In an early blog post - Inflation targeting spells bad fiscal policy (October 15, 2009)…

MMT predicts well – Groupthink in action

This blog will be a bit different from my normal fare. It provides insights into how entrenched a destructive and mindless neo-liberal Groupthink pervades the economics profession. For the last several years I have been on the ‘expert’ panel for the Fairfax press Annual Economic Survey. Essentially, this assembles a group of well-known economists in Australia from the market, academic and institutional (for example, union) sectors and we wax lyrical about what we expect will happen in the year ahead. To be fair, there is a large element of chance in the exercise as there is in all forecasting. So I am never one to criticise when an organisation such as the IMF or the OECD or some bank economist gets a forecast wrong. The future is uncertain and we have no formal grounds for even forming probabilistic estimates, given we cannot even assemble a probability density function (an distributional ordering of all possible events ) to extract these probabilities. So guess work is guess work and you have to be guided by experience and an understanding of how the system operates and the elements within the relevant system interact. What I do rail against is the phenomenon of systematic bias in forecast errors. For example, the IMF always predicts stronger growth than occurs when it is advocating imposing austerity (thereby underestimating the costs of the policy). The systematic bias in their errors is traceable to the flawed models they use to generate the predictions, which, in turn, reflect their ideological slant against government deficits and in favour of fiscal surpluses (as a benchmark). As luck would have it, in the 2016 round of the Fairfax Scope survey, I was fortunate enough to achieve the status of Forecaster of the Year (shared with 2 other members of the panel) – see Scope 2017 economic survey: Stephen Anthony, Bill Mitchell; and Renee Fry-McKibbin tie for forecaster of the year – for detail. I tweeted over the weekend that as a result “MMT predicts well”. There was a lot underlying that three-word Tweet and it intersected with recent events that demonstrate how far gone mainstream macroeconomics is – it is in an advanced state of denial and has lost almost all traction on the real world.

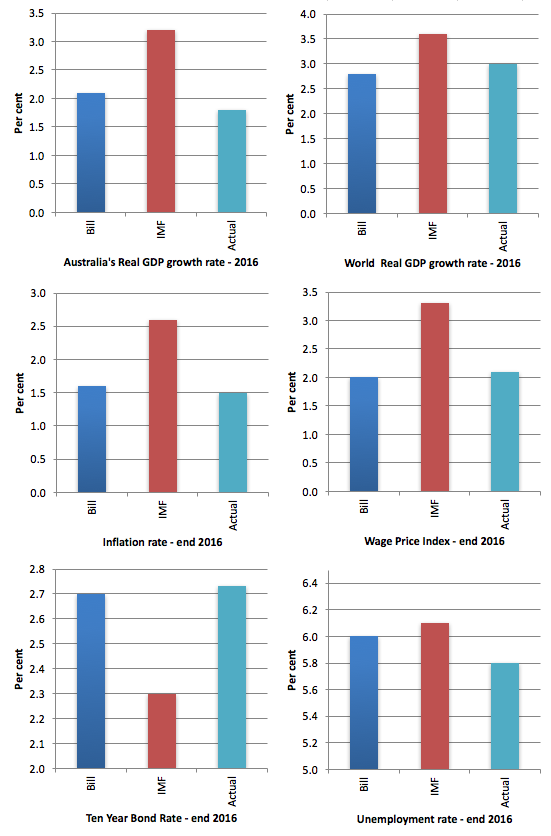

The following graph provides a selection of forecasts (for the indicators I get could more or less comparable results) for the year-ending 2016.

The blue columns are my Fairfax forecasts (provided in early 2016), the red columns are the IMF’s forecasts (the last they made towards the end of 2015 – so not much different information to the set I was exposed to) and the jade is the actual outcome (note the actual real GDP estimate is at September-quarter 2016).

It is clear on several key macroeconomic aggregates, that the IMF approach, which reflects a sort of industry standard among mainstream macroeconomists – is way off the mark.

I could show you earlier years with similar results. The errors that result from the mainstream models that the IMF uses are typically systematic.

They are usually way too optimistic when they are recommending fiscal cutbacks and way to pessimistic when a government is expanding its fiscal position to stimulate economies.

It usually overestimates wage inflation (because its Phillips curve approach is crippled by the flawed NAIRU concept) and it rarely goes close in guessing government bond market outcomes (because it relies on a flawed understanding of how nations with their own currencies operate).

