It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

The British NHS debate – TINA but only if you believe in nonsense

The German propagandist Joseph Goebbels would have loved the so-called ‘NHS Funding Tool’ that the London-based Institute of Fiscal Studies has wasted hours of labour producing and making available on the Internet. In fact, history would show that the German menace was probably more circumspect in his propaganda activities that the IFS, which has set about to deliberately distort the public debate in the UK over NHS funding. Its latest entry (May 24, 2018) – Securing the future: funding health and social care to the 2030s – is nothing short of a disgraceful grab for headlines. The problem is that reports such as this then feed into an uncritical press, which then furthers the fictional world that my profession has created to hide their ideological preferences against public intervention – in this case, public health systems. The IFS Report is a typical case of neoliberal analysis, which contains hidden constraints that are designed to lead towards the TINA conclusion. Britain can afford to have a first-class NHS if it chooses and the real resources are available and people desire for them to be used in that sector rather than elsewhere. My bet is that the country would be much better off if there were less bankers and investment speculators (the occupations that the neoliberals revere) and more resources in the health sector. At present, constructing the NHS challenges, which are real and growing, as a tax rise or bust type scenario is dishonest in the extreme.

None of the press reports I read on the IFS release asked critical questions – such as why there was “no more room” to increase health funding as the British population becomes older.

They didn’t challenge the IFS Director when he appeared on British radio promoting the release and said that the middle class would bear the brunt of the take hikes because taxing the wealthy would not raise enough.

The press were predictable with the headlines they decided to use.

The Telegraph (May 24, 2018) wrote – Historic tax rises on middle class families needed to save the NHS, IFS says.

The UK Guardian (May 24, 2018) wrote – NHS needs £2,000 in tax from every household to stay afloat – report – as if it was a done deal.

Its sub-headline was “Higher taxation is only way to address demands on buckling health service”.

And it ran the TINA line “there can be no alternative to higher taxation if there are to be even modest improvements to care over the next 15 years”.

Whenever you read a TINA-type statement the search for ideological bias begins immediately.

It doesn’t take long in this case to locate that bias – the fictional world of neoliberal macroeconomics and its dislike for fiscal deficits that promote well-being.

And the next day, the ‘fictional world’ had worked its way into the polity.

The British Labour MP for Birkenhead wrote in the UK Guardian (May 25, 2018) – Better ways to fund the NHS – that:

Nobody now disputes the need for a significant and sustained increase in revenue for the NHS and social care … Rather, there are two political battles to be settled: how significant an increase the country feels it can afford, and from whom it wishes the additional revenue to be raised.

The answers to these questions are obvious.

Question 1: It can afford to have a first-class NHS if there are real resources available to be allocated to that service and the people want them to be so allocated.

Question 2: The British government has unlimited financial capacity to ensure those real resources are allocated to the NHS should that be what the British people desire.

What was also disappointing was the response of the peak trade union body (May 24, 2018) – More funding isn’t just good for the NHS – it’s good for the economy – which opined that:

… household incomes will rise by 17 per cent over the 15-year period. If taxes were to rise by 2 or 3 per cent of GDP over that time, this may dent income growth but it would still be economically feasible.

Why even give the TINA argument any oxygen?

The problem is that all these players (media, unions, ‘think tanks’) are all trapped in the neoliberal narrative and cannot think outside the box.

If I was a journalist and I was interviewing the IFS on the release of their report I would have asked them to document exactly how ‘taxpayer funds’ are being used to provide financial resources to the NHS, rather than just repeat what the IFS wrote.

The IFS accompanied the release of its NHS Report with the release of what it calls the IFS ‘Funding the NHS’ Tool replete with social media capacity to ‘spread the message’ – that is, spread the deception.

The IFS ‘Funding the NHS’ Tool, for a start doesn’t allow the user to increase spending in any area – for example, areas that might help improve the health of British people and therefore take the strain of the resource-starved NHS.

So it assumes that total government spending is constant as is the fiscal balance. It assumes real GDP is constant.

So it comes down to a ridiculous exercise in cutting spending or increasing taxes and users are brainwashed with such statements as “increase taxes to pay for the NHS”.

