These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

ECB’s expanded asset purchase programme – more smoke and mirrors

On January 25, 2015, the press release heading read – ECB announces expanded asset purchase programme. The ECB had decided to ramp up its quantitative easing (QE) program by adding “the purchase of sovereign bonds to its existing private sector asset purchase programmes in order to address the risks of a too prolonged period of low inflation”. We now have sufficient data to assess what has been going on under this program, and specifically under the public sector purchase programme (PSPP) components (one of three parts to the overall policy initiative). The conclusion is that the scheme has had very little impact on growth and inflation – which is no surprise. However, the pattern of purchases makes it clear that the ECB and the relevant National Central Banks (NCBs) have been engaged in a fiscal operation which has provided extensive debt relief to all Member States other than Greece. This is a demonstration of the European institutions once again engaging in smoke and mirrors (pretending to be operating within the ambit of the Treaties but openly doing the opposite) and behaving belligerently towards one nation (Greece) to ensure it stays subjugated.

The formal decision by the ECB was published – Decision (EU) 2015/774 of the ECB of 4 March 2015 on a secondary markets public sector asset purchase programme (ECB/2015/10), OJ L 121, 14.5.2015, p. 20. – on March 4, 2015, just prior to the purchasing program beginning (on April 2, 2015).

At the outset, the purchases totalled €60 billion per month. That level continued until March 2016.

On March 10, 2016, the ECB announced that it would increase the monthly purchases to €80 billion until at least March 2017 or:

… until the Governing Council sees a sustained adjustment in the path of inflation that is consistent with its aim of achieving inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

It also broadened the eligible assets to include “euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area”.

The stated aim of the Expanded asset purchase programme was to:

1. To “bring inflation back to levels in line with the ECB’s objective … closer to 2%”.

2. To help “businesses across Europe to enjoy better access to credit, boost investment, create jobs and thus support overall economic growth”.

Both aims are based on the ECBs claim that:

Asset purchase provide monetary stimulus to the economy in a context where key ECB interest rates are at their lower bound. They further ease monetary and financial conditions, making access to finance cheaper for firms and households. This tends to support investment and consumption, and ultimately contributes to a return of inflation rates towards 2%.

In this 2009 blog – Quantitative Easing 101 – I explained why these QE programs do not work to fulfill the aims specified.

In summary:

1. They just swap assets – banks get reserves and the central bank gets the bond.

2. Banks are not constrained by reserves in their lending. Giving private banks more reserves does not bring credit-worthy borrowers through their doors in search of credit.

For further detailed discussion, please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary.

Households and business firms are reluctant to borrow at present in the Eurozone because the policy uncertainty is high, policy innovation is moribund, and the state of the economy is poor.

Unemployment remains high (astronomically so in some nations) and real GDP growth is slowing (see below).

So to think that swapping some financial assets with the private sector will do much is to disclose a failure of understanding.

QE does reduce yields (interest rates) in the maturity ranges of the assets purchased which means other rates in that range will be lower. But the cost of funds is only one consideration that is taken when firms (or households) decide on whether they will increase their indebtedness.

Overwhelmingly, the poor economic outlook (and the expected uncertain returns over the foreseeable future) are stronger constraints on borrowing as the cost of funds is reduced.

Interest rates in Europe have been low for years now and still borrowing is muted.

Growth and Inflation

Is there any evidence that the huge intervention from the ECB has altered anything important (that is, its real economy targets of growth, investment and inflation)?

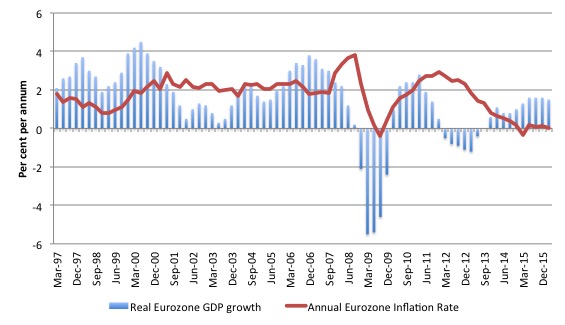

The first graph show the history of real GDP growth (annual per cent) and the inflation rate for the Eurozone 19 Member States from the March-quarter 1997 to the March-quarter 2016.