The IMF approach based on its New Keynesian general equilibrium bias. It uses a number of formal models to generate forecasts which embed the standard mainstream components – micro-founded optimisation; rational expectations, long-run steady-state neutrality.

In February 2014, the Independent Evaluation Office of the IMF published an interesting analysis (BP/14/03) of “how the IMF produces forecasts for use in the World Economic Outlook (WEO) and Article IV consultations” – The IMF/WEO Forecast Process.

The IMF relies on its so-called Global Projection Model (GPM) , as the basis of its World Economic Outlook forecasting updates.

It uses “insights from micro-founded DSGE models” (calibrated Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models) based on attempts to aggregate rational, maximising micro behaviour into a representative agent macro but realise that they are “far from being able to integrate such models into a global model at this stage of the development of macro model building” and so they supplement it with the ad hoc use of time series or VAR models (VAR = Vector Autoregressive – no theory just data fitting).

They claim this means their approach:

… falls between fully micro-founded estimated models and purely time series or VAR models … On the one hand, it avoids one of the problems of many fully-estimated macro econo- metric models-unrealistic simulation properties because of difficulties in dealing with simul- taneity problems. On the other hand, by using economic theory as the basis for the model, the approach should be able to outperform global VAR models in forecasting and enable researchers to undertake policy simulations that cannot be addressed by VAR models.

Which you should read as saying that:

1. The so-called micro founded DGSE models are highly simplified mathematical expressions of optimal decision making in an environment of rational expectations (everyone knows everything to infinity with zero average forecasting errors) and free markets.

2. They create a macro universe by claiming that individuals are all alike (representative agent) and firms are all alike (representative firms) etc because they cannot solve the aggregation problem inherent in trying to move from individual to aggregate analysis – so they assume it away and assume the macro is just like the individual – so all errors inherent in the fallacy of compositions prevail and are ignored.

3. They cannot say anything about the real world with this approach so they then tack on ad hoc time series properties (lags in relationships, responses etc) which allow them to sort of fit data points.

4. But in adding these ‘real world’ elements, the properties (micro-foundations) they claim to be superior and which they laud over other approaches to assert authority, are completely lost. The actual behaviour of the model simulations etc are no longer driven by the pure optimising properties (which really just assert some theoretical long-run neutrality).

Some of that terminology will be difficult for many readers and I apologise. I just don’t want to write another blog detailing all these concepts.

The point is they think:

1. There is a long-run state where the path of aggregate spending is irrelevant. So fiscal policy cannot change where the economy reaches at some point in the future. They can derive mathematical expressions of that that they impose on the way the model adjusts to a shock (an introduced change).

2. The ad hoc elements (that have nothing to do with optimisation theory) allow the model to have ‘short-run’ dynamics that are different to this long-run, but the adjustment paths always head back to the long-run position.

There is no theoretical authority in this approach. It reflects an ideological position (the way the DSGE model is designed and calibrated) coupled with a crude, data-fitting approach in the short-run.

In general, to fit the real world data, they just make stuff up (residual adjustments – for example – where they just add things to errors to get a closer fit etc).

Please read my blog – When mainstream economists jump the shark and lose it completely – and the links to earlier blogs, for more discussion on this point.

It was in that sense, that I tweeted that ‘MMT predicts well’. In fact, MMT economists have an excellent track record in extrapolating the likely consequences of policy shifts and external shocks.

I invite readers who care to invest the time to go back through my blog where at key points in the last decade I have made statements that are in defiance of the sort of conclusions that the mainstream economists have made – and you will see who was wrong.

I should add that in previous years, Steve Keen has won the Forecaster of the Year title and I have been close. Both academic economists who deploy a non-standard approach heavily influenced by the development of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), although Steve and I focus on different things in our respective academic work.

Think about Japan! The New Keynesians such as Paul Krugman and the more free market mainstream economists (such as hang out at the University of Chicago) predicted terrible things for that nation in the 1990s.

We were led to believe it would inflate badly (because of the growth in the money supply), that the government would run out of money (because bond markets would stop buying debt as the debt level and ratio built up); and that interest rates would go through the roof (because the fiscal deficit was so large).

Result:

1. Low inflation bordering on deflation since the early 1990s.

2. Rising debt ratio – high bid-to-cover ratios in bond auctions – low long-term bond yields (now negative out to 10 years).

