Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

When the term ‘progressive’ loses all meaning …

The UK Guardian newspaper began life as the Manchester Guardian in 1821 as an artifact of the cotton mill owners who were opposed to the reform movement (for parliamentary representation to alleviate the mass unemployment and poverty that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars). The suppression of the reformist agenda culminated in the Peterloo Massacre the cavalry charged into around 80,000 protesters killing and injuring many of them. The police closed the newspaper (Manchester Observer) which had been sympathetic to the reform movement. Step in one John Edward Taylor, a cotton merchant, who established the Manchester Guardian to advance the interests of the capitalists. After a period under the editorship of C.P. Scott, where the Manchester Guardian was significantly more progressive in outlook (for example, supporting the Republican government against Franco; supporting women’s suffrage), the paper has increasingly become a neo-liberal propaganda machine with respect to its economic coverage, irrespective of progressive positions that might take on other issues (for example, its criticism of Israeli government policy). It now rarely publishes anything on economics that passes muster.

When I lived in Manchester in the 1980s (studying for my PhD), I did some archive digging of past issues of the working class newspaper in the region the Manchester and Salford Advertiser, which was highly critical of the Manchester Guardian in the early 19th century.

The Manchester Guardian was anti-worker, opposing strike action for better pay and also reduced working hours. Taylor used it as a vehicle to undermine the growing and organised working class leadership.

For example, it opposed the Ten-Hour Movement, which sought to reduce “the working day for children under 16”, which led to the 1833 Factory Act. That act led to some restrictions in the hours children could work in the cotton mills. While it was progress, the allowable conditions are preposterous by today’s standards.

The Manchester Guardian, the voice of the mill owners, claimed the legislation would render the British mill noncompetitive in the face of foreign competition.

On May 21, 1836, the Manchester and Salford Advertiser referred to the Guardian as “the foul prostitute and dirty parasite of the worst portion of the mill-owners”.

It was accused of being “the cotton lord’s bible” by Richard Oastler, who although a Tory businessman pushed the Ten-Hour reforms in sympathy for the travails of the children.

Reading the Guardian these days suggests that its defense of the interests of capital continues although the type of material it is choosing to publish under the macroeconomic debate heading advocates policies that undermine capital – or at least productive capital.

Here are two quotes:

Unfortunately, [nation name suppressed] remains on a dangerous long-term fiscal path, with deficits rising as a share of GDP in 2016 for the first time since the end of the Great Recession in 2009.

And the second quote::

It is not a good look when the deficit continues to grow and government debt is rising at a rapid pace. The credit ratings agencies are no doubt circling, looking to downgrade [nation name suppressed] credit rating. If the policy approach to the budget deficit is to bury important news on a Friday afternoon and not talk about it, the downgrade seems assured.

Which think tank do you guess wrote these assessments?

You would be forgiven for concluding they both came from think tanks such as the Peter Peterson Foundation, which in fact the first of the quotes is attributed to (Source).

The second quote actually comes from an author who signs of as a “research fellow at Per Capita, a progressive thinktank”. This is an Australian outfit.

Progressive?

This is how far we have moved to the right. When a self-proclaimed “progressive thinktank” can write that sort of tripe.

Even emphasising the credit rating agencies – giving them any credibility – is neo-liberal in inclination.

But before we consider the rest of the narrative presented by the author of the second quote lets provide some context.

National Accounting and other facts for Australia

Let’s start with some facts – National Account type facts.

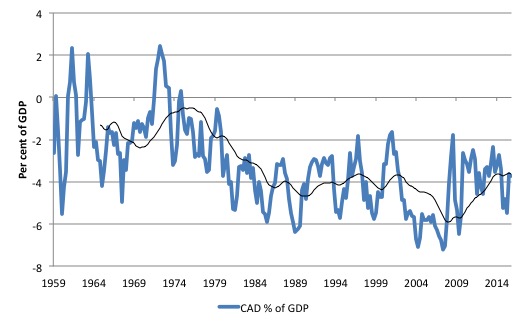

The Australian external sector has overall been a negative growth factor for many years. The last positive current account balance was in the June-quarter 1975 and that was an aberration.

