In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

ECB continues to play a political role making a mockery of its ‘independence’

Those who follow European politics will be familiar now with the recent events in Italy. I wrote about them in this blog post – The assault on democracy in Italy. The facts are obvious. The democratic process for all its warts rejected the mainstream political parties in the recent national election and minority parties Lega Nord and M5S formed a governing coalition. The trouble started when they nominated Paolo Savona as Finance Minister. He had occasionally made statements that paranoid European elitists would interpret as being anti-Europe and anti-German. The political solution was easy and Italian President Sergio Mattarella vetoed Savona’s nomination. The Coalition withdrew and a right-wing technocrat Carlo “Mr Scissors” Cottarelli was to be installed as Prime Minister. That arrangement didn’t last long and the Lega Nord/M5S coalition emerged in government with the unelected Guiseppe Conti the new Prime Minister. But the interesting story to emerge out of all that relates to overt political behaviour by the supposedly independent European Central Bank. It has been clear for some time that the ECB has used its currency-issuing capacity to ensure that ‘spreads’ on Member State government bonds (against the benchmark German bund) do not widen too much. But it is also clear that when the ‘market forces’ do increase the spreads, which foments a sense of financial crisis, the ECB doesn’t necessarily act immediately. A good dose of crisis talk is what the political process needs to keep the anti-European forces at bay. The ECBs behaviour in this context became very political in the recent weeks and the only explanation is that they wanted the sniff of crisis to pervade while all the negotiations were going on over who would emerge as the new government in Italy. Democracy suffers another blow in that neoliberal madhouse that is the European Union.

As background to this topic the following blog posts (among others) are relevant:

1. A central bank can always prevent government default (June 23, 2015).

2. ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme – more smoke and mirrors (May 30, 2016).

3. ECB is running out of debt to buy – more smoke and mirrors needed (September 7, 2017).

At the outset, there are two issues:

1. While offensive to many conservatives, it is obvious that any central bank can control yields on government debt instruments at any maturity and at any level (including zero) if it chooses.

The ECB has demonstrated that through its Securities Markets Program (SMP), launched on May 14, 2010 and then, its successor, the Expanded Asset Purchase Programme, and more specifically, the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP).

So there is no reason for damaging bond market spreads to occur within Europe. Rising bond spreads in the Eurozone situation signal financial distress for specific Member States and a falling level of confidence in the solvency of the specific government facing rising yields.

In turn, they generate political stress and we have seen how conservative pro-Brussels elements have manipulated the spreads to advance pro-European narratives at the expense of any contrary sentiments, which may including exit-type pressures.

2. Under what terms does the central bank actually remit this capacity?

Given that the ECB can control all the spreads if it chooses, questions have to be asked when they rise, especially if those divergences are occurring at important turning points in domestic political events – such as we saw in Italy over the last month.

The question always has to be asked – why would the ECB not immediately choke off the rising spreads? We know they allow the spreads to widen for a time and then eventually eliminate them (mostly).

The obvious answer, which I have come to in previous episodes (for example, 2011-2012) was that the ECB plays its part in bringing Eurozone Member States to heel.

They sometimes do this crudely – for example in June 2015 – when they effectively threatened to bankrupt the Greek financial system unless the Syriza agreed to the pernicious bailout terms imposed on them by the Troika (of which the ECB was an active partner).

That was as blatant an act of democratic sabotage from the supposedly independent central bank as you would ever witness.

But they can also interfere politically in more subtle ways and some forensic analysis is required to sort out the bland central-bank speak ‘motherhood’ type statements the ECB issues from time to time and the underlying reality.

While the ECB claims it operates transparently, it should be forced to release internal communications, particularly memos from management to the system operators, which issue instructions on the monthly PSPP purchases and when the proportions with respect to the ‘capital key’ are to be violated.

Central banks can control bond yields whenever they choose

Let’s dispense with the first issue.

I have read several times in the last few weeks, particularly in relation to Italy, that central banks cannot really control spreads.

That is simply not true.

In the second-listed blog post above – ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme – more smoke and mirrors (May 30, 2016) – I provided a detailed explanation of how the ECBs current Expanded Asset Purchase Programme operates.

The ECB write that:

By increasing demand for assets more broadly, this mechanism of portfolio rebalancing pushes prices up and yields down, even for assets that are not directly targeted by the APP.

