Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian labour market – the dismal picture unfolds further

Last month, employment growth was basically flat (slightly negative). Participation decreased. The signs were ominous. This month, the dismal picture unfolded further. Today’s release of the – Labour Force data – for February 2016 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that those ominous signs have worsened. Total employment growth was zero (well 300 net jobs). A pathetic result. Unemployment fell but only because the participation rate fell by 0.2 points – thus the idle labour arising from the weak employment growth just left the labour force and is now hidden unemployment. Working hours fell further – the trend is flat and has been for the last few years. The teenage labour market continued to deteriorate with the adjusted unemployment rate (taking into account the sharp fall in participation since the downturn) of 29.1 per cent rather than the official estimate for February 2016 of 17.8 per cent. Overall, with private investment forecast to decline further over the next 12 months, the Australian labour market is looking very weak and the Federal government should be introducing a rather sizeable fiscal stimulus in its upcoming fiscal statement. This should include large-scale public sector job creation which would ensure teenagers regained the jobs that have been lost due to the fiscal drag over the last several years.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for February 2016 are:

- Employment increased 300 (0 per cent) with full-time employment increasing by 15,900 and part-time employment decreasing by 15,600.

- Unemployment decreased by 27,300 to 732,600.

- The official unemployment rate decreased by 0.2 percentage points to 5.8 per cent but only because the participation rate fell sharply. Hidden unemployment thus rose.

- The participation rate declined by 0.2 points to 64.9 per cent. This is well below its November 2010 peak (recent) of 65.8 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked decreased 2 million hours (-0.12 per cent).

- The quarterly ABS broad labour underutilisation estimates (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) were updated in this release for the February quarter. Underemployment was at 8.4 per cent and total labour underutilisation rate was at 14.2 per cent. There were 1,051.2 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1.839.3 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed. The next quarterly release will be in the February 2016 publication released in early March.

Employment growth – non-existent

In February, the total (net) employment change was 300 jobs following two second consecutive month of negative growth.

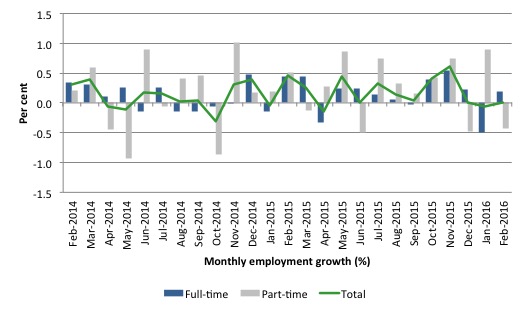

The zig-zag pattern that we have observed over the last 24 months or so – where the employment estimates have been switching back and forth regularly between negative employment growth and positive growth with the occasional spikes – continues.

Full-time employment Rose increased 15,900, while part-time employment decreased 15,600.

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to February 2016 using seasonally adjusted data.

It gives you a good impression of just how flat employment growth has been over the last 2 years.

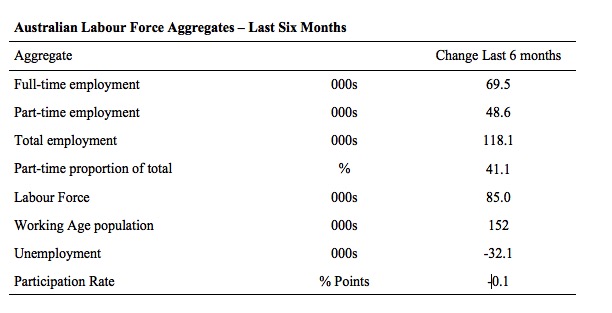

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months. The monthly data is highly variable so this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends. WAP is working age population (above 15 year olds).

The conclusion – overall there have been 118.1thousand jobs (net) added in Australia over the last six months while the labour force has increased by only 85 thousand. Employment growth has thus outstripped the increase in the supply of labour with the result that unemployment has fallen by 32.1 thousand.

This should not be taken as an indication of strong employment growth. Rather, the weak participation has meant the labour force growth rate has slowed significantly.

