Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Workers’ parties in NZ and Australia compete to be the most neoliberal

The Italian elections were held last Sunday (March 4, 2018) and the results are devastating for the Europhiles that think that the EU and the Eurozone, in particular, can be reformed to bring the people together in some sort of democratic paradise. Anti-establishment parties including the far right Lega Nord (who want to expel all migrants) have made spectacular gains. This follows elections in several nations where rather extreme results have emerged. What is apparent is that social democratic parties have started to lose electoral supports in large swathes and, in some, cases are now diminished and ruined forces. After hearing what the Shadow Treasurer in Australia said yesterday I can only hope the same electoral whitewash of the Australian Labor Party occurs at the next election. The message from the various national elections is pretty clear. Voters have seen through all the neoliberal nonsense that they have been bombarded with over the last decades and the miserable actual outcomes that have followed in terms of things that matter for peoples’ prosperity – jobs, real wages growth, income security, public services and infrastructure etc. They are sick of seeing the top-end-of-town walk off with the largesse while government’s attack the poorer elements in the name of ‘budget repair’. The neoliberals have pushed their luck to far. Sunday’s Italian result is just part of the evidence mounting to support that view. But, back in the Southern Hemisphere the Labour government in New Zealand the Labor opposition in Australia do not seem to have understood the trends. They are still thinking it is clever to ape the neoliberal nonsense about fiscal surpluses, AAA credit ratings and war chests to help fight future recessions. Sad sad sad.

In the Anglo world things go from bad to worse.

The newly-elected New Zealand Prime Minister was in Australia on Friday for the Australia-New Zealand Leadership Forum in Sydney.

This is an odd gathering where the respective leaders try to be nice to each other and a coterie of hangers on ‘network’.

It is a sort-of downmarket Davos with business types crawling around looking for ways to lobby government officials to extend the current ‘privatise the gains/socialise the losses’ agenda.

The business community clearly feeds of the state no matter what they say in public about the need for smaller government.

The downsizing of government they keep calling for never applies to the extensive corporate welfare they receive. Only to the income support schemes etc that the most disadvantaged in our communities might be able to tease out of the government after jumping through a ridiculous array of humiliating hoops (like, work tests etc).

Anyway, the New Zealand leader clearly is not in tune with the way in which national electorates are abandoning parties like hers.

In her speech (March 5, 2018) – Ardern speech to Australia-New Zealand Leadership Forum – the NZ Prime Minister started off ‘all folksy’, which is par for the course in these talkfest junket events.

Later she turned to fiscal matters.

She said that her “government has an ambitious agenda to improve the wellbeing and living standards of New Zealanders through sustainable, productive and inclusive growth. And we are in the market for good ideas and opportunities on how to best deliver that.”

Then she said this:

By sustainability, we mean budget sustainability – running sustainable surpluses and reducing net debt as a proportion of GDP.

Which means that while she “in the market for good ideas”, she must not have found any yet from her advisors.

This is a ridiculous statement for a national leader to make, much less a Labour Party Prime Minister.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents understand that one cannot unilaterally declare a fiscal surplus to be good and a fiscal deficit to be bad.

Equally, setting a goal of a fiscal surplus, as if it is the only ‘sustainable’ outcome is nonsensical without context.

Long ago, sensible economists knew that there was nothing intrinsically ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about a particular fiscal balance.

The famous US macroeconomist Gardner Ackley commented on a proposed balanced federal budget in the US in 1982 in this way:

The proposed Constitutional Amendment to restrict both federal government deficits and the level of federal government expenditures relative to national income lacks economic or political justification. Its enactment, I believe, would severely damage the ability of the federal government effectively to carry out its responsibilities, and could significantly reduce the welfare of the American people.

The conclusion is as valid today as it was then.

Fiscal policy has to be flexible – expanding and contracting its influence on the economy as the spending patterns of the non-government sector relative to real productive capacity require.

Gardner Ackley also understood how fiscal deficits and the economy interact. He said:

My own position on deficits has always been, and remains, that deficits, per se, are neither good nor bad. There are times when they are not only apppropriate but even highly desirable, and there are times when they are inappropriate and dangerous …

… large deficits in a period of substantially expanding output and employment are dangerous and damaging. They can easily produce excess demand, over-full employment, and escalating inflation.

