It is true that all big cities have areas of poverty that is visible from…

The Europhile Left use Jacobin response to strengthen our Brexit case

Regular readers will recall that Thomas Fazi and I published an article in the Jacobin magazine (April 29, 2018) – Why the Left Should Embrace Brexit – which considered the Brexit issue and provided an up-to-date (with the data) case against the on-going hysteria that Britain is about to fall off some massive cliff as a result of its democratically-arrived at decision to exit the neoliberal contrivance that the European Union has become. There was an hysterical response on social media to the article, which I considered in this blog post a few days later – The Europhile Left loses the plot (May 1, 2018). In recent days, two British-based academics have provided a more thoughtful response in the Jacobin magazine (May 18, 2018) – Caution on “Lexit”. Here is a response which was co-written with Thomas. As a general observation, I noted some prominent progressive voices citing their attack on us enthusiastically, one even suggesting it landed “some good punches” after taking “a while to warm up”. Well, I can assure Andrew that my face (nor Thomas’s) was the slightest bit puffy after reading the critique.

The response by Bruno Bonizzi and Jo Michell, though interesting largely rests on straw person arguments, false claims and the same kind of muddled thinking that we exposed in our original article.

One suspects though that there is a lot of common ground – given they are “sympathetic” to the “two main points” we raise in our original article:

1. “that many of the UK’s current economic problems have domestic causes and are not the result of the Brexit Brexit referendum”.

2. “the benefits of EU membership have been overstated”.

But where we fundamentally digress is that Bonizzi and Michell do not think that Brexit “provides a clear opportunity for implementation of progressive policy”.

At the outset, Thomas and I have been consistent on this issue both in our individual writing and in our many joint publications now.

The position needs stating clearly.

Brexit might turn out to be a total disaster for Britain if the Right stay in government and harden their neoliberal austerity bias.

If leaving the European Union provides a dynamic to renew and strengthen what is at present a fractured Right polity, then we would be the first to say it will end badly.

But what we have consistently argued is that there is a massive opportunity created by Brexit for British Labour to articulate a restated progressive voice by rejecting its neoliberal Blairite past.

We know there is a lot of debate and opinions about what membership of the EU actually allows Britain to do or not to do (for example, nationalisation of the railways etc).

The legalities are far from clear and would be finally adjudicated by the European Court of Justice rather than the British people via its legislature. That alone should tell the Left that EU membership compromises British democracy.

But Brexit means that the legal uncertainties are resolved and British Labour could confidently define a progressive path that allowed it to use its currency sovereignty to advance the well-being of all British citizens and residents.

Whether it would have the capacity to step up to that task is another matter and neither Thomas nor myself have suggested it is inevitable that will demonstrate the required leadership to succeed.

The failure of mainstream macroeconomics …

Bonizzi and Michell begin their critique by agreeing with us that the:

Predictions of immediate recession following the referendum … were clearly overstated to make political gains.

But then they say that our claim that the economics professions should hang its head in shame – for the inaccuracy of its economic predictions in case of a Leave victory – is unfair, since these predictions were “not endorsed by academic economists” and mostly peddled by “politicians or banks”.

They argue that the “academics confined their attention to the long-run effects”.

That statement is incorrect.

On May 23, 2016, just a month before the Referendum, the UCL Department of Economics issued a press release – UCL economists warn of historic economic risks from Brexit – which reported that:

47 economists from the UCL Department of Economics, ranked first in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework, have added their voices to a warning that the economic costs of Brexit would be high.

The 47 have together signed a statement now agreed to by over 200 other economists.

And what did they state?

Focusing entirely on the economics, we consider that it would be a major mistake for the UK to leave the European Union …

The uncertainty over precisely what kind of relationship the UK would find itself in with the EU and the rest of the world would also weigh heavily for many years. In addition, there is a sizeable risk of a short-term shock to confidence if we were to see a Leave vote on June 23rd. The Bank of England has signalled this concern clearly, and we share it.

These signatures confirm the breadth of the consensus among academic economists that Brexit would pose historic economic risks.