One of the components of the overall APP is the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) – whereby the ECB buys up “public sector securities” in return for the creation of bank reserves.

The PSPP followed earlier ECB funding of fiscal deficits during the crisis, although the ECB always maintained in its classic central-bank-speak that it was just maintaining liquidity in the banking system.

For example, the Securities Markets Program (SMP) was launched on May 14, 2010 at the height of the crisis and opened the possibility that the ECB and the national central banks could “conduct outright interventions in the euro area public and private debt securities markets”.

This was central-bank-speak for the practice of buying government bonds in the so-called secondary bond market in exchange for euros, that the ECB could out of ‘thin air’.

Government bonds are issued to selective institutions (mostly banks) by tender in the primary bond market and then traded freely among speculators and others in the secondary bond market.

This meant that the ECB was able to control the yields on the debt because by pushing up the demand for the debt, its price rose and so the fixed interest rates attached to the debt fell as the face value increased.

Competitive tenders then would ensure any further primary issues would be at the rate the ECB deemed appropriate (that is, low).

Please read my blog – A central bank can always prevent government default (June 23, 2015) – for more discussion on this point.

I have written before that the SMP saved the euro because it allowed the ECB to fund fiscal deficits of governments that were approaching insolvency (see below).

One of the hallmarks of Monetarism and its later derivatives, including New Keynesian macroeconomics, is that the central bank has to become ‘independent’ (free from political influence) for it to be credible. Otherwise private agents will not believe that it is committed to an anti-inflationary strategy and so will bet against policy strategies.

I consider that myth in this blog posts – The sham of central bank independence (December 23, 2014) and The sham of ECB independence (October 24, 2017).

However, the capacity of the central bank to control yields and eliminate the risk of government insolvency has nothing to do with so-called ‘credibility’ among private bond investors.

Whether the private bond markets believe that the central bank has that capacity is irrelevant. They soon see it in the trading realities of the secondary bond markets when they keep getting outbid for bonds by the central bank that always has a superior purchasing capacity.

They see it when yields that they would like to rise (to reflect risk or greed) stay low because the central bank demonstrates its unflinching commitment to control rates – as it only can in a modern monetary system.

So belief soon adjusts to reality. Remember that in a fiat currency system with no convertibility (into gold etc) and no fixed exchange rate arrangements in place, it is the currency issuer that is in ‘charge’ not the bond market dealers.

The latter are supplicants at best, beggars who want their dose of corporate welfare. They have no power against the currency issuer if the latter chooses to exert that power.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

The outgoing Vice President of the ECB, Vítor Constâncio told the Italian press (May 30, 2018) – Si allentano le tensioni sullo Spread. Constancio esclude ipotesi scudo BCE:

L’ipotesi di attivare il meccanismo di scudo anti-spread della BCE sull’Italia richiederebbe l’accettazione, da parte dell’Italia, di un programma di aggiustamento dei conti pubblici.

Which translates to Constâncio admitting that the ECB has the capacity to provide so-called ‘anti-spread protection’ to the Member States.

He also added the bullying element (the political element which transcends any Treaty obligations or roles that the ECB has) – that the only way that a nation could benefit from the ECB’s ‘anti-spread’ protection, is if it accepted the fiscal rules and submitted to the austerity bias.

So the ECB can control any bond spread they choose. However, in the Eurozone, such is the dysfunction, that the central bank becomes the blackmailer.

It hangs a Sword of Damocles over the heads of Member State governments along the lines of we will send you broke unless you comply with the Brussels austerity ideology.

This is one of the many ways that democracy has been severely compromised by the operations of the European Union and, specficially, the Economic and Monetary Union.

The Securities Market Programme (SMP)

I wrote about the SMP in detail in my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015).

Working notes appeared in this blog post – Options for Europe – Part 90 (May 23, 2014).

The Securities Market Program (SMP) ran from May 2010 to September 2010 and allowed the ECB to purchase government bonds in the secondary markets for five Eurozone Member States (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Italy).

It was replaced in September 2012 with the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program.

