The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Europe’s future is bleak with an ageing population and policy failure

I read an interesting article that was published on December 18, 2015 by the Center for Global Development, which is one those centrist-type research and advocacy organisations that lean moderately to the right on economic matters. The article – Europe’s Refugee Crisis Hides a Bigger Problem – discusses what it considers to be “three population related crises”, two of which at the forefront of public attention (because they are moving fast) – the “refugee crisis” and the “terrorism crisis”. The third is “Europe’s slow moving and in inexorable ageing crisis”, which is largely being ignored in the public debate. The article provides a basis to link the three crises together – in the sense that “Europe actually needs millions of migrants a year to mitigate its ageing crisis”. While I have some sympathy with the article, there are many omissions that reflect the bias of the author. Two major issues – mass unemployment and productivity growth are ignored completely. The emphasis in the article is on whether the public sector can afford not to bring in more people to offset the ageing of the EU28 population. That emphasis discloses the bias of the author and diminishes the strength of the article.

The article argues that under “UN “zero migration” variant population projections by 2050, the labor force aged (15-64) population shrinks by 62 million in core Europe”, which is a substantial shift in 35 years in the composition of the population.

The other aspect of this shrinkage in the labour force is the projected rise of 45 million in the over 65 year age bracket.

The article says:

Never has the combination of fertility changes and improvements in longevity produced such dramatic inversions of the demographic pyramid so that the aged so dramatically exceed the young.

The Eurostat population projections, which are different from the UN projections that the cited article uses, but which tell a similar story, show that in 2015 for the 28 nations making up the European Union, there were 2 persons of labour force age (15-64) to every person outside of the labour force age bracket.

By 2050, under Eurostat’s No Migration assumption, this ratio falls to 1.2, and by 2080, remains at 1.2.

Similarly, the ratio of persons of labour force age to the number of persons above 65 years of age was 3.6 in 2015. Under Eurostat’s No Migration assumption, this ratio falls to 1.8, by 2015 and by 2080, it falls to 1.7.

Under Eurostat’s Main Scenario, the ratio of persons of labour force age to the number of persons outside of the labour force age bracket falls from 2 in 2015 to 1.3 by 2050 and remains at that level by 2080.

Similarly, the ratio of persons of labour force age to the number of persons above 65 years of age was 3.6 in 2015. Under Eurostat’s No Migration assumption, this ratio falls to 2 by 2050 and remains at that level by 2080.

These projections more or less accord with those outlined in the cited article.

The author then does some calculations which show that if the European Union wanted to maintain the current ratio of those in the labour force to those who were retiring (under the No Migration assumption above this ratio is 3.6 – the author uses 3.3 which is taken from the UN projections) then it would require for “each one million new retirement aged people requires 3.3 million new people of labor force age”.

He shows that under these assumptions Europe will be “212 million people short” given the shrinkage of 62 million people from the current labour force age bracket.

He concludes that:

The projected labor force aged population in 2050 is 227 million, but would have to be 439 million to sustain the projected 132 million Europeans over 65 at the current ratios.

The author also questions whether the current ratio of 3.3 (UN projections) is “sustainable” because:

Even at that ratio the combined social protection programs that Europe is justly famous for-generous pensions, universal health care-require very high tax rates on workers to sustain.

If the ratio drops to 1.7, as projected, “It is hard to imagine sustaining anything like Europe’s current social programs with that ratio of potential workers to retirees”.

He projects that Europe will “require 6 million additional labor force aged population a year” and that the current “refugee crisis” is only delivering “800,000 potential refugees” to “Europe via the Mediterranean in 2015 and 2016”, which is “less than a fifth of the total that would be needed not to solve, but just to mitigate the ageing crisis”.

The implication of the article is that Europeans are going to have to do abandon their denial that it can have low rates of migration while enjoying “quality health care” and retirement “at a reasonable age”, while preserving “their national and sub- national identities and cultures”.

The other implication of the article is that the public sector will not be able to afford the demands that the ageing population will place on government fiscal policy, and it high rates of migration of labour force age people is required.

There are some things in the article that I agree with but there are many things that are not mentioned or emphasised. The premise of the article is really based upon headcount rather than any qualitative indicators (such as the quality of the labour).

First, the article doesn’t mention the entrenched unemployment in Europe at all, which as you will see, makes the problem of ageing much more significant.

Second, the article doesn’t mention productivity, which is one of the keys to dealing with arising dependency ratio.