3. Rising deficits – but zero or low interest rates since the early 1990s.

4. Relatively low unemployment rates despite a massive property collapse and some natural disasters.

5. The sky above the Japanese islands remains firmly above!

The same goes for the GFC.

As government deficits rose and interest rates fell, notable mainstream economists came out and said that governments would run out of money as bond markets refused to buy debt; that inflation would accelerate and become hyperinflation, that central banks would have to hike interest rates to unprecendent levels to control the inflation as a result of the build up of assets on their balance sheets (expansion of reserves), etc etc.

The MMT economists all were calm.

Nothing along the lines that the mainstream approach predicted happened – they were not even close.

The neo-liberal Groupthink that has rendered mainstream macroeconomics moribund and irrelevant

Which brings me to the next part of the story – the devastating neo-liberal Groupthink that has infiltrated my profession and made it almost irrelevant to any person seeking knowledge.

We talk a lot about ‘fake news’ these days. Well mainstream macroeconomics as taught in universities and practices in international organisations such as the OECD and the IMF and within treasury and central bank departments – is fake knowledge.

Geographers and navigators moved on from their false ‘flat earth’ beliefs once they started to gain an understanding of the way planets form and the physics that govern their relationships and the empirical evidence that emerges from that understanding.

The Flat Earth theorists were beguiled by ships disappearing over the horizon onto to return intact.

Please read my blogs – Flat Earth theory returns – budget aftermath and Flat earth theorists – dumb but sneaky – for more discussion on this point.

The empirical reality of Japan, for example, should be the ships off the horizon wake up point for mainstream macroeconomics.

It should then prompt them to acquire a thorough understanding of the way modern monetary systems operate and the dynamics that govern the relationships between government and non-government.

They would then be able to reconcile the overwhelming empirical evidence that supports from that theoretical understanding.

In the Fairfax report on the Forecaster of the Year (cited above) the journalist noted that my forecast was:

… the closest on record-low wage growth, picking an ultra low 2 per cent, close to the 1.9 per cent recorded in the year to September.

So not only was my forecast an outlier but it was almost exact. I told the journalist that my forecast:

… would have been obvious to anyone who wasn’t seduced by the fairly steady unemployment rate. Underemployment had been climbing, tens of thousands of people had left the workforce who would have once been in it, and what jobs growth there was had been concentrated in part-time jobs that were typically non-unionised where workers had low bargaining power. This year he is predicting wage growth of 1.8 per cent, less than the rate of inflation, meaning earning power will shrink.

The mainstream macroeconomists barely have unemployment in their models – they think it is a voluntary, optimising choice that workers make not to work some times.

Their models do not consider underemployment or the casualisation of the labour market – those real world events are below their DSGE radar.

As a consequence they haven’t a chance of really forecasting these outcomes very accurately (on a regular basis).

The Fairfax article also said that my forecast:

… hit the bullseye on the 10-year bond rate, picking 2.7 per cent, which is where it ended up … [and] … He says the low bond rate was also obvious, given auction data showing queues of traders wanting to buy risk-free assets. For all the talk about the need to attract foreign capital, Australia’s government finds it pretty easy.

If you think that governments can run out of money, you will never really be able to understand the dynamics of bond rates.

Remember all the articles that poured out from mainstream economists in the early days of the GFC predicting sky-rocketing bond yields and governments being crippled by lack of ‘money’?

It was never going to be true but those underlying beliefs cause forecasts to be systematically wrong.

Which brings me to share another personal experience which builds on the recent critique by a UNSW economist of MMT. It was a ridiculous critique – which included libellous claims that MMT economists were cranks, charlatans, snake oil salespersons and the rest of it.

It set up some false straw person challenge to make us look like idiots:

So here’s my challenge to the modern monetary theory crowd. Please state a formal, precise, economic model in which a monetary authority can extract an infinite amount of real resources through seigniorage. Or be quiet.

Of course, no MMT academic has ever claimed that “a monetary authority can extract an infinite amount of real resources through seigniorage”. Read never.

That was a fake claim about us – an untruth, designed to degrade our academic reputation and justify the use of the libellous descriptors.

But it tells you about the state of mainstream macroeconomics.

Here is another interesting example.

Our new MMT textbook will be published later this year by the leading textbook publishers Macmillan Palgrave.

It will offer a two-semester sequence in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) from the introduction to the second-year (intermediate) level study. It is built on the introductory book we released earlier last year.