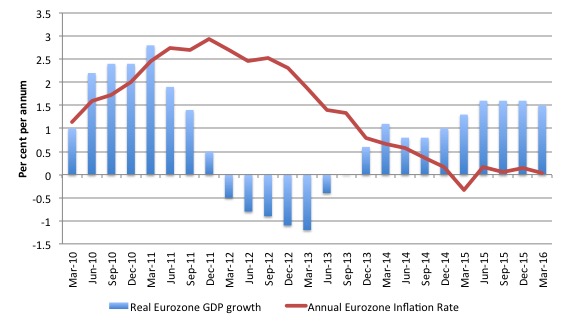

To provide more focus, the next graph is a sub-sample of the previous graph starting at the March-quarter 2010. The expanded asset purchasing program began after the Eurozone inflation rate went negative in early 2015.

Two points to note:

1. Real GDP growth has slowed over the last four quarters.

2. The inflation rate has more or less remained stuck at zero (or slightly negative)

The inference is not that the expanded APP has caused the slowdown in growth or the deflationary outlook, but rather that it has not changed the underlying dynamics, especially when we consider the size of the intervention.

In other words, the ECB’s aims have not been fulfilled (so far).

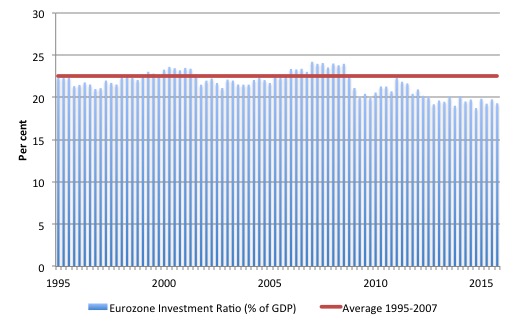

The next graph shows the investment ratio for the Eurozone 19 Member States (total capital formation as a per cent of GDP) from the March-quarter 1995 to the December-quarter 2015.

The pre-crisis average was around 22.5 per cent (red line). It has now dropped to 19.3 per cent (December-quarter 2015). When the new asset purchasing program began it was 19.9 per cent.

Conclusion: while investment spending takes time to respond to changes in the policy environment, given the planning etc that has to accompany the commitment to make actual outlays, there is no evidence that the investment climate in the Eurozone has improved in any appreciable way.

The investment ratio has fallen in the last year and remains at depressed levels.

How does the PSPP work?

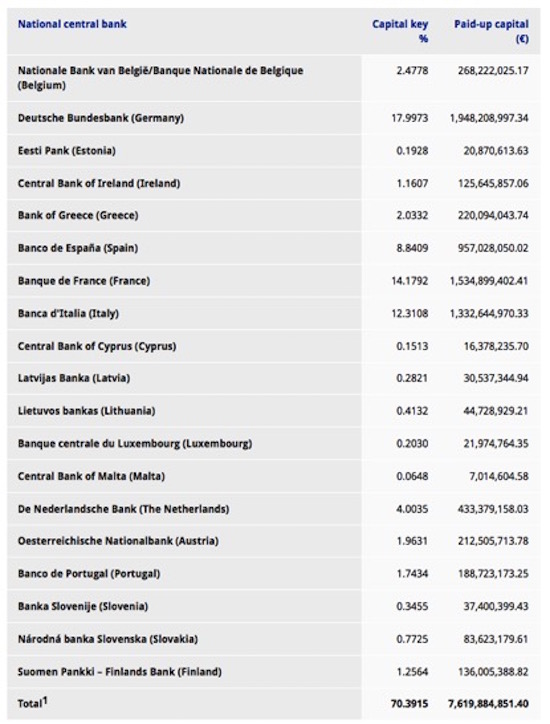

The March 4, 2015 decision to expand the asset purchasing scheme “to include a secondary markets public sector asset purchase programme” (the PSPP program), led to the National Central Banks (NCBs) in the Eurozone being able to buy up government bonds “in proportions reflecting their respective shares in the ECB’s capital key”.

