These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Central bank propaganda from Minneapolis

My blog in the next week or so will be possibly rather holiday-like given the time of the year and the fact that I have rather a lot of travel and related commitments to fulfil over that period. So I will be pacing myself to fit it all in. Today, a brief comment on an article that appeared in the December 2015 issue of The Region, a publication of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis – Should We Worry About Excess Reserves (December 17, 2015). It is that one of those articles that suggests the author hasn’t really been able to see beyond his intermediate macroeconomics textbook and understand what is really been going on over the last several years.

The essence of the article is that:

Banks in the United States have the potential to increase liquidity suddenly and significantly-from $12 trillion to $36 trillion in currency and easily accessed deposits-and could thereby cause sudden inflation.

Why is that? Well, according to the author, US banks have large volumes of excess reserves, and:

… the nation’s fractional banking system allows banks to convert excess reserves held at the Federal Reserve into bank loans at about 10-to-1 ratio. Banks might engage in such conversion if they believe other banks are about to do so, in a manner similar to a bank run that generates a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Note the use of the word ‘might’, an uncertainty that is characteristic of these ridiculous, speculative type articles. To style of prose is along the lines of ‘well the sky might fall in’ all ‘all hell could break loose’ if pigs learned to fly – that sort of reasoning.

The author wants to generate, in the more irrational readers, a sort of hysteria that something dreadful might happen unless the ’cause’ is immediately addressed.

Of course, they clothe their predictions in such uncertainty that they can never be wrong.

But, while their predictions are qualified by ‘might’ and ‘could’ type words, their depiction of how the monetary system and the banking sub-system within it operate can be incorrect and in this case it clearly is.

The article is really just a rehearsal of the intermediate textbook notion of the money multiplier.

For background, please read the following blogs:

1. Money multiplier – missing feared dead

2. Money multiplier and other myths

Consider the statement that the “nation’s fractional banking system allows bank to convert excess reserves held at the Federal reserve into bank loans”.

An innocent reader would be forgiven for concluding that banks loan out their reserves to customers who seek credit.

So if the commercial banks in the US banking system “currently hold $2.4 trillion in excess reserves: deposits by banks at the Federal Reserve over and above what they are legally required to hold to back their checkable deposits” then such a reader would conclude that the banks, in general, have massive extra capacity to make loans.

Such a reader would then also be forgiven for concluding that if banks suddenly released those excess reserves into the economy then there would be so much money sloshing around that inflation would accelerate quickly and chaos would ensue.

The problem is that the innocent reader might be forgiven but their ‘understanding’ would be wrong at the most elemental level.

The author of this article draws on several aspects of mainstream economic theory that is categorically been shown to be errant.

First, the old classical Quantity Theory of Monetary (QTM) is wheeled out so that characters like David Ricardo and Milton Friedman are noted and their contention that “the amount of liquidity held by economic actors determines prices” is stated, without qualification.

The author says “Greater liquidity is associated with higher prices”, although he does note that “the correlation between changes in M2 and prices is not tight in the short run”. There is a curious dissonance here between correlation and the assertion of causality.

Mainstream economists link the expansion of the money supply with accelerating inflation. It is the most intuitive part of the neo-liberal story and the one that resonates with the public.

While the QTM was formulated in the 16th century, the idea still forms the core of what became known as Monetarism in the 1970s.

First, a small bit of theory. The QTM postulates the following relationship: M times V equals P times Y, which can be easily described in words as follows. M is a symbol for how much money there is in circulation, that is, the money supply. V is called the velocity of circulation in the textbooks but simply means how many times per period (say a year) the money supply ‘turns over’ in transactions.

To understand velocity, think about the following example. Assume the total stock of money is $100, which is held between the two people that make up this hypothetical economy. In the current period, Person A buys goods and services from Person B for the $100 it currently holds. In turn, Person B uses the $100 to buy goods and services from Person A.

The total transactions equal $200 yet there is only $100 in the economy. Each dollar has thus been used ‘twice’ over the course of the year. So the velocity in this economy is two.

