I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The government really is instrumental in creating growth

Sometimes one reads a press article that is so obviously misleading that it is hard to know where to start with it. But perhaps the conclusion is the best place to start sometimes. Such is the case of a Bloomberg article (January 15, 2016) – What #ResistCapitalism Gets Wrong – written by American academic Noah Smith. Basically, the article attempts to attribute all of the post-Second World War prosperity to the “free market economy”, which he says is “a term many use synonymously with ‘capitalism'”. By the end of the article we learn that in fact that prosperity does not come from ‘free market’ liberalisation and that strong governments are essential for growth and reductions in inequality. The “boring old mixed economy” where, in Noah Smith’s words “government really is instrumental in creating growth”. Start with the conclusion and read backwards is my advice in this case.

The argument presented by Noah Smith is that “leftist” movements including “the rhetoric of politicians like presidential candidate Bernie Sanders — who proudly declares himself a “democratic socialist” — has revived general interest in the question of which economic system is best.”

He claims that “fall of the Soviet Union and the successful economic liberalizations in China and India would have ended the debate over whether capitalism is the best economic system.”

And he claims that the “support for a ‘free market economy’ … remains high in almost all countries and regions of the globe”.

Note here the use of the term ‘free market economy’ and Smith’s selective quoting of an October 2014 Pew Research Center report – Emerging and Developing Economies Much More Optimistic than Rich Countries about the Future.

The Pew Research Center is touted as an independent, non-partisan think tank but the specific question that Smith refers to is framed in such a way that the results are biased to the outcome that occurred.

The question (13a) was (Source):

Please tell me whether you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statements: a. Most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people are rich and some are poor.

My response to the person conducting the telephone questionnaire would have been, initially, please define a “free market economy”.

You can see the tension in surveys like this in terms of demarcating terms and concepts in some later questions and responses.

For example question 23c asks about “The gap between the rich and the poor” and “A global median of 60% so the gap between the rich and poor is a very big problem in their country”.

When asked to articulate what was to blame for this increasing gap (Q77) the largest cause was that government policies had failed to deal with the problem, although, once again, ambiguity reigns supreme because the survey isn’t specific here.

However, some hint is provided in Q77b, which asks whether the respondent would prefer “high taxes to fund programs for poor” or “low taxes to encourage investment and growth”.

Here, we encounter the framing problem again. There is no stronger empirical evidence to support the notion that lower taxes encourage private capital formation, other things equal. Further, the claim that higher taxes are needed to fund programs for the poor, as if, that is the way in which more equitable government spending can only occur is also a biased and technically incorrect proposition.

Further, the way in which PEW reported their results is also biased. When discussing this particular question and response, we encounter a headline “Many Say Low Taxes Are the Answer”, which is not representative of the results obtained.

Taken at face value, though, with the median response much higher in favour of the increased tax option, one wonders what the respondents think a ‘free market economy’ actually is, where they also want strong government action to reduce the disturbing rise in inequality between rich and poor.

And, how does Noah Smith reconcile these loaded PEW survey questions with the results of academic research by political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page published in September 2014 by the American Political Science Association in their journal Perspectives on Politics?

This study built on earlier research by Benjamin Page, Larry Bartels and Jason Seawright, published in March 2013

[References:

Page, B.I., Bartels, L. and Seawright, J. (2013) ‘Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealthy Americans’, Perspectives on Politics, 11(1), 51-73.

Gilens, M. and Page, B.I. (2014) ‘Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizen’, Perspectives on Politics, 12(03), 564-581.]