He listed the recessions that he was familiar with (1954, 1960, 1970-71, 1975, 1981-82) and concluded that imposing fiscal austerity during those times “would be prohibitively costly – in jobs, production and real incomes – and perhaps even impossible to achieve on any terms”.

Note he is relating the fiscal outcome to the circumstances in the economy not to some pre-conceived notion that some balance is desirable and another is not.

Also note that he doesn’t say that when the economy is expanding the fiscal balance should be in surplus. He relates “large deficits” in terms of “excess demand”.

At full employment, it is entirely possible (and likely) that the fiscal position will still be in deficit (given the propensity of the non-government sector to save overall).

Please read my blog post – A voice from the past – budget deficits are neither good nor bad – for more discussion on this point.

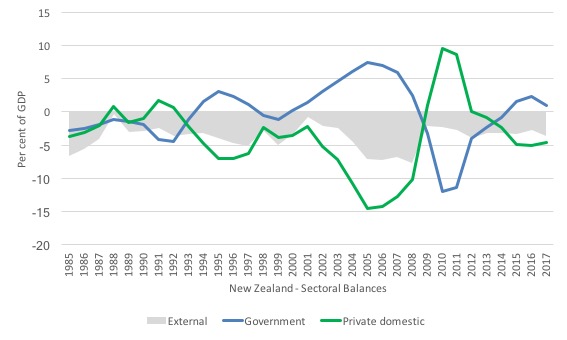

The following graph shows the sectoral balances from 1985 to 2017 (using IMF WEO data). If you do not understand the balances and their interpretation, please read the blog post – Flow-of-funds and sectoral balances (November 24, 2015).

The graph shows the classic pattern.

The facts are these:

1. New Zealand runs a fairly consistent external deficit (averaging 3.8 per cent of GDP between 1985 and 2017), which drains income from the economy (a leakage from the spending flow).

2. As a result (fairly stable external deficit), the government balance and the private domestic balances is almost a mirror image.

When the government runs a surplus, the liquidity squeeze on the private domestic sector pushes it into deficit. That pattern is easy to see.

3. In that environment, if the government runs a fiscal surplus, then the private domestic sector will always run a deficit (increase its indebtedness).

4. Over the period 1985-2017, the private domestic sector has indeed run a deficit on average (3.7 per cent of GDP).

5. In December-quarter 2008, Household debt to disposable income was at 100.4 per cent (Source).

By the September-quarter 2017, the ratio was at record levels of 167.5 per cent.

The fiscal surpluses that started rising in early 2000 to reach 6.9 per cent of GDP in 2006, were accompanied by a surge in the Household debt ratio from 100.1 per cent to 154.8 per cent.

The ratio dropped back a little during the GFC as the government went back into deficit (and took the liquidity squeeze off the private domestic sector) – it dropped to 145.6 per cent in the March-quarter 2012.

Once the NZ government started its renewed austerity push – the debt ratio quickly rose to its new record level, with no end in sight – until it becomes too precarious.

The Reserve Bank of NZ has limited room to move on interest rates because at present the interest-servicing burden is stable because of the low rates. But that will quickly rise to record levels given the stock of debt once the RBNZ starts hiking the rate.

6. In other words, the NZ Labour government is deliberately following a strategy where growth will be driven by the growth in private sector indebtedness.

That cannot be a sustainable strategy.

Eventually, the levels of debt will mean even the slightest change in employment growth (down) or unemployment (up), or interest rates, etc will push many households over the cliff into insolvency.

And to put the rather ‘lacking in empathy’ sectoral balances graph into a more real context, this is a nation that according to the UNICEF – Child Poverty Monitor 2017 – has the following characteristics:

1. Once you exclude the dysfunctional Eurozone, New Zealand has one of the highest labour underutilisation rates within the OECD.

2. 12 per cent (of 135,000) of New Zealand’s children live with material hardship.

3. 290,000 or 27 per cent of New Zealand children live in poverty (relative measure – below 60% of median income).

4. 80,000 or 7 per cent of New Zealand kids live in severe poverty (below 50% of median income).

The Child Poverty 2017 Technical Report tells us that:

Thirteen percent of dependent 0-17 year olds were living in households with the very lowest incomes, below 40% of contemporary median after housing costs, approximately 140,000 children and young people.

The number and proportion of dependent 0-17 year olds living in income-poor households increased significantly between 1988 and 1992, and these figures remain high.

The number and proportion of dependent 0-17 year olds living in households with the most severe income poverty have not declined since 2012.