A zero sum.

As a ‘tool’ to advance economic literacy it is a disgrace. There is no causal context (spending multipliers, cyclical sensitivities, etc).

This Institute should be defunded as it is a crude propaganda machine for erroneous neoliberal economics.

Just for the record, I cut Net EU Contribution by 100 per cent, Enterprise and Economic Development by 100 per cent and defence by 51 per cent and filled their stupid spending gap.

I would have also caused a dramatic recession and items of expenditure such as Pensioner Benefits, Public Order and Safety, Housing and Community Amenities, Employment Policies would have soared and the overall tax withdrawal would have collapsed.

Idiocy all round.

The IFS claims it “was launched with the principal aim of better informing public debate on economics in order to promote the development of effective fiscal policy.”

It should close its doors because since it was established in 1969 it has confused the public debate with its mainstream economics nonsense.

While claiming to be an “independent research institute” its publications reflect the ideological thrust of mainstream macroeconomics and the failure of that body of work to come to terms with the options available to a currency-issuing government such as Britain.

The IFS Report was co-authored by the Health Foundation.

Its main conclusions were:

1. In relation to the NHS “concerns about the adequacy of funding are once again hitting the headlines, as the health and social care systems struggle to cope with growing demand.”

2. The British “population is getting bigger and older, and expectations are rising along with the costs of meeting them”.

3. “UK spending on healthcare will have to rise by an average 3.3% a year over the next 15 years just to maintain NHS provision at current levels, and by at least 4% a year if services are to be improved. Social care funding will need to increase by 3.9% a year to meet the needs of an ageing population and an increasing number of younger adults living with disabilities.”

And presumably, spending on primary education will decline among other age-cohort sensitive outlays. That fact is not mentioned.

4. “Public spending on health in the UK in 2016-17 was £149.2 billion (2018-19 prices). That’s more than 7% of national income.”

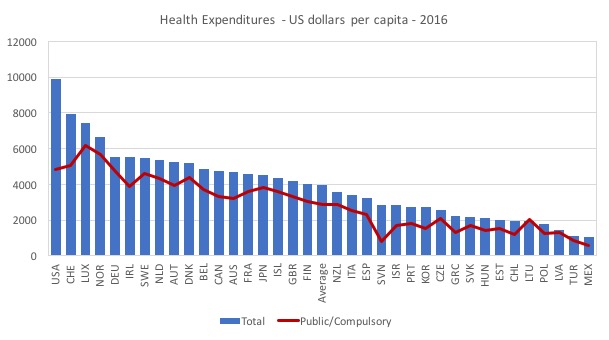

The OECD health statistics shows that Britain (GBR) is around the average for total health spending per capita (standardised in US dollars).

The following graph shows the data for 2016.

It confirms the statement made by the British public sector union, UNISON that (Source):

We pay considerably less for our NHS than most other European countries do for their health services.

The 2017 International survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund – Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Health Care – studied and compared 72 indicators across five health care domains: “Care Process, Access, Administrative Efficiency, Equity, and Health Care Outcomes”.

They drew on a variety of data – OECD, Who, European Observatory and assembled “performance scores” for ten nations (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and USA).

The results were:

The top-ranked countries overall were the U.K., Australia, and the Netherlands.

The Commonwealth Fund found that:

Current health expenditure in the UK was 9.75 per cent of GDP in 2016. This compares to 17.21 per cent in the USA, 11.27 per cent in Germany, 10.98 per cent in France, 10.50 per cent in the Netherlands, 10.37 per cent in Denmark, 10.34 per cent in Canada, 8.98 per cent in Spain and 8.94 per cent in Italy.