It is much improved on that book and covers a lot more material with some very sophisticated analysis (including the use of mathematics) and topical debates.

But it is faithful to MMT and is very graduated. We do not include anything formal (mathematical) for its own sake. A person with no background in economics will be able to make excellent progress as he/she traverses the 27 chapters in the book.

They will end up with an excellent understanding of the way the monetary system actually operates and appreciate the policy choices available to government and their likely consequences.

We have been through a rather exhaustive process before the publisher issued us with the publishing contract. It is not easy getting such a contract in this sort of market.

Part of that process involves the publisher inviting blind (to us) referees to review our proposal with sample draft chapters. This gives the publisher some idea of the market opportunities, who will take up the book for teaching purposes etc and provides us with feedback from the profession.

We received several reports from the publisher some which were obviously from heterodox economists who were all uniformly positive although the comments were not necessarily all favourable and some of the suggestions for clarification were excellent.

They were in the spirit of open debate – yes, the approach was sound (heterodox, MMT) but this or that could be improved etc.

Several other reports were from mainstream macroeconomists and they were all uniformly antagonistic.

It was clear from reading those reports that our approach offends the basic Groupthink ideology that the mainstream economists adhere to, which provides them with internal succour but renders their capacity to analyse the real world as being close to zero.

The textbook does not consider in any detail theories of unemployment that are built on the optimisation view that unemployment is a choice individuals make between labour and leisure and when the real wage they face is too low, they choose leisure because it delivers maximum utility.’

If that view was correct, then quit rates would be pro-cyclical. In the real world they are firmly counter-cyclical indicating people do not quit jobs at increasing rates when unemployment rises. Quite the opposite.

Why would we include an arcane neo-liberal notion which seeks to deny the involuntary nature of unemployment?

A standard mainstream response is that our general approach is old hat and out of touch with the way that modern macroeconomics is now taught. The mainstream textbooks all conform to the approach that macroeconomic reasoning begins with microeconomics (optimising markets and individuals with rational expectations, etc) and that DSGE modelling is at the core supplemented with time series calibration (as in the IMF approach outlined above).

Apparently, if a textbook does not take that approach they are killing the career prospects of their students in graduate programs, even though hardly anyone goes on to undertake PhDs in economics as a career move.

But reflect on the implications of a world of macroeconomics textbooks all teaching the same micro founded, DSGE approach, which my profession tells us is required.

This is the exact approach that delivers the ridiculous forecasts that the IMF makes continuously.

This is the exact approach that predicted austerity in Greece would lead to rapid growth in 2011 and when the economy collapsed further, the IMF had to admit they had calibrated their model wrongly. Oops.

This is the exact approach that allowed the GFC to build up over several decades and then explode without any of the practitioners of that approach seeing it coming or knowing what to do when it arrived.

Remember the comments made by Nobel Prize winner Robert Lucas Jr (University of Chicago) in his 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association:

My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. There remain important gains in welfare from better fiscal policies, but I argue that these are gains from providing people with better incentives to work and to save, not from better fine tuning of spending flows. Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management.

So the ‘business cycle’ was dead and all that governments should do was to further privatise and deregulate.

At the time, the private debt buildup and the pursuit of fiscal surpluses was leading to a perfect storm. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists wrote about the impending crisis even during the 1990s – it was not a matter of if, but when and how bad it would be.

The mainstream with their were blithely unaware.

Those modern New Keynesian models typically didn’t even have a financial sector in them because they didn’t think ‘money mattered’.

It is clear that the mainstream of my profession spend their time propagating a macroeconomics literature that has zero predictive content. We know that because Robert Lucas was wrong – the business cycle was far from dead and just four years later the financial system collapsed and we are still picking up the pieces.

It is no surprise that the mainstream macroeconomic models didn’t predict the crisis – their macroeconomic models assumed stability, did not have financial sectors (banks etc) built into the models, and were underpinned by the biased view that free market would optimally self-regulate.

That is the approach that appears in all the mainstream textbook in macroeconomics.

Our textbook will take a completely different approach.

And it is not surprising that the first point of call for governments in late 2008 who were facing the meltdown of their entire financial and production systems was the so-called outdated approach that MMT economists advocate.

The policy makers didn’t turn to DSGE New Keynesian models – they used an approach that is outlined in our textbook.

One could never understand the last 25 years of Japanese economic history using the approach taken in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks.