Previous studies have shown that in 2016, “twice as many children now live below the poverty line than did in 1984 has become New Zealand’s most shameful statistic.”

The Executive Director of Unicef in New Zealand was quoted by the UK Guardian (August 16, 2016) – New Zealand’s most shameful secret: ‘We have normalised child poverty’ – as saying:

We have normalised child poverty as a society – that a certain level of need in a certain part of the population is somehow OK.

The UK Guardian article noted that for “a third of New Zealand children the Kiwi dream of home ownership, stable employment and education is just that – a dream”.

Children from poor families in NZ are malnourished and have fallen sick with “illnesses associated with chronic poverty … including developing world rates of rheumatic fever (virtually unknown by doctors in comparable countries such as Canada and the UK), and respiratory illnesses.”

And the NZ Labour Prime Minister celebrates running fiscal surpluses and thinks they are the exemplar of sustainability.

For some part history of New Zealand neoliberalism and the important role that the New Zealand Labour Party played in its propagation, this blog post is relevant – The comeback of conservative ideology (November 25, 2009).

Governments should not define fiscal sustainability in terms of some particular ‘target’ fiscal balance. Fiscal policy is a tool not an end in itself.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the non-government sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal.

It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap.

However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a fiscal surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs).

But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal balance will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment.

Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

In the case of New Zealand, given its external situation, a continuous fiscal deficit is the only desirable sustainable path for the government to aspire to.

The bottom line is that the Labour Party on both sides of the Tasman Sea have buried their heads in the neoliberal morass and speak weasel words when it comes to fiscal matters.

And on this side of the Tasman … things get worse

The Shadow Labor Treasurer in Australia also made a fool of himself yesterday (March 5, 2018).

His – Address to Per Capita Reform Agenda Series – was a disgrace for a Labour politician to have made.

They are so firmly entrenched in neoliberalism that a major electoral rout is necessary to clear these elements out of the Party.

The function marked the “35th anniversary of the election of the Hawke-Keating Government”, who were elected in March 1983.

This government became a sort of model for the way the neoliberal infestation took over macroeconomic policy thinking in Labour-type parties in the Anglo world.

The Third Way nonsense that marked the destructive Blairite years in Britain owed a lot to the narratives spun by the Hawke-Keating government in Australia.

Bowen will be Australia’s Treasurer when the conservatives finally self-destruct, which they are now doing on a daily basis at present.

Someone called the daily self-created disasters that the conservatives are experiencing something out of a “Mexican telenova” (Source).

Rather than call it the ‘Third Way’, Bowen referred to the Hawke-Keating years as the beginning of the “modern Labor” era – which is code for its shift to neoliberalism.

The “modern labor” approach delivered “the most important period of economic reform in our history” according to Bowen, and provide “lessons” for the current Labor politicians.

Among these ‘reforms’ was the fact that:

… they believed in strong fiscal management. Australia hasn’t had too many surplus years in 73 years since the end of World War II and Paul Keating delivered three of them.

Of course the three surpluses mask the level of difficulty.

They were delivered at a time when our national income was under immense pressure and Australia’s terms of trade hit post-war lows.

Which should tell him everything that the surpluses were totally irresponsible and set Australia up for the worst recession since the 1930s – which eventually emerged in 1991.

At that point, Keating was still Treasurer (soon to become Prime Minister as his ego got the better of him and he knifed Hawke in the back).

Keating told the Australian people that this disastrous recession was “a recession that Australia had to have” (Source).

How Australia ever let that character become Prime Minister is another question.

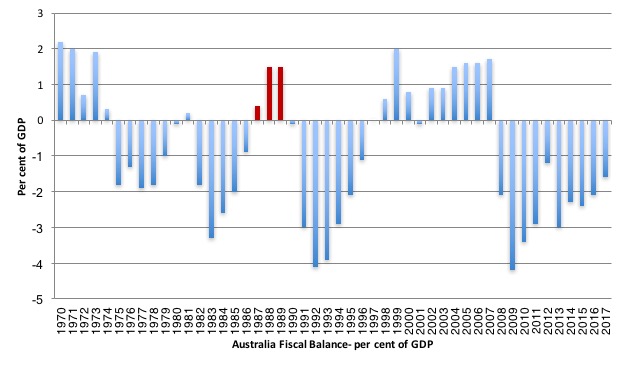

Here is a graph of the fiscal balance in Australia (% of GDP) since 1970-71 to 2017-18 (the last year being an estimate).