Third, the article doesn’t discuss the likelihood that the current fiscal constraints on Member States in the Eurozone, which makes up a significant part of the EU 28, are artificial and can be changed. In other words, the population trends, which are indisputable, will place a great deal of pressure on governments in the Member States, and this pressure is likely to further undermine the effectiveness of an already dysfunctional monetary system.

Eurostat’s Main Scenario, which it uses for population projects, is outlined in – The 2015 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies – and I won’t go into detail here. There are detailed assumptions about birth and death rates, net migration rates, labour force participation rates etc.

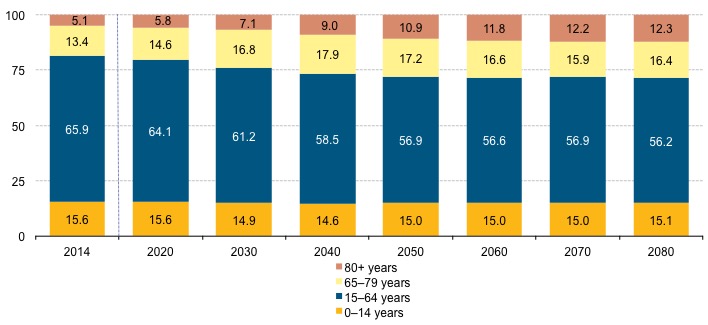

The following graph is produced by Eurostat to show the shifting age composition of the EU 28 from 2014 to 2080 under the Main Scenario.

It is quite clear that the labour force age group shrinks from 65.9 per cent of the total EU 28 population in 2014, to 56.2 per cent in 2080. The under-15 cohort maintains the same share, more or less.

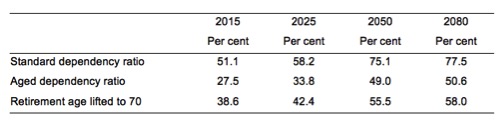

These movements lead to dependency ratio calculations that I outline in the following Table.

Does the dependency ratio matter?

It does but not in the way that is usually assumed.

What are these different measures in the Table?

The standard dependency ratio is normally defined:

As 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years).

Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old.

The aged dependency ratio is calculated as:

100*Number of persons over 65 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

Statisticians also compute a child dependency ratio:

100*Number of persons under 15 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

The total dependency ratio is the sum of the two. You can clearly manipulate the ‘retirement age’ and add workers older than 65 into the denominator and subtract them from the numerator. This will have the effect, as shown in the Table above, of reducing the dependency ratios.

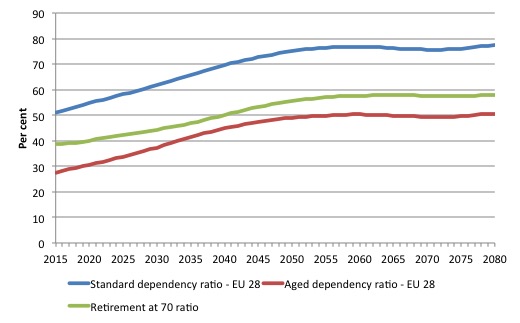

The following graph uses Eurostat Main Scenario to show the standard and aged dependency ratios based on a retirement age of 65 and the standard ratio if the retirement age rises to 70 (green).

One of the mainstream responses to the ageing issue is to push is on to increase the retirement age. It certainly reduces the dependency ratio somewhat and means that more people with great experience can mentor the youth coming into the labour force without experience.

That is, in a perfect world where the youth actually get jobs and the older workers retain their skills. As we know, current day Europe is far from being that type of world.

However, if we want to actually understand the changes in active workers relative to inactive persons (measured in terms of those who are not producing national income) over time then the raw computations described above are inadequate.

To get a more accurate indication of the stress that an ageing population places on the production possibilities of the economy we have to consider the so-called – Effective dependency ratio – which is the ratio of economically active workers to inactive persons, where activity is defined in relation to paid work.

These measures, while an improvement, suffer from the same problem that all measures that count people in terms of so-called gainful employment – they ignore major productive activity like housework and child-rearing. The latter omission understates the female contribution to economic growth.

Given those biases, the effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age (15-64 or whatever) are actually producing. There are many people in this age group who are also ‘dependent’. For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and early retirees fit this description.

I would also include the unemployed and the underemployed in this category although the statistician counts them as being economically active.