As you can see from the following graph, almost as long as we have coherent National Accounts data (under the new framework which began in the September-quarter 1959), the current account has mostly been in deficit.

The black line is a 24-quarter moving average, which shows that despite fluctuations up and down the deficit has been relatively stable at around 4 per cent of GDP since the mid-1980s.

Important to understand that the current account is not the balance of trade, the latter which is sometimes in surplus but is always swamped by the so-called invisibles (the net income flows abroad).

So from this graph we know that at least one component of the non-government sector is always in deficit (that is, the nation as a whole is spending more than it is earning with respect to external transactions).

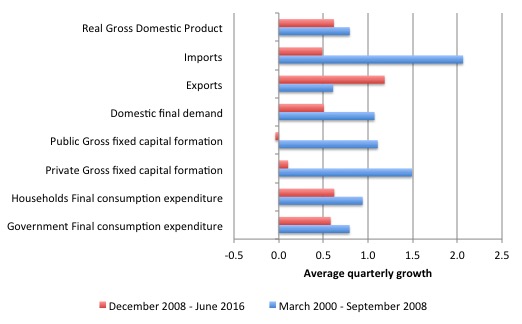

The next graph shows the major expenditure components (in real terms) that contribute to Gross Domestic Product. The columns are the average quarterly growth rates for the two periods shown: (a) the growth period prior to the crisis; and (b) the period after the peak real GDP in the September-quarter 2008, which was followed by a slowdown that was arrested by the emphatic fiscal intervention in late 2008 and early 2009.

It doesn’t take much to work out that the private spending components (household consumption, private capital formation) were growing more robustly prior to the crisis than they have been since September quarter 2008.

Indeed, private gross fixed capital formation has almost ground to a halt (as the mining investment phase associated with the record commodity prices as well and truly terminated).

The result has been a dramatic slowdown in real GDP growth – from an annualised 3.2 per cent to an annualised 2.4 per cent. Real GDP growth is now well below the previous trend and as a result the broad labour underutilisation ratios are around 15 per cent.

That is 15 per cent of the available and willing labour force in Australia is currently either unemployed or underemployed (the latter group indicating they would desire around 15 extra hours on average per week).

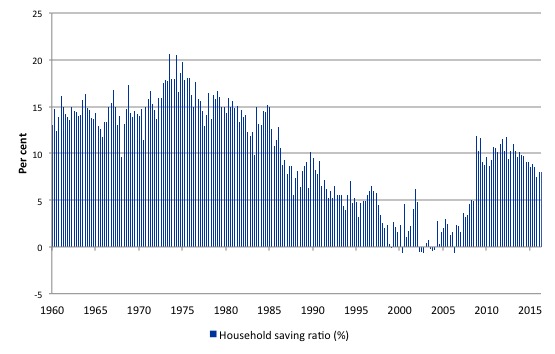

The moderation in household consumption spending growth is allied to the return to a positive saving ratio.

Up until the mid-1980s (from the late 1950s), household saving averaged 14.8 per cent of household disposable income.

As a result of the suppression of real wage growth relative to productivity, which began in the mid-1980s as government policy attacked the capacity of trade unions to defend wages and the financial market deregulation that also began around then, households could only maintain consumption expenditure growth through credit.

They were pushed hard by the financial engineers who found a new playground to push credit onto almost anyone as financial market oversight and regulation was reduced.

The household saving ratio plummetted into negative territory by the early 2000s.

Prior to the crisis, households maintained very robust spending (including housing) by accumulating record levels of debt. As the crisis hit, it was only because the central bank reduced interest rates quickly, that there were not mass bankruptcies.

After the GFC hit, the household sector sought to reduce the precariousness in its balance sheet exposed by the GFC.

In June 2012, the ratio was 11.6 per cent. Since the December-quarter 2013, it has been steadily falling as the squeze on wages has intensified again.