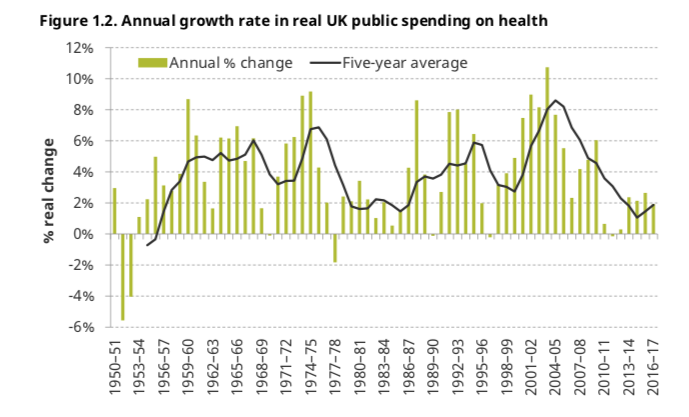

The IFS Report acknowledges that Britain is not an outlier when it comes to increasing growth in health spending.

When I considered the claim that total spending will rise by around 4 per cent per year over the next 15 years it becomes obvious that this was the norm from the 1950s onwards until the current austerity push began with the first Osborne fiscal statement in June 2010.

The following graph (reproduced from Figure 1.2 in the IFS Report) shows the annual growth in real UK public spending on health since the 1950s.

“Over the entire period, it increased by an annual average of 3.7%.”

The Thatcher and Major Tory governments (1978-79 to 1996-97) averaged 3.3 per cent.

The Coalition government (Cameron) government (2009-10 to 2014-15) averaged 1.1 per cent, while the current Tory government has averaged 2.3 per cent.

So a return to a 4 per cent average growth is hardly abnormal for Britain.

None of the analysis presented by the IFS Report about NHS funding requirements – recurrent, capital etc – are particularly contentious.

The reality is that the NHS has been starved of funds since 2010 in a period where the demand for health care services is rising as the population ages and costs rise.

Where the contention arises in when we turn to the “Paying for it” analysis.

The IFS show that:

… overall public spending as a fraction of national income is a bit lower today than it was in the late 1970s (39% of GDP today against 41.5% of GDP in 1978-79), despite the fact that health spending rose from 4% of national income to well over 7% over the same period.

They say this is indicative that “we have effectively paid for increased government spending on health by cutting spending on other things”.

But the two points don’t follow necessarily.

The share of public spending in GDP might have fallen a little but GDP has expanded several times.

But that doesn’t mean that total spending has fallen overall nor that the absolute level of individual areas of spending have fallen.

The British government certainly spends less of its total outlays on Defence and more on Health since the mid-1980s.

The IFS claim that this “similar trick” is exhausted – “There is barely any defence or housing budget left to cut”.

Then it makes its ideological leap:

While increased borrowing could fund rising health spending over the short term, sustained increases in health and care spending will require increased revenues from somewhere …

The implication is clear: in the medium term, if we want even to maintain health and social care provision at current levels, taxes will have to rise.

It then goes through a torturous analysis of which taxes should be increased.

But underlying this analysis is the erroneous belief that taxes fund government spending.

Please read my blog post – Taxpayers do not fund anything (April 19, 2010) – for more discussion on this point.

A process based on a better understanding of the currency

The TINA mantra from the IFS is meagre ideology. It sets up underlying constraints without question and by assumption reaches its conclusion – taxes must rise.

But if we break out of that artificial world then a wholly different analytical process must be followed.

First, is the fiscal deficit at an appropriate level relative to the other balances in the economy?

The following graph shows the annual sectoral balances for the UK from 1948 to 2017.

The UK is currently running a Current Account deficit of around 4 per cent of GDP and the fiscal balance is close to zero. That means that the private domestic sector is running a deficit around the same size as the external deficit.

The swing back into private domestic deficit after the recovery from the GFC began is noticeable. It means that the private domestic sector is now accumulating more debt from a relatively high base and the situation is not sustainable as a growth strategy in the long run.

With GDP growth slowing quite substantially as the fiscal drag starts to bite and with inflation falling to a yearly low in the latest data released from the Office of National Statistics, one can conclude that the fiscal deficit is now too low.

So there is scope for a widening deficit.

That option is ruled out by the IFS without discussion. They just impose a fiscally neutral assumption and then claim there can be no further spending compositional shifts – which leads logically to their claim that taxes must rise to increase government spending.