This letter was published in the Times newspaper and so received widespread coverage.

So nothing exclusively long-run about that.

And nothing “entirely” economics about that. They were trying to influence the Referendum outcome in favour of Remain.

On May 10, 2016, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research published its – Commentary – The economic consequences of leaving the EU – which said that:

… there is a degree … of consensus that leaving the EU would depress UK economic activity in both the short term (via uncertainty) and the long term (via trade).

This study was enthusiastically promoted two days later (May 12, 2016) by well-known British academic Simon Wren-Lewis who used it as authority to state “doesn’t everyone already know that nearly all economists think Brexit would have significant costs” (Source).

Further, on May 28, 2016 a few weeks before the Referendum, the British Observer published an article – Economists overwhelmingly reject Brexit in boost for Cameron – which reported on an opinion poll that the Guardian group had commissioned.

The Ipsos MORI poll – Economists’ Views on Brexit – surveyed “members of the Royal Economic Society and the Society of Business Economists”.

The survey recorded 639 responses from economists and asked them to differentiate the likely impacts of Brexit over the next 5 years (so short- to medium-term) and over 10-20 years (longer-term).

The sample of 639 included 366 (57 per cent) academic economists, the rest, largely, being economists working in the private or public sectors or for ‘think-tanks’ or charitable organisations.

Of the academic responses 258 out of 366 claimed that Brexit increased the risk of a “serious negative shock in the next 5 years”.

Of all the responses received 436 out of 639 claimed that Brexit increased the risk of a “serious negative shock in the next 5 years”.

In other words, the academic opinion was dominant that the short- to medium-term consequences were seriously negative.

But, moreover, in our article we criticised the mainstream macroeconomics profession in general and consider it to be a relatively cohesive group – whether they be academic or otherwise – united by a consistent approach to economic analysis.

In this blog post – Bank of England Groupthink exposed (January 8, 2015) – I discussed how Olivier Blanchard (who at the time was the chief economist at the IMF) wrote in his August 2008 article – The State of Macro – that research articles in macroeconomics now:

… look very similar to each other in structure, and very different from the way they did thirty years ago …

He said that they now follow “strict, haiku-like, rules”.

Graduate students are trained to follow these ‘haiku-like’ rules, that govern an economics paper’s chance of publication success and conditions type of techniques and methodology that is deployed.

I also considered the New Keynesian consensus that dominates the economics profession in this blog post – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time (September 18, 2009).

So the shockingly inaccurate short-term forecasts that the British Treasury and the Bank of England put out in the leadup to the Referendum cannot seriously be considered not exempt the mainstream macroeconomists who either produced the reports or supported them in the media in one way or another from damning criticism.

Which is what we did.

And in an event at London’s Institute for Government (January 5, 2017) – Andy Haldane in conversation – Bank of England’s chief economist admitted that:

… his profession is in crisis having railed to forsee the 2008 financial crash and having misjudged the impact of the Brexit vote.

The reporting of the event ((Source) said that:

Blaming the failure of economic models to cope with “irrational behaviour” in the modern era, the economist said the profession needed to adapt to regain the trust of the public and politicians.

Haldane himself said “the models we had were rather narrow and fragile. The problem came when the world was tipped upside down and those models were ill-equipped to making sense of behaviours that were deeply irrational.”

The same models dominate academic research in the field of macroeconomics.

When the editors finalised our Jacobin article they cut out what we thought was some useful detail.

An earlier draft included this detail:

The models used by the British government are called computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, which are informed by gravity models, and – much like their better known cousins, dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models, and other macroeconomic forecasting models – they are highly complex and abstract mathematical models, the results of which are highly sensitive to the numerical calibration of the relationships in the models and the assumptions made about, for example, technology effects (‘returns to scale’). The models are notoriously unreliable and easily manipulated to achieve whatever outcome one desires. The British government has refused to release the technical aspects of their CGE modelling, which suggests they do not want independent analysts examining their ‘black box’ assumptions.

The point is that these models are uniformly used by mainstream macroeconomists within and outside the academy and have produced ridiculous results over many years.