Full-time employment has risen by 69.5 thousand jobs (net) while part-time work has risen by 48.6 thousand jobs. Thus, 41.1 per cent of the total employment created (net) over the last 6 months has been part-time.

The participation rate has fallen by 0.1 points and remains at depressed levels.

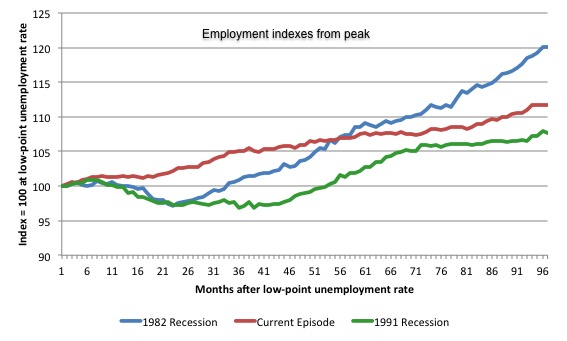

The following graph shows employment indexes for the last 3 recessions and allows us to see how the trajectory of total employment after each peak prior to the three major recessions in recent history: 1982, 1991 and 2009 (the latter to capture the current episode).

The peak is defined as the month of the low-point unemployment rate in the relevant cycle and total employment was indexed at 100 in each case and then indexed to that base for each of the months as the recession unfolded.

I have plotted the 3 episodes for 96 months after the low-point unemployment rate was reached in each cycle – the length of the current cycle.

The initial employment decline was similar for the 1982 and 1991 recessions but the 1991 recovery was delayed by many months and the return to growth much slower than the 1982 recession.

The current episode is distinguished by the lack of a major slump in total employment, which reflects the success of the large fiscal stimulus in 2008 and 2009.

However, the recovery spawned by the stimulus clearly dissipated once the fiscal position was reversed and the economy fell back into producing very subdued employment outcomes.

While the employment growth was stronger in October and November 2015 we now know that the estimates were distorted by the rotational issues in the sample used by the ABS as well as other issues relating to survey reliability over that period.

Moreover, since February 2008, employment has grown by a miserly 11.7 per cent, which is a very slow pace in historical terms for such a long period.

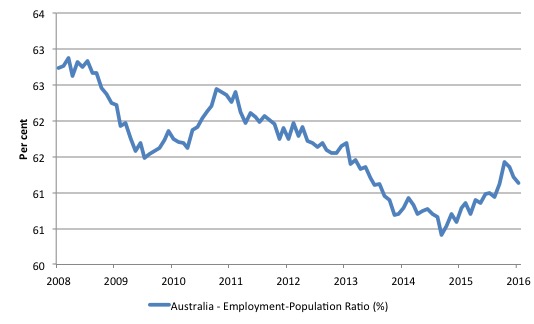

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since February 2008 (the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

It dived with the onset of the GFC, recovered under the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus packages but then went backwards again as the last Federal government imposed fiscal austerity in a hare-brained attempt at achieving a fiscal surplus.

The ratio began rising in October 2014 which suggested to some that the labour market had bottomed out and would improve slowly as long as there are no major policy contractions or cuts in private capital formation.

However, the peak in November is gone (partly distorted by the sample survey issues) and the ratio is once again in retreat.

The on-going fiscal deficit is still supporting growth in the economy as the spending associated with the mining boom disappears.

The series decreased by 0.1 points in February and is now 0.3 points below the December 2015 reading.

Teenage labour market – continues to deteriorate

The teenage labour market deteriorated further in February 2016 with full-time employment falling by 5.4 thousand and part-time employment rising by just 500 net jobs.

Total employment thus fell by 4.9 thousand (net).

The teenage unemployment rate fell by by 0.5 points to 17.8 per cent in February 2016 but it was all down to a large drop in the participation rate (0.7 points), presumably part of which is due to teenagers going back to school as a result of inadequate job opportunities.