One could never understand wage developments in the real world using a rational expectations NAIRU approach which is embedded in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks.

It is not suprise that they didn’t see the GFC coming and couldn’t explain how to get out of it.

But the neo-liberal Groupthink is so strong and the denial is so pervasive that these characters go through their careers with blinkers on.

When a chink of the real world enters their stultified lives and they realise there is a problem, the denial resonates strongly and some ad hoc rationalisation occurs, followed by historical revision (it won’t be long before they deny the GFC actually occurred).

Times are changing within the economic profession – it will take time. But our book and others that will follow like it will be benchmarks as that change goes through.

Conclusion

A slightly different sort of blog.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2017 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“the IMF always predicts stronger growth than occurs when it is advocating imposing austerity (thereby understanding the costs of the policy).”

That’s not fair. The IMF always predicts stronger growth than occurs full stop.

The human propensity to shoot the bearer of bad news means that it, like every other large political body, is bound to be biased towards optimism in its forecasts if it wants to avoid being shot.

Dear Bill,

Thrilled by news of your book, I searched Amazon. They have it coming out in December 2017 or early 2018. Is that right?

I read the article in the Age. Forecasting is always a dicey business but that said it was most heartening to see that MMT forecasts came out so well. Let’s hope it helps to spread the message. Well done!

Hello Professor Mitchell,

Have you seen Professor Perry Mehrling’s course called ‘money and banking’.

[Bill deleted a link he does not wish to promote]

He promotes a view called the ‘money view’ which basically explain the monetary and banking system via balance sheet views of the different actors involved. Much of the course overlaps a lot with your content on MMT and it seems like there is a need to reconcile the two views. I would be interested to know your more informed opinion on this. Thanks!

” . . . and couldn’t explain how to get out of it.”

‘They’ thought they didn’t need to?

‘They’ assumed that the economy was ‘self regulating’?

Mervyn King {Thursday 11 September 2008}.

“In the UK we face a difficult but, temporary, period during which inflation will remain high for a while and output growth at best weak. But provided we do not impede the required adjustment we will come through this temporary period and resume a path of normal economic growth with inflation close to target.”

I’ve been shocked at the ideology in academic economists. I admit to naivete.

The same naivety I had as a child when I thought parliament realistically debated the merits of legislation.

I expected more in adulthood. However it is the same naivety that now makes me detest shows like Q&A where it becomes more like a radio talk show with one view or playing political ‘gotcha’ games. Real merits of policies are never discussed. It is just political PR.

That said wont you now cop more flak from those ‘referees’?

I think I’ve been around this blog since 09 (maybe earlier) and I remain because the logic makes sense. Where I have thought I have found holes in the past have been corrected or explained to me either here or via another MMT academic.

And for the most part, on the blogs, you do not speak in economic jargon.

Dear Harry (at 2017/02/06 at 6:49 pm)

Thanks for your comment.

I am familiar with his work and would suggest it runs contrary to much of MMT’s. But I don’t wish to spend time discussing his work any time soon.

best wishes

bill

Therefore, basing their knowledge on this book will be a dead end for their career in economics.

That is a topper, though consistent with rational expectation theory.

If you wnt to graduate, get with the programme, or go get yourself buried son

What would a rational person expect to with that sort of guidance?

At least science has confirmed why this blinkered approach arises and is so persistent.

“Neural correlates of maintaining one’s political beliefs in the face of counterevidence”

This is why “when the facts change I change my mind” is such an important part of Keynesian thinking. Actually it is very, very difficult to do that.

Dear bill,

Thanks for the reply. If you could quickly point me to a post of yours that points to a difference b/w his money view and MMT that I could read through, I’d much appreciate it. Not asking for an elaborate post, just a link. Thanks!

We really have to start denigrating these fraudulent “Nobel” prizes for economics. The Swedish Bank promotor talks about their prize as a “homage” to the real Nobel prizes. It’s nothing of the sort and is a canker on the genuine Nobel institute. You have be an insider in the mainstream mould to be eligible. It carries a lot of undeserved clout and is used to legitimise mainstream thought.

I can hardly wait for the chickens to come home to roost, well overdue though it is.

Harry,

Isn’t Mehrling connected with INET, the George Soros initiative?

“the path of aggregate spending is irrelevant”.

They apparently haven’t read Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken”. Shame on them. The relevant lines are:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and I.

I took the one less traveled by

And that has made all the difference.