They failed to predict the GFC, even though it was obvious to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists as early as the late 1990s that a crisis was brewing.

They then failed to predict the depth of the negative impacts of austerity – remember the mantra “growth friendly austerity” or “fiscal contraction expansion”.

And they catastrophically failed in relation to the short-run impacts of the Brexit vote.

There is a consistent history of failure by mainstream macroeconomics to concur with the evidence.

Which makes it rather odd that Bonizzi and Michell would hold it out as a criticism of us that we:

… conflate these politically driven Brexit predictions with the problems of mainstream macro modelling and economists’ failure to predict the 2008 crisis.

Apparently, that is a “sleight of hand” on our behalf.

I don’t think the millions who lost their jobs during the GFC (many of who are still unemployed) despite the mainstream macroeconomists gloating that the ‘business cycle was dead’ and we were now in a ‘great moderation’ would think there was any ‘conjuring’ going on when we criticise the accuracy of the economists’ models.

Come Brexit – same models, same approach, same catastrophic errors – no conjuring on our behalf.

This criticim by Bonizzi and Michell is just one of countless examples that undermine the validity of their attack on us.

The linked to a Financial Times article (April 11, 2017) – Economists point finger of blame over Brexit forecasts – which reported on the Royal Economic Society annual conference, where some academic economists tried to backpeddle and absolve themselves of blame over the shockingly inaccurate Brexit forecasts.

Revisionism.

As we noted above, academic economists also came out in the press before the election claiming there would be ‘serious negative short-term results’ from Brexit.

Its on the public record. One can admit they were wrong but not that they didn’t say it.

Taking all that into account, Bonizzi and Michell’s defense of the economics professions is thus very hard to comprehend.

Just after the Referendum result, Ann Pettifor, who admitted to voting ‘Remain’, reflected on the outcome and summarised what most critical (progressive) economists now take for granted (Source):

We … call for an urgent, independent, public inquiry into the economics profession, its role in precipitating both the financial crisis of 2007-9, and the subsequent very slow ‘recovery’. Finally the role of the profession in the run up to the British European referendum campaign …

Economists have once again proved themselves not only irrelevant, but a dangerous irrelevance ….

Economists led the way to financial liberalisation of the past 40 years, which led to soaring levels of debt, crises and financial ruin. Economists dictated the terms for austerity that has so harmed the economy and society over the past years. As the policies have failed, the vast majority of economists have refused to concede wrongdoing, nor have societies been offered alternative economics policies …

Remain chose to focus on the economy – to the exclusion of almost all else. All the heavyweights of the economics profession – 10 Nobel Prize-winning economists, the OECD, the IMF, the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the NIESR, the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the London School of Economics – were wheeled out to warn the British people of economic facts known, and understood apparently, only to “experts”. The Financial Times amplified their voices and repeated their dire threats and warnings over and over.

But the “experts” and the economic stories they tell, have been well and truly walloped by the result of this referendum.

… the people are not to blame.

The economics profession, and their friends amongst the world’s financial elites, are to blame. They engineered their own political and financial bail-outs after the grave financial crisis of 2007-9. Economists cheered on politicians and effectively urged them to transfer the burden of losses on to those most innocent of the crisis …

Those powerful words link the neoliberal period to a series of catastrophes – including the GFC and the failed Brexit predictions.

For Bonizzi and Michell to claim we used “sleight of hand” to link the shocking Brexit predictions and other failures of “mainstream macro modelling” (including “failure to predict the 2008 crisis”) is simply a stunning denial of history and fact.

Post-Brexit Britain is not booming

Bonizzi and Michell then criticise us for “trying to paint the post-referendum period as a boom”.

If you re-read out article you will not find any statement that would suggest Britain is booming. We have never claimed that that the British economic situation is idyllic.

In fact we write that:

… the UK continues to face serious economic problems – suppressed domestic demand, ballooning private debt, decaying infrastructure, and deindustrialization …

But we simply claimed that “these have nothing to do with Brexit, but are instead the result of the neoliberal economic policies pursued by successive British governments in recent decades, including the current Conservative government.”

