Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – July 30-31, 2016 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Modern Monetary Theory accepts that continually expanding the money supply will inevitably be inflationary.

The answer is False.

The question requires you to: (a) understand the difference between bank reserves and the money supply; and (b) understand the Quantity Theory of Money.

The mainstream macroeconomics text book argument that increasing the money supply will cause inflation is based on the Quatity Theory of Money. First, expanding bank reserves will put more base money into the economy but not increase the aggregates that drive the alleged causality in the Quantity Theory of Money – that is, the various estimates of the “money supply”.

Second, even if the money supply is increasing, the economy may still adjust to that via output and income increases up to full capacity. Over time, as investment expands the productive capacity of the economy, aggregate demand growth can support the utilisation of that increased capacity without there being inflation.

In this situation, an increasing money supply (which is really not a very useful aggregate at all) which signals expanding credit will not be inflationary.

It is possible that if nominal demand kept increasing beyond the capacity of the real economy to absorb it via increased production, then inflation results and the ‘value’ of the dollar would start to decline. But this outcome is not inevitable, so the answer is False.

The Quantity Theory of Money which in symbols is MV = PQ but means that the money stock times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and Q is always at full employment as a result of market adjustments.

In applying this theory the mainstream deny the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will react to the increased nominal demand by increasing output.

The mainstream have related the current non-standard monetary policy efforts – the so-called quantitative easing – to the Quantity Theory of Money and predicted hyperinflation will arise.

So it is the modern belief in the Quantity Theory of Money is behind the hysteria about the level of bank reserves at present – it has to be inflationary they say because there is all this money lying around and it will flood the economy.

Textbook like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted hometo the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. We have regularly traversed this point. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

So when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt. So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves. So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

For the monetary aggregates (outside of base money) to increase, the banks would then have to increase their lending and create deposits. This is at the heart of the mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. The recent experience (and that of Japan in 2001) showed that quantitative easing does not succeed in doing this.

This should come as no surprise at all if you understand Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Those that claim that quantitative easing will expose the economy to uncontrollable inflation are just harking back to the old and flawed Quantity Theory of Money. This theory has no application in a modern monetary economy and proponents of it have to explain why economies with huge excess capacity to produce (idle capital and high proportions of unused labour) cannot expand production when the orders for goods and services increase. Should quantitative easing actually stimulate spending then the depressed economies will likely respond by increasing output not prices.

So the fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation does not provide a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money because it has not impacted on the monetary aggregates.

The fact that is hasn’t is not surprising if you understand how the monetary system operates but it has certainly bedazzled the mainstream economists.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

If there is an external deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and the government balances its fiscal outcome then the private sector will have an excess of spending relative to its income equal to 2 per cent of GDP.

The correct answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government fiscal balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

(1) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all tax revenue minus total transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total net taxes (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

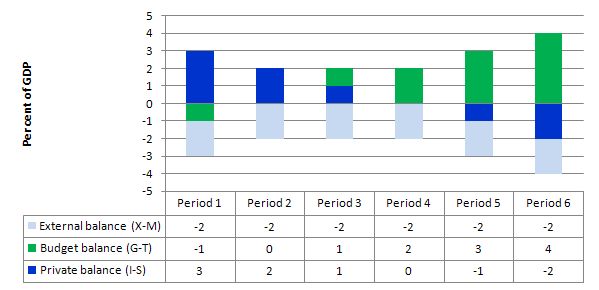

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP.

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a fiscal surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government fiscal outcome enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

So this is the situation described in the Question which means that the private sector is running an overall deficit – so incurring an “excess of spending over its income overall equal to 2 per cent of GDP”.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terorists typically overlook – that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public fiscal outcome then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its “excess expenditure”. That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a fiscal outcome with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

In Periods 3 and 4, the fiscal deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of fiscal deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government fiscal deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 3:

A national government would be unable to rely on the central bank purchasing treasury debt to match its fiscal deficit if the central bank is targeting a positive short-term policy rate.