When we make transactions we hand over money, which then keeps being circulated in subsequent purchases. The result of M times V is equal to the total monetary transactions in the economy per period, which is a flow of dollars (or whatever currency is in use).

The P times Y is the average price in the economy (P) times real output produced (Y), which sums to what we call nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The national statistician estimates the total sum of all the goods and services produced to get real GDP and then values this in some way using the price level to get a monetary measure of total production.

So P times Y is the total money value of the output produced in the period.

At this level, the relationship M times V equals P times Y is nothing more than an accounting statement that says that the total value of spending (M times V) in a period must equal the total monetary value of output (P times Y), that is, a truism.

It is true by definition and thus totally unobjectionable. How does the QTM become a theory of inflation? The answer is that the inflation theory uses a sleight of hand.

The Classical economists, who pioneered the use of the QTM, assumed that the labour market would always be at full employment, which means that real GDP (the Y in the formula) would always be at full capacity and thus could not rise any further in the immediate future.

They also assumed that the velocity of circulation (V) was constant (unchanged) given that it was determined by customs and payment habits. For example, people are paid on a weekly or fortnightly basis and shop, say, once a week for their needs. These habits were considered to underpin a relative constancy of velocity.

These assumptions then led to the conclusion that if the money supply changed, the only other thing that could change to satisfy the relationship M times V equals P times Y was the price level (P).

The only way the economy could adjust to more spending when it was already at full capacity was to ration that spending off with higher prices. Financial commentators simplify this and say that inflation arises when there is ‘too much money chasing too few goods’.

This is the simplistic contention that appears in this Federal Reserve of Minneapolis article.

The problem with the theory is that neither of the required assumptions holds in the real world.

First, there are many studies which have shown that velocity of circulation varies over time quite dramatically. Second, and more importantly, capitalist economies are rarely operating at full employment.

The Classical theory essentially denied the possibility of unemployment. The fact that economies typically operate with spare productive capacity and often with persistently high rates of unemployment, means that it is hard to maintain the view that there is no scope for firms to expand the supply of real goods and services when there is an increase in total spending growth.

If a firm has poor sales and lots of spare productive capacity, why would it hike prices when sales improved?

Thus, if there was an increase in availability of credit and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will respond by increasing the supply of goods and services to maintain or increase market share rather than push up prices.

In other words, an evaluation of the inflationary consequences of increased spending in the economy should be made with reference to the state of the economy.

If there is idle capacity then it is most unlikely that an increased nominal spending growth will be inflationary. At some point, when unemployment is low and firms are operating at close to or at full capacity, then any further spending will likely introduce an inflationary risk into the policy deliberations.

But that sort of conditionality is nothing at all like what this article is claiming.

Further, there is the sleight of hand between use of the term ‘liquidity’ and ‘spending’ in the article. The two are not equivalent. Spending can create an inflation risk (as above) but liquidity held as bank deposits cannot.

However, there is something even more basic wrong with this article.

The author says:

What potentially matters about high excess reserves is that they provide a means by which decisions made by banks-not those made by the monetary authority, the Federal Reserve System-could increase inflation-inducing liquidity dramatically and quickly.

The author buttresses this outrageous claim with the additional assertion that “the belief by some banks that other banks are (or will soon be) converting their excess reserves to loans could cause them to convert their own: The belief can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

He likens this to a “bank run (or panic) or an attack on a fixed exchange rate regime”.

Underlying this narrative is the author’s belief in the money multiplier mechanism, a basic element of mainstream monetary theory – and one of the most incorrect parts of that body of work.

Students are introduced to the money multiplier early in their studies. It is an article of faith in mainstream thinking.

It is asserted, erroneously, that by manipulating the monetary base, the central bank can control the money supply.

Milton Friedman, the father of Monetarism, once said in relation to the US monetary system that:

… the Federal Reserve System essentially determines the total quantity of money; that is to say, the number of dollars of currency and deposits available for the public to hold. Within very wide limits, it can make this total anything it wants it to be.