Quite. The mood of the narrator isn’t entirely clear, but wistfulness may be his state of mind (I am assuming a man due to when Frost wrote the poem, but the narrator could easily be a woman.)

As you make clear here and elsewhere, wistfulness is an alien state of mind to neoclassical economists. Mankiw, when the students boycotted his course in a protest, stated in a NYT op-ed that he was disappointed that they were rejecting the wisdom he was putting across to them. The contention of the students was that he was engaged in nothing more than propaganda. As expected, the university, Harvard, stood up for Mankiw. Something similar happened in Manchester, except that the university fired a temporary lecturer the students had persuaded to present more heterodox views.

They don’t seem to be able to do anything other than dwell in the trench they have dug for themselves and fire misaligned salvos at critics. It would be pitiable were it not so dangerous.

Bill,

How about 2017 forecasts?

Or is the latest political turmoil e.g. Trump, Le Pen etc just adding to the uncertainty in forecasting!

Harry: I am no expert MMTer, merely a great admirer and student of it, but there is an interesting comment, by the well-known MMTer Eric Eric Tymoigne, following a post on the famous MMT site, New Economic Perspectives, which may provide some of the insight you want. The original blog post, by Randy Wray (Bill’s sometime collaborator), is entitled: DEBT-FREE MONEY: A NON-SEQUITUR IN SEARCH OF A POLICY (http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/07/debt-free-money-non-sequitur-search-policy.html ) Eric Tymoigne highlights a main difference between MMT and Mehrling’s money view, i.e. that MMT-ers promote the notion of tax-driven money, whereas Mehrling accepts that gold is money, as opposed to a commodity like Bitcoin, bananas, or sea-shells. According to Wray, tax-driven money, or state money, or chartalism, has been the standard operating procedure of all sovereigns for at least 6000 years.

Here is the actual exchange:

Arnold Wentzel | July 2, 2014 at 7:24 am |

So, if you thought of money as being “debt-free” you would believe that money should have intrinsic value (or insist that it should have intrinsic value)? I remember listening to Perry Mehrling’s lectures on Coursera, where he placed gold at the top of the money hierarchy, explaining (if I remember correctly) that it is at the top because it is someone’s asset without simultaneously someone else’s debt.

Eric Tymoigne | July 2, 2014 at 4:05 pm |

That’s right. And in the same vein cars, potatoes, and carrots are money.

Arnold Wentzel | July 2, 2014 at 7:38 pm |

…and, of course, bananas…

Incidentally, I also took Prof. Mehrling’s course, and he provides some interesting operational information, but IMO his account is less coherent than that of the MMTers.

Howdy Professor Bill,

My question is off the topic a bit, however I cant find an email for u so thought I would ask here.

I have been reading the 1959 Reserve Bank Act and it states that its number 1 aim (of 3) is the “stability of our currency”. How does that fit with the idea that floating the currency was meant to mean our exchange rate adjusted for our trade performance? are negative capital inflows (such as our banks large foreign borrowing for asset speculation), proof that the RBA and regulators are knowingly preventing this adjustment and therefore sacrificing local industries who cant compete as the dollar is maintained too high?. In doing so, are they contradicting the RBA 3rd aim for “the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia”?.

Seems to me both gov’ts who favour the free market don’t do so in policy, export parity pricing for gas and the rigging of interest rates that drive these negative capital inflows (and in doing so keep our dollar high, to the detriment of local industries) are examples of this hypocrisy.

I hope my thoughts/questions makes sense to u?

“The mainstream macroeconomists barely have unemployment in their models – they think it is a voluntary, optimizing choice that workers make not to work some times. Their models do not consider underemployment or the casualization of the labour market – those real world events are below their DSGE radar.”

This blew my mind. Also, I had to google UNSW to see what institution it is. Turns out it is a university in Sydney. As you have pointed out: a country only limited by real resource constrains–a sovereign government has no financial limit. I think they’d also say public debt is too high. Funny how they worry about things that are just fine but not worry about unemployment, which leads to many social ills. Misleaders have probably wasted decades by using neo-liberal economics and certainly hurt many people and wasted their potential to have fulfilling lives.

Before I started learning economics, I could smell something was wrong when all the conservatives kept saying economy is going to do this or that but never came about. Turns out that they don’t have monopoly of being wrong–left right and center, the whole thing may be rotten.