While the recent trend has been downwards, it is unlikely that households will return to the very low and negative saving ratios at the height of the credit binge given that the household sector is now carrying record levels of debt.

At some point, household consumption growth will fall unless growth is supported by public spending (given the poor outlook for private investment and net exports).

This also means that government surpluses which were strong>only were made possible by the household credit binge are untenable in this new (old) climate.

The Government needs to learn about these macroeconomic connections. It will learn the hard way as net exports weaken if it tries to impose austerity.

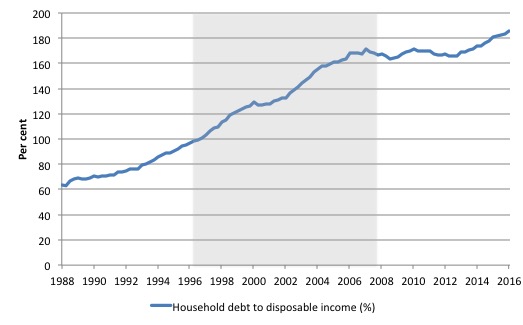

The financial credit binge has left households with this debt profile. The grey shaded area is the period that the federal government ran fiscal surpluses as a result of the private sector spending binge.

It was unsustainable. The rising fiscal deficits from 2008 as a response to the GFC allowed the household sector to save a higher proportion of its disposable income (as above) and reduce its debt ratio.

The squeeze on disposable income in recent years as the government fails to expand its fiscal deficit in the face of declining private spending growth has seen the ratio rise again.

It is an unsustainable growth strategy to think that the government can return to surplus and the non-government sector will increase its already record levels of debt. It won’t happen and if the government tries to push for fiscal consolidation a recession will surely result.

In May this year, the Federal government delivered its latest ‘fiscal statement’ (aka ‘The Budget’) and the economic predictions, which underpin that statement are contained in Budget Paper No.1.

At the time, the Treasury was forecasting the following outcomes:

1. The fiscal deficit for 2015-16 of -2.4 per cent of GDP reducing to -2.2 per cent of GDP in 2016-17, then -1.0 per cent (2017-18), -0.5 per cent (2018-19) and -0.1 per cent (2019-20).

2. The current account deficit to be at 4.75 per cent of GDP in 2015-16, -4 per cent in 2016-17 and -3.5 per cent in 2017-18.

I note that the average current account deficit since fiscal year 1974-74 to 2015-16 has been -3.9 per cent of GDP. So we might consider that sort of performance to continue over the fiscal projection period. There is certainly no expectation that the current account will suddenly record close to balance results over the fiscal forecast period.

So what does that mean in terms of the sectoral balances?

Remember that we can derive a relationship from the national accounts between spending and income for the three-major sectors in the economy: (a) the external sector; (b) the private domestic sector; and (c) the government sector. (a) and (b) sum to be the non-government sector.

The sectoral balances must hold as an accounting statement and we then need to interpret their evolution by understanding what drives the individual balances.

Please see – Answer to Question 3 – for the complete explanation of the sectoral balances approach and derivation.

The final sectoral balances expression that results from that derivation is that:

(S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

where S is private domestic saving from disposable income, I is private domestic capital formation investment, G is total government spending, T is government taxation receipts, and the CAD is the current account deficit (the trade deficit plus net income transfers abroad).

The sectoral balances equation is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

This allows the private domestic sector to save overall (which is different from household saving out of disposable income denoted S above). That means, the private domestic sector is spending less than its total income and building wealth in the form of financial assets.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T less than 0) and current account deficits (CAD less than 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

The previous expression can also be written as:

[(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

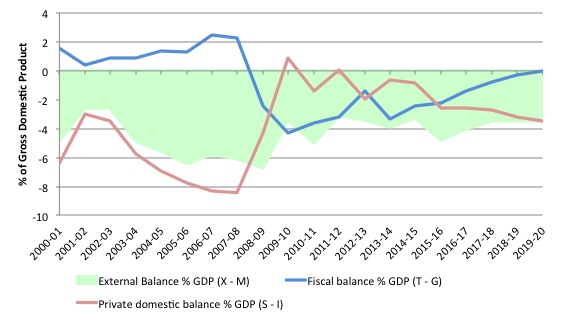

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2019-20, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in ‘Budget Paper No.1’ and the current account position assumed constant at the 2017-18 estimate of -3.5 per cent of GDP.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) more or less projected to be constant over the forward period, the private domestic balance overall (red line) is the mirror image of the projected government balance (blue line).