[Reference: Friedman, M. (1959) ‘Statement and Testimony’, Joint Economic Committee, 86th US Congress, 1st Session, May 25. http://0055d26.netsolhost.com/friedman/pdfs/congress/Gov.05.25.1959.pdf].

Later in 1968, as the Monetarists were gaining traction in the public debate, Friedman, in his famous – Presidential Address – to the American Economic Association, said that the central bank should publicly adopt:

… the policy of achieving a steady rate of growth in a specified monetary total …

Unfortunately, like most aspects of the Monetarist doctrine, the theory doesn’t match the reality.

The ‘monetary base’ is measured as the notes and coins in circulation or in bank vaults plus bank reserves held at the central bank. It is understood that central banks can add ‘money’ to the bank reserve accounts whenever they choose.

After all, they can create money ‘out of thin air’.

The money supply is defined in a range of ways – from very narrow (a small number of components) to broad (more components). The narrowest measure, M1, includes only notes and coins in circulation and bank and cheque account deposits on demand (that is, funds that can be withdrawn instantly).

Broader measures such as M3 include items such as longer-term deposits, which require more than 24-hours’ notice before withdrawal is permitted. The definitions also vary across nations.

The money multiplier is then defined as the money supply divided by the monetary base. The textbook argument goes that the central bank controls the ‘base money’ in existence and then the act of credit creation in the private banking system multiplies this base up to create the money supply.

The determinants of the money multiplier need not concern us here but relate to various parameters in the banking system (for example, the quantity of notes and coins that depositors wish to hold and any required reserves that the banks must hold).

A simple story to get the concept across is that someone deposits a sum in a bank to earn some interest. The bank then keeps some of that deposit in reserve to meet the daily withdrawal behaviour and lends the rest out at a higher interest rate in order to profit.

The recipient of the loan spends the money, which ends up as a deposit in some bank or another. That bank, in turn, lends most of this new deposit out, and the process continues. The resulting money supply expands as these deposits multiply.

The conception of the money multiplier is really as simple as that.

The Federal Reserve of Minneapolis article channels this type of reasoning – “Since each dollar of bank deposit requires approximately only 10 cents of required reserves at the Fed, then each dollar of excess reserves can be converted by banks into 10 dollars of deposits. That is, for every dollar in excess reserves, a bank can lend 10 dollars to businesses or households and still meet its required reserve ratio.”

He then produces some arithmetic, presumably to demonstrate he can add up and multiply, which shows the consequences of this 1-to-10 multiplier effect.

The only problem is that he appears oblivious to the flaws in the theory.

There are two major flaws.

First, the empirical evidence clearly shows that empirical estimates of the money multiplier are not constant and so can hardly be used to make predictions.

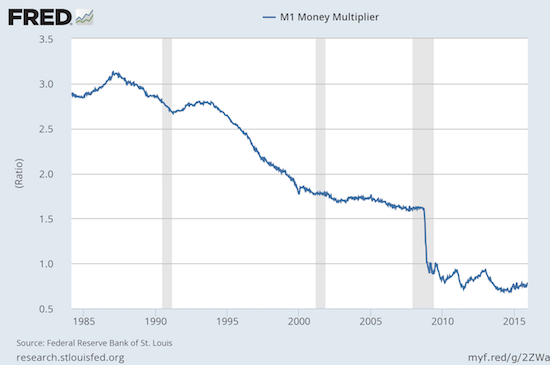

The following graph shows the estimates of the ‘money multiplier’ for the US using the so-called M1 measure of the money supply. The pattern would be the same if we had used a broader measure of the money supply.

If one is to postulate a causal relationship between the monetary base and the money supply mediated by this so-called money multiplier then the multiplier would have to be stable or predictable.

The multiplier has not exhibited stability in either the US or anywhere else for that matter and thus serves no useful basis for predicting the money supply.

Mainstream commentators attempted to argue that with QE driving up excess reserves in the banking system, the multiplier fell, which was an attempt to explain the sudden drops you can see in the graph.