Larry, I have reading that short book on Thatcher by Kaldor. I have also been reading 23 Things They Don’t Tell You by Ha-Joon Chang. They both point out this Neo-liberals/monetarists fetish of private sector in that everything it does is correct. I loved this quote by Kaldor:

“The fundamental error of free market philosophy resides in the notion that profit is the true and the only relevant criterion for deciding whether a particular form of economic activity is of benefit to the nation”

It is so succinct in describing the narrow-mindedness of monetarists.

Finally, on Mr. Chang. In his book, he has said a few times that the GM bail out costed taxpayers’ money. I don’t think it did right? Certainly nobody is collecting tax dollars at the federal level by decreasing people’s bank accounts or tear up dollar bills (concept from 7DIF), but then somehow rematerialize those dollars to bail out GM. Of course, the congress people would think that the government has less money now because it has bailed out GM. Maybe somehow they will make them more reluctant in funding programs, but I never see them reluctant to fund the DoD.

Regarding Harry and Marian thread regarding “Money view” vs. MMT:

Mehrling has the style of an ecumenicist- He refers to the “many views of truth” parable of the blindfolded people with particular true, but limited view of the elephant. He protests that he is neither a chartalist nor a metalist. Neither a Monetarist nor a Keynesian. He presents a mediated theory of truth, arguing “It’s better to know two theories which claim to be opposites- because both of them are true- in some dimension. Both of them are true about the part of the system they are talking about, but not about the whole system.” So it is fair to ask what is the language that mediates between these two languages. Here we see the institutionalist’s language and the centrality of Mehrling’s references to Copeland. The institutionalist has a profound skepticism of theory and instead advocates a supposed empiricism- in Copeland’s and Mehlings case- of the balance sheet. This perspective resonates with many in the business community as well as those confused and eager for an escape from the demands of attempting to comprehend the deeply variegated and heatedly contentious views of competing economic schools. As Mehrling puts it- “I find this balance sheet approach very helpful for letting us know when one approach makes sense and when we should be focusing on the other approach. Because this [the balance sheet] is always true”

Setting aside the question of what is being measured by a particular balance sheet, let’s instead examine the “when” condition that mediates this gestalt switch that tells us “when one approach makes sense”. Mehrling distinguishes between “normal times” and times of crisis. Of course, nearly everyone agrees we have a hybrid system- that the central bank is at times a banker’s bank that supports the goals of private markets- and at other times a government bank that serves public concerns for social welfare. A pragmatist approach can be presented where either one or the other of these two concerns should be dominant. What is Mehrling’s view? I think he is pretty clear about it in multiple examples. Mehrling views the norm as erring on the side of the decentralized and non ideological mediating role of the market. Mehrling accepts the role of the state, but mostly as a safety net, that the state must step in during times of emergency- either when money markets massively screw up, or in times of war. There are other pragmatist views that assume social goals as dominant with the market instead in the support role- but this does not appear to be Mehrling’s perspective.

I am not saying Harry that it is unfair to see a relationship between the MMT view and Mehrling’s “money view”. There are many possible conflations between MMT accounts and Mehrlings themes, it is just that it is hazardous for me to speculate which of the numerous possible perceived intersections you have in mind. Perhaps you could tell us more in this regard. My view is that Mehrling provides many interesting stories regarding operational details of the current money system, but his sometimes engaging storytelling tells a very different overall narrative than that told by proponents of MMT.

In the absence of clear understanding of your view of the intersection of the two perspectives, may I suggest you test your hypothesis by undertaking the time honored technique of “knowing the difference by looking at their fruits”- that is, gaining a quick read of the two perspectives by contrasting the major policy recommendations coming from the two perspectives. Though not a universally reliable test, this can be revealing as I think is the case when comparing MMT to Merhling’s evaluation of what the money system is for. As presented in his recent book and emphasized at multiple places in his youtube lectures, in Mehrling’s view, governments must make a second Lombard street realization- not just that Central banks need to be a Lender of last resort, but that they already have functioned and we should canonically accept their role as a Dealer of last resort. Mehrling’s policy recommendation is that in emergencies, Central banks need to step in and backstop not just banks but money dealers- by taking opposite sides of transactions in situations where the liquidity of the system has evaporated and the system is collapsing.

