I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A voice from the past – budget deficits are neither good nor bad

The International Labour Organization (ILO) released its Global Employment Trends for Youth 2012 report today (May 22, 2012). It is harrowing reading and I will consider it later in the week. It tells us that youth unemployment is rising and will be unlikely to see any improvement until at least 2016. The ILO recommend a raft of government initiatives which would require budget deficits to expand. But, of-course, the dominant political narrative is to cut deficits in the false belief that this will engender growth. Exactly the opposite is happening and for good reason. I came across an article from 1982 today which tells us why austerity is dangerous and damaging. It also conditions us to understand that budget deficits are neither good nor bad but policy choices can be.

I am cleaning out my office at present – and discovering all sorts of jewels (articles) that I have collected. In this digital age, piles of paper which attract silverfish are no longer necessary. The particular article I found today to be interesting was written by US economist Gardner Ackley in 1982 and published in the November-December issue of Challenge.

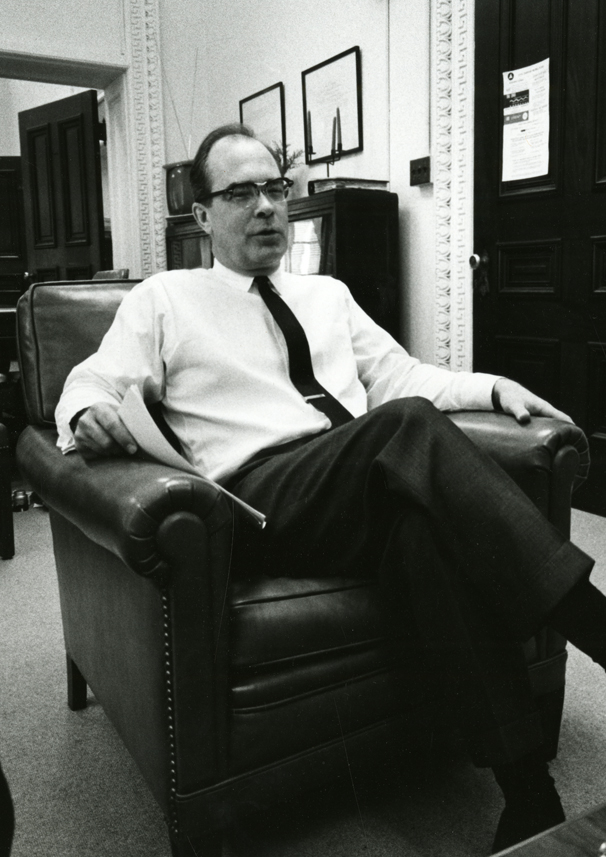

Here he is in the days when university offices were comfortable and you read things on paper rather than computer screens.

Ackley died in 1998. His 1961 textbook – Macroeconomic Theory – remains one of the better “Keynesian texts” of its day. His alma mater, the University of Michigan Notes that:

Ackley became a key proponent of the Keynesian idea that government must use fiscal and monetary policies to “fine-tune” capitalist economies. John F. Kennedy appointed him to the President’s Council of Economic Advisors in 1961; then, as chairman of the Council from 1964 to 1968, Ackley advised President Lyndon Johnson that the war in Vietnam and the domestic programs of the Great Society could not be sustained without tax increases. Johnson’s failure to heed Ackley’s warning has been credited with the crippling inflation of the 1970s.

They quote him as saying:

I had a general resentment against the [Great] Depression, and felt there must be a way, and that economics must be it.

This is the sort of sentiment that motivated me to study economics, when I was also interested in Anthropology, Mathematics, Music, History, Philosophy and Political Science.

The Challenge article – You Can’t Balance The Budget By Amendment – (link is active via JSTOR if you have access was written at the time the US House of Representatives were debating a proposed Constitutional Amendment requiring a balanced federal budget. Sounds familiar, eh?

There have been regular attempts in the US to push through amendments of this kind. So far all have failed. The 1982 effort passed the US Senate (by a vote of 69 to 31) on August 4, 1982, but was foiled in the US House of Representatives (with a vote of 236 for to 187 against) on October 1, 1982. See Senate Report 105-003 – for more detail. Constitional amendments require a 3/4 majority from both houses.