The red bars are the three Keating surpluses. They came after two previous years of austerity which was accelerated during the surplus years.

Just like the US, everytime the national government has tried to cut net spending, the economy dives into a recession, which generates even larger deficitis than prevailed before the surplus-obsession was followed.

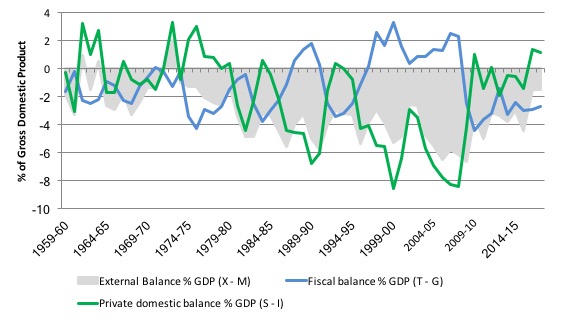

If I told you that Australia at the time (and continuously since the early 1970s) was running an external deficit of around 4.5 per cent (on average), what else would you predict was going on during the years leading up to and including the fiscal surplus years?

Yes, you will conclude that the fact that real GDP was still growing, meant that the private domestic sector was increasingly spending more than it was earning and thus accumulating ever increasing levels of indebtedness.

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

The average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2016-17 has been -3.9 per cent of GDP.

The following graph shows the Australian sectoral balances from the fiscal year 1959-60 to 2016-17. You are all astute at interpreting these type of graphs by now.

The Keating surpluses were in fiscal years 1987-88, 1988-89, and 1989-90 but the austerity squeeze started in 1985-86.

That squeeze marked the beginning of the first phase of the credit binge in the private domestic sector and was the only reason the economy kept growing in the late 1980s.

Unemployment was still very high and the fiscal drag eventually led to the 1991 recession, which pushed the fiscal balance back into deficit.

The second credit binge began as Keating started to tighten fiscal policy in the years following the recession. He handed the conservatives a situation where they could record fiscal surpluses and maintain economic growth as Australian households dived further into debt and financial precariousness.

It was the anathema of sound fiscal policy and should be called out by ‘modern labor’ for what it was, rather than being set as the benchmark for our next Labor government.

Please read my blog post – Household debt is part of a broader problem – be informed (November 22, 2017). – for more discussion on this point.

But Bowen, failing to understand the destructive nature of the surpluses, moved in in his speech to a discussion of “budget repair”.

At that point, I am glad I am freezing my a-off in Helsinki at present because being far away makes the nonsense appear more surreal than dangerous.

Bowen told his audience:

I want to focus the rest of my remarks on our approach to two related themes from that period of reform: tax reform and repairing the Budget.

Firstly, the need to get back to Budget balance …

… [criticising the current Government] … At the end of the Government’s proposed 10 year reduction in corporate tax, the tax cut will be costing the Budget a staggering $15 billion a year. It is a fiscal ram-raid.

And a ram raid at a time when the Budget deficit remains over 1% GDP, 8 times the deficit forecast just a few years ago.

And gross debt has now crashed through the half a trillion dollar mark for the first time in Australia’s history, and is set to get to $684 billion by the end of the medium-term …

They once promised surpluses as big as 1% of GDP.

A fiscal strategy that now states now that the goal is to achieve a strong surplus ‘as soon as possible’.

Under current assumptions, the government will never get there of course.

The Government’s own surpluses aren’t forecast to get above ½ per cent GDP over the entire medium term …

Labor believes in strong fiscal policy and return to surplus and we are prepared to make the tough decisions to do it.

I believe in the return to surplus when conditions allow because locking in the AAA rating reduces borrowing costs and gives more room to fund important social initiatives.

The progressive case for return to surplus also recognises that this would give me and future Treasurers more room to move if we face another global downturn.

And it is dangerous for your health to repeat any more of what he said. Inane is too kind a description.

First, why is there a “need to get back to Budget balance”?

He doesn’t present any coherent case.

Australia has labour underutilisation around 15 per cent.

Our participation rate is below recent peaks (so hidden unemployment is elevated).

Real wages growth is zero or negative.

Poverty rates have risen.

Households are carrying record levels of debt.

Our external sector has been draining growth for nigh on 5 decades.

What part of all that doesn’t Bowen understand?

None of it apparently.