We clearly based our criticism of the scandalously inaccurate modelling pre-Brexit on an appraisal of the facts that are available some two years since the Referendum.

It is obvious that:

1. GDP has grown by 3.7 per cent since the Vote.

2. Unemployment is lower.

3. British manufacturing is growing strongly – via better world trade conditions.

4. Capital formation was strong in 2017 (highest of any G7 country).

We don’t call that a boom. We simply state the facts and counter pose them against what the mainstream economists were predicting would happen – almost the opposite of what has happened.

So, to their discredit, Bonizzi and Michell are just making stuff up when they make that claim about us.

They specifically take exception to our statement:

Total investment spending in the UK – which includes both public and private investment – was the highest of any G7 country during 2017 …

They write that this is:

… is simply incorrect. Investment growth was high, but from a low base. By historical standards, investment spending remains low, and is in fact the lowest among G7 countries as a percentage of GDP.

And there is the sleight of hand!

First, note they throw in some cloud – “from a low base” – to sow doubt about the veracity of our claim. Of course, it is from a low base. The UK endured a policy-driven recession for many quarters which derailed capital formation.

We all know that and it is irrelevant for the point we were making about the growth of British investment post-Referendum.

Second, the proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

In our article, we linked to a Financial Times report (March 29, 2018) – UK investment spending leaves G7 rivals trailing – to provide an easy to access evidence trail.

That article was summarising the latest ONS data on British investment:

Annual growth in investment spending in the UK was the highest of any G7 country during 2017, according to figures published by the Office for National Statistics on Friday …

The figures suggest that uncertainty over the outcome of the Brexit negotiations has not chilled overall investment spending in the UK.

Was that Financial Times article reporting accurately?

Well, lets go to the source and see what the Office of National Statistics published.

The specific Office of National Statistics release (March 30, 2018) – Business investment in the UK, revised: October to December 2017 – provided some “International comparisons of GFCF” as part of that release.

The ONS conclude:

Between 2016 and 2017, the UK had the strongest growth in gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) of any G7 nation at 4.0%

QED!

Here is the graph:

Bonizzi and Michell’s sleight of hand?

Note that Bonizzi and Michell say that British investment spending “is in fact the lowest among G7 countries as a percentage of GDP” (our emphasis added).

Our article was talking about investment growth not investment as a proportion of GDP. They are two different things altogether and so why try to blur the argument? Well it is because they did not have a legitimate point and so they made one up.

Note also that the investment ratio (as a proportion of GDP) also hasn’t declined since the Brexit vote.

Trade graphs

Bonizzi and Michell agree with us that “the economic benefits of single-market membership have been overstated”.

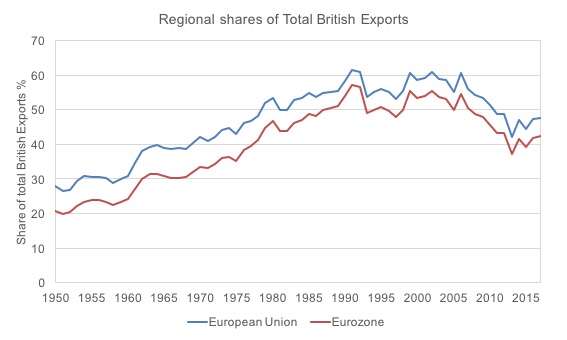

But they take exception to one of the graphs we produced (reproduced here).

This graph was originally produced for my (Bill) blog post – The facts suggest Britain is not as reliant on EU as the Remain camp claim (April 16, 2018) – and I fed it into our Jacobin article.

Two things are obvious from the graph:

1. There was no particular acceleration in British exports as a share of their total exports to the EU or to the nations now comprising the Member States of the Eurozone after it accessed membership of the EU in 1973.

2. After the introduction of the Single Market, twenty years later, the British share of exports going to the EU and the EMU flattened and after the 2005 (pre-GFC) started to decline rather sharply.

In other words, Britain has been diversifying its exports and is less reliant on the EU than it was say in the early 1990s.