The – capital key – (or capital subscription) denotes the proportions in which the Member States contribute to the capital of the ECB, which is a wholly own entity of the NCBs.

The rules dictate that:

The NCBs’ shares in this capital are calculated using a key which reflects the respective country’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU. These two determinants have equal weighting.

The following graphic is the latest data (for the 19 Member States).

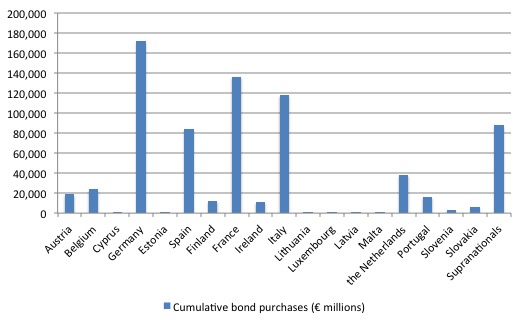

The ECB provides a time series of the – Cumulative purchase breakdowns under the PSP.

The following graph shows the cumulative purchases (€ millions) by nation since the end of March 2015 to the end of April 2016 (blue columns).

Notice that Greece is missing from this list – which was the first thing I noticed when I examined the data last week. More about which later.

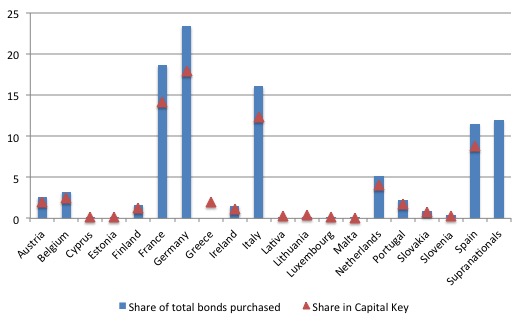

The next graph shows the share of the cumulative purchases by nation in the total (blue columns) with the red triangles denoting the nation’s percentage share of the capital key.

Remember, under Article 6 – Allocation of Portfolios – of the March 4, 2015 ECB decision:

… the NCBs’ share of the total market value of purchases of marketable debt securities eligible under PSPP shall be 92 %, and the remaining 8 % shall be purchased by the ECB. The distribution of purchases across jurisdictions shall be according to the key for subscription of the ECB’s capital as referred to in Article 29 of the Statute of the ESCB.

The other restriction under Article 5 Purchase limits is that the NCBs can only purchase up to “an aggregate limit of 33 % of an issuer’s outstanding securities”.

The question then is: How closely is the PSPP keeping to the capital key proportions?

Answer: Not very close.

We can see that in the case of France (18.6 per cent of total purchases, 14.2 per cent capital key), Germany (23.4 per cent of total purchases, 17.9 per cent capital key), Italy (16.1 per cent of total purchases, 12.3 per cent capital key), and Spain (11.5 per cent of total purchases, 8.8 per cent capital key), the relevant NCBs have been buying significantly more than indicated by the contribution to the ECB capital.

The discrepancies for other Member States (bar Greece) are very small.

The PSPP is largely rendered operational at the NCB level. The decision of March 4, 2015 said that the NCB share of total purchase would be around 92 per cent.

Many wonder how these large-scale purchases of public bonds (debt) which has been used to raise euros to cover public deficits in the Member States is legal under the Treaties, which prohibit such action.

Remember that under Article 21 – Operations with public entities – of the Protocol on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank – which is an annex of the Treaty establishing the European Community we know that:

In accordance with Article 101 of this Treaty, overdrafts or any other type of credit facility with the ECB or with the national central banks in favour of Community institutions or bodies, central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies governed by public law, or public undertakings of Member States shall be prohibited, as shall the purchase directly from them by the ECB or national central banks of debt instruments.

Although, “national central banks may act as fiscal agents” for their relevant governments. More about this later.

So is the PSPP funding government deficits?

The ECB claims that it:

… strictly adheres to the prohibition on monetary financing by not buying in the primary market. The ECB will only buy bonds after a market price has formed. This ensures that the ECB does not distort the market pricing of risk.