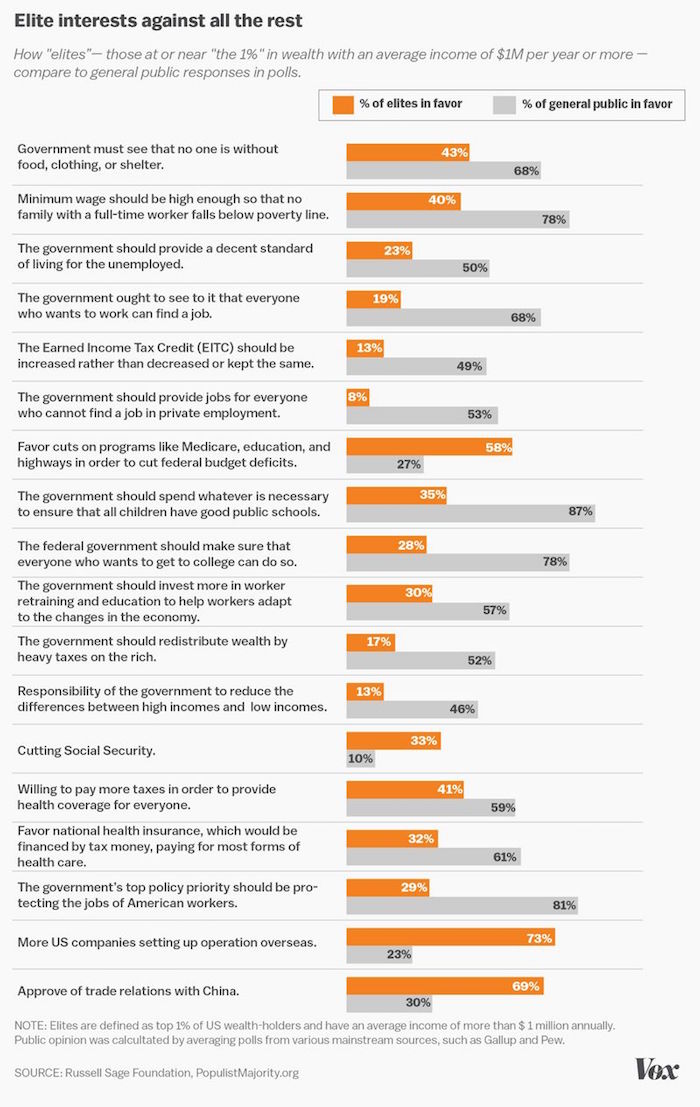

The earlier research demonstrated the vastly different policy preferences held by high income Americans (in this case the top 1 per cent of the income distribution) relative to the general public.

The research was motivated by the observation that the “wealthy exert more political influence than the less affluent do” and so if their preferences were not representative of American society in general then that would be “troubling for democratic policy making”.

The authors find that the high income earners in the US are not only very active politically but hold ultra conservative views “concerning taxation, economic regulation, and especially social welfare programs” that are not remotely shared by the general public.

The 2014 research paper concluded that:

… economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.

So much for the ‘free market economy’!

In June 2014, the unlikely sounding – Campaign for America’s Future – which is, in its own words, “the strategy center for the progressive movement”, collated the academic results and compared them to previous opinion polls in a Memo – The American Majority Is A Populist Majority.

Their opening statement was:

Of all the myths that circulate in Washington, perhaps none is more prevalent or intractable than the one that says that the United States is a center-right nation – and that majority public opinion lies somewhere between the views of conservative Democrats and those of less extreme Republicans.

However, they conclude that “Poll after poll shows that a majority of Americans hold populist opinions on a broad range of economic and political issues-opinions that are often far removed from positions held by elites”, although the mainstream media really only pumps out the elite view.

The organisation Vox Media recently (June 16, 2015) brought together this research in one of their ‘Explainers’ – Rich people are jerks, explained. The graphic they produced by way of summary (reproduced below) is worth considering.

So much for the ‘free market economy’, which seems to have a very active government sector, which the vast majority of people consider to be essential.

Noah Smith rides over all this reality and continues the misleading narrative.

He posits:

There is good reason for capitalism’s widespread support. The past quarter-century has seen an enormous increase in the standard of living of people in poor and developing countries. Inequality has fallen as countries in Asia, Africa and elsewhere have closed some of the gap with rich countries. The number of people living in extreme poverty has plunged, even as the world’s population has continued to climb. As a result, far fewer human beings are going hungry.

He probably should have read Dani Rodrik’s latest article (January 13, 2015) – The Return of Public Investment – before making these claims.

Rodrik begins:

The idea that public investment in infrastructure – roads, dams, power plants, and so forth – is an indispensable driver of economic growth has always held powerful sway over the minds of policymakers in poor countries … it motivates the new China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which aims to fill the region’s supposed $8 trillion infrastructure gap.

He notes that that “this kind of public-investment-driven growth model – often derisively called “capital fundamentalism” – has long been out of fashion among development experts. Since the 1970s, economists have been advising policymakers to de-emphasize the public sector” and deregulate etc.

But he argues that:

If one looks at the countries that, despite strengthening global economic headwinds, are still growing very rapidly, one will find public investment is doing a lot of the work.

He then discusses some case studies including Ethiopian which “is the most astounding success story of the last decade … significant poverty reduction and improved health outcomes … is resource poor and did not benefit from commodity booms … Nor did economic liberalization and structural reforms of the type typically recommended by the World Bank and other donors play much of a role”.

So, how did Ethiopian achieve such a result?

Rodrik writes:

Rapid growth was the result, instead, of a massive increase in public investment, from 5% of GDP in the early 1990s to 19% in 2011 – the third highest rate in the world. The Ethiopian government went on a spending spree, building roads, railways, power plants, and an agricultural extension system that significantly enhanced productivity in rural areas, where most of the poor reside.

He then describe similar public infrastructure driven growth in India and Bolivia as examples for advanced countries “that stand to gain the most from ramping up domestic public investment”.