But the important debate should be around whether the current fiscal position is too contractionary. My assessment is that given the external situation and the private domestic sector saving intentions, the fiscal drag from the near balanced position is killing growth.

Second, once one opens up the analytical frontier in this way then further questions arise.

1. Is the economy at full capacity? With inflation low and falling, real wages flat and real GDP growth stagnant, my assessment is that the UK economy is some way from being at full capacity.

Why does this matter?

Simply because if the economy was at full capacity then the only way the Government could increase its use of real resources in the economy would be to deprive the non-government sector of those real resources.

That deprivation would be engineered through tax increases.

If there is some slack, then the NHS can be expanded to meet the proposed higher growth rate in health spending, simply by increasing government spending.

2. Is that the best way to fill the non-government spending gap?

The political issue that has to be determined is whether expanding the NHS in this way is the best use of extra government spending (and the non-government real resources that it would bring into productive use within the health system)?

That is not a question I can solve logically.

It is clear the NHS is among the world’s best health care systems and delivers massive benefits to the British population. But its capacity has been severely eroded by the Tory austerity.

So the case has to be made to increase spending growth to meet the future needs. That case should not be conflated or blurred by erroneous discussions of what the British government can afford.

As the currency-issuer it can buy whatever is for sale in British pounds and there is a case in my view to increase the net public spending.

I would guess huge benefits (returns) would arise from restoring the capacity of the NHS that has been eroded by austerity.

3. What monetary operations should accompany that increases in net public spending?

Given its currency-sovereignty, there is no reason for the British government to issue any further debt to match the larger deficit.

The Bank of England can manage any liquidity issues (increasing bank reserves) by simply providing a support rate on the excess overnight reserves, a practice that has become common around the world since the GFC saw central bank balance sheets expand dramatically.

The two operations – issuing a formal debt instrument and paying a support rate on excess reserves – are identical in terms of flows. The political advantage is that the Government does not have to deal with claims that it cannot pay its debt liabilities back.

4. What about the longer term?

It may be that over time, the preferences for government services will change and the commitment to the health care sector (NHS) is a longer-term one.

In that context, taxation changes may be required to alter the composition of government and non-government spending to ensure the economy does not extend past full employment while maintaining the NHS in a functional state.

Any taxation increases would not be seen as ‘funding’ government sector but rather managing non-government liquidity and purchasing power.

5. The multiplier effects of increased health spending.

Governments always spend first and then drain some (maybe all or more) of that expenditure from the economy via taxes.

I have often noted that spending brings forth its own saving. Why?

Increased deficits to restore the NHS to a first-class status would stimulate economic growth, which in turn stimulates all the leakages from the expenditure stream – saving, imports and tax receipts.

Conclusion

The IFS Report is a typical case of neoliberal analysis, which contains hidden constraints that are designed to lead towards the TINA conclusion.

Britain can afford to have a first-class NHS if it chooses and the real resources are available and people desire for them to be used in that sector rather than elsewhere.

My bet is that the country would be much better off if there were less bankers and investment speculators (the occupations that the neoliberals revere) and more resources in the health sector.

At present, constructing the NHS challenges, which are real and growing, as a tax rise or bust type scenario is dishonest in the extreme.

Trade and Growth – one graph

I have noticed some ridiculous claims being made about the relationship between Current Account balances and real GDP growth in recent days following my three part series on Trade and Finance.

The three part series is available here:

1. Trade and external finance mysteries – Part 1 (May 8, 2018).

2. Trade and finance mysteries – Part 2 (May 9, 2018).

3. A surplus of trade discussions (May 23, 2018).

I haven’t really kept abreast of the Twitter storm or various blog posts but apparently Warren Mosler and I are ignorant, stupid, haven’t read relevant literature and more.

No problem.