So it waits a few days after the primary issue by the government in question while the private bond markets sort out the price (risk assessment) and then it buy the debt.

Smoke and mirrors really!

Go back to May 14, 2010, when the ECB established its Securities Markets Program (SMP), which opened the possibility that the ECB and the national central banks could “conduct outright interventions in the euro area public and private debt securities markets” (Source).

This was central bank speak for the practice of buying government bonds in the so-called secondary bond market in exchange for euros, which the ECB could create out of ‘thin air’. Pretty much what the PSPP is!

Government bonds are issued to selective institutions (mostly banks) by tender in the primary bond market and then traded freely among speculators and others in the secondary bond market.

To understand this more fully, the SMP decision meant that private bond investors (including private banks) could offload distressed state debt onto the ECB. The action also meant that the ECB was able to control the yields on the debt because by pushing up the demand for the debt, its price rose and so the fixed interest rates attached to the debt fell as the face value increased. Competitive tenders then would ensure any further primary issues would be at the rate the ECB deemed appropriate (that is, low).

After the SMP was launched, a number of ECB’s official members gave speeches claiming that the program was necessary to maintain “a functioning monetary policy transmission mechanism by promoting the functioning of certain key government and private bond segments” (see Statement from ECB Board Member José González-Páramo, 2011).

In other words, by placing the SMP in the realm of normal weekly central bank liquidity management operations, they were trying to disabuse any notion that they were funding government deficits.

This was to quell criticisms, from the likes of the Bundesbank and others, that the program contravened Article 123 of the EU Treaty.

Whatever spin one wants to put on the SMP, it was unambiguously a fiscal bailout package. The SMP amounted to the central bank ensuring that troubled governments could continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

Whether it breached Article 123 is moot but largely irrelevant. The SMP reality was that the ECB was bailing out governments by buying their debt and eliminating the risk of insolvency. The SMP demonstrated that the ECB was caught in a bind. It repeatedly claimed that it was not responsible for resolving the crisis but at the same time, it realised that as the currency issuer, it was the only EMU institution that had the capacity to provide resolution. The SMP saved the Eurozone from breakup.

The ECB officials now try to justify the PSPP in the context of their price stability charter. It says:

The ECB implements the monetary policy of the euro area. It pursues its mandate of price stability with the instruments defined in the Treaties. Outright purchases of marketable instruments are explicitly mentioned as a monetary policy instrument (in Article 18.1 of the Statute of the ESCB). This includes the possibility to purchase instruments such as government bonds, as long as they are bought on the secondary market from investors and not on the primary market, i.e. directly from Member States.

But an astute mind will see the smoke and mirrors are alive and well.

Now consider the implications of the relationship between the NCBs and their Member States.

More smoke and mirrors – the hidden debt relief

Remember the NCBs are creatures of each Member State – they are part of the government machinery in each state. They can receive interest payments from the relevant Ministry of Finance for government debt they might hold from that Member State but at the end of each accounting period the accounting is reversed.

It is a case of the government lending to itself!

The New York Times article (March 9, 2015) – Quiet Start to Central Bank Bond-Buying Program for the Eurozone – commented on the ECB announcement that it was expanding the asset purchasing program by saying:

The eurosystem refers to the network of eurozone national central banks, which are doing most of the purchasing on bond markets. Typically they are buying the bonds from large banks that act as dealers …

But one side effect of the program could be to relieve pressure on government budgets. Most of the purchases are being conducted by national central banks, which will buy their own governments’ bonds and collect interest payments and other profits.

Later, the central banks will pass the profits back to their national governments. That means the debt effectively becomes free of cost to the issuing country.

Recall, that so far the ECB has bought no Greek government debt under the PSPP. Mario Draghi was asked whether the PSPP would apply to Greece in the question time at a Press Conference he held in Frankfurt on January 22, 2015.