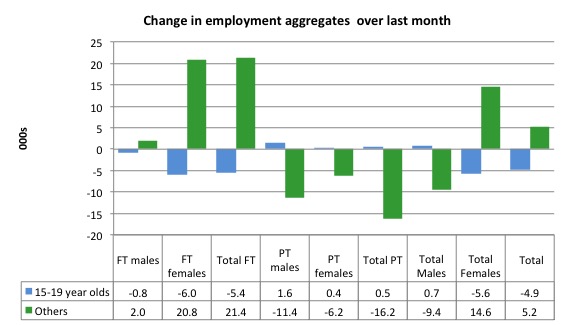

The following graph shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest)

If you take a longer view you see how poor the situation remains.

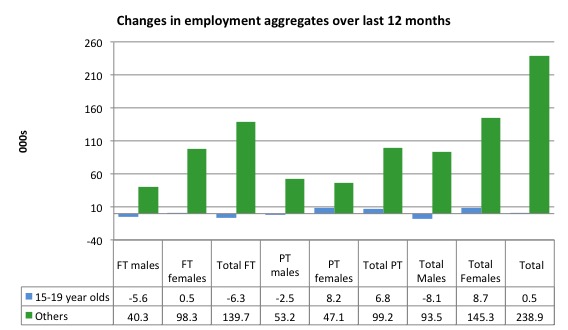

Over the last 12 months, teenagers have gained only 500 (net) jobs overall while the rest of the labour force have gained 238.9 thousand net jobs. Remember that the overall result represents a fairly poor annual growth in employment.

The teenage segment of the labour market is being particularly dragged down by the sluggish employment growth, which is hardly surprising given that the least experienced and/or most disadvantaged (those with disabilities etc) are rationed to the back of the queue by the employers.

The following graph shows the change in aggregates over the last 12 months. It is as if the teenagers have not had a stake in the labour market either way (blue bars barely visible).

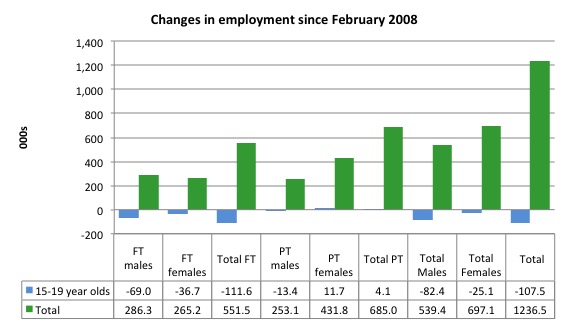

To further emphasise the plight of our teenagers, I compiled the following graph that extends the time period from the February 2008, which was the month when the unemployment rate was at its low point in the last cycle, to the present month (February 2016). So it includes the period of downturn and then the so-called “recovery” period. Note the change in vertical scale compared to the previous two graphs.

Since February 2008, there have been only 1,236 thousand (net) jobs added to the Australian economy but teenagers have lost a staggering 107.5 thousand over the same period. It is even more stark when you consider that 111.6 thousand full-time teenager jobs have been lost in net terms.

Even in the traditionally, concentrated teenage segment – part-time employment, teenagers have gained only 4.1 thousand jobs (net) even though 685 thousand part-time jobs have been added overall.

Overall, the total employment increase is modest. Further, around 55 per cent of the total (net) jobs added since February 2008 have been part-time, which raises questions about the quality of work that is being generated overall.

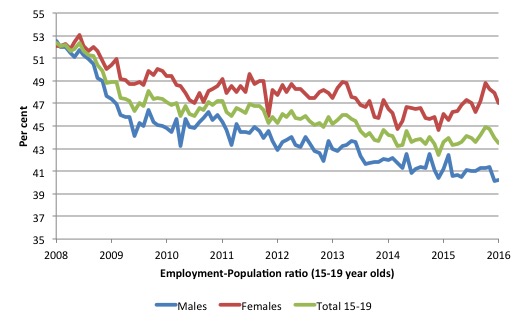

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since February 2008 (the month which coincided with the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The facts are that the absolute loss of jobs reported above is depicting a disastrous situation for our teenagers. Males, in particular, have lost out severely as a result of the economy being deliberately stifled by austerity policy positions.