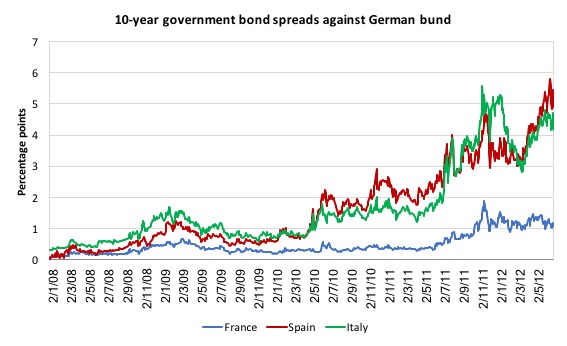

The following graph shows the 10-year government bond spreads against the German bund for France, Spain and Italy between January 2008 and June 29, 2012 (daily data).

The next graph shows the weekly purchases under the SMP for the program. There were two main purchasing periods: May 2010 and then again in August 2011 into 2012. Between March 25, 2011 and August 8, 2011 there was no SMP purchases by the ECB.

So the program was specifically active when bond spreads were rising rapidly in what the ECB considered to be ‘stressed’ Member States, signified by very weak private demand for government debt.

These nations were in danger of fairly immediate insolvency and the ECB had no choice but to intervene or else the Eurozone would have likely fallen apart.

On February 21, 2013, the ECB finally released data for “the Eurosystem’s holdings of securities acquired under the Securities Markets Programme (SMP)” (Source):

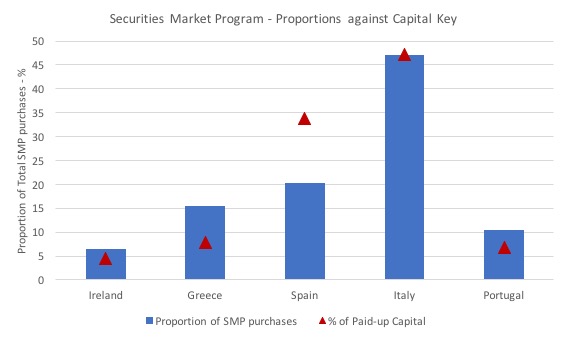

The following graph shows the total purchases of government bonds by the Member State (blue bars) and the proportion of contribution to the ECB’s Paid-up Capital by the respective Member States (red triangles).

Note that these paid-up capital proportions are not the total proportions (defined by the so-called Capital key, which includes all central bank contributions).

The ECB purchases for Italian government debt were almost exactly proportional (47.16 per cent of total SMP purchases and Italy contributed 47.19 per cent of the total paid-up capital of the five Member States.

The ECB purchased proportionally more assets from Ireland, Greece and Portugal than their contribution to the paid-up capital might suggest and much less from Spain. Greek purchases were capped as it became ‘colonised’ by a sequence of pernicious bailout programs.

The point though is that the ECB never pretended that these purchases were in any way to be proportional with the capital contributions made by the five nations.

The fact was that these nations were on the brink of insolvency and the SMP was the difference between staying afloat and sinking.

For Italy, the spread was 0.955 points on May 13, 2010. It spiked up to 1.802 points on June 7, 2010 but quickly came down again with initial ECB purchases under the SMP.

The real stress for Italy came in 2011, which coincided with the second period of very large ECB purchases of Italian (and Spanish) government debt beginning August 2011.

On April 12, 2011, the Italian-German spread was 1.207 points. It started to accelerate upwards around July 2011 and by August 4, 2011 had read 3.911 points.

It would rise again and peaked at 5.562 points on November 9, 2011. The ECB was very active in that period under its SMP.

But the ECB didn’t have to eliminate the spreads entirely. In Italy’s case, for example, I estimated that the SMP reduced the spread by around 1 to 1.5 percentage points in 2011. All it had to do was create the certainty that if the private bond investors kept participating in the primary issues they would be able to offload onto the ECB if the situation proved dire.

The other point to note is that if the ECB had have ran its SMP without the austerity conditionality being attached then the Eurozone would have recovered from the GFC fairly quickly and the spreads would have fallen anyway.

The so-called public debt crisis that overtook the Eurozone was entirely the fault of the policy makers who insisted on austerity at the expense of growth.