Exports to China have risen from virtually zero in 1973 to 4.8 per cent of the total in 2017, while exports to the EU are falling towards the 1973 levels.

Bonizzi and Michell say we “overemphasize the significance” of it and that the graph “does not imply ‘a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU'”, but only that non-European trade has been growing at a faster pace.

Yes, the graph is about shares rather than levels. We obviously understand that point.

And so we added a further piece of evidence that Bonizzi and Michell deliberately chose to ignore, presumably because they would not then be able to make their erroneous point.

We wrote:

A further observation drawn from the IMF Directions of Trade database is that while global exports have grown by 5 times since 1991 and the advanced economies exports have grown by 3.91 times, the EU exports have only grown by 3.7 times and the Eurozone by 3.4 times.

Thus, in both relative and absolute terms the Single Market has not had the major postive effect that the anti-Brexit lobby would have us believe.

It is, of course, always possible that without the Single Market, outcomes would have been much worse. But that conjecture would be difficult to sustain.

Bonizzi and Michell try to argue otherwise, saying that “we do not know what would have happened if the UK had remained outside the EU. It is perfectly plausible that trade would have declined.”

How is it perfectly plausible given the massive growth of South and East Asia, and the growing contribution of that growth to British trade?

Countries such as Australia, which had relied on Britain for trade under Commonwealth agreements and was abandoned when Britain joined the EU in 1972, relatively quickly reoriented their external focus to Asia and trade has boomed ever since.

It is much more plausible that in the absence of EU membership, British trade would have similarly expanded.

So the evidence does support the Cambridge study study published by the Centre for Business Research (CBR) at Cambridge University, which we quote, that suggests “a negligible advantage to the UK of being a member of the EU” in this regard.

Curiously, Bonizzi and Michell then criticise us for claiming that we:

… go on to argue that trade is not beneficial.

We actually do not say that in our article.

This is just a straw person argument introduced by them.

What we actually show is that there is no evidence that trade liberalisation (under the ‘free trade’ mantra) does no necessarily lead to increased trade, as the neoliberal era – and as the single market – shows.

The two things are very different.

Bonizzi and Michell get muddled

Then the muddled thinking kicks in.

Bonizzi and Michell claim that:

… had the UK remained outside the single market, either it would have complied with the ongoing development of EU regulatory structures in order to maintain and develop its pan-European and global production chains, or faced gradual disintegration with the European economy.

In other words, Bonizzi and Michell are saying that the UK could have continued to trade perfectly well with the EU without joining the EU (as in the case of say, Norway).

So how can they also claim that “it is perfectly plausible that trade would have declined” had the UK not joined the single market?

This is classic Left-TINA thinking which goes like this: As a result of global capitalism, nations have lost significant sovereignty and so they have to accept either everything (that is, full harmonisation and financial integration) or autarchy (frozen out).

Apparently, there is no middle ground is possible in this narrative.

The evidence of many nations clearly shows there is middle ground.

Brexit and deindustrialisation

Bonizzi and Michell further claim that we ignore the fact that Brexit will necessarily entail a restructuring of British capitalism, which in turn implies economic costs, especially in the short term.

However, the idea that we just ignore adjustment costs is ludicrous.

Any major legal changes within an economy create ‘adjustment costs’. Our position is clear.

If the ‘free market’ narrative wins out in post-Brexit Britain then there will be massive costs.

However, we believe that this restructuring – especially if steered by a future Labour government – could prove positive for the British economy.

In this regard, we quoted The Economist article (February 8, 2018) – Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom – which noted that despite the uncertainty concerning the negotiations with the EU:

… Britain’s long-suffering makers are enjoying a once-in-a-generation boom … manufacturing is seeing its strongest growth since the late 1990s …

We noted that this virtuous cycle has been largely due to a growing demand for British exports, which are reaping the benefits of the lower pound and improved world trade conditions.

But, further, as The Economist notes that Brexit-induced shifts have engendered a much-needed “rebalance towards the manufacturing sector.”