In the last month, with the employment situation improving, there has been some reversal in the downward trends in these ratios.

The male ratio has fallen by 12.3 percentage points since February 2008, the female ratio has fallen by 5.1 percentage points and the overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 8.8 percentage points. That is a substantial decline in the employment market for Australian teenagers.

The other staggering statistic relating to the teenage labour market is the decline in the participation rate since the beginning of 2008 when it peaked in January at 61.4 per cent. In February 2016, the participation rate was just 53 per cent.

That is an additional 124.1 thousand teenagers who have dropped out of the labour force as a result of the weak conditions since the crisis.

If we added them back into the labour force the teenage unemployment rate would be 29.1 per cent rather than the official estimate for February 2016 of 17.8 per cent. Some may have decided to return to full-time education and abandoned their plans to work. But the data suggests the official unemployment rate is significantly understating the actual situation that teenagers face in the Australian labour market.

Overall, the performance of the teenage labour market remains poor. It doesn’t rate much priority in the policy debate, which is surprising given that this is our future workforce in an ageing population. Future productivity growth will determine whether the ageing population enjoys a higher standard of living than now or goes backwards.

I continue to recommend that the Australian government immediately announce a major public sector job creation program aimed at employing all the unemployed 15-19 year olds, who are not in full-time education or a credible apprenticeship program.

Unemployment decreased by 27,300 to 732,600

With unemployment decreasing by 27,300 to 732,600, the official unemployment rate fell by 0.2 percentage points to 5.8 per cent in February 2016.

But don’t be fooled into thinking this is an improvement. The decline (see below) is all due to the drop in the participation rate – that is, workers dropping out of the labour force as a result of lack of employment opportunities.

Overall, the labour market still has significant excess capacity available in most areas and what growth there is is not making any major inroads into the idle pools of labour.

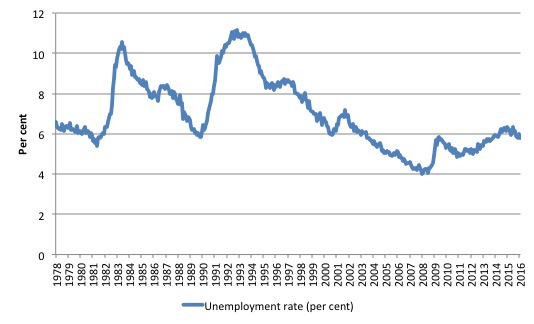

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from February 1978 to February 2016. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

After falling steadily as the fiscal stimulus pushed growth along, the unemployment rate slowly trended up for some months.

It is now above the peak that was reached just before the introduction of the fiscal stimulus. In other words, the gains that emerged in the recovery as a result of the fiscal stimulus in 2009-10 have now been lost.

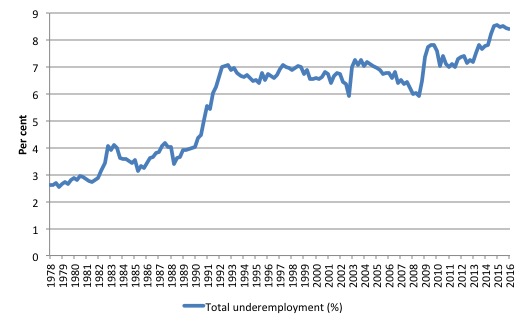

Broad labour underutilisation – upwards of 14.2 per cent

The ABS published its quarterly broad labour underutilisation measures for the February-quarter in this month’s data release.

In the February-quarter, total underemployment was 8.4 per cent and the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate (the sum of unemployment and underemployment) was 14.2 per cent.

There were 1,058.9 thousand persons underemployed and a total of 1,791.5 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

The following graph plots the history of underemployment in Australia since February 1978 to the February-quarter 2015.

If hidden unemployment is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate well above 16 per cent at present. Please read my blog – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

The next update will be for the May-quarter 2016 and will be published published in the June 2016 Labour Force release.

Aggregate participation rate – fell sharply by 0.2 percentage points

The February 2016 participation rate fell sharply by 0.2 percentage points to be 64.9 per cent. It remains substantially down on the most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.8 per cent when the labour market was still recovering courtesy of the fiscal stimulus.