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09, which saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit – and this not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to rebalance its precarious debt position.

The fiscal strategy outlined by the Government in May 2016 suggests (see graph) that the private domestic sector will once again be accumulating debt as it progressively spends more than its income.

We are on the path back to the excessive private domestic debt levels that prevailed before the GFC.

Further, the fiscal estimates suggest that total private investment will decline by -11 per cent in 2015-16, -5 per cent in 2016-17 and be static in 2017-18.

So for the private domestic sector to move from a deficit of -2.6 per cent of GDP in 2015-16 to -3.5 per cent of GDP in 2019-20, with private investment in sharp decline or static (in the final year), implies that the household sector is going to have to be spending much more than its income, and, increasingly so, for the overall sector balances to have any coherence.

That would mean the implied build up of private sector debt will be borne by the household sector, already carrying record levels of debt.

But, then you examine the other fiscal projections in Table 1 of the Economic Outlook, presented in Budget Paper No.1 and the outlook for household consumption and dwelling investment are fairly constant or falling (in the case of homeinvestment).

So the question then is obvious – where is all the private domestic sector spending implied by the sectoral balances analysis going to come from?

The answer is also obvious: the Treasury estimates are inconsistent. They do not add up. Which would not be the first time that observation has been apparent.

In other words, the fiscal estimates provided by the Government are concocted in an ad hoc manner which little recognition of the underlying relationships that have to hold between the three macro sectors.

If the projections are to be believed then the Government is expecting the private domestic sector to maintain the growth in the economy by increasing its indebtedness.

That would mean we are heading in the same direction as before the crisis – growth becomes reliant on private debt buildup.

The whole nation is transfixed on fears that the government debt in Australia is too high – courtesy of all the scaremongering that has been going on. But nary a word gets mentioned about the dangerous private debt levels. It is true that most of the debt is owed by higher income people in Australia, which makes an insolvency crisis of the likes of the sub-prime less likely here.

But the reality is that the debt levels and the growth in them (about the same as disposable income) means that consumer spending is likely to remain fairly subdued overall. It is unlikely we will see a return to the pre-crisis period when debt grew much faster than disposable income and the resulting spending maintained stronger economic growth.

So what does a so-called progressive commentator think about all this?

In the UK Guardian article (October 3, 2016) – Credit downgrade assured if Coalition keeps hiding from its debt and deficit disaster – our alleged progressive analyst claimed that with the football grand final hysteria gripping the nation and families heading off on school holidays, the federal government decided to publish the “final budget outcome for 2015-16 on the Treasury website”.

Probably a good thing in fact. The actual fiscal outcome is somewhat irrelevant given it should never be an object of policy in itself.

What it is at any point in time doesn’t matter at all. How we interpret its movements and level in terms of the real economy is what matters.

The author, however, thinks it is an act of deception to release this data under the cover of ‘good times’ (footy, holidays etc).

I agree with him that the current behaviour of the federal government – in terms of not saying much about the 2015-16 fiscal outcome – is inconsistent with the rhetoric it used to gain power from the Labour Party, first in September 2013 and again in July 2016.

In Opposition, the currrent government prophesised doom and a desperate neet to engage in “budget repair” because there was a “budget emergency” etc.

The UK Guardian author is correct in pointing out that hypocrasy. The point was that there never was a fiscal emergency. There never was a need to “return to surplus” or to be “paying off debt”.

The UK Guardian author should have made that point as he criticised the government for its hypocritical manner.

But instead he claims the reason the government released “the budget outcome document … in the shadows of the Friday night without any fanfare” is because it contains disturbing information.

What might that be?

