I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The comeback of conservative ideology

Today I have been writing about the resurgence of the conservative ideology. Some are even saying the crisis is over. Others are more circumspect and try to appear reasonable – “it is not the time to cut back yet but we need a transparent plan for fiscal retrenchment outlined”. That sort of argument. But there is an increasing number of contributions from past players who were in various ways at the forefront of the neo-liberal putsch. The challenge for progressives is to assemble a united front to combat this growing and strident conservative comeback. I see modern monetary theory (MMT) as a vehicle for that defence. Unfortunately, the progressives are so divided about almost everything that there is little chance of a common front emerging. More the fools us. Anyway, in this blog I wander over the Tasman to New Zealand to remind myself and all of us what the zealots are capable of.

Ever hear the term Ruthanasia? You should have because she is still at it berating us about the wrongs of fiscal policy and the need for radical reform. Ruth Richardson was New Zealand’s minister of finance from 1990-93.

In her own words (her CV)

During the remarkable reform era in New Zealand from the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s, Ruth established her reform reputation. As New Zealand’s Minister of Finance from 1990 – 1993 she was the principal architect of New Zealand’s second wave of reform, complementing the first wave of reforms initiated in the mid 1980s by New Zealand’s other well known Minister of Finance, Sir Roger Douglas.

As an historical episode “Ruthanasia” followed “Rogernomics” as increasingly radical reform programs that were inflicted on the New Zealand population from 1984 onwards – for the next few decades. In 1990, the conservatives took over the Labour Party (an oxymoron if there ever was one) under the banner of “The Decent Society”.

However, they set about building on the radical restructuring that the Labour Party had begun.

Imbued with the growing neo-liberalism (Thatcher, Reagan etc) the New Zealanders went further than most in privatising public enterprises; deregulating; extensive trade liberalisation; cutting public spending in crucial areas of welfare etc.

They drove unemployment up to very high levels and brought in the hated Employment Contracts Act (ECA), which trashed most employment protections and conditions that had emerged over the previous 50 or so years of bargaining. The legislation blatantly targetted unions and they have never regained any significant representative status since.

Anyway, Richardson was recently published in the UK Guardian (November 9, 2009) – and it is clear she is still lecturing us on the need for A new era of fiscal responsibility.

She told the UK that if it “fails to get public expenditure back to a sustainable level, and restore a low tax regime, it risks decades of stagnation”. Before I tell you she is not qualified to be giving us lectures like that, we might consider her argument.

She starts with the question:

Where did this fiscal crisis start?

Most certainly, it is not just a function of the credit crisis. Decades of political denial and then delusion were the mothers and fathers of this crisis.

So you realise she is in the camp that is now increasingly prosecuting the viewpoint that the crisis is really a fiscal crisis by which they mean – excessive budget deficits.

The danger in the recovery period that is emerging is that this viewpoint is getting a lot of airplay and “column inches” in newspapers all over the world.

Somehow, we are being asked to forget the excesses of the financial market institutions (investment banks etc) who were “entrusted” by neo-liberal government to “self regulate” and create a “free” and “wealthy” economy.

Pity the main players were corrupt and incompetent. Pity that their self-interest was not even remotely aligned to that of rest of us although they were able to successfully give the impression that it was and that allowed them further scope to undermine our welfare.

But this is being brushed aside by the conservatives who are now bearing down fully on the fiscal positions of our national governments.

Richardson says that we are all in denial at present, thinking that “public finances … [can} … stand the weight of huge and permanent transfers to a bloated, inefficient and unaccountable public sector.”

She says that “Britain is now on the brink – the worst fiscal miscreant in Europe – is sadly a predictable consequence of that political denial.”

Of-course, from a MMT perspective, the British government’s deficit is obviously too small as a percentage of GDP. This is evidenced by the fact that GDP growth has been negative for six quarters despite the national government systematically increasing its deficit. Clearly it has not increased it enough.

A fiscal lag of 6 quarters is highly unlikely and obviously impossible if they had have implemented direct public sector job creation. Ideology rather than good fiscal management practice has prevented them from doing that.