The fact that unemployment fell this month is all due to the decline in the labour force as a result of the drop in participation.

The labour force is a subset of the working-age population (those above 15 years old). The proportion of the working-age population that constitutes the labour force is called the labour force participation rate. Thus changes in the labour force can impact on the official unemployment rate, and, as a result, movements in the latter need to be interpreted carefully. A rising unemployment rate may not indicate a recessing economy.

The labour force can expand as a result of general population growth and/or increases in the labour force participation rates.

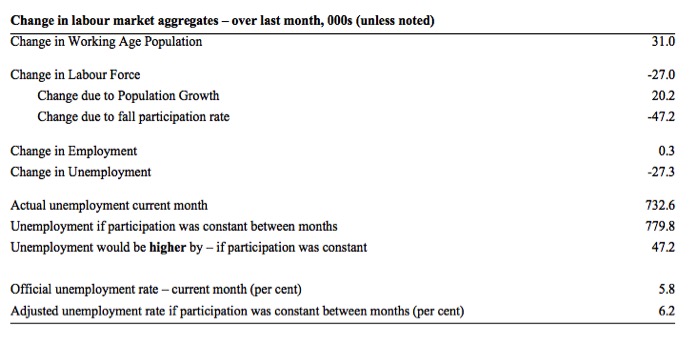

What would have the unemployment rate been had the participation rate not fallen by 0.2 points?

The following Table shows the breakdown in the changes to the main aggregates (Labour Force, Employment and Unemployment) and the impact of the rise in the participation rate.

In February 2016, the rise in employment of 300 (net) jobs was accompanied by a labour force decline of 27 thousand. As a result, unemployment decreased by 27.3 thousand.

The declining labour force in February 2016 was the outcome of two separate factors:

- The underlying population growth added 20.2 thousand persons to the labour force. The population growth impact on the labour force aggregate is relatively steady from month to month but has slowed in recent months; and

- The fall in the participation rate meant that there were 47.2 thousand workers dropping out of the labour force (relative to what would have occurred had the participation rate remained unchanged).

- The net result was the decline in the labour force of 27 thousand (rounded).

The fall in the participation meant that unemployment fell – but this is a time when a declining unemployment rate signals weakness rather than strength.

If the participation rate had not have fallen, total unemployment, at the current employment level, would have been 779.8 thousand rather than the official count of 732.6 thousand as recorded by the ABS – a difference of 47.2 thousand workers (the ‘participation effect’).

Thus, without the fall in the participation rate, the unemployment rate would have been 6.2 per cent (rounded) rather than its current value of 5.8 per cent.

The conclusion is that hidden unemployment rose significantly in February 2016 while official unemployment rate fell by 0.2 points.

There is considerable monthly fluctuation in the participation rate but the current rate of 64.9 per cent is a long way below its most recent peak in November 2010 of 65.8 per cent.

What would the unemployment rate be if the participation rate was at that last November 2010 peak level (65.8 per cent)?

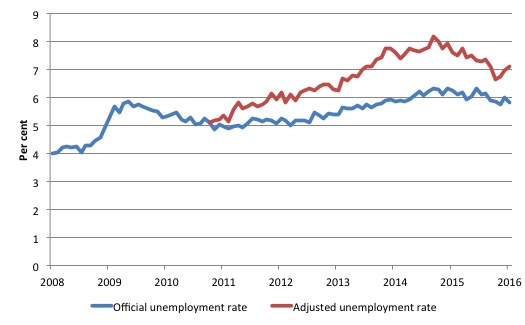

The following graph tells us what would have happened if the participation rate had been constant over the period November 2010 to February 2016. The blue line is the official unemployment since its most recent low-point of 4 per cent in February 2008.

The red line starts at November 2010 (the peak participation month). It is computed by adding the workers that left the labour force as employment growth faltered (and the participation rate fell) back into the labour force and assuming they would have been unemployed. At present, this cohort is likely to comprise a component of the hidden unemployed (or discouraged workers).