Recent spread activity in Eurozone bond markets

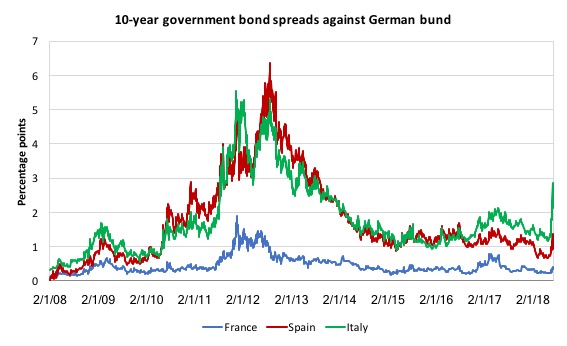

The first graph shows daily bond yield spreads (against the German bund) from the first trading day in January 2008 to June 8, 2018 for Italy, Spain and France.

I provided this graph to allow you to see the most recent events in context.

The next graph shows the spreads since February 26, 2018 to June 8, 2018. The Italian national election was held on March 4, 2018, at the end of the first trading week shown in this graph.

The bond markets were benign in the period that followed as the negotiations as to who would form the next Italian government ensued.

On the last trading day in April (30th), the Italian spread was at a low 1.218 points and had been falling over the course of 2018 to date.

By May 29, 2018, the spread peaked at 2.847 points, a substantial increase. This was two days after President Mattarella refused to appoint Savona as Finance minister in the Lega/M5S coalition government.

There was some spillover to Spanish spreads but that may have been to do with the political uncertainty in that nation. French spreads did budge.

The political role of the ECB in the Italian electoral process

So what was the ECB doing during May as the Italian spreads more than doubled?

While the political machinations in Italy were unfolding over the last month and the bond spreads were rising, the ECB was working behind the scenes, manipulating the political process via significant changes in its PSPP purchases.

It could have easily prevented the spreads from rising as much as they did (or at all) but it chose a different course of action, which is now evident in the most recent data available for its May purchases.

The Financial Times article (June 4, 2018) – ECB bond buying under scrutiny from Rome – reported that:

The ECB has come under fire from Italy’s new populist government after revealing that it scaled back the proportion of Italian sovereign bonds it bought as part of its economic stimulus programme during Rome’s political turmoil last month.

Twitter went alive with all sorts of conspiracy (against the ECB) and apologist (for the ECB) claims rife.

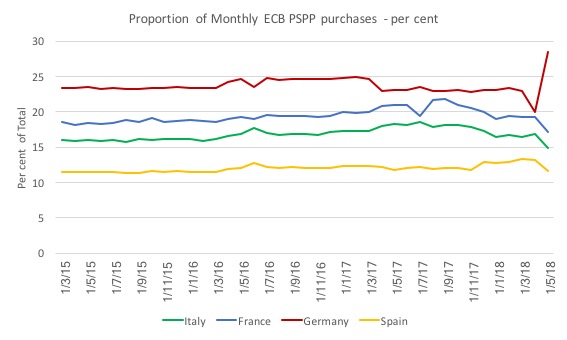

First, when the ECB issued the data for May 2018 – History of cumulative purchase breakdowns under the PSPP – and the following graph started to do the rounds (in various guises).

Clearly the May figures showed a rather bizarre increase in the share of purchases for German public debt and falls for Spain, Italy and France

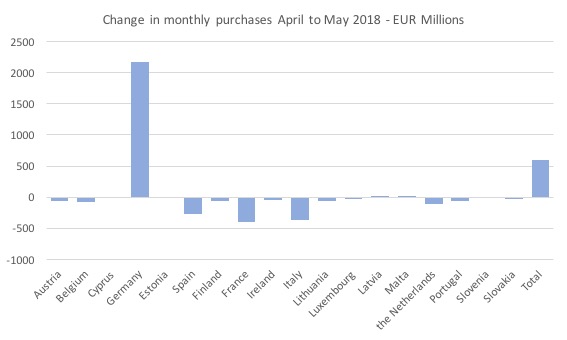

The next graph shows the absolute change (EUR millions) between April and May 2018 for all the Eurozone Member States that participate in the PSPP.

So for most Member States, the ECB purchased less debt while Germany rose sharply in absolute and relative terms. Only Germany, Latvia, and Malta were positively purchased during May 2018 by the ECB.

From January 2018, the ECB determined it would drop its monthly net purchases under the APP to €30 billion of which it intended “to allocate 90% of the total purchases to government bonds and recognised agencies”.

But since January, the monthly purchases under the PSPP have been well under the €27 billion level (January €20,905 million, February €21,801 million, March €20,774 million, April €23,631 million, and May €24,230 million).