Richardson then says:

The myth was peddled that public expenditure could be lifted and taxes lowered, both made possible by sharing the dividends of growth. The party conference season demonstrated that such myths have been mugged by reality. It is time to push the fiscal reset button.

New Zealand had to do it in the late eighties and early nineties and offers some compelling lessons. The quality of public policy and the architecture of execution are everything, as leaders of courage seek to haul their countries back from the brink.

Well the dividends of growth only come when there is growth. And if the private sector is contracting faster than the public sector is expanding then you will go backwards in output terms irrespective of the size of the public deficit.

The art of fiscal management is to ensure that you match the leakages from the income-expenditure system. The UK Government has failed to do that. Most governments have but the only sense that the UK government is “fiscally miscreant” is that they have failed by a larger margin.

And as we will see below – the case of New Zealand in the late eighties and early nineties does indeed offer some compelling lessons – but not the ones that Richardson would have us learn.

She goes on to provide her list of fiscal “imperatives”:

– A fundamental re-examination of the role of the state in the economy and in society; how best to secure growth, innovation and a culture of wealth creation; and how best to foster personal opportunity and responsibility.

– A detailed roadmap to take public expenditures back to a sustainable level over a short- to medium-term period (three to five years).

– A broad, but low tax regime that advances the stated economic and social goals.

– A modern set of public expenditure tools and employment practices that allows performance to be maximised, measured and made accountable.

– A new architecture that involves ministers, officials, parliamentarians and the public having new roles in the quest for fiscal responsibility.

I agree we need as a matter of urgency a fundamental re-examination of the role of the state in the economy so that our governments resume their responsibilities for full employment and equity.

I want sovereign governments to focus on social objectives rather than becoming mindlessly obsessed with some dollar value of the deficit. You cannot maximise wealth unless all your available resources are working. As we will see, Richardson reduced the wealth of NZ overall during her period as Finance Minister.

The detailed roadmap for cutting expenditure claim just sends me to sleep. Another case of being in denial of the role that net public spending serves in meeting the leakages of the private sector. I covered this mainstream inconsistency in this blog – We are in trouble – squirrels are falling down holes

The tax regime should be broad and simple but whether taxes are low or high depends on the government’s assessment of how much purchasing power it wants the private sector to have, and, implicitly, the desired balance of public and private.

Richardson was instrumental in radically shifting the balance in NZ toward private and this had devastating consequences for the most disadvantaged. It also hasn’t proven to be a robust way of running the economy given that it has struggled ever since.

The other two imperatives are non sequiters. In New Zealand they involved ridiculous procedures being placed on government officials which just added to the bureaucracy and also the so-called creation of the independent central bank.

This placed significant power in the hands of the then governor Don Brash and had devastating consequences.

Prior to the mid-1990s, NZ Government had always considered true full employment to be among their primary responsibilities. In 1984, the Labour Party won government and like the Hawke-Keating Labor government in Australia during the same era abandoned these objectives and tried to prove they could mix it with the best of neo-liberals.

In NZ, they set about devastating the country (that “remarkable reform era”) and created a new industry – unemployment. The same thing though less severe occurred in Australia.

Unemployment became a policy tool (for disciplining inflation) rather than a primary policy target. The inflation-first monetary stance (and undemocratic reforms of the central bank) combined with a harsh fiscal policy contraction to drive up unemployment and significantly reduce per capita income.

Successive right-wing governments (which not only included the conservatives but also the Lange Labour Party government which started it all) used the concept of a “strategic deficit”. David Stockman, the budget director under President Reagan, was the person to coin this term which is taken to mean using a budget deficit as a “political weapon”.

The strategy was to hand out huge tax cuts to allegedly “incentivise” (the word that was used at the time) private entrepreneurs even though there has never been any convincing research evidence to suggest that there are major losses of activity arising from taxation.

The resulting deficits were then paraded as evidence of the need for dramatic public spending cut backs.

Successive New Zealand governments, first under Roger Douglas (Finance Minister) who handed out huge tax cuts then privatised the public enterprises to “get the budget back in shape”, and then the conservatives, under Richardson, used the Reagan ploy. I recall reading somewhere that Douglas said that he was somewhat dishonest by not telling the public that the privatisation was really an ideological preference and had nothing to do with generating revenue.