Shock horror – he writes:

The 2015-16 budget deficit was $39.6bn or 2.4% of gross domestic product. When the former treasurer Joe Hockey delivered the first budget of the Coalition government in May 2014, the budget deficit for 2015-16 was forecast to be $17.1bn.

And we should, as a nation, be thankful that the fiscal deficit has increased in that time.

Why?

Because otherwise, given the external sector draining growth and the moderation in private domestic spending growth, Australia would have been in or close to recession had the government imposed austerity to ensure the deficit was smaller.

In part, the rising deficit is due to automatic stabilisers kicking in – the falling tax revenue as private spending growth moderates.

But as the UK Guardian author says, the government has also increased spending – although he doesn’t note that in several quarters the difference between negative real GDP growth and the actual outcome has been the government contribution to real GDP growth.

He prefers to dramatise that the government “has been spending at an alarming rate”. He claims:

In 2012-13, the last full year of the previous Labor government, the ratio of government spending to GDP was 24.1%. In 2014-15, this had risen to 25.6% and, in 2015-16, it rose to 25.7% of GDP. The 1.6% of GDP blowout in spending between 2012-13 and 2015-16 is about $26bn and accounts for more than the blowout in the deficit from the time of the 2014 budge

As if that is bad. The rising proportion of government spending has been, thankfully, helping to offset the massive decline in private capital formation – as it should.

Without it, we would have been in recession with even higher unemployment and underemployment than is currently the case.

The UK Guardian author discusses the “deficit blowout” – which is just metaphorical talk for a rising deficit. The terminology used in the article is designed to scare and add shock value to some simple, relatively meaningless numbers.

He never mentions the unemployment rate or household debt or underemployment or the record low wages growth!

Soon enough we read that the:

The deficit blowout fed into the level of government debt as it had to ramp up its borrowing to cover the ever growing shortfall.

And there has been a long queue of those on the corporate welfare that is public bond issuance lining up at each auction to get their greedy hands on the risk free assets.

Bid-to-cover ratios remain high.

But the statement that the government “had to ramp up its borrowing” is a lie. It didn’t have to do that at all. It could have instructed the central bank (RBA) to engage in Overt Monetary Financing to match the increased net spending.

Building in voluntary behaviours (such as issuing debt to match net spending) as if they are laws of nature (“had to”) only serve to mislead the public into thinking that government have to behave in this way.

The progressive option is not to issue debt at all and use the currency-issuing capacity to maintain full employment.

The UK Guardian author writes on debt:

Gross government debt, according to the final budget outcome documents, rose to $420.4bn, or 25.5% of GDP, in June 2016. This is at the highest since 1971-72 when the Vietnam war effort was being funded.

Which is ambiguous in one sense and irrelevant in all senses.

The level of gross government debt is “at the highest since 1971-72 when the Vietnam war effort was being funded” but GDP is also at its highest level – as is the population – as each minute passes it gets bigger.

But the ratio is very small in historical terms. For example in the late 1940s, the federal public debt ratio (per cent of GDP) was more than 120 per cent (1946 was the peak).

But at any rate, none of this has much relevance to anything other than to confirm that the snouts of the corporate pigs have been in the public debt trough getting their on-going welfare fix.

And then the punch line comes – all this debt – is going to bring the credit rating agencies down on us – as if that is something that is of any relevance at all.

Apparently:

The credit ratings agencies are no doubt circling, looking to downgrade Australia’s credit rating. If the policy approach to the budget deficit is to bury important news on a Friday afternoon and not talk about it, the downgrade seems assured.

Please read these blogs among others:

1. Ratings firm plays the sucker card … again.

2. Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies.

3. Ratings agencies and higher interest rates.

Conclusion

If the sort of analysis presented in this UK Guardian article is representative of a ‘progressive’ position on government spending and debt then the term has lost all meaning.

The article is just the usual neo-liberal lies peppered with emotive metaphorical language that is designed to cover up the lies and invoke fear and tension in the readers.

It has no credible basis in a macroeconomic theory that is based on the way the system actually operates.