Total official unemployment in February 2016 was estimated to be 732.6 thousand. However, if participation had not have fallen relative to November 2010, there would be 907.2 thousand workers unemployed given growth in population and employment since November 2010.

The unemployment rate would now be 7.1 per cent if the participation had not fallen below its November 2010 peak of 65.8 per cent. The official unemployment in February 2016 was 5.8 per cent.

The difference between the two numbers mostly reflects, the change in hidden unemployment (discouraged workers) since November 2010. These workers would take a job immediately if offered one but have given up looking because there are not enough jobs and as a consequence the ABS classifies them as being Not in the Labour Force.

There has been some change in the age composition of the labour force (older workers with low participation rates becoming a higher proportion) but this only accounts for about a 1/3 of the shift. The rest is undoubtedly accounted for by the rise in hidden unemployment.

Note, the gap between the blue and red lines doesn’t sum to total hidden unemployment unless November 2010 was a full employment peak, which it clearly was not. The interpretation of the gap is that it shows the extra hidden unemployed since that time.

In recent months, this gap has shrunk as participation has risen.

Hours worked – fell in February 2016

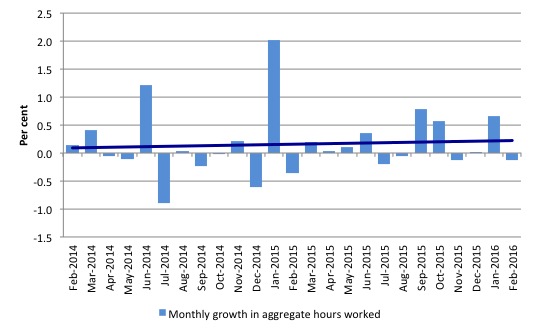

Aggregate monthly hours fell by 2 million hours (-0.12 per cent) in February 2016 in seasonally adjusted terms.

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months. The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts as close to a zero trend as you can get (especially given the outlying spike in January 2015).

You can see the pattern of the change in working hours is also portrayed in the employment graph – zig-zagging across the zero growth line.

Conclusion

I always repeat my monthly warning – we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

Today’s figures show that employment growth continues to zig-zag across the zero growth line. Only 300 (net) jobs were created in Australia in February 2016 – a dismal outcome indeed.

The conclusion is that the situation is rather weak on the demand for labour side.

Unemployment fell this month solely due to the decline in labour force participation, which means the idle labour as a result of the weak employment growth is just sitting outside the labour force as hidden unemployment rather than being counted among the official unemployed.

The teenage labour market remains in a parlous state and it deteriorated further this month.

I consider this situation to warrant immediate attention by the Federal Government. The neglect of our teenagers will have a very long memory indeed and the negative consequences will be stronger given the ageing population.

The Federal government appears incapable of addressing this dire issue.

FINALLY – Introductory Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) Textbook

I will write a separate blog about this presently, but today we finally published the first version of our MMT textbook – Modern Monetary Theory and Practice: an Introductory Text – today (March 10, 2016).

The long-awaited book is authored by myself, Randy Wray and Martin Watts.

It is available for purchase at:

1. Amazon.com (60 US dollars)

2. Amazon.co.uk (£42.00)

3. Amazon Europe Portal (€58.85)

4. Create Space Portal (60 US dollars)

By way of explanation, this edition contains 15 Chapters and is designed as an introductory textbook for university-level macroeconomics students.

It is based on the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and includes the following detailed chapters:

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: How to Think and Do Macroeconomics

Chapter 3: A Brief Overview of the Economic History and the Rise of Capitalism

Chapter 4: The System of National Income and Product Accounts

Chapter 5: Sectoral Accounting and the Flow of Funds

Chapter 6: Introduction to Sovereign Currency: The Government and its Money

Chapter 7: The Real Expenditure Model

Chapter 8: Introduction to Aggregate Supply

Chapter 9: Labour Market Concepts and Measurement

Chapter 10: Money and Banking

Chapter 11: Unemployment and Inflation

Chapter 12: Full Employment Policy

Chapter 13: Introduction to Monetary and Fiscal Policy Operations

Chapter 14: Fiscal Policy in Sovereign nations

Chapter 15: Monetary Policy in Sovereign Nations

It is intended as an introductory course in macroeconomics and the narrative is accessible to students of all backgrounds. All mathematical and advanced material appears in separate Appendices.