After all NZ is sovereign in its own currency and Douglas knew that.

Richardson pulled the same ploy in 1991 and severely cut welfare payments. She was also responsible for the rise in public housing rents that drove thousands into poverty. This article provides an interesting account of the policy changes. I was in New Zealand for a while during this period and got to know the Porirua area quite well. It is a low-income, public housing estate north of Wellington.

The article says:

Historically, state house rentals had been pegged at 25 percent of the tenant’s income. In the infamous “mother of all budgets,” brought down by right-wing Finance Minister Ruth Richardson in 1991, the National Party government announced that rents would be raised to their full market value …

Despite the fact that full market rents were due to be phased in over a four-year period, the market-driven strategy had an immediate and devastating impact. A 1994 HNZ report showed that state tenants had seen an increase of 54 percent in total rents in one year alone, while social welfare statistics for the same year revealed a ten-fold increase in those receiving the accommodation supplement. Again in 1994, the Ministry of Housing found between 20,000 and 30,000 households in “serious” housing need, with half of this total living in either inadequate conditions or paying more than half the household income in rent.

I recall (but cannot find the the source at the moment) that as the rents started rising, people were forced to abandon their housing and share houses on the Porirua estate. Richardson apparently observed the increasing rate of unoccupied public housing as being indicative of the people finding better commercially-available accommodation as a result of forcing market rates onto the public housing. It was an incredible observation in the true sense of the word.

Within the space of a decade, New Zealand had been transformed from a country that valued and pursued full employment into a country that allowed its government to generate and maintain high unemployment and increased poverty rates.

It was against this background that Alister Barry produced a 2002 movie The Land of Plenty, which examined the period that Richardson was Finance Minister and Don Brash was New Zealand Reserve Bank governor.

Barry noted that:

I was shocked, and so began to study in detail the theory and practice of what is called macroeconomics and the Reserve Bank’s monetary policies. Year zero turned out to be 1984 and the policy transformations bought on by finance minister Roger Douglas. What a profound betrayal that the New Zealand Labour Party should deliberately introduce a policy aimed at ensuring tens of thousands of workers were unemployed! Not only were they to be unemployed, but they were to be anxious and if necessary hungry, driven to search for work and in so doing maintain “downward pressure” on the wages of their fellow citizens.

Economists in the Reserve Bank and Treasury wrote papers about the effectiveness of things like “churn” in the ranks of the unemployed. The Labour Department and the Department of Social Welfare were transformed to support the new doctrine. The Employment Contracts Act of 1991 was seen as crucial to refining our new policy of permanent unemployment.

The movie is compelling and essential viewing and can be ordered from HERE – and the DVDs are very cheap.

You can also watch the movie in 8 parts via this link.

One of the narratives that I will never forget starts towards the end of Clip 5 (around 10.25) on the film home page above. It continues into Clip 6.

You see how devious the central bank and government collaborative activity was. They contracted a university nutrition department to provide them with minimum standards of nutrition.

You see how arrogant and junior Treasury officials were given the responsibility by Richardson to determine the “poverty line” upon which the benefits would be based. They discuss how they need to set the benefit level at a level where the unemployed person would have just the bare minimum nutrition. This would help motivate the unemployed worker to search harder for work.

You see how they contracted a researcher at Otago University in Dunedin to determine nutrition standards. They then duped the researcher by cutting the absolute minimum that the study had determined was necessary for basic survival by a further 20 per cent. This discounted “poverty level” was then called the NZ minimum income adequacy standard. They then set all welfare benefits at that level. You see the researcher admitting she was tricked by the Treasury officials and that the level they used was not going to provide basic nutrition.

The increasing poverty associated with falling welfare benefits and rising rents saw many New Zealanders being “forced to double up in primitive, unhealthy and overcrowded conditions. Many … living in basements and garages”.

There was also outbreaks of tuberculosis in “secondary schools in the working class suburbs of south Auckland, an area dominated by state rental housing” as well as other schools.

The film Land of Plenty reported that children in many of the poorer areas were diagnosed with rickets a disease arising from malnutrition and poverty, which was largely solved in the advanced world.