I think the ‘think tank’ should change the way they advertise themselves. This narrative is the anathema of progressive thought.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Can anyone provide instructions on how to compile the sectoral balances for Australia?

Dear Allan

1. Data is available for Current Account Balance (see RBA statistics) and the Fiscal Balance (go to http://www.budget.gov.au and look at the Appendix of Paper No. 1 (Historical data).

2. Then calculate the private domestic balance as a balancing item knowing that the balances have to sum to zero.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

If you thought that article was off colour, check out Prof. Ross Guest’s assertion that federal governments are mistaken in their continuing stimulation of the economy. The Conversation 4th October.

Dear Bill

Since the seventies, Western countries have become more neoliberal and also more politically correct. So, economically the right has been winning, but in other areas, the left has been ascendant. Nowadays, leftists seem to be more preoccupied with race, gender and sexual orientation than with class. Senator Elizabeth Warren was a professor at Harvard, where she was rather unusual because she is the daughter of a blue-collar worker. However, she preferred to present herself as the first Amerindian professor. After all, one of her 32 great-great-great-grandparents was an Amerindian. Harvard reserves 8% of its undergraduate places for “blacks”, but does it reserve any places for students whose parents didn’t finish high school? “Blacks”is between quotes because in the US, a person can be “black” even if he/she has mainly white ancestry.

Regards. James

“”Blacks”is between quotes because in the US, a person can be “black” even if he/she has mainly white ancestry.”

It’s ironic that in the days of slavery, black ancestry of whatever degree qualified a person as “colored” and therefore a non-person before the law.

For example, President Thomas Jefferson’s reputed slave-concubine and mother of several of his children, born into slavery, was one sixteenth black and she was the half-sister of his deceased wife.

Now some people are outraged that others with a non-white ancestry have the audacity to claim it.

Yes the mass media are rubbish. At least the tide has turned against neoliberalism.

Bernie Sanders would have been the next U.S. President if not for the corruption of the Democratic Party and most of the mass media. Stephanie Kelton was I assume advising Bernie on macroeconomic policy. The TPP may be rejected by the U.S. Senate. Donald Trump’s attacks on declining living standards and on the free trade agreements are very popular.

Jeremy Corbyn is making headway in the UK Labour Party with a mostly traditional socialist agenda. Brexit was to a large extent a rejection of neoliberalism – excessively free trade, loss of democratic control, fraudulent privatisations, off shoring of manufacturing, blind faith in the banking/finance sector and the hipster economy, declining wages, foreign residents undercutting local workers, excessive unemployment and declining government services.

Throughout Europe hatred of the traditional political parties and of the establishment , the EU’s undemocratic institutions, corporations – especially banking/finance, business lobbies and the mass media, that repeatedly betrays the vast majority of citizens in favour of the capital controlling elites is growing with voters turning to the left and right and no longer being afraid of radical choices.

Australia’s duopoly is despised by many despite the complicit mass media. The Liberal vote last federal election was considerably worse than the previous federal election and the Coalition government was saved by the National Parties pork barrelling and blind faith that they can somehow deliver jobs and rural slave labour. Labor’s vote also declined which is very significant with the most noteworthy aspects being the big swing to Nick Xenophon’s centralist and protectionist NXT Party in South Australia and the rise of One Nation in Queensland and NSW which is also protectionist but right wing like UKIP. The Greens made major gains in those few seats that they put in a concentrated effort but also lost ground to NXT in South Australia. The Greens need to learn the art of gaining free media airtime like Donald Trump as most voters remain ignorant or sceptical of their policies. The minor parties and independents received nearly a quarter of the national first preference vote for the House of Representatives but our first past the post voting system, even with preferencing, for the House of Representatives does not produce a fair allocation of seats and this is likely to remain a major obstacle.