So, immediately, the ECB had scope under its own guidelines to purchase €2,770 million more government bonds under the PSPP.

We will return to that issue.

So the facts are obvious. At a time when the Italian bond auction and yields were under stress, the ECB decreased its May 2018 purchases of Italian government debt – quite sharply.

We will consider that in more detail presently.

But first we need to put another issue to bed.

Second, on what basis does the ECB allocate its PSPP purchases across the planned €30 billion per month?

The ECB provides a – Public sector purchase programme (PSPP) – Questions & answers – page (last updated on May 25, 2018 – which is telling).

We learn that:

Q2.1.1 When the programme was announced, the ECB said that the purchases would be divided between countries on the basis of the ECB’s capital key. Will the weightings need to be applied on a monthly basis, with each NCB buying the proportionate amount each month, or do these shares refer to the programme as a whole?

The ECB’s capital key guides purchases on a monthly basis. However, this does not imply that a precise achievement of capital key shares is strictly targeted every month, as some flexibility on a monthly basis supports the smooth implementation of the programme.

The – capital key – (or capital subscription) denotes the proportions in which the Member States contribute to the capital of the ECB, which is a wholly own entity of the National Central Banks (NCPs).

The rules dictate that:

The NCBs’ shares in this capital are calculated using a key which reflects the respective country’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU. These two determinants have equal weighting.

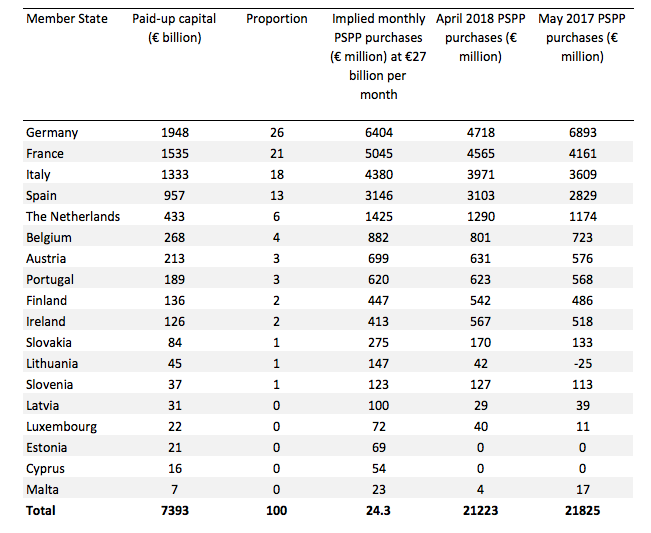

The following graphic is the latest Capital Key data (for the 19 Member States).

But with Greece barred from the PSPP the adjusted capital key implies higher proportions which are captured in the following table. I also included the April and May 2018 purchases under the PSPP. The implied PSPP purchases column under the APP rules is calculated assuming that 90 per cent of the APP purchases of €30 billion will be government bonds.

However, the complexity is that 10 per cent of those purchases can be from so-called supranational institutions, which means that on average around €24.3 billion worth of bonds from the Member States would comprise the target. The total purchases are then allocated by Member State according to the adjusted capital key.

It has been obvious since the inception of the PSPP that the ECB hasn’t followed the ‘capital key’ guideline very closely at all in allocating its monthly purchases.

The ECB provides a time series of the – Cumulative purchase breakdowns under the PSP.

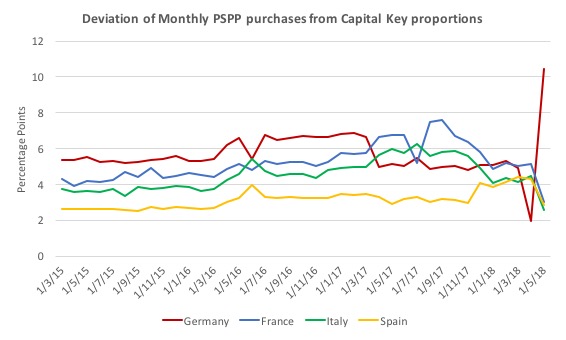

If we take Greece out of the Capital Key and recalculate proportions, we can calculate the deviation in PSPP purchases from the adjusted Capital Keys over the course of the PSPP.