The radical reform agenda had severe negative consequences for the disadvantaged in New Zealand. The policies they introduced made New Zealanders considerably poorer.

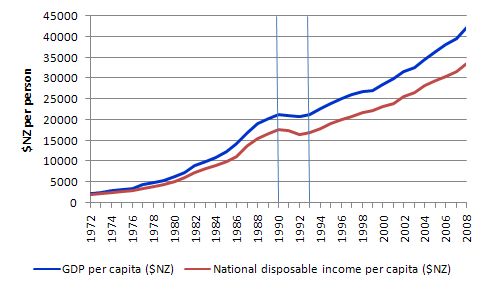

The first graph shows GDP per capita and National disposable income per capita (in $NZ) from 1972 to 2008. The vertical lines are the period Richardson ran the economy. It is not a pretty story.

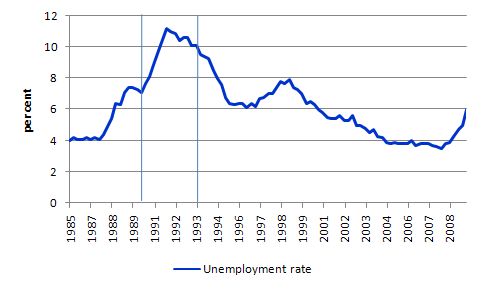

The next graph shows the NZ unemployment rate over the same period with the vertical lines again showing the period of her tenure as Finance Minister.

Part of the Ruthanasia story was the role played by the central bank. This is covered in some detail in the movie The Land of Plenty.

In an Scoop interview in the lead-up to the 2004 national election in New Zealand, Land of Plenty film-maker Alistair Barry offered these insights into the then conservative party leader (Don Brash) who had been the Central Bank governor during the Richardson years. The full interview is well worth reflecting on.

Scoop: Where would you place Don Brash in the political spectrum? …

Alister Barry: No he is an extremist, an idealist. Perhaps there is something in his personality that means he [Don Brash] finds it easy to imagine an ideal world.

In the case of when he was the Reserve Bank Governor and I’d say now as well, his ideal world is where the free market reigns supreme. He finds it easy to go out into the real world and try and transform that world into his idealised economic one – into that theory. In the film [‘ In a Land of Plenty’] the first time we see that is when he advocated the abolition of the minimum wage … A tendency to try and apply right-wing economic theory in as pure a form as possible, regardless of the social consequences.

This is the danger in the current period. The mainstream academy, humiliated by their failure to address the current financial crisis, are now starting to poke their heads up again. Shamelessly. While I would have wholesale sackings across Economics and Finance departments the mainstream is now reasserting their manic ideas.

Recall the blog – Islands in the sun – which discussed Robert E. Lucas among other things. His former co-author Leonard Rapping who later rejected the work and the approach said this:

… we were in the Chicago tradition, so we assumed perfect competition and profit and utility maximisation. Every single proposition had to be consistent with those assumptions. There were certain rules of logic that had to be followed, and the discussions were very tight and logical. We would try to explain everything in terms of the competitive equilibrium models. (We had learned that from Friedman)

I was also thinking about Real Business Cycle theory the other day and was remined of it again after listening to this Guardian Panel. At one point, one of the commentators who said that mainstream macroeconomics had become “horribly theoretical” because it was easier to get published (referees could more easily “judge whether the math is right”),

He went on to say that the RBC mainstreamers try to explain recessions as a “bunch of people who all want to take time off at the same time to pursue leisure”. I again recalled an article by Robert E. Lucas, one of the proponents of RBC which he wrote in 1980 as the theory was being propogated in academic journals and teaching classes. He said (in Methods and Problems in Business Cycle Theory, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 12, 696-715) wrote (page 696, then page 709):

One of the functions of theoretical economics is to provide fully articulated, artificial economic systems that can serve as laboratories in which policies that would be prohibitively expensive to experiment with in actual economies can be tested out at much lower cost.

… a number of economists have worked to develop what I prefer to call equilibrium models of businss cycles. There are models … in which prices and quantities are taken to always be in equilibrium. In these models, the concepts of excess demands and supplies play no observational role and are identified with no observed magnitudes … Our task as I see it … is to write a FORTRAN program that will accept specific economic policy rules as “input” and will generate as “output” statistics describing the operating characteristics of time series we care about, which are predicted to result from these policies.