Gardner Ackley was opposed to such an amendement and said:

The proposed Constitutional Amendment to restrict both federal government deficits and the level of federal government expenditures relative to national income lacks economic or political justification. Its enactment, I believe, would severely damage the ability of the federal government effectively to carry out its responsibilities, and could significantly reduce the welfare of the American people.

The conclusion is as valid today as it was then.

Fiscal policy has to be flexible – expanding and contracting its influence on the economy as the spending patterns of the non-government sector relative to real productive capacity require.

Gardner Ackley made another point that bears on this debate – that the push to limit government:

… implies that our representative system cannot be trusted to make intelligent choices in budgetary matters. If this is the case for taxes and spending, can we trust it for questions involving social relations, education, foreign affairs. and civil rights?

Clearly groups who oppose all government involvement would say yes – they do not trust government at all. But even at this extreme end of the debate the argument falters because the government has to issue a currency. That capacity, in turn, can be severely restricted but with consequences for the currency users.

For example, the Eurozone is a form of restriction on currency sovereignty. And it is this very restriction that has guaranteed that the negative demand shock the Eurozone received in the 2007 has morphed into a major economic crisis there in 2012. It is the blind adherence to fiscal rules (the Stability and Growth Pact soon to be the Fiscal Compact) that has ensured their crisis worsened.

Compare the Eurozone situation to that of the US or more recently Japan.

But whichever way you lean, a government is central to the monetary system and so it is better to argue for ways to ensure the government acts in our interests in terms of its use of its currency-issuing capacities rather than to tie it down so that it cannot act in the public interest.

Further, as Gardner Ackley hints, we trust governments to resource armies and attack other nations. Conservatives applaud this side of government activity, not the least because, their private companies make fortunes servicing the military machines. But when it comes to assisting the most disadvantaged and to provide them with pittances in the form of income support, the conservatives claim that such payments undermine incentive and enterprise.

After describing the specific 1982 proposal, Gardner Ackley proceeds to analyse how deficits and the economy interact. He said:

My own position on deficits has always been, and remains, that deficits, per se, are neither good nor bad. There are times when they are not only apppropriate but even highly desirable, and there are times when they are inappropriate and dangerous. During a recession or a period of “stagflation”, deficits are nearly unavoidable, and are likely to be constructive rather than harmful.

He listed the recessions that he was familiar with (1954, 1960, 1970-71, 1975, 1981-82) and concluded that imposing fiscal austerity during those times “would be prohibitively costly – in jobs, production and real incomes – and perhaps even impossible to achieve on any terms”.

Note he is relating the budget outcome to the circumstances in the economy not to some pre-conceived notion that some balance is desirable and another is not.

The reference to a program of fiscal austerity being “impossible to achieve on any terms” is also important. Please read my blogs – Structural deficits – the great con job! and Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – for more discussion on this point.

The government budget balance is the difference between total revenue and total outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It should be appreciated however that movements in the final budget balance do not provide a reliable indication of the intent of the government.

We cannot conclude that if the budget is in surplus then the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit then the fiscal impact is expansionary (adding net spending).

This uncertainty arises because there are so-called automatic stabilisers operating as a result of swings in economic activity, which are, in part, influenced by the discretionary shifts in government fiscal policy.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary in a pro-cyclical manner over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind.

The point that Gardner Ackley is making is true today as well. Governments that impose fiscal austerity with the sole aim of reducing their budget outcome (and related public debt aggregates) may cause economic growth to falter which in turn undermines their tax revenue.

The upshot is that the budget balance moves further into deficit or doesn’t move into surplus as planned which then triggers further mindless cutting of net spending. The reaction of the Australian government at present is a case in point. The federal government is obsessed with achieving a fiscal surplus next financial year and in the face of a slowing economy with declining tax revenue its response recently was that they would have cut spending even harder.

Gardner Ackley would consider this fiscal conduct to be totally inappropriate and dangerous. It remains so today!

He also notes that:

… large deficits in a period of substantially expanding output and employment are dangerous and damaging. They can easily produce excess demand, over-full employment, and escalating inflation.