If we then consider the way the neo-liberal era has allowed mass unemployment to persist and rising underemployment to occur you get a different picture of the dependency ratios.

So here is some arithmetic that takes into account the impact of unemployment and underemployment in calculating the dependency ratios. It does not consider the other sources of inactivity within the working age population mentioned above and, in that sense, biases the dependency ratio measures downwards.

Eurostat’s Main Scenario for its population projections out to 2080 assumes that the participation rates for each group will be as follows:

1. 20-24 cohort – 61.6 per cent (2013) 62.6 per cent (2060)

2. 25-54 cohort – 85.3 per cent (2013) 85.9 per cent (2060)

3. 55-64 cohort – 54.4 per cent (2013) 70.2 per cent (2060)

I then used these assumption to simulate the labour force for each age cohort (assuming the shifts between 2013 and 2060 occur in a linear fashion).

I am assuming no-one above 65 works (and at present it is a very small percentage). This assumption biases my effective dependency ratio results upwards.

I used a 5 per cent unemployment rate for the EU 28 as a benchmark. You can think of this in any way you like. I certainly don’t believe it constitutes a true full employment situation and it is slightly lower than the unemployment rate that prevailed in 2007 in the EU 28.

At any rate, the simulations scale proportionately up or down depending on what unemployment rate one chooses as the benchmark compared to my benchmark here.

I also took account of the fact that – Eurostat – estimate that underemployment in 2015 for the EU 28 was 4.2 per cent. I am ignoring the other categories of marginal attachment to the labour force, which means my estimates will be biased downwards (providing a better indication that is justified).

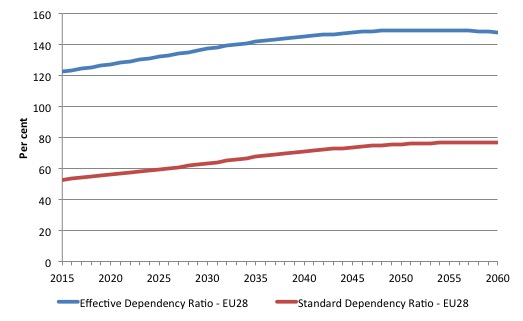

The following graph shows

Then taking the NAIRU assumption (5 per cent constant) and assuming underemployment remains constant at 5 per cent (it is currently nearly 8 per cent) you can compute the active dependency ratio with the NAIRU assumptions. I also computed the same using the full employment assumption of 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment.

The following graph shows the Effectuve or active dependency ratio compared to the standard dependency ratio defined above from 2015 to 2060.

In 2015, the standard dependency ratio for the is 53 per cent whereas if you consider the approximate effective ratio under the assumptions deployed, the dependency ratio is 121 per cent.

By 2060, the projected dependency ratios would be 77 per cent (standard) and 147 per cent (effective or active).

Taking into account unemployment and underemployment means that in 2015, this means that there are 0.8 workers for every non-worker who is inactive. By 2060, this deteriorates further to 0.68 workers for every non-worker.

That puts a different light on things.

The greatest initial gain that can be made to reduce dependency ratios would be to restore true full employment and at least reduce unemployment to below 5 per cent.

The real issues with dependency ratios

The reason that mainstream economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions of the government financial constraint.

So a rising dependency ratio suggests that there will be a reduced tax base and hence an increasing fiscal crisis given that public spending is alleged to rise as the ratio rises as well.

So if the ratio of economically inactive rises compared to economically active, then the economically active will have to pay much higher taxes to support the increased spending. An increasing dependency ratio thus is alleged to strain the fiscal deficit out and lead to escalating debt.

In general, these concerns are flawed if they are applied to a currency-issuing national government such as the US, Australia, the UK, and Japan.

The concerns have more credence in Europe, particularly the Eurozone, where the Member States have ceded their currency sovereignty.

In the Eurozone, the Member States are highly constrained in a fiscal sense and are probably not equipped to deal with the shifts in the dependency ratio as projected above.

The article cited in the introduction provides no answers to how that constraint might work out or be alleviated, other than to argue that migration rates into Europe should increase.

The reality is that the European Commission is going to come under increasing pressure to deal with the unworkable fiscal constraints as the population mass ages.

Second, the major crisis that is looming in Europe, as elsewhere, with respect to the ageing of the population is is a real one.