The problem in New Zealand was that the zealots believed this stuff and used their own population as the laboratory with massive costs and very little to show for it by way of long-term restructuring, which was the mantra that they used to justify all the pain they inflicted.

Richardson and Brash were partners in this. Here is a snapshot from the movie Land of Plenty at their “heyday”.

Barry then commented on Brash’s connections when he was RBNZ governor. I think his response has interesting resonances in the current period with the way the finance industry and governments are interlocked:

No he doesn’t actually like ordinary people – I think he’s probably scared of ordinary people – most of our successful Prime Ministers have been concerned about ordinary people and felt for them. When Don Brash was Governor of the Reserve Bank it was very interesting because he knew his own people – that is financiers and those in the upper strata of society, and gave lots of speeches around the country explaining Reserve Bank policy to them.

He virtually never spoke to women or Maori who were of course the people who suffered from Reserve Bank policy. Neither did he ever speak to any group of workers – for example a trade union meeting … despite the fact that he spent most of the day sitting up there in the Reserve Bank building deciding how he was going to f**k with their brains. He was trying to create a level of fear, how was he going to control their behaviour. How was he going to stop them demanding wage increases – that is what he spent his day doing and yet he was never brave enough to meet with them.

The other interesting point that Barry made was how the RBNZ tried to manipulate the education system. He said:

… The Reserve Bank set up a chair of monetary policy at Victoria University where the employee’s wages are paid either partly or wholly by the Reserve Bank. The Reserve Bank published a text book on economics for journalism students – they created a videogame which was distributed free to secondary schools where students could play this game of keeping inflation down.

Brash also gave a controversial speech (Fifth Annual Hayek Memorial Lecture) in 1996 as Governor of the RBNZ to the extremist London group – Institute of Economic Affairs which features in the film The Land of Plenty. You can read it (if you have a strong stomach) on the RBNZ WWW site. It is covered in Clip 7 of the film Land of Plenty.

The Australian connection

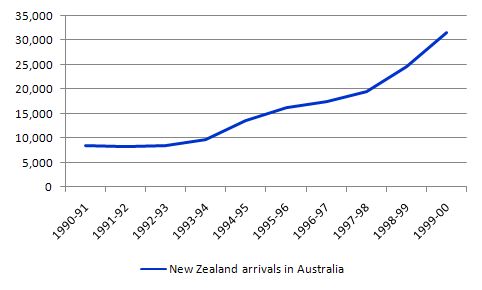

And you know what happened? Between 1990-91 and 1999-00, an index of arrivals from New Zealand to Australia rose from 100 to 379. The following graph shows the raw numbers. As the poverty spread the rate of growth in those choosing to leave for Australia rose very significantly (Source)

We were also undergoing our own neo-liberal nightmare but the institutional structure was harder to break down in Australia and many of the basic rights and conditions were maintained. Indeed, in 2007 we kicked the conservatives out because they finally were able to bring in a draconian industrial relations system that was similar to the ECA that had ravaged the New Zealand labour market.

So while things were not great here, they were much better than those that prevailed in New Zealand and this pulled the rising tide of Kiwis to our shores. The weather probably helped a bit too!

Conclusion

I sense a real fightback occurring among the conservatives at present and they are rapidly revising history. History has a way of being forgotten but is always a good thing to remember.

The experience of New Zealand during those years of being ruthanased by the free market zealots should serve as a warning to all of us. The current fightback may actually lead to a very significant backlash occuring.

That is enough for today.

I believe Marx once remarked: “History repeats itself; first as a tradgedy, second as a farce”.

I have noticed the exact same phenomenon you are referring to Bill. Increasingly, everywhere I look I see the most extrordinarily blatant arguments made by the champions of the system that brought us the GFC. Arguments that would seemingly have us believe that a poorly regulated financial sector was just an innocent party in all of this and that the real cause was government. Micheal Sutchbury appears to be arguing that it was all the fault of the US current account deficit.