However, this defence is an example of the ad hoc reasoning that permeates economic theory. Whenever the mainstream paradigm is confronted with empirical evidence that appears to refute its basic predictions, it creates an exception by way of response to the anomaly and continues on as if nothing had happened.

Students are not told that the measured multiplier is a moving feast and moves around like a Mexican jumping bean. Moreover, the measured multiplier was clearly unstable in the pre-crisis period, which means the special crisis case explanation for the instability fails.

Second, the stylised textbook model of the banking system isn’t remotely descriptive of the real world.

In the real world, banks do not wait for depositors to provide reserves before they make loans. Rather, they aggressively seek to make loans to credit worthy customers in order to profit.

These loans are made independent of a bank’s specific reserve position at the time the loan is approved. A separate department in each bank manages the bank’s reserve position and will seek funds to ensure it has the required reserves in the relevant accounting period.

hey can borrow from each other in the interbank market but if the system overall is short of reserves these transactions will not add the required reserves.

In these cases, the bank will sell bonds back to the central bank or borrow from it outright at some penalty rate. At the individual bank level, certainly the ‘price’ it has to pay to get the necessary reserves will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds.

But the reserve position per se will not matter.

For its part, the central bank will always supply the necessary reserves to ensure the financial system remains functional and cheques clear each day.

The upshot is that banks do not lend out reserves and a particular bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet by lending is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements that might be imposed by the central bank.

Loans create deposits, which are then backed by reserves after the fact.

It appears that this Federal Reserve of Minneapolis author hasn’t understood any of this nor read recent research papers from other central banks, for example, the Bank of England.

In recent years, in the face of all this hyperinflation angst, several central banks published articles which showed how far fetched the monetary theory is that is taught to students and espoused by mainstream economists and financial commentators.

They showed that real world banking doesn’t operate in the way the textbooks claim.

Among the enlightening reports was the Bank of England article in the First-quarter edition of the 2014 Quarterly Bulletin – Money creation in the modern economy.

The two central conclusions were:

The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks:

- Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.

- In normal times, the central bank does not fix the amount of money in circulation, nor is central bank money ‘multiplied up’ into more loans and deposits.

These conclusions are devastating for mainstream economics and for the analysis presented in the Federal Reserve of Minneapolis article, specifically.

The Bank of England further notes that “in reality … commercial banks are the creators of deposit money … the reverse of the sequence typically described in textbooks” and that the “money multiplier theory … is not an accurate description of how money is created in reality”.

These insights lead to the conclusion that “neither are reserves a binding constraint on lending, nor does the central bank fix the amount of reserves that are available”.

In terms of the determinants of the broad money supply, the Bank of England ratifies the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argument that “lending creates deposits”, which then creates money.

The Bank of England also highlighted the:

… related misconception … that banks can lend out their reserves … Reserves can only be lent between banks … consumers do not have access … [to central bank reserve accounts].

This insight is also confirmed in an interesting article published in September 2008 by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in their Economic Policy Review entitled – Divorcing money from monetary policy.

We learn that commercial banks require bank reserves for two main reasons. First, from time to time, central banks will impose reserve requirements, which means that the bank has to hold a certain non-zero volume of reserves at the central bank. Most nations only require the banks to keep their reserves in the black on a daily basis.

Second, the FRNBY states that “reserve balances are used to make interbank payments; thus, they serve as the final form of settlement for a vast array of transactions”.

There is daily uncertainty among banks surrounding the payments flows in and out as cheques are presented and other transactions between banks are accounted for.

The banks can get funds from the other banks in the interbank market to cover any shortfalls, but also will choose to hold some extra reserves just in case. If all else fails the central bank maintains a role as lender of last resort, which means they will lend reserves on demand from the commercial banks to facilitate the payments system.

When the central bank adds funds to these reserve accounts (for example, when conducting quantitative easing), the Bank of England tells us that:

… the new reserves are not mechanically multiplied up into new loans and new deposits as predicted by the money multiplier theory.