The economies of the world are stagnating and the lazy speculative sources of wealth in shares, real estate and mineral resource exports along with fraudulent privatisations and banking scams (apart from superannuation funds management which provides $25 billion p.a. in fees) are not delivering the rates of return as they have in the past, so even some of the capital controlling class may soon be willing to try fiscal stimulus and spending on critical infrastructure or even post war style economic growth to get things moving again. I hear State governments are currently preparing infrastructure priority lists.

The mass media throughout the world denigrates those that are rejecting neoliberalism and the shift to corporate feudalism and calls them ignorant, bigoted, stupid, backward looking, old or populist. This denigrated group may soon be the majority.

Alan

By looking at the trading economics website http://www.tradingeconomics.com/ it shows the budget position and the CAD. From their you can work out the private sector balance.

Govt – PS – FS

-2.4% -2.2% +4.6% = 0

Bill

Can you agree or disagree with the following statement.

If the current account is predominantly in a negative balance then their will always be govt debt.

Its depends on the govt of the day where that debt lays. Howard preferred to push all govt debt onto the private sector and since the GFC the govt has had to bail out the private sector and accept its debt back.

Speaking of irony, it seems likely all modern homo sapiens have their origins in Africa, so categories relating to race are problematic, to say the least, since we all of African ancestry. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recent_African_origin_of_modern_humans).

On the broader topic, I share the frustration of some that identity issues have completely swamped class. While identity is very important it is not everything. For example in the US the near total focus on identity has led to puzzled questions as to why there has been a great increase in the use of damaging drugs by whites, in effect approaching the levels of use by blacks. As noted in the link that follows it has nothing to do with black/white issues and everything to do with class. But since class has been disappeared as an issue there is no language available to express class issues. One result is that many frustrations turn to identity: the muslims or immigrants have unfairly taken this or that. I highly recommend the insights of Professor Fields found at http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2552-barbara-j-fields-we-left-democracy-behind-a-long-time-ago

When the term ‘progressive’ loses all meaning …

—————

All political words have lost meaning, at least in general use?

It’s another aspect to what people have been calling “post truth” politics. Just as people now cherry-pick their evidence they also decide for themselves what words mean. It’s not a new thing – it’s central to Orwell’s 1984 and the ideas underpin his invention of NewSpeak.

My favourite example is the fact that only anti-socialists and Stalin believe(d) Stalin was “a communist”. Never mind Stalin murdered all his fellow revolutionaries? If Stalin was communist, what were the rest of them?

Today I still hear people calling China ‘communist’. How to take that seriously? DoublePlusUnGood.

NewSpeak was intended to limit the thoughts of the party members, eventually to make it impossible for them to even conceive of ideas dangerous to the status quo, the ruling State and its institutions.

I’ve certainly never considered the Guardian socialist but definitely socially progressive. It’s (economically and socially) liberal? MMT isn’t liberal orthodoxy, is it? So I wouldn’t expect it to have much sway at TheGuardian, though I would say the public comments show a clear rise in familiarity with it (MMT).

Still, the entire public discussion of State finance and economics is based on the Housewife’s Budget and has been for most of a decade. Seemingly nobody saying otherwise has any credibility with the public – it’s “the magic money tree” stuff.

Following Brexit, we’ve been told “those that have missed out on the benefits of globalisation” (the workers!) must be listened to, and the country must work for everyone, blah blah blah. And yet when the Labour party suggest investment over austerity, the response in the public sphere is widespread scorn. Apparently people want a different outcome but they’re not prepared to change the things needed to achieve it.

In such a milieu, and when words seemingly mean nothing, there doesn’t seem any point in even trying to rationally change the world. That would demand the public were rational, that words meant something, that facts mattered, that argument matters.

I can’t see anything good coming out of Britain’s increasing schism with reality.

Thanks for that historical account of the roots of the Manchester Guardian, Bill. As a Mancunian I wasn’t aware of the robber Barron origins of the paper.

Another brilliant blog, thank you.