In this vein, he criticised Lyndon Johnson for running excessive deficits in 1966 and 1967.

Note that he doesn’t say that when the economy is expanding the budget should be in surplus. He relates “large deficits” in terms of “excess demand”. At full employment, it is entirely possible (and likely) that the budget will still be in deficit (given the propensity of the non-government sector to save).

The point is that we have to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the budget balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

This decomposition provides (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical budget balances. The budget components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the budget balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the budget is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual budget outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the budget into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual budget outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical budget outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential output level.

The point is that structural budget balance has to be sufficient to ensure there is full employment. The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a budget surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the budget outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The budget will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

In this context, Gardner Ackley wrote that:

Some deficits are good; some are bad. Prohibiting them, or make them more difficult, not only limits the ability of the government to stabilize the economy, but can be positively destabilizing.

He also discusses the correlation between rising budget deficits and poor economic performance as one reason why proponents of balanced budget amendments thinks that “deficits are response for our poor economic performance”.

He says that “that hypothesis has been strongly expressed by President Reagan, by many members of Congress, and by many leaders in the private sector”.

Recall the Wall Street Journal article by Robert Barro recently (May 9, 2012) – Stimulus Spending Keeps Failing – which tried to argue exactly that.

Gardner Ackley wrote on this correlation:

Unfortunately, such “post-hoc, propter-hoc” reasoning is – as is often the case – basically erroneous.

It is much closer to the truth – although still far from the whole truth – to say that the main causal relationship between deficits and the sate of the economy runs in exactly the opposite direction: a weak and poorly functioning economy is responsible for most budget deficits.

In the current debate the commentators have become fixated on the rising budget balances rather than the underlying causes – the rise in unemployment.

If they pursued the latter with as much urgency and vehemence as they pursue the former, then their concerns would soon evaporate. However, by exercising their obsession about the budget balance – as an end in itself – they pressure governments to introduce pro-cyclical fiscal shifts (austerity) which not only ensure that unemployment rises but also almost guarantees their primary target will also move further away from their goals.

As a parting note, Gardner Ackley also recounted how a “substantial majority of American economists oppose such a limitation” (the balanced budget amendment).

He wrote:

No one can speak for the economics profession. It is nevertheless my sincere belief that, by a substantial majority, those who have received advanced degrees in economics, and who “practice” that subject in teaching, research, or similar professional capacities – and particularly those whose principle interest is in “macroeconomics” and/or “economic policy” – oppose enactment of a Constitutional Amendment prohibiting or limiting federal deficits.

30 years is a relatively short-time, but in the period since Gardner Ackley wrote that article, my profession has become seduced by the neo-liberal paradigm and the New Keynesian models have become dominant. I think if Gardner Ackley took his poll now he would be horrified to find that a majority supported such prohibitions.

Just look at what is happening in Europe at present.

The reality is that nothing substantive has occurred to show that the macroeconomics that Gardner Ackley espoused is deficient or wrong in terms of its depiction of the way the spending system operates in conjunction with the monetary system.

There are points of departure between Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and the macroeconomics proposed by Gardner Ackley but the differences are minor relative to the yawning gap between these views today and those held by the dominant paradigm.

The rise of this dominant group in my profession reflects shifting ideology rather than any substantive and credible attack on the economics of Gardner Ackley.

In terms of all the myths supporting the attacks on government net spending I thought this YouTube talk – by a US venture capitalist – one Nick Hanauer – was interesting.

The talk raised some media interest – see Time article (May 18, 2012) – Was Nick Hanauer’s TED Talk on Income Inequality Too Rich for Rich People? and this rather critical article in Dissent (May 21, 2012) – The Politics of TED.

The points that Nick Hanauer makes are sound. Whether he supports progressive movements or not is a separate issue.

Conclusion

It seems almost impossible for people to understand the point that budget deficits are neither good nor bad but policy choices can be. That is a basic proposition in MMT.

Governments should not aim for specific budget outcomes but rather, should aim to achieve full employment and price stability. At that point, the recorded budget outcome will be unambiguously good.

But by obsessing about the budget balance in isolation and setting up all sorts of rules and traps for governments the mainstream not only create bad outcomes but pursue bad policy. They are usually still left with deficits and rising debt – both are bad – in that context.