The Bank of England also concludes that the existence of new reserves, even if they are well in excess of the banks’ requirements to operate an orderly clearing system, “do not, by themselves … change the incentives for the banks to create new broad money by lending”.

The question then is, why are students in our universities forced to learn material that has no foundation in the system they are purporting to understand? The answer is that the educational opportunity is replaced by a propaganda exercise to suit ideological agendas.

The other question is, why does a branch of the Federal Reserve Bank in America allow an author to publish such misrepresentations of the way the banking system operates?

I won’t consider the formal gymnastics that the author implies to justify why none of the claims made in the article have eventuated.

In the conclusion, the author really demonstrates the problem that arises when a flawed model of the monetary system is used.

He says that a:

… potential solution is for Congress to make the policy and legal changes necessary to convert excess reserves into required reserves by dramatically increasing required reserve ratios, perhaps to 100 percent …

Which would make zero difference to the capacity of the banks to make loans.

Please read my blog – 100-percent reserve banking and state banks – for more discussion on this point.

Also, please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Conclusion

One might hope that the years of expanded central bank balance sheets and the deflationary tendencies around the world at present might have given some of these mainstream economists a reason to pause and really seek to understand what was going on.

In some cases (for example, the researchers at the Bank of England) that has happened. But there is still a hard-core of my profession that has waited for the clouds of crisis to lift and have simply returned to business as usual.

That is, peddling nonsense.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

It should be noted that the author of this ‘study’ (the one Bill goes over, debunks and critiques ably) is a tenured Professor of Economics, nay the Chairman of the Department of Economics at the University of Minnesota.

cf

1. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/files/research/cv/cphelan.pdf

2. http://www.econ.umn.edu/#

3. https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/christopher-phelan/

Perhaps not surprisingly Prof. C. Phelan received his Ph.D. Economics from the University of Chicago, August 1990.

Bill you have written money multiplier missing feared dead twice although they are different links 🙂

Bill,

You say “Loans create deposits, which are then backed by reserves after the fact”, and then suggest that that somehow shows that lack of reserves are never a constraint on commercial banks’ decision to lend.

Strikes me it all depends on what commercial banks which are short of reserves have to pay for emergency loans of reserves. If the central bank charges a penalty rate to commercial banks which are short of reserves, like 30%, then commercial banks would strictly limit the amount they lend.

Banks do not create money, they create credit. Think of banks as huge credit cards. You can take the credit and purchase items, but then have to pay back the credit with real (money created by a sovereign government) plus the interest.

Someone worked out that a $100,000 mortgage amortized over 20 years = $250,000. So, you pay back the $100,000 principle plus another $150,000 interest for an asset worth $100,000.

Banks do not create money nor do they distribute into the economy, they are sucking money out of the economy.

“Strikes me it all depends on what commercial banks which are short of reserves have to pay for emergency loans of reserves. If the central bank charges a penalty rate to commercial banks which are short of reserves, like 30%, then commercial banks would strictly limit the amount they lend.”

MMT never claimed that banks were not price contstrained. However the article Bill is writing about says that banks are quantity constrained, because quantity of ER went up, there might come inflation.

Things must truly be in crisis, when the central bankers have entered into a debate over what should be included in mainstream thinking on monetary theory.

That does make sense though because the one true theory is the one which accurately represents the interactions and obligations between government, central banks, and commercial banks, as a starting point, and central banks are the nexus were it all comes together. That is the only reality that matters for all practical purposes.

i wonder if you would be willing to talk about the Swiss Banks referendum “Switzerland to vote on banning banks from creating money” from https://www.rt.com/op-edge/327191-switzerland-money-banks-ban-referendum/

What does this really mean?