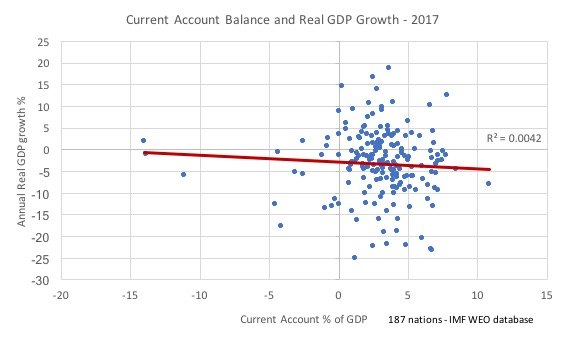

One regular reader of my blog recently asked me to present evidence that might counter the claim that nations that run current account surpluses grow more quickly than those that run external deficits.

Apparently, he had seen some correlation table on the Internet for a handful of nations which allegedly showed that such a relationship did exist. Samples of a few nations are never sound.

Well, here is a graph that shows 187 nations from the IMF WEO database (two outliers were deleted Macao and Libya because they distorted the regression plane – and made the result shown here even more compelling).

On the horizontal axis is the current account balance as a per cent of GDP in 2017 and on the vertical axis is annual real GDP growth (per cent).

The red line is a linear regression (constant and slope), which is downward sloping. Definitely not upward sloping. But the R-squared tells us that there is no relationship between the two variables.

I have also done more sophisticated regression analysis to check this result which did not negate the most simple analysis.

I would caution that bi-variate analysis of this type is not very sound and in this case conflates a number of different monetary systems – fiat, free floating; Eurozone, pegs, currency boards, etc.

In the more sophisticated work I controlled for those variations.

But my professional experience tells me that we will struggle to refute the null of no relationship no matter how complicated we get if the sample is large enough.

I also examined various years going back to 1980 (the start of the IMF WEO database) and was never able to find a positive relationship.

Anyway, I now need to go back and see if I understand what Marx meant with his opening word in the Communist Manifesto – “A”. That should keep me occupied and help improve my ignorance.

I will leave it at that.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Even if one were to go with the deceptive and misleading analysis by the egregious IFS, health resources in the UK being so apparently depleted and scarce, anyone believing this nonsense should therefore enthusiastically support the immediate abolition of the private health sector, so that all those real resources that it has commandeered be given over as a matter of urgency to the NHS, so that scarce medical care could be allocated on the basis of medical need, and not on the size of the patient’s wallet.

But no, it hasn’t been suggested at all! Funny that.

The greatest need in debate about healthcare is to bring prevention into the equation. Better diets, less pollution, lifestyles which include fresh air and excercise – these are all things which can very greatly reduce demand for healthcare. Where are the economics think tanks reporting on this?

Who is there to contradict this nonsense, Bill? Your excellent dispatch of the nonsense will only see the light of day in the community of MMT, yet it needs to be sent out to everyone. You defended the political class last Friday but I cannot agree with you except that like with quantum mechanics, progress only occurs one funeral at a time. We don’t have time.

The thing is who are the underutilised labour? It is clear that they exist from the ONS figures – both non-utilised and under-utilised. But the trouble is they are not health care professionals. Indeed, since the initiation of the Brexit process more staff have been leaving to return to their home countries than have joined. So throwing money at the NHS will not solve the problem. There simply are not the unemployed doctors and nurses out there. Worse, foreigners are actively being discouraged from coming to the UK and its “hostile environment”.

You do not talk about investment in training. That’s what is crucial so that a proportion of the unutilised labour can retrain, and new youngsters can come into the system. I would like to see some figures as to how much is being spent on education in the health care system. Not enough I would wager.

Can you tell me what is meant by TINA in this blog please?

Most of it I understand but not TINA.

Ron

There is No Alternative.

It is an initialization from the oft used phrase by neoliberals There Is No Alternative

Think tanks and management consultancies are doing a shocking amount of the shaping of the economic debate in the UK. The King’s Fund – a long established health charity turned think tank – has contributed damagingly to this. They are cheerleading both for the changes in the NHS which are leading it ever closer to a US-style system and for patient charges. A British Social Attitudes survey was carried out before these latest headlines, asking the public if they supported tax rises for this purpose. But according to The Spectator, the specific question asked was paid for by the King’s Fund, as an addition to the normal Survey. They say:

« the actual poll phrased the question in the following way: ‘If the NHS needed more money, which of the following would you be prepared to accept?’ Note the first word: ‘if’. It loads the question. For example, dear reader, if you were forced to give Mr S £1,000 would you rather pay with PayPal, Visa or cash? By answering the question, it doesn’t mean you want to give me money. But it can be spun that way. A genius ruse from the King’s Fund. »

Any serious NHS watcher will know that the real intention has been clear for a very long time – the British public are being told that more of the spending on the NHS will have to come from their own pockets in one form or another. I assume the tax argument is being proposed in this extreme way in order to soften the ground for acceptance of private co-pays and employee based state insurance schemes in its place. What Labour’s Frank Field calls creating a ‘something-for-something’ society. Although the truth about tax is that it doesn’t pay for public spending, it is also true that threatening tax rises can be used as a lever to achieve something else. Either way it lets the government off the hook for its real responsibilities and puts unfair burdens on the incomes of private citizens.

In 1945 the UK government achieved something amazing: the creation of the NHS and the Welfare State. We should collectively hang our heads in shame to see it debased on such shoddy and false arguments.

Regarding TINA I say STAB TINA – Solutions That Are Better than There Is No Alternative.

Hi Bill

Regarding your Trade and GDP growth debunking, all very well, but why bother?

I asked you in another thread context with you bothered to critique a number no-name facebook commentators and ignore SWL on the same topic (especially considering the differentai reach of these two sets of critics)? I might be labouring to draw a parallel (although now it is just two different commentators) here, but why are you bothering to answer a very obvious falsehood, when I was asking a more relevant useful question regarding Germany (and Hart reforms -> mercantilism) etc?

On the one hand, it is very obvious from the table in my previously linked Steve Keene post, that there is no correlation between GDP*/Capita* and the CAB. So, although not direct, it is unlikely that there is any relation between GDP *growth*. Then there is , of course, Greece – well it had a positive CAB in 2017, not now… with massive GDP reduction and fiscal surplus.

On the other hand, large CAB deficit countries such as the USA and UK are being fiscally deficient (as you noted today for the UK) and, surely, that would also destory any candidate correlations or maybe not?

Anyway the question remains when you comment on what Germany has done to itself though the Hartz reforms to have such a high CAB surplus (and indirectly enabling the Mark Euro exchange to be undervalued). What did the Hartz reforms do – by design or otherwise – to Germany’s labour productivity, participation rates, nominal/real wages and growth etc. There are likely to be two (or more?) baskets (e.g. labour indicators, capital flow,FDI,FPI indicators, so I guess at least 2 baskets) of parameters that can be indicative of policy and its affects?

Switzerland is very similar to Germany here but has obvious differences too – sovereign currency (but managed against the Euro somewhat), not in the SM (but a huge set of guillotine clause bi-lateral agreements). Did it have its own version of Hartz reforms? If not, what else happened to be the equivalent of the Hartz reforms, or in spite of being neighbours and having more cultural similarities compared to other surplus nations e.g. China and Japan, did Switzerland follow a quite different policy path to achieve its CAB surplus?. If the latter, what was that path?

Japan and China are two very different economies to each other and Germany/Switzerland. The chance of them each having quite different path trajectories to achieve CAB surpluses is very high, but maybe I am wrong.

Tldr; what are the adverse affects of Germany’s mercantilist policy that are detectable on an individual (Household) level (as opposed to a Corporate or FIRE sectors, that are presumably doing fine)? What is the same and what is different about Switzerland?

It isn’t only growth that is being killed by this absurd balanced budget position. Aldershot has sold a residential street to a company who can charge residents to park in front of their own houses. This was a public street. You couldn’t make it up. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2018/may/28/parking-enforcement-private-law-fines-penalties-appeal. Residents of this street now can be given parking fines for parking in front of their own houses.

In another council district, in a council housing area some streets were sold for private car parking and a disabled individual has to park 5 minutes walk from his own home. I understand that he doesn’t have the funds to purchase the right to park in the street on which he lives.