Australia needs to run continuous fiscal deficits of around 2 to 3 per cent and allow cyclical variations around that if our households are to net save.

What Bowen will achieve if he tries to apply this nonsensical approach to the real situation is a major recession and widespread private domestic insolvencies.

Second, it is a disgraceful lie for Bowen to claim that a “return to surplus … gives more room to fund important social initiatives”.

Whether the government is in surplus or not does not alter its capacity to spend today, tomorrow and the next day.

What the surplus does is undermine non-government wealth and squeeze its ability to net save.

Third, the maintenance of AAA ratings from the corrupt rating agencies is irrelevant to the capacity of the Australian government to spend.

Clearly, the government does not even need to issue debt being the currency issuer. A progressive government would end that corporate welfare once and for all.

Further, the government can, through its central bank, always set whatever yields it likes on debt instruments it issues (including at zero).

There is nothing the AAA ratings can do to alter that fact.

Fourth, it is a disgraceful lie to claim that a “return to surplus also recognises that this would give me and future Treasurers more room to move if we face another global downturn.”

There is nothing ‘saved’ from a surplus. Non-government wealth is destroyed. But the government gets nothing. And it needs nothing in order to respond to a future downturn in non-government spending.

How he can frame that lie as a “progressive case” is beyond anything … you put in the relevant word … I am over it!!

Conclusion

This is a dangerous neoliberal mantra being expressed by the future Australia treasurer. The only upside is if he is ever elected to that post, the economy will tank sooner or later under his Treasurership and, hopefully, the electorate will destroy the Labor Party for ever.

Just like voters are doing around the world at present.

The various national elections (with the exception of Britain) have started clearing out the social democratic traitors who mouth these neoliberal weasel words and undermine well-being and prosperity.

It cannot happen soon enough in Australia.

I better go for a walk in the cold to resume my equanimity after all that (it is -11C as I type).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2018 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The only problem is that the Coalition will further entrench Neoliberalism if it is reelected. Bowen sounds like an unreconstructed neoliberal and on present indications he will use a “tax the rich” strategy to try to achieve a surplus.

MMT is such a coherent and logical economic framework that I find it dispiriting that Labor does either not “get it” or is fearful of being attacked by the conservatives along the lines of Abbott’s devastating “debt and deficit” disaster.

I can only hope that Labor in government will be more MMT in reality than their rhetoric suggests.

Of course Australia and NZ Labour are implicated in the Third Way’s abandonment of full employment.

Hawke and Keating read the runes and knew John Howard’s influence in the Liberal Party would grow and decided to triangulate him into impotence by implementing a so called reform agenda.

NZ Labour of Thatchered Mrs Thatcher in the 80s.

Tony Blaire and Bill Clinton drew on antipodean precedents when they came to power.

Fantastic to have a blog on NZ.

NZ is a small place. We all know someone who knows someone.Those of us who are politically engaged and support MMT need to use our connections to get MMT a hearing in the Labour and Green and NZ First parties.

NZ Labour is currently bereft of ideas. They got elected without having any clear political philosophy or economic principles. The Greens were a bit better – but even they don’t get fiscal policy. NZ First at least had the guts to say capitalism in its current form was a failure.

They will preside most likely over the next recession and they need to realise that they need some ideas otherwise they will be electoral toast. They think monetary policy will save them. Good luck with that.

I wonder if Italy will finally get out of the EURO? It was a fascinating election to watch.

Below are the current ALP Values regarding “Responsible Fiscal Policy”

Dear Bill

It remains to be explained why Australia and NZ persistently run current-account deficits. You seem to regard it as a given, but it is not. Analysis of sectoral balances is totally valid, but it doesn’t tell us anything about the direction of causation.

Let’s assume that in a country the households don’t save anything, and that businesses are net borrowers. If the government also becomes a net borrower, then the current-account deficit will increase more. Is that desirable?

Regards. James

Dear Bill,

‘Voters have seen through all the neoliberal nonsense that they have been bombarded with over the last decades ‘

I really don’t think that this is demonstrably the case.

Basically, as Bill has pointed out many times, the Left failed to create a real narrative of what happened over the last 40 years. So the Left failed abysmally and that has led the voters to the inarticulate mumbling of the Right.

There is no sign that the voters have rejected neo-liberalism because neo-liberalism hasn’t been explained to them by the Right. Indeed, many of the Right (eg. UKIP in the UK) are dominated by highly financialised individuals who have pocketed a lot of wealth from the neo-liberal years and use the crisis to channel voters down a blind alley to be mugged again.