The velocity of money is really just an indication of the amount of liquidity of money as it circulates through the costing/pricing system that all enterprises of necessity are embedded in. The classic story used to illustrate the velocity of money is actually a disingenuous and incorrect one as it ignores the costing/pricing system above. Supposedly a man arrives in a town and pays the hotelier $30 for a room whereupon the hotelier takes that $30 and purchases $30 worth of groceries and the grocer then uses it to purchase $30 worth of hardware from a sundries store who then purchases $30 worth of fuel from a gas station and finally the gas station owner pays the hotelier $30 for a stay he booked a week ago. Supposedly the $30 produced $120 of purchasing power. Of course each merchant was actually using BUSINESS REVENUE as if it were individual income thus the costing/pricing system is ignored and an inaccurate picture of individual incomes and purchasing power is produced.

Neither the velocity of monies circulation nor GDP is an indicator of individual incomes and as the money totals by which it is measured still have not reached the place and time where all costs are terminally summed, namely retail sale to an individual, it is not a very useful or deeply analytic monetary metric. Analyzing the cost accounting data of any and macro-economically all enterprises to determine the ratio between total individual incomes and total costs of production is the 3 and 4 dimensional picture of the on the ground state of the economy and is “the gold standard” metric economists are looking for and missing.

Buyer Beware,

Money is defined in economics dictionaries as something like “Anything widely accepted in payment for goods and services.” What private banks supply you with when you get a loan is widely accepted in payment for goods and services. Ergo it’s money, isn’t it? The fact that the money has to be paid back at some point is irrelevant.

If the accepted form of money in some country is lumps of gold, and I borrow some lumps of gold from someone, that doesn’t stop those lumps being money.

Re the Swiss referendum, they’re voting on whether to implement so called “full reserve” banking or “100% reserve” banking as it’s sometimes called. That’s a system under which only the state issues or creates money, unlike the existing system under which the vast majority of money is issued/created by private banks.

Kristjan,

If banks face a penalty rate of interest for being short of reserves, then they just ain’t going to go short of reserves. Thus if the penalty rate is high enough then you’re right in theory to say banks face a “price constraint” not a quantity constraint, but in effect that’s a quantity constraint, seems to me.

Ralph seriously ? Banks lend money to credit worthy borrowers.

The cost of making the loans is factored into the price they charge the borrower.

It’s not much differentt to how you create strawmen here and then worry about where the straw will come from after you hit the post comment button.

Buyer Beware,

Banks do not create money, they create credit. Think of banks as huge credit cards. You can take the credit and purchase items, but then have to pay back the credit with real (money created by a sovereign government) plus the interest.

Arguably, it is customers that create loans. Customers sign loan docs — contractual agreements — new bank assets — which are the source of loan deposits — also contractual agreements, a bank balance.

In any case, loans are not paid back by Govt money, though interest *ostensibly* is. The fact is, in a thriving growing economy, with continual low-level credit expansion, for business and households, not to say “real estate bubble” or other credit bubble (tulip bulbs?), not to the point that people have to use credit for necessities like food or medical care, then new credit is used to pay off old credit.

If the govt was doing more spending AND customers were still expanding credit at the some same nominal rate, then the combination of HPM and bank credit could be “too much money”. At some point, higher taxes would be necessary, NOT to “balance the budget” but to remove surplus cash from a saturated economy. The Govt would have to destroy some of its financial liabilities (our dollars) to prevent inflation.

On the other hand, expanding Govt spending, such as during past wars, is typically associated with selling of war bonds, aka savings, aka not-spending, so as to not have the govt compete with the private sector for limited resources such as steel, rubber, oil, labor, etc. That was true in the past, today it is unlikely as there’s no major enemy threats. China is much smaller, and an economic ally. Then again, who knows when it comes to geostrategy — Germany was a US partner too at certain times with Kaiser a/o Nazis.

Point being that short of outlawing the creation of bank IOUs, that form of accounting, denying credit to willing customers, banks and govt will BOTH expand the money supply, but if Govt was doing a JG and Medicare for All and other infrastructure deficit spending, far fewer people would be scrambling for payday loans out of desperation, or going bankrupt to pay the hospital — then consumer credit would be allocated to choice or bling, with proper regulations like Glass-Steagall to inhibit commercial banks engaging in financial speculation.