A Kindle version will be available the week after next.

Note: We are soon to finalise a sister edition, which will cover both the introductory and intermediate years of university-level macroeconomics (first and second years of study).

The sister edition will contain an additional 10 Chapters and include a lot more advanced material as well as the same material presented in this Introductory text.

We expect the expanded version to be available around June or July 2016.

So when considering whether you want to purchase this book you might want to consider how much knowledge you desire. The current book, released today, covers a very detailed introductory macroeconomics course based on MMT.

It will provide a very thorough grounding for anyone who desires a comprehensive introduction to the field of study.

The next expanded edition will introduce advanced topics and more detailed analysis of the topics already presented in the introductory book.

Weekend Quiz

The Weekend Quiz (formerly known as the Saturday Quiz) will be back again tomorrow. It will be of an appropriate order of difficulty (-:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Who wouldn’t be dropping out of this clusterfuck? If I was still in the labour market I would probably be seriously considering giving it all a big miss.

At 68 I’m past that,thankfully. As Eric Bogle (an expatriate Scot) has so aptly written and sung,”it’s all over now and I’m easy”.

Bill, I was hoping you’d have something to say about Shorten’s comments focusing on full employment. The policy details seem to be inadequate, but it’s the first time I’ve heard any political leader list full employment (by any definition) as a top priority during my lifetime, and I can’t help hoping that it represents at least the beginning of a change in policy approach.

himi,

In the UK David Cameron has mentioned it in speeches, but most people assume it is just rhetoric, as the OBR which actually determines these things seem to be assuming 5% unemployment is full capacity.

Kind Regards

himi,

I thought the same. Has Shorten and the Labor party finally seen a point of difference between it and the Givernment which ought to resonate with voters? Perhaps, especially as the portends do not look good without fiscal intervention or the almost useless and even counter productive use of interest rates.

If he fleshes out this vague policy he will face attacks of “where is the money going to come from” and “the budget deficit is too high” etc etc.

I doubt if Labor understands federal fiscal capacity and even if it does I doubt it’s ability to persuade voters that government cries of irresponsible spending are just nonsense.

Barri, all Labor needs to do is make a statement they are prioritising full employment over the budget balance, and deflect all the questions about costs with a snappy slogan. Like ‘Ockers before Economists’ or something.

Cameron talking about full employment is obviously bullsh*t, given his political affiliations. Shorten is at least from a party that’s closely tied to organised labour, meaning he’s not going against fundamental principles of his party . . .

If Labor sticks with this as one of their policies going into the election it might be a good time for someone like Bill to start making more noise about a job guarantee as a way to implement that policy. Even if it doesn’t end up being taken seriously in Canberra it does provide a platform for getting the idea more attention. Certainly a bigger platform than comments on Facebook and newspaper articles and the like, which is about all I’ve managed so far.

Bill,

Is the MMT Text available in Australia or do we have to order it online ?

@Mathew B. Yes that might work, or not! Certainly the government under MT has toned down the previous and unlamented Abbott regime’s (not worthy of the honorific of “government”) and there have been hints that the forthcoming budget will feature infrastructure spending.

RE Barri Mundee says:

Friday, March 18, 2016 at 7:39 himi,

Bill Shorten on 7.30 report (ABC talk show) was asked the question and responded sheepishly 5% and no mention of underemployment being some number or %.

Dear Alan Dunn (at 2016/03/18 at 11:39)

It is only available on-line at this stage. The next extended version will be available in bookshops later in the year.

best wishes

bill

Big historic upset for the Tory government in the UK. The man in charge of the terrible “reforms” to social security has resigned. Here is his letter of resignation, look at the last 3 paragraphs, and those bits in bold:

This will be a very big deal in the UK.

Kind Regards