In the UK we’ve got a discussing throw back to the world of top-hatted toffs in the form of Rees-Mogg whose doing a sort of ‘Make Britain Great again’ version of Trump’s guff and plenty of people are falling for it whilst he screams about cutting the deficit and destroying welfare. The Tories have already been exploiting the tension between the in -work poor and benefit claimants ( who are supposedly all fraudulent, lazy, claimers despite the official ‘fraud’ statistic being 0.7%) and have made the ill/vulnerable jump through the most appalling and demeaning hoops often leading to severe stress and suicide and worsening health outcomes.

So, I don’t really think voters have ‘seen through’ anything at all; they have simply been led down a channel to suit the aspirations of another financials class offering a nice sprinkling of xenophobia and nostalgia whilst taking the piss.

Bill I agree I’d like to see both major parties annihilated in turn. The catch with doing away with Labor is there is no hint of a sensible party to take over, and very few outside the parties speaking sense – even old-fashioned Keynesianism which would be a lot better than the present mess.. The Greens ought to be, but they seem quite unwilling/unable to step up to the main game. The issues they champion are all well and good, but meanwhile the country is being hollowed out and turned into a police state at a rapid rate.

James

The national government is the source of the money it does not borrow from anybody it has the soveriegn priviledge of issuing the currency. That is the link you and 99 percent of the population do not see.

That is the point of this blog.

Dear Alan

You are right. I expressed myself poorly. I should have said that, if households don’t save anything at all and if businesses are net borrowers, then government deficits will increase the current-account deficit. You have to agree with that.

Cheers. James

Simon Cohen

Tuesday, March 6, 2018 at 20:09

I agree. The voters have seen through nothing. All they see is worsening inequality, stagnating wages and the decimation of public services and infrasructure. So they cannot vote for either of the main parties or hitherto dominant parties and look for some saviour who has the rhetoric. I am a great Italophile having spent a lot of my life in that lovely country, and I am interested to see who finishes up leading a coalition there – it is hard to call at the moment. But whoever it is, I’m afraid it will be business as usual as we saw with Syriza in Greece. There are forces out there much stronger that mere politics.

Re: New Zealand: New Zealander Brian Gould used to be a prominent Labour MP in Britain, but went back to NZ after “New Labour” came into the ascendant. I’m not sure if he became active in NZ politics after his return there. He’s mainly an academic and writer now, I believe. However, I know he is sympathetic to the ideas of MMT. One would hope he would be able to influence thinking in NZ in a positive way.

The problem with traditional Labour parties being destroyed is, as others have suggested, what is to fill the gap? The danger is, as we’ve seen, that the right moves into territory that really the left should be occupying and dominating.

In the UK, after the Lib Dems had thrown in their lot with the Tories in 2010 and Labour were still more or less Blairite, it was hard to know what to do. In the period leading up to the 2015 general election, it became clear that the Green Party were the only explicitly anti-austerity UK party, and many left-inclined people flocked to their cause in the so-called “Green Surge”. I was one of those.

However, I seem to find myself disagreeing with them more and more, not least of course, on the EU.

Corbyn’s Labour seemed to offer some hope, but unfortunately, there are still some unpleasant aspects to the way the UK Labour party does its politics. “Tribalism” is one way of summing it up. Plus we’ve been here before, some of us. In the 1980s, those of us who opposed nuclear weapons were told “well, it’s obvious you have to vote Labour”. Then Neil Kinnock reneged on his CND past and the Labour non-nuclear defence policy, in an attempt to become “electable”.

John McDonnell seems desperate for Labour to seem “electable” again with his silly budget rules.

So, sadly, it’s still not all that “obvious” that we “have to vote Labour”.

I think we have to take Bill at his word and “spread the word” to people of all parties and none, so that the truths that MMT makes clear are out there and so obvious that the leaders of whatever party will not get away with neoliberal lies to the voters.

Mike Ellwood,

‘So, sadly, it’s still not all that “obvious” that we “have to vote Labour”.’

I think Labour is the only option at present. Remember, there are many people suffering with poor or non-existent services, housing shortages of staggering proportions while developers rake in rentier profits; mentally ill suffering an outrageous deprivation of support and facilities; the ill having to perform exasperating acrobatics in order to get help.

yes, Labour are using post-Keynsian stuff about paying back the deficit later which is all nonsense, of course but AT LEAST they will increase it and alleviate the suffering which is substantial.