Thank you Steve, Ralph Musgrave, Alan Dunn, & Gary Goodman for your kind input. In order to truly understand my point, please understand that there is a huge difference between money created by a sovereign government and money created by banks and how it impacts the economy.

Currently, the sovereign governments are not issuing money in a manner that gets the money into the pocket of consumers. People do not have enough money to pay their bills and interest and taxes and then spend into the economy. People are expected to borrow from banks to pay their bills and spend. This practice is not sustainable. No one can borrow money to pay their interest payments. ‘Funds’ obtained through bank loans are different than sovereign issued money.

As Michael Hudson says, banks use bank loans to reallocate public assets into private profits.

Re: Ralph Musgrave – the Swiss referendum, they’re voting on whether to implement so called “full reserve” banking or “100% reserve” banking as it’s sometimes called. That’s a system under which only the state issues or creates money, unlike the existing system under which the vast majority of money is issued/created by private banks.

Yes, thank you. However, what does that mean? That consumers and businesses will no longer be able to borrow from commercial banks? I am wondering that since the commercial banks are limited to the loans they will be able to lend this will drive up interest rates (scarce commodity). The price of houses, cars, etc. might drop. My question was, what does this mean to the economy?

“However, what does that mean?”

Nothing of note. The current system is an ‘insured system’ – where the state funds only come out during a collapse to restore order. The proposed system is an ‘in specie’ system where the state funds are issued up front, but locked away via some equivalence mechanism.

There are other sleight of hands tricks to do with redefining what is called ‘money’ and what isn’t – none of which alters the nature of the system one iota.

Full reserve systems have no extra control points, no magic, no nothing. It is entirely an illusion.

The two systems are operationally identical, but you can use a change over to full reserve to hide the nasties in the mire – removing free banking, eliminating free interest bearing savings and putting up the cost of loans for example, all of which you could do in the current system but that would expose the regressive nature of such actions to the full glare of publicity.

Anybody who actually knows how banking works doesn’t really care which system is in operation. They’ll be able to carry on entirely as before – lending to who they like, for whatever purpose they like, at what margin they like, whenever they like.

Neil,

This is why the particularities of regulation and the philosophy behind it are so important. Sovereignty, national sovereignty, is utterly important for control of the system and yet the philosophy behind the governmental control must also be looked at and graciously “governed” and “controlled”,….and then policies aligned with that philosophy. Sovereignty is an aspect of grace as in power as in “Your Grace” (benevolent leadership) and “Your Sovereign Grace” (power modulated by grace/ethical consideration). Grace as in individual freedom(s) and systemic free flowingness are the monetary and economic policies that are necessarily aligned with a philosophy of Grace/graciousness. Everything proceeds from conscious awareness, thought, mind, philosophy. The broader, more inclusive and more ethical the philosophical concept the more translatable its aspects to Life and Living. Modernity like the Classical period before it has become way too unbalanced and biased, and an integration, a modern, natural economic re-integration of the classical concepts is necessary because the neo-classical sysnthesis was/is a false/incomplete one.

Thank you Neil Wilson. I do not see the connection between the system being insured and the central bank being the only one that can create money.

I do see that there will be less usury (interest payed) which means more money in the economy that will hopefully end up in the pocket of consumers. However, the con is that the commercial banks will be limited in how many loans they can issue. This is were I wonder about the effects on the economy.

Buyer Beware,

I envision a tri-level Financial and Banking system wherein ultimate and initial money creation is only from a sovereign national governmental agency which also has a philosophical and ethically mandated alignment with the natural concept of grace in all of its relevant economic and monetary aspects, and which also creates money for governmental purposes, but which governmental spending also is beholden to the same natural concept of grace. Then a structural Public Banking system which lends funds to commercial enterprise and to individuals and whose profits over and above the salaries and wages of its employees returns to the government and/or distributed back to the individual. Thirdly, Private Banking which is only allowed to aggregate but not leverage priorly earned and saved money which can be used for speculation with the complete and clear understanding that its consequences are ONLY the responsibilities of the parties involved. (Note: Speculative research could also be a function of the Public Banking system and receive funding from the government monetary agency so long as it passed the requirements that it lead to more resource efficient and traditional production but not some unhinged, wasteful and “money flowing uphill” financial legerdemain.)