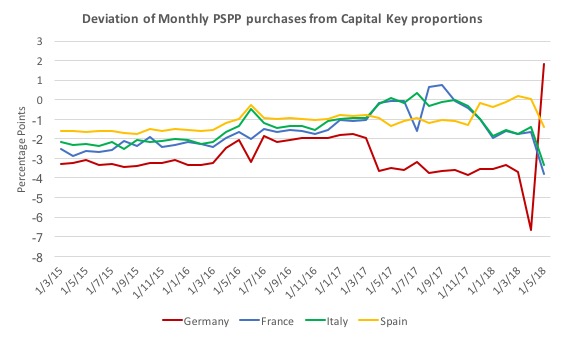

The following graph shows the deviation (in percentage points – that is comparing the monthly proportion of total purchases against the proportion of paid-up capital) since the inception of the PSPP for Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

So any claim that the May dynamics were in some way driven by a need to maintain proportionately with respect to the capital key is ludicrous.

If we base the deviation on the existing capital key which includes Greece then the following graph would be appropriate.

Either way, there is little correspondence between the monthly purchases and the strict paid-up capital proportions.

The official word from the ECB about the May dynamics was reported by Reuters (Source):

Several countries saw their share in net purchases go down in May 2018, not just Italy.

This is the result of agreed and communicated rules on the timing of re-investments during the net purchases phase.

German bond redemptions were high in April, had to be spread to May.

In absolute terms, net buying for Italy in May was higher than March and January.

On October 26, 2017, the ECB’s press release – Additional information on asset purchase programme – informed us that the Bank:

… provides additional data on redemptions as well as information about reinvestments and role of private sector purchase programmes

The ECB also tells us that:

During the period of net asset purchases, PSPP principal redemptions will be reinvested in the jurisdiction in which the maturing bond was issued.

Which means that if a heap of German bonds are about to mature, the PSPP purchases will repurchase that nation’s debt to maintain the proportions.

An examination of the – Redemption Dataset – is interesting.

The following graph shows the growing redemptions as the earlier PSPP purchases start to mature and are replaced. The blue bars are actual redemptions and the green bars are estimated redemptions in the coming months.

The point to note is that in April 2018, there was a large volume of bonds held as the ECB’s PSPP portfolio that needed to be turned over. A high proportion of those redemptions were German bunds.

Which is consistent with the ECB’s statement and goes some of the way to dismissing the May result as a “technical” matter.

With the future estimated redemptions looming large (green bars) one would expect to see more bizarre dynamics in the monthly purchases should the ECB retain form.

When the Expanded Asset Purchase Programme was announced on January 22, 2015, the ECB said they would be making purchases of €60 billion per month on average.

An ECB Economic Bulletin (Issue 7/2017) article – The recalibration of the ECB’s asset purchase programme – noted:

From March 2015 to March 2016 the Eurosystem purchased public and private sector securities at a pace of €60 billion per month. To accelerate the return of inflation rates to levels consistent with the ECB’s definition of price stability, monthly purchases were increased to €80 billion from April 2016 to March 2017. In December 2016 the Governing Council announced a recalibration of the APP, extending the net purchases until December 2017 at a reduced monthly pace of €60 billion. Following the decision made on 26 October 2017 the monthly pace will be further reduced to €30 billion from January 2018 and net purchases will be carried out until September 2018.

But note again that even with the ‘technical’ issues relating to German bund redemptions, it seems that the total monthly purchases in May 2018 were well below the €27 odd billion government bond purchase target.

In other words, the ECB had considerable room to move without stepping outside its own purchase guidelines.

The following graph shows the deviation of the monthly PSPP purchases (€ millions) from the 90 per cent target of total APP purchases adjusted for the changing total APP target.

The question is then why would the ECB not have done more to quell the financial unease surrounding Italy?

That is where the political aspect becomes relevant if not clear.

The ECB could easily have purchased more Italian government bonds without violating its own guidelines.

By allocating that deficiency to the purchase of Italian government bonds, not only would the total monthly purchases of Italian government debt have risen but the pressure on the spreads across the maturity range would have been significantly less.

In other words, the sense of crisis that the spreads invoked was in no small part driven by the ECB’s choice rather than any ‘technical’ issue.

There was a technical matter for sure.

But there was still flexibility even within the ECB’s own stated logic.