And they say this will mean that the British economy will be “Relying less on boom-and-bust financial services” which “will put the economy on a surer footing”.

All of that discussion is in our Jacobin article and so Bonizzi and Michell’s claim that we ignore it is ridiculous.

We also provide other evidence trails including:

1. Survey evidence from the British manufacturers’ association EEF (Source).

2. Citation of a new a report by Heathrow Airport.

3. And the research from the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR), cited above.

4. Links to an Op Ed by Guardian Economics editor Larry Elliott who in his article (August 20, 2016) – Brexit Armageddon was a terrifying vision – but it simply hasn’t happened – wrote that in many respects:

Brexit has been a help. It has forced the government to take a long, hard look at the British economy – something that would not have happened without the shock administered by the referendum. It’s brought home the fact that most of Britain feels disconnected from the economic story peddled by successive governments.

For decades, there’s been a tendency for businesses to meet rising demand by employing cheap labour rather than by investing in modern equipment. Large chunks of the economy are characterised by low skills, low wages, and low productivity. As the Resolution Foundation noted this week, companies that rely on the ability to import low-cost employees from the EU are going to have to rethink their business models. This is not necessarily a bad thing.

The government has responded to Brexit by soft-pedalling on austerity, by contemplating spending more on infrastructure and by committing itself to an industrial strategy. A degree of scepticism is warranted here. The referendum has made change possible: it doesn’t guarantee it will happen.

By way of summary, our Jacobin article provided significant external resources to support our argument that a properly designed policy intervention in post-Brexit Britain can generate beneficial outcomes contrary to the long-run forecasts of doom and gloom coming from the mainstream economists.

Brexit is a Right-wing plot or the work of racists – how did we overlook that!

Bonizzi and Michell then accuse us of not acknowledging:

… that Brexit is being driven by a UK government with broadly two factions: center-right Remainers and, further to the right, a Leave bloc populated with libertarian fantasists dreaming of an ultra-deregulated, off-shore, low-tax utopia.

Hello! Is anyone there?

The fact is that we don’t ignore this point either.

As we outline in our new book Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017) – we simply do not subscribe to the determinism that paralyses the Left discourse.

The notion that leaving the EU will “inevitably” benefit the Right is not new. In fact it was a common argument of the Left even before the referendum, with claims that a Leave victory would have “inevitably” benefited the right.

It is the same sort of argument that the Left use when discussing any sort of ‘Exit’ – Greece, etc.

Well, in the two years since the Leave vote the opposite has happened.

As John Weeks, a Remainer, wrote in his openDemocracy article (July 31, 2017) – No Bregrets: does Brexit hold hope for progressives after all?:

… pro-EU progressives will find it hard to deny that the referendum result we fought to prevent has led to events beyond our most optimistic hopes, with the fall of the Cameron government and stunning success of the Labour Party in the 2017 general election. I deeply regret leaving the European Union, but must accept that the probability is great that the June 2016 referendum will in due course result in a UK government committed to social democracy, not neoliberalism.

A very powerful statement. Come in Jeremy Corbyn and his Labour team.

One would have to be blind not to see that Corbyn’s rise is also the result of a process fo repoliticisation engendered by Brexit.

Similarly, Bonizzi and Michell reprimand us for ignoring that “the referendum result was driven by anti-immigrant sentiment”.

We don’t ignore that; we simply believe that Brexit is the symptom not the cause, and that reversing Brexit won’t eliminate the root causes of the phenomenon. In fact, the contrary is likely to happen.

The EU utopia … how did we overlook that!

Finally, Bonizzi and Michell argue that we overlook the “progressive” benefits of EU membership, including – they write:

… social protection, environmental regulation, and academic and scientific cooperation.

We don’t ignore that EU membership has its benefits.

We simply believe that:

1. The costs outweigh the benefits (self-evidently so in the case of eurozone countries).

2. Many of the benefits cited by the authors – scientific cooperation, the Erasmus programme, etc. – could be enjoyed even without the economic super-structure of the EU, as a result of international agreements between countries.