That is enough for today!

Correction: To amend the US Constitution, a 2/3rds majority of each house and then 3/4 of the state legislatures. (ref US Constitution, Article 5 Section 1)

Apparently the attack on Nick Hanauer’s TED Talk was lauched pre-release by the conservative mouthpice, National Journal. I personally found the talk rather mild compared to some other presentations of his theme (Nick himself expressed a similar assessment), and so I guess we can conclude that no dissent is to be tollerated from the conservative austerity meme, and that Nick himself is now viewed as a “traitor to his class”. Unfortunately for the National Journal, their attack seems to have generated a greater level of interest than Nick’s talk might otherwise have enjoyed. Such go the plans of mice and men.

As for Ackley, a quick scan of his other offerings shows, besides a keen interest in inflation, a belief in the intergenerational transfer of wealth. I guess this tags him as a full Keynesian as opposed to a pre-MMTer. Alas, Bill, he did not have the benefit of your instruction. 🙂

Another very interesting piece! Your blog is very much appreciated.

I hadn’t seen Nick Hanauer’s speech before so that was interesting as well. I’m from Finland and we recently had a trade union confederation boss criticise the idea of taxing the rich more because “the rich are job creators”. It just happens that I’m a member of one of the unions that his confederation represents. I’m planning on writing to him about economics and I’ll make sure to attach the link Hanauer’s speech to my message.

Benedict: Curious what you mean about Ackley & intergenerational, didn’t notice anything like that in my quick scan. Intergenerational transfers are of course possible, just not ones involving time travel, the scaremongers main merchandise.

OGS: a trade union confederation boss criticise the idea of taxing the rich more because “the rich are job creators”. Wow. What an achievement of propaganda. Trade unionists worldwide are turning in their graves. Does he think the jobcreators ever criticise the idea of taxing the poor in order to maintain the value of the government’s payments of welfare-to-the-jobcreators? I guess when Chico Jobcreator asks him “Well, who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes?” – he politely answers, “You”.

It seems almost impossible for people to understand the point that budget deficits are neither good nor bad but policy choices can be. That is a basic proposition in MMT.

This is the point I have tried to bang away on in my writing on MMT. It really is hard for people to grasp since monetarily sovereign governments are unique in comparison to other economic units.

Every economic unit except a monetarily sovereign government is stock constrained. It can only spend in excess of it receipts by drawing down its net stock of financial assets, either by spending some of the stock directly, or by issuing a debt claim against that stock. Once the claims against the stock exceed the size of the stock, the unit is insolvent, and can only continue to spend if others are willing to accept its IOUs even in the face of apparent insolvency, granting credit.

For a government like the government of Australia, the US, Japan or Canada, the whole notion that the government possesses a fixed “stock” of financial assets is a bookkeeping fiction. And if one insists on preserving that fiction and referring to the government’s asset stock, one one might as well view that government as having an infinite stock. Flows into that bottomless stock do not change the quantity of assets; nor do payments out of the stock change the quantity. Debt claims against that stock do not push the government closer to insolvency, because there is no bottom. The government is not stock constrained; it is only policy constrained.

The chief policy constraints are price stability and full employment. The government’s concerns are not with what happens to its infinite financial asset stock, which is a bookkeeping fiction, but only with the way in which flows into the government’s infinite well or out of the government’s infinite well affect policy aims in the non-governmental sector.

Also, debt is a legally binding promise to pay, and so all of these non-governmental units are bond by laws to their debts, laws that the unit itself does not control. But governments make the laws under which they, themselves operate, and if the makers of the laws – in the case of a democracy the sovereign people – find the laws onerous, they can change the laws.

Good or bad? Apparently it’s bad, and government is predisposed to profligacy ….

http://www.businessspectator.com.au/bs.nsf/Article/austerity-debate-economic-debt-IMF-deficit-bias-pd20120522-UHVWU?opendocument&src=idp&emcontent_asx_financial-markets&utm_source=exact&utm_medium=email&utm_content=43324&utm_campaign=kgb&modapt=commentary&WELCOME=AUTHENTICATED%20REMEMBER

From, you might have guessed, IMF.