What do we do-keep the Tories in until Labour’s language framing is MMT compliant? I don’t think so-unless we use Lenin’s ‘The Worse the better’ approach which might have some merit-problem with that is people suffer and die in the meantime whilst the Right and its corporate money managers sweep up again.

When the suffering is as bad as this you need an incremental improvement. The deficit spend will itself lift the economy and could sweep away 40 years of bullshit when people realise that a deficit spend works!

“You have to agree with that.”

No we don’t.

Try again and ignore the country’s borders. Instead just have a government sector and a non-government sector holding the country’s denomination.

Once you do that you’ll find that it is all just savings. The non-government sector desires to save in the denomination. That’s it.

Exports of savings in the denomination is the cheapest product a nation can produce. So you treat it like any other export and work to avoid export monoculture.

There are two Philips here so I`ll switch to PhilipO

James Schipper,

Before I go further, James, are you making the assumption that since businesses are net borrowers, and households are neutral, investment is then positive leaving I>S ?

Mike Ellwood. Bryan Bill had a supporting article published in the Bay of Plenty (where he lives) newspaper – apparently it was published yesterday but I can’t find the link. Here is the text:

Our new government has made a confident start, and not least with one of its better ideas – a Provincial Growth Fund. We now know enough about this proposal to recognise just how valuable it will be, not just to the regions but to the whole country.

That it will deliver a boost to those parts of the country whose economy has been languishing cannot be doubted. The focus on communications and transport alone, with the special emphasis on rail, will help to bring more distant areas of the country back into the mainstream. And better rail communications will not only keep trucks off our roads but will bring benefit to enterprises such as the Port of Tauranga.

And it is not just output that will benefit. It will be local employment as well – and more jobs will provide a shot in the arm to local retailing, construction, and investment – a veritable virtuous circle.

And then there are the benefits to the environment that are clearly being targeted. Tree-planting on a large scale will boost forestry but will also help us to meet our greenhouse gas target. The shift in transport policy away from building more roads in favour of updating our rail network will do likewise, as well as reducing the road toll and opening up new development.

But those conditioned by years of being told that cutting government spending is the top priority will worry about the cost of these measures. Funding all these initiatives from one dedicated new fund is a good idea, but the money for the fund still has to come from somewhere, doesn’t it?

Well, not necessarily. You may be surprised to hear that the one thing that governments are never short of is money. Governments all around the world have been creating large quantities of new money for the past ten years or more. We don’t always recognise it as such because they have preferred to call it “quantitative easing”, but creating new money is what it is.

Quantitative easing, however, almost always had the limited one of providing money to the commercial banks so that, after the Global Financial Crisis, they could re-build their balance sheets. But new money created by governments does not need to be for that purpose alone – indeed, creating it to invest in the productive economy so as to produce an immediate return to the country as a whole makes a good deal more sense than just helping out the banks.

And that is what experience in earlier times and in other countries tells us. Many countries have in the past created new money to fund increases in output – whether it was President Roosevelt building American industrial capacity in preparation for entering the Second World War or Japan re-building its industry after its defeat in that same conflict (and Japan is doing so again today). And Britain rearmed in a hurry to withstand a Nazi invasion without worrying where the money would come from. What those countries realised was that it was ridiculous that the effort to increase output should be frustrated for the lack of money, when the government could create all the money that was needed.

Our own history offers us one of the most important instances of this being done. In the 1930s, in the middle of the Great Depression, the great Labour Prime Minister, Michael Joseph Savage, authorised the creation of new money so that thousands of new state houses could be built, thereby providing jobs for the unemployed and homes for the homeless and – incidentally – an income-producing asset for the government.

Money is after all primarily a facilitator or enabler; it makes no sense for governments that are ready to create new money for financial purposes to baulk at doing it for productive purposes if the need is there.

The great economist, John Maynard Keynes was very clear. If the banks can create new money every day for their own profit, why shouldn’t governments do likewise for the purpose of investing in our productive capacity? Creating money by the government cannot be inflationary, said Keynes, if it is matched by increased output – and isn’t that exactly what the Fund is designed to do and will achieve? Couldn’t it be even more effective with some real oomph behind it?

Bryan Gould

25 February 2018

To respect to the other Philip on this blog I will adopt the handle PhilipR.

