn’t “save the economy” and why the only thing he got (marginally) right was the stimulus program instead of engaging in stupid EUROnomics, i.e. austerity. However, those programs were proof of the power of the government to spend an incur mass deficits, without “tanking” the economy because of the rise in sovereign debt. It was how it was performed and whom it benefited that I dislike.

I understand the point of the banks being system relevant, but there is just no incentive for the government or anyone who is not a stakeholder to guarantee the full payout, is there? It’s one thing to save a bank for their reckless lending and another thing to reward that behavior. How is any of that “fair”? The sole justification for one to pay interests on a loan is to compensate the lender for the risk of default. If this risk is eliminated through government action, why pay interests?

As I noted, the banks already are selling debt, e.g. student loans, at a discount rate to private entities that subsequently try to get as much of the nominal value back. Quite often in nefarious ways and involving borderline harassment of the debtors. I think it was the comedian John Oliver who put up a company and bought about a million bucks in student loan debt for only a couple of hundred thousend dollars and subsequently wrote it off. that is a load of debt that simply vanished into thin air. So again, why shouldn’t the federal government scale such a program up? The banks are already seeking to offload those loans on either suckers or the previously mentioned loan sharks. If I’m right, it’s an opportunity to exchange a bunch of household debt for just a fraction of public debt. So the banks are being relieved of toxic assets, I don’t like rewarding that, but more importantly, a bunch of regular people is freed from an otherwise inescapable situation. Banks making smaller losses or even moderate gains where they should have lost a lot of money is a price I would be willing to pay.

“And actually, the federal government did some of both (up to $29 trillion’s worth according to Randy Wray) during the financial crisis through Federal Reserve actions and the TARP and Harp programs.”

This is not what I’m talking about, because the TARP and Harp programs bailed out the lenders (and corporations) not the debtors. Leaving aside the Gov. buying shares of corporations and concentrating for now on the banks, I understood the whole shady business tho have gone something like this:

Debtor: “Dear bank, I’m broke and am therefore defaulting on my mortgage.”

Bank: “That sucks because we really need you not to default or our house of cards falls apart. Hey, useless government, save me OR ELSE!”

Gov: “I’m soveraign of a fiat, floating currency in the richest country of the world. I could provide the necessary funds to ensure the most important banks stay in business and are able to provide system relevant services and at the same time enable the debtors a fresh start through debt relief. I’m not , however, obligated to pay out in full the nominal value of those bad deals, nor must I consider the interests of any stakeholders from the “rescued” banks. But since I’m thoroughly infiltrated by neoliberal hacks who worked or will work for one of those banks and whose close friends and relatives work or are stakholders in them, I’ll do it anyway and to hell wit the “little people”.

Bank: “We’ll take that, but do try to interfere less with our business next time. This was still somehow all your fault and we still wish we could drown you in a bathtub.”

Debtor: “I’m in just as bad a position as I was before all this started.”

And what I was expecting from the government would have been:

Gov to the banks: “Tough luck, son. Such are the ways of the “free market”. You get greedy and make bad loans, you go belly up. However, since in the past we made the stupid mistake of conflating investment and commercial banking, I can’t entirely let you go broke. I will provide the necessary funding to ensure you remain operational but not a penny more than that. I will do so, by buying your bad assets, at say 40% of face value, and pass the savings on to the original debtors.

Bank: “We’ll take that, but do try to interfere less with our business next time. This was still somehow all your fault and we still wish we could drown you in a bathtub.”

Debtors: “Wow, I didn’t know a government actually did stuff for it’s people. Maybe those libertarians, deficit hawks (and doves) and “drown-the-gubmint-in-a-bathtub” conservatives are wrong after all. It might sound silly, but maybe we should RECLAIM THE STATE.

Due to the time zone difference, I’m not sure you’ll read my reply, but I would be interested on your take. Best regards!

It probably would have been better if the government had handled it more like your second scenario instead of the way they did do it.