The answer is False.

The central bank conducts what are called liquidity management operations for two reasons. First, it has to ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. Second, it must maintain aggregate bank reserves at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on “excess” reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Commercial banks maintain accounts with the central bank which permit reserves to be managed and also the clearing system to operate smoothly. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also can set a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank (which might be zero).

Many countries (such as Australia, Canada and zones such as the European Monetary Union) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like Japan and the US have typically not offered a return on reserves until the onset of the current crisis.

If the support rate is zero then persistent excess liquidity in the cash system (excess reserves) will instigate dynamic forces which would drive the short-term interest rate to zero unless the government sells bonds (or raises taxes). This support rate becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy.

The short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

In most nations, commercial banks by law have to maintain positive reserve balances at the central bank, accumulated over some specified period. At the end of each day commercial banks have to appraise the status of their reserve accounts. Those that are in deficit can borrow the required funds from the central bank at the discount rate.

Alternatively banks with excess reserves are faced with earning the support rate which is below the current market rate of interest on overnight funds if they do nothing. Clearly it is profitable for banks with excess funds to lend to banks with deficits at market rates. Competition between banks with excess reserves for custom puts downward pressure on the short-term interest rate (overnight funds rate) and depending on the state of overall liquidity may drive the interbank rate down below the operational target interest rate. When the system is in surplus overall this competition would drive the rate down to the support rate.

The main instrument of this liquidity management is through open market operations, that is, buying and selling government debt. When the competitive pressures in the overnight funds market drives the interbank rate below the desired target rate, the central bank drains liquidity by selling government debt. This open market intervention therefore will result in a higher value for the overnight rate. Importantly, we characterise the debt-issuance as a monetary policy operation designed to provide interest-rate maintenance. This is in stark contrast to orthodox theory which asserts that debt-issuance is an aspect of fiscal policy and is required to finance deficit spending.

So the fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

Accordingly, debt is issued as an interest-maintenance strategy by the central bank. It has no correspondence with any need to fund government spending. Debt might also be issued if the government wants the private sector to have less purchasing power.

Further, the idea that governments would simply get the central bank to “monetise” treasury debt (which is seen orthodox economists as the alternative “financing” method for government spending) is highly misleading. Debt monetisation is usually referred to as a process whereby the central bank buys government bonds directly from the treasury.

In other words, the federal government borrows money from the central bank rather than the public. Debt monetisation is the process usually implied when a government is said to be printing money. Debt monetisation, all else equal, is said to increase the money supply and can lead to severe inflation.

However, as long as the central bank has a mandate to maintain a target short-term interest rate, the size of its purchases and sales of government debt are not discretionary. Once the central bank sets a short-term interest rate target, its portfolio of government securities changes only because of the transactions that are required to support the target interest rate.

The central bank’s lack of control over the quantity of reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetisation. The central bank is unable to monetise the federal debt by purchasing government securities at will because to do so would cause the short-term target rate to fall to zero or to the support rate. If the central bank purchased securities directly from the treasury and the treasury then spent the money, its expenditures would be excess reserves in the banking system. The central bank would be forced to sell an equal amount of securities to support the target interest rate.

The central bank would act only as an intermediary. The central bank would be buying securities from the treasury and selling them to the public. No monetisation would occur.

However, the central bank may agree to pay the short-term interest rate to banks who hold excess overnight reserves. This would eliminate the need by the commercial banks to access the interbank market to get rid of any excess reserves and would allow the central bank to maintain its target interest rate without issuing debt.

In these cases, it could buy all the treasury debt without consequences for its policy target.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The consolidated government – treasury and central bank

- Saturday Quiz – May 1, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

“The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.”

well QE was a response to the GFC which was a funding crisis;by flooding the markets with reserves;cost of funds went down and banks could stabilise….still ultimately be zombie banks.QE wasnt neccessarily about spurring lending.But about filling the funding gap that many institutions faced as the cost of funds skyrocketed/more collateral was required in the money markets.