In the transcript – Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A) – we read:

Question: My first question would be, it’s not actually very explicit here in the press release whether that means that you’re not going to buy into Greece’s debt right now …

[Draghi answered] … let me say one thing here. We don’t have any special rule for Greece. We have basically rules that apply to everybody. There are obviously some conditions before we can buy Greek bonds. As you know, there is a waiver that has to remain in place, has to be a program. And then there is this 33% issuer limit, which means that, if all the other conditions are in place, we could buy bonds in, I believe, July, because by then there will be some large redemptions of SMP bonds and therefore we would be within the limit.

Well, it turns out that NCBs nor the ECB have bought any Greek government debt under the program – it is the only Member State so far ‘excluded’ from the purchases.

What are the implications of that?

Consider the operational meaning of what is going on. Take Germany as an example. Its NCB (the Bundesbank) has been buying up German government debt in the seconday markets at a considerable rate.

So far total purchase of German government debt amount to € 171,808 million as at April 30, 2016. The vast majority of this debt has been purchased by the Bundesbank under the PSP program.

What does that mean? Effectively, when the Bundesbank buys the German government debt it takes it out of circulation. The German government effectively pays no interest on the debt (as it would if the instruments were still held by the private entities that bought the debt on primary issue or in the secondary markets.

Moreover, when the debt held by each NCB matures, the bank will just replace it – again effectively taking the debt out of the picture.

So this scheme unambiguously provides debt relief to the Member States involved – all 18 of them – with Greece being deliberately excluded despite Draghi saying there is “no special rule for Greece”.

Draghi did, however tell the ECB governing council in September 2015 that Greek government bonds were not eligible for the QE program because the nation had not met certain conditions (re: quality).

This is in relation to the on-going nonsense surrounding the third bailout, the fact that a satisfactory Debt Sustainability Analysis had not been completed and other issues relating to that nation.

In other words, while the ECB and the NCBs in all nations other than Greece are effectively rendering a large swag of the public debt – interest free and, more or less, permanently out of circulation – they are not prepared to allow the Greek central bank to participate.

The irony is that the exclusion is because it judges the Greek government debt to be outside of its quality guidelines and not worth providing relief to, whereas the relief it is giving all the other Member States is for debt it judges to be within acceptable risk limits.

Conclusion

This is crazy logic unless we understand that the aim of all policy in the Eurozone at present in relation to Greece is to bring it to heel and keep it in a subjugated state.

The elites cannot afford to give any leeway to Greece in case it actually shows some growth as austerity is eased.

Better keep it mired in a permanent state of Depression to prove who runs the show!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“So it waits a few days after the primary issue by the government in question while the private bond markets sort out the price (risk assessment) and then it buy the debt.”

Why does this process always remind me of religious leaders refusing to touch things that are ‘impure’ in their belief structure?

Neil, because the two are currently virtually indistinguishable?

Bill what I think the goal is to force a right wing neo-liberal conservative government to get elected then the buying will happen and wow Greece will magically and secretly ecover via “austerity” (and bond buying) by conservative governing in the eyes of the Greeks and Europe. This I think is the goal of the IMF via the USA as they’re still scared of communism and socialism and see it ass their greatest threat. Poor Greeks and poor Europeans…. so sad.

Bill, just one comment regarding the proportionality of asset purchases under PSPP:

You’re quoting Article 6 Allocation of Portfolios of the March 4, 2015 ECB decision and referring to capital key data from the ECB website. Maybe you’ve noticed, that the percentage points for capital key (first column) add up to just 70,39 % – not to 100 %. Besides the ECB, there are only the NBCs of the euro area countries participating in the PSPP. Since only euro area NCBs have to pay up their capital share in full, you’ll need to calculate the share of fully paid-up capital instead. For instance, the adjusted share for the Bundesbank (1.948.208.997 / 7.619.884.851) is 25,56 %. Now take into account that the share for PSPP purchases by the NCB is 92 %, you’ll get an actual share for the Bundesbank of 23,52 %. Pretty close to the real numbers, isn’t it?

In short, smoke and mirrors, indeed!

Bill, from what source have the national central banks obtained the euro necessary to repurchase the debt issued by their corresponding treasury? Have the NCBs the authority to create euro, or is the ECB issuing euro to the NCB?

Thanks,

Joel