Wolfgang Münchau’s article in the Financial Times (January 18, 2016) – Gloom gathers over the challenges that Germany faces – makes the interesting point that:

It is tempting to think of refugees and migrants as a new source of labour. But in this case this just is not true, at least not for now. The majority of those who arrive in Germany lack the skills needed in the local labour market. They will enter the low wage sector of the economy, and drive down wages, producing another deflationary shock. This is the last thing Germany and the eurozone need right now.

The article cited in the introduction assumes that merely augmenting the working age population will be sufficient. It is highly likely that governments will have to do provide extensive formal education and training programs to ensure any new entrants to the European labour market have high skills.

In general, as long as there are real productive resources available, which can be brought into productive use, the ageing problem can be minimised.

The secret to dealing with the ageing population is to ensure that the active working age population is maximised (which means that full employment is achieved and sustained) and that labour productivity levels increase significantly.

The former requires a massive job creation strategy from the European polity, which has been absent in the last decade or more.

Productivity growth comes from research and development and significant, on-going investment in education and training.

In this context, the type of austerity policy strategy that is being driven by the European Commissions will undermine the future productivity and provision of real goods and services in the future.

The irony is that the pursuit of fiscal austerity leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

Most importantly, maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. The emphasis in mainstream intergenerational debate that we have to lift labour force participation by older workers is sound but contrary to current government policies which reduces job opportunities for older male workers by refusing to deal with the rising unemployment.

Anything that has a positive impact on the dependency ratio is desirable and the best thing for that is ensuring that there is a job available for all those who desire to work.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future. The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

But all these issues are really about political choices rather than government finances. The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

The ECB has all the financial resources it requires to ensure that Member State governments can achieve full employment and invest heavily in education and training. Unfortunately, the structure of the European monetary system precludes such responsible policy positions.

The European mantra about fiscal policy ‘discipline’ will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term. The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such ‘discipline’ reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results.

Conclusion

Long-run productivity growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future.

Principal determinants of long-term growth include the quality and quantity of capital (which increases productivity and allows for higher incomes to be paid) that workers operate with.

Strong investment underpins capital formation and depends on the amount of real GDP that is privately saved and ploughed back into infrastructure and capital equipment.

Public investment is very significant in establishing complementary infrastructure upon which private investment can deliver returns.

A policy environment that stimulates high levels of real capital formation in both the public and private sectors will engender strong economic growth.

If we adequately fund our public education institutions and further improve labour productivity then the real burden on the economy will not be anything like the scenarios being entertained.

But then when the European Commission allows nations like Greece and Spain to sustain unemployment rates above 25 per cent or so and youth unemployment rates above 50 per cent, there is little hope for long-term prosperity in the face of an ageing population.

The harvest in Europe of the ageing population will be worse than they can currently imagine under current policy settings.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2016 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Excellent comment!

I could not agree more to your analysis. It is difficult to believe that these misconceptions referring to demographic aging and its supposed implications for the economy seem to enjoy an eternal life. The concept of demographic aging was used some 15 years ago to promote “capital-based” retirement schemes (to gradually replace or supplement the pay-as-you-go system). The banks and insurance companies became silent after the GFC, but seemingly another attempt is being launched to promote their financial products.

Frankly, any attempt to reason about demographic trends using European averages is meaningless. Real dependency ratios vary widely, whether due to un/underemployment, or the proportion of the population economically active (workers per household, household composition). What is the difference between a dependency ratio of 60 and 120? No need to speculate; the data already exists – just do a cross-country comparison. (See the 4th comment of this blog post 😉

The second point is that, as Bill says, labour productivity is just as important as the active/inactive ratio. As long as an economy has a sufficient number of people employed in the high productivity/tradeable goods sector, the remainder can be employed in more low intensity/human oriented sectors, and the latter will of course be necessary when the elderly population has increased by c. 50% (social services/healthcare).

This type of research subject to Bill’s analysis here is completely unrealistic. It assumes business as usual will continue, that our planet is not limited in resources and that growth will just keep happening. Well, it won’t.

Our civilization peaked in the late 1960’s perhaps early 1970’s when we were able to maximise our energy use. Energy is our controlling parameter. The maximum return on investment occurred in 1930 at 100:1. By 1970 it was down to under 40:1. Now it’s down to under 15:1. For tar sands it’s 3:1. So we use ever more resources to get the oil we need just to mark time. Next we will begin to see the Export Land Effect. The end game of that will be the inability to buy oil once the exporting countries find they need it themselves. Bad news for oil importing countries.