And where is the “progressive” side’s counter argument? Nowhere it would appear. This neo-liberal horse shit is going more or less unchallenged. When the panic first set in late last year, I remember Mark Bahnisch of Larvatus Prodeo expressing doubts that this was the end of the neo-liberal paradigm because there was simply no broadly percieved alternative socio-economic narrative.

Perhaps things need to get a lot worse before people even begin to wonder about alternative possibilities. And with a competition brewing to see who can slash public spending in recessed, high unemployment economies the farthest, that may well be a distinct possibility within a few years.

I just stayed up late watching The Land of Plenty. Glad I did. It shows very clearly how unemployment was used as a weapon. It also underscores to me what a waste of space Labor Parties are. I think they are the enemy just as much as Conservative Parties. (Or nearly as bad. I’m annoyed at them after watching the film and am struggling to see any benefit to having them.) It also illustrated how illogical neoclassical economists can be. At one point they tried to eliminate the minimum wage, which would have brought the lowest wages closer to the benefit level, and then when they didn’t get their way on that, they turned around and called for welfare cuts to increase the gap between the lowest wages and the benefit level! Talk about internal inconsistency. Triumph of apologetics over science — like most neoclassical economics.

Regarding signs of a resurgence in conservative ideology, I think it is to be expected that capital and governments will try to use the crisis as an opportunity for further attacks on the living conditions of the general population if they can get away with it. Cutting back deficit expenditures could help them in that aim unless it induces people to push back, in which case the strategy could be playing with fire.

Neoliberal capitalism is based on the theory that capital goods are the main driver of prosperity in that they constitute the means of production that generate surplus value, especially since the proliferation of technology. Consequently, this thinking effectively denies that labor and land are co-factors. Labor and land are commoditized, as it were; at least slaves were regarded as capital assets. Now workers are fungible, and the environment is considered as expendable as workers. The objective of capital is keep all costs as low as possible in order to maximize capital formation as the way to “increase national prosperity,” which is equated solely with GDP.

The reason that unemployment is not targeted is because the theory holds that a sufficiently sizable stock of unemployed is needed for a competitive wage market, i.e., in order to undermine the bargaining power of labor. Moreover, now that labor is fungible globally, the race is on to the bottom. The global stock is far greater than any foreseeable need, given the rate of global capital formation.

What is the answer? Do the math. What is the opportunity cost relative to NAIRU of not running the economy at full productive capacity with full employment and stable prices by using MMT and a Job Guarantee?

But implementing this involves changing not only the current model but also the current paradigm, along with its conceptual framework and universe of discourse. For example, the “fiscal responsibility” meme has become the established narrative in that it is simple to understand on the bogus analogy of household finance.

Thus, this is not only an economic and political issue, but also a conceptual one. George Lakoff has addressed this in his political writings, such as The Political Mind, which advise progressives to use cognitive science in addition to economics and policy arguments, which all too often come across as wonky and go over people heads. This is a problem that Democrats face in the US, where they are outmaneuvered by simplistic and erroneous conservative sloganeering.

Of course, it’s necessary to have a sound basis for one argument, that that’s only a necessary condition for success in governing, not a sufficient one for getting elected or changing policy. While Stock-flow consistent macro models is a brilliant summary for those able to think it through, everyone can grok A simple business card economy pretty much right off.

This was a bit helpful, but not very as i am only 14 years old, and i need this information for sos. thank you anyways. Your language, a 6 year old should be able to understand, not a person who has just got a degree in intellegent words. okay. sorry for taking up your time.

There are two other excellent documentaries you can watch on youtube which cover the same period of New Zealand’s history: Revolution and Someone Else’s Country.

Revolution is particularly interesting because it features very candid interviews with David Lange and Roger Douglas. Douglas comes across as a very intelligent person completely lacking in empathy and any sense of democratic accountability, who knew exactly how to manipulate various crises to launch his radical right-wing program. Lange just comes across as a weak, easily manipulated windbag.

Jim Bolger and Ruth Richardson appear in the documentary to be almost identical to Lange and Douglas, although Jim Bolger was decidedly worse than Lange because he actually really believed in the Employment Contracts Act. The fact that he now tries to condemn neoliberalism and actually said that unions have become too small is the absolute height of hypocrisy.