ECB defenders claim that to really address the bond market uncertainty in Italy over the last several weeks, the ECB would have to buy more of the Italian government debt than its PSPP guidelines would permit.

These purchases would allegedly have taken the ECB outside the €30 billion per month realm (especially as there is around €200 billion in outstanding Italian government debts that have to be refinanced per year).

This argument then claims that under EU rules this would invoke the sleeping Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) programme, which could see the ECB purchase unlimited volumes of Italian government debt.

They argue that the Technical features of Outright Monetary Transactions indicate that:

A necessary condition for Outright Monetary Transactions is strict and effective conditionality attached to an appropriate European Financial Stability Facility/European Stability Mechanism (EFSF/ESM) programme … The involvement of the IMF shall also be sought for the design of the country-specific conditionality and the monitoring of such a programme.

The argument then concludes that is a step that Italy would want to avoid.

And if that programme was invoked, they argue that this would trigger major political resistance from not only within Italy but from Germany and its northern neighbours who would see it as a direct bailout.

The point that this type of argument ignores is that the ECB can temper spreads without closing out the private bond investors, as was demonstrated during the earlier years of the crisis (see discussion above about SMP).

My assessment is that if they had have scaled up purchases of Italian government debt in May 2018, the uncertainty in the Italian bond markets would have been attenuated and spreads would have fallen relatively quickly.

Conclusion

In short, the recent suspicion that the ECB has allowed Italian spreads to widen in recent weeks to undermine the proposed new coalition government does not appear to be implausible.

The ECB can argue a ‘technical’ case for the May PSPP dynamics, and there is some truth in that, given the lumpy redemptions.

But the ECB has also demonstrated over the life of the PSPP to date that its ‘guidelines’ are rather flexibly interpreted and it is clear that there was considerable scope, notwithstanding the technical issues, for the ECB to quell the growing uncertainty in the Italian bond markets.

One would conjecture with a high degree of certainty that if the Italian government was firmly pro-Brussels and it encountered the level of uncertainty in the bond markets that we have witnessed in May 2018, the ECB would have quickly moved to reduce the spreads against the German bund.

While the ECB claims it operates transparently, at the very least, it should be forced to release internal communications, particularly memos from management to the system operators, outlining any instructions that were given to guide the monthly PSPP purchases for May and to detail when the proportions with respect to the ‘capital key’ are to be violated.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill….I am one who agrees with, and can relate to “Bill can write faster than most people can read”-a puzzlement, it is obvious you agree with the loss of income to the market as a result of unemployment [hereafter UE] via your “Daily microeconomic income losses from unemployment”-what concerns me is that this is treated as an irrelevant footnote in economics-rather than hammered home–as it should be–as a pernicious loss to the bottom line! Where is the index, like GDP-so that this loss to the market is front and center-clearly it is subject to the laws of math, and thus to an index-and just reporting it as the UE rate does not signal its importance in the larger microeconomic picture. My larger point is that absent this being given its importance to the bottom line in the OECD–we cling to the archaic and fraudulent belief that “the market can provide everyone with a job”-IT IS PURE BS! And in the U.S., as propaganda, alone, this belief has been our sole method of Job Creation since WWII-and to this day…..albeit it has not resulted in a UE rate below 3% since 1953! Leaving millions jobless in its wake, it has turned our inner-cities into war zones with an epidemic of gun violence!

Out of frustration I created a “law” to apply to this phenomenon-the D/UE LAW [diminished UE]-posted elsewhere-and if in my ignorance there is such an index-would appreciate being so enlightened. I am not an economist, and my purpose, here, is to learn, not be an expert-to make sense of some things that don’t add up….

Jim Green, Democrat candidate for Congress, 2000

Bio: http://www.amazon.com/James-L.-Jim-Green/e/B001KHZIMM/ref=ntt_dp_epwbk_0

Some music for Bill….

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yEu0ULY21UI&w=560&h=315%5D

Dear Bill

Suppose that the Federal Reserve were to insure that the spread between New York State bonds and the bonds of other states would never be bigger than 1%, would the United States then not become a de facto transfer union? No matter how recklessly a state would issue bonds, it would never run a significant risk of paying much higher interest rates. The same logic applies to Europe.

If you have a gambling problem and like to borrow to finance your gambling addiction, and if I guarantee that you never have to pay more than 3% interest on your loans, am I not encouraging your profligacy and in fact transferring income from me to you?