One could be forgiven for concluding that the fanatics in the Tory government want the public sector to disappear, or at least that part of it that doesn’t suit them. This bullshit story, and others, put out by the likes of the IFS is propping up a grotesque system of unjustified entitlement. The idiotic thing about it is that it is unsustainable, which isn’t to say that it can’t exist beyond what normally one might think would be its sell by date. I thought we would reach that by now. But it seems not.

Addendum:

As I mentioned, balanced fiscal budget positions can kill things other than growth. They seem to be able to kill quality in some products. Take women’s clothing. My partner has heard many people in Marks & Spencers say that they wouldn’t buy some item of clothing because it was crap, that it wasn’t as good as what they could have bought in M&S a few years ago. Recently, M&S have decided to close a number of stores and have indicated that they may imitate Asda in some way, the British Walmart. One reason for M&S not being able to compete seems to be that they have been financialized and no longer think that the company mission is to produce a quality product at a given price point. Any response to difficulty appears to be financial in one way or another. I would have thought that even the rich would have difficulty obtaining quality goods in a system like this, eventually.

The Bank of England can manage any liquidity issues (increasing bank reserves) by simply providing a support rate on the excess overnight reserves, a practice that has become common around the world since the GFC saw central bank balance sheets expand dramatically.

The two operations – issuing a formal debt instrument and paying a support rate on excess reserves – are identical in terms of flows. Bill Mittchell [bold added]

Yet you call the former “corporate welfare”, Bill, but not the latter?

Being risk-free, the debt of a monetary sovereign should yield AT MOST 0% or else we have welfare proportional to account balance, i.e. welfare for the banks, credit unions, etc. and the rich.

And that maximum return of 0% should apply to the longest maturity debt of a monetary sovereign; on-demand account balances at the Central Bank, aka “reserves” in the case of banks, having 0 maturity wait should have interest well into negative territory.

And yes, the banks will try to pass on that negative interest rate on their reserves to depositors.

But that’s just another reason why all citizens should be allowed to have individual checking/debit accounts at the Central Bank itself; said accounts being negative-interest-free up to, say, $250,000 US.

Good blog.

Neoliberal freak show.

“Behind The Facade – Service Shenanigans

Thirty Years of the Mental Health Services – Mostly in North Wales”

Someone who appears to have an insight into the workings of part of the U.K.’s N.H.S.?

Google Dr Sally Baker.

@Deborah

“For example, dear reader, if you were forced to give Mr S £1,000 would you rather pay with PayPal, Visa or cash?”

Very considerate of the Kings Fund to ask, but I’ll take any of those, thanks! ; ))

After I read this ridiculous report I emailed the Chief Economist of the Health Foundation Anita Charlesworth setting out the ‘ spend and tax ‘ reality as opposed to the ‘ tax and spend ‘ fiction and just as the government did to bail out the banks it could create money on a computer ( or as the BofE like to say ‘ electronically’ ) , but answer came there none . On previous occasions when the IFS have spouted their nonsense I have written To Paul Johnson, but he doesn’t reply either. I also emailed Sarah Sands the editor of the BBC Today programme to the same effect and again no reply, but I am following that one up with an email to Tony Hall the Director General complaining that as a licence payer I am entitled to at the very least the courtesy of a reply even of the ‘ brush – off ‘ type. I’ve also written to my MP Bim Afolami ( Conservative Hitchin and Harpenden ) . He will reply , but I don’t expect anything other than some version of the current party line. Those of us who are not economists, but like me, just members of the public who have spent some time digging into this question of money creation and destruction and taxation have come to realise the high priests of the flat earth orthodoxy will cling to this fiction until reality finally

breaks through which it will because the entire history of Sapiens on this planet says so .

Is is possible through mathematical modelling to estimate how much govt spending could be increased before hitting the inflation barrier? Would this be enough to cover the requred NHS increase? Assuming the govt goes the whole MMT hog and over a couple of years increases spending to the inflation barrier, isnt this just a one off ” dividend” , since any further rise in govmt spending would then require an increase in taxation or cuts somewhere else? So after that initial bonus, dont you just get back to the same place again? I am not saying that a one-off bonus isnt worth having mind you, whatever is is. A lot? Not much? Anyone know?