Contrast this with the general policy recommendation of MMTers. Their focus is not primarily on emergency scenarios and backstopping private money market liquidity, but on government backstopping of the labour market. The shift in accounts is a gestalt- not so much differing on facts- though there are substantial disputes on this score- but which facts are important and how those facts are woven together. Mitchell, Wray and their brethren focus on the situation of workers and the impact the central bank can have on flows of money to under-utilized labour resources. Mehrling focuses on interruptions of flows of money to capital markets.

Though I think this sort of 10,000 foot view is revealing, the details of the theoretical differences between their economic schools are substantial and important. It is easy to overlook Mehrling’s pointy elbows, because he does not adopt the polemical or prophet style and instead presents his information wearing the garments of the ecumenicist. But to be fair to his views, you must go beyond his preferred pedagogical approach and examine the people he regards as his intellectual forefathers. The lay of the land looks substantially different from his view than that of MMTers and other Post Keynesians. A cursory examination of the literature will reveal considerable substantiation or this evaluation. Again, without getting into details you can example citation patterns. For example, though Lavoie has kind things to say about Mehrling’s expertise regarding the mechanics and historical foundations of modern money markets, and though he appreciates his institutionalist (eg Copeland et al.) approach of a balance sheet flow of funds analysis of the money market, you will not see a single reference to Mehrling within Lavoie’s Post Keynesian economics textbook. You will see instead see references to names familiar to those on this blog- Bell-Kelton, Mosler, Wray, and of course Professor Mitchell. Though there are significant bones of contention between MMT and other Post Keynesian perspectives, I would think Lavoie’s assessment is fair and that Mehrling would agree- he is not even in the Post Keynesian camp. Given this, it is reasonable to expect that Mehrling would agree that there is as great if not a greater gulf between his perspective and that of MMT.

Nonetheless, it is helpful to understand where readers see commonalities between MMT and Mehrling’s perspective and I was sincere in my request to hear where you see such intersections.

Survey about groupthink at the link below. Not desperately scientific – just a bit of fun.

http://markwadsworth.blogspot.co.uk/2017/01/fun-online-polls-group-think-usa.html

Tom, you are right that Change is wrong about taxpayers’ money. Taxes don’t fund anything, though they perform other functions for society. Your mention of being able to fund, say, DoD, is an example of the principal actors probably lying about what they are doing. Samuelson, on the other hand, thought it necessary to propagate this lie in order to prevent government allowing spending to get completely out of control. Either he was a tad paranoid or he knew something the rest of us don’t.

I can recommend an article from the 1940s on just this subject, just to show how far down the falsehood trail neoclassical economists have traveled. It is Beardsley Ruml’s “Taxes for Revenue are Obsolete” that appeared in Foreign Affairs in 1946. It is a good read; I highly recommend it. A search for that title should bring it up.

Something happened with the spelling of Chang’s name.

Neil, I would be rather suspicious of such reductionistic explanations of psychological states by means of neural firing patterns. By the way, your link does not work.

Thanks for the article suggestion Larry.

I am not sure that hiding the truth of that government can fund anything is good for bad. Certainly, its scary given what our US government has done around the world with bad ideas like spreading democracy and market freedom recklessly, but what if Americans are less impovished that they demand more democratic government or toss out the corporate lapdogs? Though, with so much propaganda and no real information, its hard to say where that would have led to.

Bill, Great news that this important new book on macroeconomic reality will be published later this year. I feel the tide is changing albeit very slowly!

Harry,

Mehrling is an opponent of MMT. In short he can’t get past the notion that a government that is the monopolist supplier of its own money could have no budget constraint in terms of its own money. He also has issues with the government being an employer of last resort, and the ability of governments being able to maintain price stability

under the MMT / JG proposals.

In saying that he’s still an infinitely better economist than that goose from UNSW.

@alan dunn Marian harry

Perry’s is not “an opponent of MMT”.

He is completely okay with currency issuing govt not being currency constrained,he hints at this directly in some of his work.

He has never expressed hostility towards the government being the employer of last resort,he just doesn’t focus on employments levels.

Nor is his hierachy of money instructive,the model makes sense for fiat,it merely includes gold at the top (as an optional for pre’72 system)because Walter Bagehot had a similar framework: and in his time international payments were settled in gold.We now have free floating exchange so international trades are settled in US dollars or in the domestic currencies.

perry mehlring notes that central bank is forced to act as dealer of last resort to prevent volatility in the capital markets.Mostly perry just describes how the private dealer money markets operate and interact with the Central bank.