“Its depends on the govt of the day where that debt lays. Howard preferred to push all govt debt onto the private sector and since the GFC the govt has had to bail out the private sector and accept its debt back”

howard and Costello were in part benificiaries of the revenue effects of the private sector debt to gdp ratio blowing out from 100% to 150% during their term in office.

so the government wasn’t pushing anything anywhere, since the banks were the ones importing all that capital and gearing up their balance sheet, and governors of central banks past and treasurers weren’t really into this prudential control malarkey. there appears to be a more recent conversion on the road to Damascus , and as usual long after the private debt horse has bolted.

from what I can see, after every major crisis since the early 90’s, we have witnessed a downward trend in the rate of credit growth, and government present and future forecasts of their financial balance is going to be blown out of the water because of this and as you say the public debt is going to rise, despite whatever spin the current treasurer puts on it.

I think the next problem is going to be so big, that they will have to consider the heresy of all heresies , and consider related party transactions or overt monetary financing, to cover any major collapse in national income.

Dear Tom Hickey

Thomas Jefferson’s girlfriend was 1/4 black, so the children she had with Jefferson were 1/8 black. They were absorbed by white society. They were not non-persons. In those days, the US wasn’t as rigid about color as it became in the 20th century. The first law stating that even one drop of black blood would make a person legally black was passed by Virginia in the 1920’s.

Regards. James

Bill, I read the article that you are focusing on here …. and I was also alarmed by it being portrayed as “Progressive”

Thanks for the detailed explanation ….

I posted a response in the comments section admonishing it as being from a “Progressive Think Tank” and about the article reinforcing discredited Neo Liberal Ideology and that the entire notion of of Government “Debt/Deficit” etc it is really just Wedge Politics masquerading as Economics …..

UK’s new prime minister is talking about class quite a lot.

Declaring her party the party of working people.

Tied to faith in free market forces even a little fiscal loosening will not

achieve any reversal of growing inequality and falling social mobility.

Chief austerian chancellor Osbourne embraced ‘the living wage’

Orwellian indeed but maybe there is some cognitive dissonance thrown in.

Mahaish:

“…so the government wasn’t pushing anything anywhere,…,”

I’m not sure you are right there. Peter Costello’s budgets changed the tax on CGT, allowing 50 % discount after just one year’s ownership, leading to the rush for “investment properties” and the housing bubble, which we are faced with today. This helped lift private sector debt to the levels you mention, and allowed all that hype about “surplus budgets” and “budget repair”, which we are suffering from even today.

I’m a Guardian reader and subscriber. It has been very frustrating over the past months having to read the anti-Corbyn bias in so many featured articles (with some honourable exceptions). With his second leadership election victory, they have had to change their line somewhat, but we still get the likes of Polly Toynbee (ex-SDP member, then Blairite) sniping away.

.

Larry Elliot (economics editor) writes some good pieces, and was pro-Brexit and referred to the “dying Eurozone”. I don’t know if he “gets” MMT, but I would not have thought of him as neo-liberal. However, I suppose the paper’s overall stance on the deficit is pretty mainstream, and I think they went along with pre-Corbyn Labour’s “austerity lite” approach.

.

The Guardian is the best of a very bad bunch, even if I find myself disagreeing with well over 50% of what it usually says about important issues. I actually read it mostly for Doonesbury, John Crace’s political sketches, the letters page (occasionally dissenting views are published), and occasional articles by the likes of Paul Mason (bit of a loose cannon), and George Monbiot on a good day, Owen Jones, and some others.

.

I hadn’t known much about the Guardian’s history, other than it having been “The Manchester Guardian”, so thanks for the instructive blog post Bill.

.

fair call totarum,

the governments policy settings indeed played a role.

but I think the play book for the banks meant , that the debt blowout would have happened anyway given the prevailing greenspanian mantra, that the financial markets were liquid enough to know best about risk, and the central banks inability to control the money supply except through a very inexact pricing mechanism, which meant most of the time they were reacting defensively to market behaviour.

we all know now that this was all a load of cobblers, and no doubt we are going to re visit this issue in the next 10 years me thinks.

mahaish

$70Bn in assets sales

Howard only had a handful of surpluses and very average balance of trade.

The dollars to pay off govt debt via the surplus method have to come from either the private sector or the foreign sector….