Bolivia is an interesting example because despite being a primary commodity exporter, its growth has come from public investment in infrastructure, which has improved productivity and stimulated private investment, which Rodrik also says has happened in Ethiopia and India.

So while these nations are ‘capitalist’, in the sense that some of the means of production are owned privately and labour works for the owners of this capital to produce surplus value, the central role of government spending and regulation means they are not ‘free market’ economies.

Noah Smith deliberately conflates ‘capitalist’ with ‘free market’, but knows full well the difference and what that difference means for his argument. Which is why he tries to blur the two concepts in the eyes of the reader.

Smith actually claims that the rapid increase in living standards in India has been the result of “substantial free-market reforms in the 1980s and 1990s”.

However, Rodrik quotes the Indian government’s chief economic adviser who says that:

I think two sectors holding back the economy are private investments and exports. That is why … public investment is going to fill in the gap.

Rodrik is clear – “The government has had to step in as both private investment and total factor productivity growth have faltered in recent years. These days, it is public infrastructure investment that helps maintain India’s growth momentum.”

The same goes for China which Smith claims is a free market miracle that has grown on the back of an export boom, which has been the result of the economy being unshackled from government regulation.

Think back to the early days of the GFC. At that point, Chinese exports fell significantly as the advanced economies went into meltdown.

As an aside – what caused the meltdown again – a bit too much deregulation combined with a healthy dose of capitalist dishonesty and incompetence!

I discussed China’s response to the crisis in this blog from May 2009 – Where the crisis means death!.

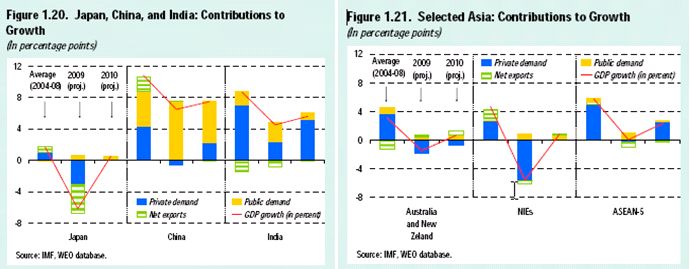

The IMFs Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific Report at that time produced the following graph, which split the contribution to real GDP growth into public demand (net government spending), private demand and net exports.

China stands out. Most people think of China’s growth coming from its burgeoning export sector. But it has a very strong domestic economy and a large public spending program – its called ‘nation building’.

Nations need to be continually built and the comparison between China’s performance with Japan (with virtually no public sector) and the performance of Australia and New Zealand, which have only miniscule growth originated from public spending, is compelling.

The IMF Report noted:

In China, GDP growth will also slow down notably from the average pace of the recent past. Still, the aggressive policy response is expected to support domestic demand and maintain growth at rates close to the level authorities consider necessary to generate jobs consistent with social stability. In particular, the massive program of public investment initiated late last year is expected to compensate for the decline in private investment and absorb productive resources no longer utilized in the tradable sector.

So the graph highlights, in my view, the importance of very large fiscal interventions. My Chinese friends tell me there is no discussion over there about the country drowning in debt and all of that nonsense. They know full well that they are sovereign in their own currency and can deficit spend to further their sense of public purpose.

So much for the ‘free market’ and economic liberalisation. When capitalism enters crisis it is bailed out by the currency capacity of government.

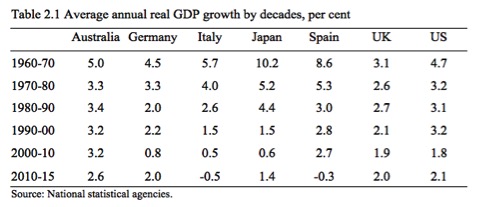

Further, consider the following Table, which shows the average annual real GDP growth rates by decade from 1960 for various countries.

The Table is, by the way, taken from chapter 2 of my Modern Monetary Theory textbook which I have been writing with Randy Wray. We have added a third co-author, Martin Watts, and the book is now nearing completion and will be published in the coming months. Hurray for that.

The sample of nations chosen include the three large industrialised European nations representative of the ‘north’ and ‘south’ (Germany, Italy and Spain) all of which a members of the Eurozone; Britain, a European nation outside the Eurozone; a small open economy predominantly exporting primary commodities and with a relatively underdeveloped industrial base (Australia), and two large, Non-European industrialised nations (Japan and the USA).

Several things are clear.

First, real economic growth has been lower on average in the current period than in the 1960s for each country.

Second, the European nations (Italy and Spain) have clearly performed poorly in the recent period.

Third, the European nations within the Eurozone, including Germany, have performed relatively poorly since 2000.

Fourth, Australia has generally performed better than the other nations in the table.