Regards. James

Dear Bill,

This line: “Per tutti quelli che “la BCE non può controllare lo spread” is meaningless, and is not in the original document.

Dear Bill,

“June 2016 – when they effectively threatened to bankrupt the Greek financial system”

Wasn’t this in 2015?

Dear James Schipper,

If you have a gambling problem and you are finally trying to leave the RSL in Rooty Hill then if someone does not guarantee that you never have to pay more than 3% interest on your loans but just locks up the door instead and chains you to the pokie machine so that you’ll never leave this place, how do you describe this situation?

Adam K, I have no idea what you just wrote means.

Dear Larry,

The Rooty Hill RSL (officially a kind of ex-servicemen club) is located in one of the poorest areas of Sydney (between Rooty Hill and Mount Druitt). The RSL is in fact a kind of poor man’s casino, the building looks like a shining cruise ship emerging from the ocean of one-storey houses. Gambling on pokies (slot machines) and betting are proven methods of extracting money from working-class people (and not only from them). I wanted to express the view that instead of blaming the debt addicts (the Italians) we should look at the forces preventing them from escaping the debt prison. Individual Italians are in fact not debt addicts, they are victims of macroeconomic forces.

“if I guarantee that you never have to pay more than 3% interest on your loans, am I not encouraging your profligacy and in fact transferring income from me to you?”

The scandalous part is not the giving. It’s when they suddenly stopped giving starting 14/5/18, in time to dispute Savona’s nomination.

Dear Adam K,

Thank you for clarifying your comment. I sometimes don’t get Aussie slang however much I like it, even though I am a fan of First Dog. I completely agree with your assessment of the Italian situation.

We have Neoliberal dirty tricks ways of making you bond!

Dear Adam K

I wasn’t implying that the Italians are debt addicts. In fact, Italy has only a small negative international investment position, about -15% of GDP. I merely wanted to make clear that if the ECB always insures that there is little spread between the bonds of countries in the Eurozone, then it does encourage fiscal irresponsibility.

You are right. Once a country is deeply in debt, a solution has to be found which does not push that country into a deep recession, as was done with Greece. We used to put debtors in jail. Fortunately, we don’t do that anymore. Likewise, deeply indebted countries shouldn’t be punished with severe austerity.

Regards. James

Issue your own currency, fund using Overt Money Finance (don’t issue government bonds), maintain a 0% interest rate policy, provide credit through a public bank with socially responsible rules (i.e loan to income ratios) Problem solved.

Very interesting analysis.

“One would conjecture with a high degree of certainty that if the Italian government was firmly pro-Brussels and it encountered the level of uncertainty in the bond markets that we have witnessed in May 2018, the ECB would have quickly moved to reduce the spreads against the German bund.”

One would conjecture correctly methinks.

Bill,

Do you make an effort to reply to most of the comments that ask a question?

.

Anyway, I am wondering just why austerity is still being forced onto poor nations in Europe.

If we grant your proof that austerity doesn’t work as it is thought to work, then why are they still doing it 10 years after the start of the 2007/2008 GFC?

1] Is it that ‘they’ don’t grant your proof?

2] Is it that poor nations must be punished in some way for the free handout? [But, shouldn’t the punishment fall more on those responsible for the bad ratio of debt/GDP*?]

3] Is it that someone wants to drive down consumption in Europe to reduce its total release of CO2?

4] Is it that someone wants to increase inequalities in income in the poor nations?

5] Is it that someone wants to increase the inequalities between the nations of the Union? I.e., between Germany and the PIIGS?

6] Other?

.

I was thinking of all the effects of the current austerity and those are the effects that I came up with.

.

* . I thought the West had rejected the idea of collective guilt. That is, punishing a pretty big group because some small part of it was guilty with the rest not being at all guilty. The big exception is ‘war’. In war we now bomb/fire-at the whole nation and not just the armed forces like they did 250 years ago.

Hi Jim Green,

I like your idea. But, is it an index or is it a mounting total (like the national debt)?

Each year you get a total of lost income and therefore lost spending, and therefore lost sales by corps.

This can/should be added to the previous total, just like the final deficit is added to the previous total national debt to get the new total.

IIUYC, why reset the index back to zero each year?

Steve