For example, Australian researchers have no trouble creating very robust and effective working relationships with academics in Europe. Not being part of the EU has never stopped us doing that.

As for the notion that the EU defends “social protection”, perhaps we should ask the people of Greece if they agree, just as we should ask the people of Norway if a country can enjoy high levels of social protection outside the EU.

More in general, not only have EU institutions overseen in recent years a brutal assault on the social and economic rights of the citizens of Europe, particularly in the periphery; they have also proven utterly powerless to prevent member states (such as Hungary and Romania) from violating the rights of their citizens and/or from disregarding some of the basic tenets of the EU, such as the Schengen Treaty.

Hence, the contention by Bonizzi and Michell that the EU is the only thing preventing the UK from plunging into a quasi-fascist dystopia is untenable.

The fate of Britain post-Brexit will depend on the strength of its democracy and the mobilisation of progressive narratives.

Finally, the Bonizzi and Michell claim that the argument we present in the original Jacobin article:

… is based on a non-sequitur: the benefits of the EU and the costs of leaving are overstated, therefore leaving is the only progressive option. They offer nothing to bridge the gap between premise and conclusion – other than some vague comments about nationalization and state aid rules.

Our argument is, in fact, very simple and hinges on two crucial points:

1. Britain would have much more space to pursue radical economic measures (such as those foreseen in Corbyn’s manifesto) outside than inside the EU.

At present there is a lot of legal argument advanced by the Left about what Britain can and cannot do within EU legislative frameworks. The arguments claim that there is nothing in EU law that would restrict Corbyn from introducing a very radical agenda and wiping out neoliberalism in British policy.

We disagree, but that is a separate argument. However, what Brexit will deliver is freedom from the uncertainty of all this legal interpration and recourse to the European Court of Justice.

In other words, for good or bad, Britain’s legislature will be uncompromised by these external rules and courts.

2. A soft Brexit or even worse a Brexit In Name Only (BINO) would kill much of the political energy hitherto engineered by Brexit and harnessed by Corbyn.

As Richard Tuck wrote (August 21, 2017) in his Op Ed – Long read: Brexit is a prize within reach for the British left:

If I am right in supposing that this new surge in left-wing politics is the result of Brexit, it would be suicidal to overturn it. We can see the dangers of doing so very clearly in the case of the working-class UKIP voters, particularly in the North, who felt it was now safe to return to Labour; but it is also dangerous indirectly and in the long term for the newly-energised younger voters of the South. They may to some degree support the EU, but their new energy is a product of Brexit, and not in the sense that it is merely a reaction to it. Like everyone else, they have sensed the opening-up of possibilities long denied to them, and even if they want the EU they surely do not want the return to power of the kind of politician the EU necessarily breeds.

We concur with that view.

Conclusion

Finally, it is only in the last paragraph that Bonizzi and Michell reveal the bias that informs their whole article:

Although we are under no illusions as to the shortcomings of the EU, we remain committed to the view that these are overshadowed by the political risks of fragmentation. A far-right hard Brexit is a more likely scenario than a progressive one. The progressive position is, while accepting the result of the referendum, to seek to maintain ties with Europe and work with other progressives towards the goal of reform.

This is the nub of the conflict within the Left.

In Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, 2017) – we provide a coherent evidence-based argument to show that we do not consider progressive reform of the EU to be an option and thus our approach to Brexit is obviously informed by that.

Just like their belief in the EU’s reformability informs their opposition to Brexit.

Our writing (together and individually) has regularly updated readers on developments within Europe – most recently – Die schwarze Null continues to haunt Europe (May 21, 2018) – which demonstrates that the Europhile Left’s hope that meaningful progressive reform is just around the corner is a pipe dream.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“However, what Brexit will deliver is freedom from the uncertainty of all this legal interpration and recourse to the European Court of Justice.”

And most importantly recourse to the ECJ *by corporations and individuals* allowing them to overrule the decisions of parliament.

In the UK our political system is protected by a simple rule – that no parliament can bind a successor. That means what parliament says goes, and if people don’t like that they vote the other lot in who can change *anything*. So aberrations like PFI cannot exist in a parliamentary system. If one parliament signs an appalling deal, then a subsequent parliament can cancel that – summarily if it decides to.