Too cheap oil will mean it stays in the ground. Too dear means it will not be bought and consumption will tank. Sheik Yamani is on record as stating that by 2030 all oil will be left in the ground. We cannot rely on renewables as our oil and coal, gas etc is too vast to match with renewables. For instance we would need 200 dams[!] each the size of China’s Three Gorges Dam just to match one year’s oil consumption with electricity. And we still need oil. We eat oil. What I write here is the tip of an iceberg of confronting data.

We are in a crisis of overconsumption. Unsustainable, we need a planet and a half now. That has to reverse but no one wants to admit we have this problem. So worthys make analyses based on wishful thinking. The report is not just unrealistic, it is ridiculous. But it’s symptomatic of our delusions. Our delusions will be our undoing.

The narrative in these sort of reports is to push a particular political line.

Here in the UK there are 1.1 million people over 65 in employment and 1.7 million unemployed. The number over 65 will continue to rise – firstly as a result of banning compulsory retirement and secondly as a result of the constant rise in the state pension age. The UK is looking at 69 to 70 for anybody retiring in the 2050s. So why are the stats still using 65?

How all this ties into the constant push amongst the regressive left for ‘basic income’ is beyond me. ISTM that the most sensible way to get basic income in place is to push for the retirement age to be lowered to 60 and below (which in the UK would shift the employment rate amongst the age cohort from 70% to about 11%). Since that never happens it tells you that basic income is really about getting Latte Money to the chattering classes, rather than spreading out the ‘shrinking amount of work’ and giving the poor a leg up.

I have often wondered when people talk of the ageing population and how great a problem it is with so few young people to support them of how that scenario worked after the first and second world wars when so many young people died. The start of the golden era was started prior to the second world – certainly here in New Zealand. After the Second World War there would have been so few young people in relation to the old people and so much infrastructure to repair as well. How was it done AND it was done?

Dear Bill

The idea that a person becomes unsuitable for work at the age of 65 should be abandoned. We can’t live in a world where people live longer and longer and stay healthy longer and longer but insist on retirement at the age of 65 or sooner. The retirement age has to be gradually pushed up to 70. A senior should be defined as a person over 70, not someone over 65. True, many people between 65 and 69 are unfit to work. However, there are people unfit to work at every age. For them, there should be a disability pension.

The best old-age security in my opinion is a universal pension financed from general revenues. That way everybody is covered. If we make this pension fully taxable, then the rich will in effect receive less than others because they have to pay a hefty percentage back. A lot of people seem to think that funded pensions are a protection against aging. That is complete nonsense. People who don’t work are always supported by those who do work, whatever the financial assets of the non-workers are.

Suppose that I have 10 rental houses. Do those houses support me? No! It is my tenants who support me. If those tenants lose their jobs, I will lose my income too. Suppose that everybody under 65 in Canada were to die tomorrow, would Canadian seniors then enjoy high prosperity because they now own everything in the country that isn’t owned by foreigners? Of course not, they would starve and freeze in the dark. Yet, time and time again we hear that the solution to the aging problem is to encourage people to save more.

Not all European countries are in the same boat. The fertility rate is 2 in France, 1.8 in Sweden and 1.4 in Germany. Assuming that 2.1 is the replacement fertility rate, then 100 Frenchmen will have 91 grandchildren, 100 Swedes will have 74 grandchildren, and 100 Germans will have 45 grandchildren. Those are big differences.

Regards. James

The present global population is >7 billion. That is about double the notional sustainable level which is probably Panglossian anyway.

The natural methods of population control are war,disease and famine which are Malthusian and have a long history.

There is another way but it requires some degree of intelligence and insight. It is called reducing the birth rate to below replacement level so that there is a gradual,orderly decline in population to a true sustainable level.

Aging demographics will inevitably accompany this process. This is not a terminal state. It seems to me that adjusting our system to it would be a lot easier than continually trying,unsuccessfully,to cope with increasing numbers.

It seems to me that the majority of the the current population of economists,social scientists,politicians etc who can be lumped together conveniently into the Booster Basket (Cases) are lacking intelligence and insight.

War is not “a natural process”.

The analysis is based on the hypothesis that world political and economical stability will continue as during the last two generations. Stability was based on the strong hegemony of the United States. But nothing last forever, and the chaotic spots may expand and cover the world.