It is no surprise that the latter period has been associated with neo-liberal policy changes such as deregulation of labour in financial markets, reductions in government income support, stalled minimum wage levels, repressed real wages gross, cuts in government infrastructure spending and all of the rest of it.

We used to use the term ‘mixed economy’ to describe the full employment era in the Post Second World War period up until the 1970s. The private capitalist sector was complemented by a strong government sector, both in terms of regulation and direct spending support.

At this point, Noah Smith is forced to acknowledge that the “libertarian, free-market right has, in my opinion, greatly overreached in the last 35 years, especially in the U.S.”

He says:

In their zeal to kill the welfare state, libertarians and conservatives have ignored the crucial public goods that the government provides — infrastructure, research and development and other things that private companies won’t do enough of on their own.

The focus on slashing the welfare state also coincided with a dramatic rise in inequality in rich countries. Even as the world became more equal, the working class fell behind in the U.S., Europe and Japan, probably because of globalization. In other words, ardent libertarians reduced support for the poor and working class just as they began to need it more.

But, moreover, real GDP growth rates fell on average as did productivity growth. The failure of latter day capitalism is much more than the rising inequality.

Smith also acknowledges that “Most importantly, the right has ignored one incredibly critical fact: big government is a reality in all rich countries”.

So much for his ‘free market’.

When capitalism and the free market become more alike – the former fails. It is only when the government maintains a strong oversight on capital that the system operates to not only produce acceptable levels of employment but also more equitable distribution layer comes.

As Noah Smith concludes:

Excessive market liberalization, of the type pushed upon us by libertarians, runs the risk of depriving people of the government interventions they need and want. If government really is instrumental in creating growth, and much of the evidence supports this idea, then too much Reaganism might make us poorer …

In the end, the boring old mixed economy — a capitalist base with some socialism on top — remains the most successful economic system ever created.

Which is in conceptual terms light years away from the ‘free market economy’. It is the mixed economy that the respondents to the PEW survey were lending their support to not a system of economic organisation that takes a strong central government out of the picture.

Conclusion

It would have been less misleading to the readers for Smith to have inverted his article with the conclusion leading the argument.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Indeed, I’m happy to call myself a socialist because I see a mixed economy with a strong public sector supporting a dynamic competitive(monpoly/rent-free) private sector as the system which best delivers prosperity, high living standards and increased productivity.

To me it just seemed that Noah was saying that the hashtag was an extreme response by those using it in reaction to their confusion between ‘free market’ and capitalism. He points out that libertarians often miss important components of public spending in their thinking, and those using the hashtag (due to the confusion) are missing some of the benefits of capitalism – i.e. he is sitting on the fence advocating capitalism with a dusting of socialism, and the point of the article is to point out that the binary views of both parties are silly.

I know you have a issue with framing of arguments and loaded language, but to pick on one article out of the thousands posted that day with the same shortcomings seems a bit odd.

Regarding ‘Chinese drowning in debt-and all that nonsense”

Yes,public spending initiatives face no constraints,but that isn’t to say that overleverging and a build up of private debt in local banks isn’t an issue.The economy has been loaded up with debt which cannot be serviced.Probably because of insufficient demand,as the export sector has been lagging.as well as domestic underconsumption(so I am told at least ,most Chinese very look v. affluent as opposed to being austerians to me,plus their wages have risen,so I’m not really sure)

Jake, according to your description you are not a socialist; you seem to be a social democrat.

Bill,

I am eager to read your new economics book with Wray…who will publish? EE?

Thanks

William

The government is instrumental in creating growth in the economy, some truly productive capitalism is helpful, and working people are essential to having an economy in the first place. Elites?

Bill,

Smith is a twit. He’s the heir to the New Keynesians of the 1990s. But he is about half as clever. He flubs every argument he tries to engage with but seems to have gotten a column on Bloomberg somehow. Example:

https://fixingtheeconomists.wordpress.com/2014/09/29/noah-smith-fumbles-argument-endorses-post-keynesian-endogenous-money-theory/

Great article thanks Bill. Am learning.

“If you compare, for instance, the development of Mexico and the Soviet Union from 1913 until the year the Berlin Wall fell, “the Soviet Union’s growth over the period of communism put Mexico’s to shame,” according to Charles Kenney, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development. He points out that Soviet income per capita was 46% greater than Mexico’s in 1989, compared to just 1% larger in 1913.”

Fortune: Poor Germany: Why the east will never catch up to the west

Referring to:

“What Does the Eastern European Growth Experience Tell Us About the Policy and Convergence Debates?”

I just wonder, in the present system, do the economy serve people or do the people serve economy?

Because in the opinion polls, in europe at least, most people who work want more leisure time even if it would cut their income.

Present system is sick on so many levels. Others wanna work, but cant find work. Those who work want, on average, healthier work-life balance but can’t get one, because long working times serve will of the employers.