James

If you think about the process of causation, an increase government spending over tax receipts cannot flow through into an 1:1 increase in imports over exports whilst nothing changes in the private sector.

Australian government spending cannot change foreigners’ propensity to buy Australian unless the Australian dollar appreciates in value to make Australian product more expensive on international markets. This will not happen because if you stimulate the Australian economy through government spending, you will create more imports into the country which will put downward pressure onto the Australian dollar’s value on the foreign exchanges.

So now you’re in a situation where the amount of additional imports generated by government spending has to be equal to 1:1 at the very least and probably has to equal more than that to compensate for the additional exports generated by a depreciating Australian dollar.

Do you really think the government would spend all of its extra G overseas? If there is a jobs guarantee in place, we know the additional spending will be at home. In the absence of a jobs guarantee, some of the extra government spending will be spent at home anyway.

The change in net exports will never equate to the increase in the government’s budget deficit. There is no reason why it should. Some of the additional government expenditure has to impact on private sector in the domestic economy.

currency

Now I’ve had a little time to think about it I will add that James’s suggestion that the change in net exports will equate to the increase in government spending can only hold true if the economy is at full employment.

Some of the extra G will be spent at home, and since the economy is at full employment that extra expenditure at home will reduce the pool of goods and services otherwise destined for export.

Since the economy is at full employment anyway, the extra expenditure will also have to be met by additional imports to accommodate it because a fully employed domestic economy simply cannot produce any more goods and services.

An economy that cannot produce any more will have to turn to the foreign sector to accommodate an increase in G.

Then again, no one is suggesting an increase in G if the economy is at full employment.

Unfortunately I suspect that only a tiny percentage of the Australian and New Zealand electorate are deficit owls -those that accept that the national government has the fiscal capacity to ensure full employment. Most are probably still deficit hawks. Many and perhaps most are however concerned with the neoliberal drift in their respective nations which is a very encouraging sign but as yet there are no parties that meet the definition of deficit owls on offer.

The Australian Greens are probably somewhere in between being deficit doves and deficit hawks as they have a fiscal policy of ongoing deficits of 3% of GDP which may sound promising but the current Australian federal deficit is about 2.4% of GDP and Roy Morgan Research estimate Australia’s current combined unemployment and underemployment rate at about 19.3% of the eligible work force.

http://www.roymorgan.com/morganpoll/unemployment/underemployment-estimates

Where did Chris Bowen get the 1% of GDP figure for the current deficit? Misquote or is he totally incompetent?

Winning over enough of the electorate to the merits of the MMT approach is probably a ‘bridge too far’ when the mainstream mass media and international capital are trying to do the opposite. Persuading key decision makers in the progressive and centre political parties should probably be the main focus.

Like Germany maybe Labor will join the Conservative Liberal and National Party Coalition to form a grand coalition neoliberal government at some point, so an effective progressive party is desperately needed as well.

Australia needs a proportional representation voting system like New Zealand to effectively break the stranglehold of the two party system that stubbornly remains neoliberal.

I think Bowen is right, though wrong, in not rocking the neo liberal boat. If he suddenly said MMT things the nastiness of opposition would be wondrous to behold. It might well lose Labor the election, the one the LNP seriously deserve to lose.

No, it needs to be disguised, enacted in a disguised way [which should not be too hard as its that way already] once in Government. We recall the flak that Rudd got for the stimulus during the GFC. Well, take the flak, results will turn it around over time. Then the LNP will be naked.

The trick is to get Bowen on board.

@Botticelli: Thank you for the Brian Gould quote! 🙂

Dear Philip

I’m not making any assumptions about the behavior of a particular sector. The only certainty is that the balances of the various sectors have to add up to zero. In some countries, businesses have now become net savers. If households are also net savers, then it is a good idea that the government runs deficits in order to absorb those savings. Otherwise they’ll have to go abroad.

The government simply should not tie its hands by aiming at balanced budgets all the time, but I think that it should also look at the current-account balance. If there is already a large current-account deficit, then increasing the government deficit may also increase the current-account deficit, although, as you pointed out, there won’t be 1 : 1 correspondence.

Many people don’t understand the balance of payments. In Canada, a lot of people think that it is good to have current-account surpluses, but they also think that it is desirable to have a surplus on the capital account. In other words, they want both the current account and the capital account to have a surplus.

Regards. JS