That places parliament and the people above corporations. The EU reverses that and puts corporations ahead of parliament and the people – and those supposedly on the left lap that corporatism up.

Only a group who realise they have no political narrative that can win over the general population would appeal to a higher law system that puts corporations ahead of the people. And continue to do so after they have lost that argument in a national vote. At that point it moves from a political argument to a religious faith.

BTW,

Has anyone seen this article on Italy?

https://gefira.org/en/2017/10/14/italys-parallel-fiscal-currency-all-you-need-to-know/

It certainly draws a smile.

Sorry, OT, but I just couldn’t believe the idiocy of this story in today’s Graun:

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/22/attorney-general-defies-call-to-give-400m-windfall-to-uk-charities

…both on the part of the Attorney General, and, perhaps even more so… on the initial, anonymous, donor. The stupidity of both parties is infuriating.

When it comes to the whole concept of “paying back the ‘National Debt’ “, doesn’t anyone even think to ask themselves that if the holders of Gilts had preferred to keep their funds in cash, they wouldn’t have bothered to buy the bloody Gilts in the first place!

Thank you for another superb article Bill. There is one major issue that I hope you can address. That is the supposedly dangerous problem of a hard Irish border. This is regularly raised as perhaps the single most telling element against Brexit. What are your thoughts/solutions?

Might I say one thing in defense of one of the critics’ points? A slightly longer extract from the Mitchell & Fazi Jacobin article is:

The second sentence really needs another “growth” after “Total investment spending”. This is clearly what is meant by the context. But that is not what the fragment of the second sentence up to the number 2017 says, that part that is quoted above in this post, which actually is the critics’ misreading. That whole sentence, literally read without “growth”, seems to say something ridiculous and untrue, that even though investment in Britain was 4% of the previous year, that is, it fell by 96%, it was still the highest in the G7!

So they were misinterpreting a sentence that did have a defect, but the the literal reading of the whole is so silly, that should have been a red flag to look closer. Still, “sleight of hand” or “making things up” is too strong imho.

I’m beginning to get a better appreciation of the policy constraints posed upon constituent states of the EU. Thank you for that. Sadly, I’m rather less sanguine about the prospects of a shift in attitudes toward deficit and debt among the UK electorate anytime soon.

(I hope it won’t be considered churlish of me to point out that the expression so often bastardized as “the proof is in the pudding” ought to read, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating” /pedantry)

“That is the supposedly dangerous problem of a hard Irish border. This is regularly raised as perhaps the single most telling element against Brexit. What are your thoughts/solutions?”

It’s a political non-sequitur.

As ever, we should focus on the real goods and services. So given that every sovereign power in the area has said there will be no physical border, who is going to tax their population, obtain the resources, hire and instruct worker to construct infrastructure?

Since nobody will raise the resources to build anything, nothing will be built and there is no power on earth that can require anything else. Nothing is actually enforceable against anybody.

So the whole thing is political grandstanding and will be dealt with in the traditional fashion – with a blind eye turned and a whole heap of fudge.

Ireland is an island – as is Great Britain. Any technical discrepancies will be patched up at the ports and otherwise quietly ignored.

Michael Hudson, in an interview with Chris Hedges discusses the power of the corporate world and its minions to continuously treat the 99% as disposable subjects. The inevitable conclusion is that the EU is so sold out on that argument, Brexit may be the only way to extricate the British public from the neo-liberal straightjacket;

https://videosenglish.telesurtv.net/video/523415/days-of-revolt-523415/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=89&v=6KZJBgihWcg

In fact the whole world economy is in dire straights.

Hello,

Great post.

The private sector balance in the Uk is about minus 5.5 of GDP at the moment due to the surplus budget and the external deficit (lots of real benefits tho).

Private credit growth is about 3.5% of GDP.

This is one of the weakest private sectoral balances on the planet.

I wonder how long that can go on for before recession comes? Until credit growth falls over?