“I do see that there will be less usury (interest payed) which means more money in the economy that will hopefully end up in the pocket of consumers.”

Interest is simply the wages of bankers, and bankers buy things just like the rest of us. Similarly profit is simply the wages of capitalises and they buy things like the rest of us.

There is no change in the of loan issue between an in specie and an insured system. It is determined entirely by the price level of the funding cost of banks on the liability side and any restrictions in what can be lent on the asset side.

As I said, nothing fundamental changes.

You can put up the price of loans and increase the amount of government spending today if you wanted ‘less interest’ to be paid to bankers.

Thank you for your patience in discussing this.

Re: Steve. The banks could be doing this now. I don’t trust them to all of a sudden begin doing what is for the good of their customer. I am afraid that this is yet another maneuver to find new avenues to “trim” profits.

Re: Neil Wilson. If the banker spent the money in the same community in a manner that put the money back into the pockets of the person paying back the loan, then, it would be neutral. However, the money goes to head office in a large hub where it is paid as a dividend to shareholders and is put into the market to buy more shares (and is lost to the economy) or worse offshored in bid to avoid paying tax. In my mind, very little of the money ends up circulating in the economy, which is what is contributing to the problem. Banks should guarantee that the money received from a community stays in that community. Otherwise, they are sucking money out of the economy.

Bill,

I’m not fundamentally in disagreement with your analysis but I do sometimes muse on the point of banks not lending out their reserves.

Just to conduct a thought experiment: Suppose we actually compelled banks to lend out their reserves. ie Suppose we insisted that banks not just edit the numbers in our accounts when they made loans but actually lend out bundles of real cash. RBA issued Aussie dollar notes, or BoE pound notes or whatever.

It wouldn’t make any difference at all. Either the borrowers would want their loans as cash, as they can probably have now if they want to, or if they don’t, they’d just deposit the pile of newly lent cash back into their bank accounts.

“Banks should guarantee that the money received from a community stays in that community”

It does. Within every currency zone, the money always stays within that currency zone. It can’t go anywhere else.

If people save, then you simply offset that paradox of thrift with lower taxation or extra government spending.

“it is paid as a dividend to shareholders and is put into the market to buy more shares (and is lost to the economy) or worse offshored in bid to avoid paying tax.”

Shareholders are usually pension funds who use the income to pay pension in payment to ordinary private pension holders. If you buy shares, then whoever sold those shares then has the money and will spend it. If you buy anything offshore then the FX system reflects the money back into your currency area – because they don’t use your type of money ‘offshore’.

So all those notions are misguided, and none of them affect the ability of the state to counteract the drain to financial savings.

The problem with banks is actually lending money for projects that do not improve the capital structure of the economy.

Buyer Beware,

Oh I completely agree they could be doing that now, but of course their own selfish self interest is is the stumbling block. My thinking assumes there must ultimately be a political fight to implement such things, but as thought/philosophy always precedes action and policy it is essential to have both the philosophy and policy clarified and agreed upon for the fight during which the financial authorities will of course use every divide, compromise and conquer tactic as well as smear, slander, other more subtle ego-schism tactics and even war and assassination. All the more essential to educate, raise awareness, form alliances and discipline the mass social movement (as Bill has shown a political movement is too inherently fractious and ego involved to be an effective tool of reform) necessary to herd the entirety of the political apparatus toward the most comprehensive solutions.

What need for government deposit insurance when ALL fiat users, including individuals, could have risk-free accounts and transactions at and via the central bank, respectively?

Because of the need for endogenous money creation? Via bank credit? But:

a) even fully private banks with fully voluntary depositors can extend SOME credit though borrowing short to lend long is risky.

b) shares in equity, common stock, is an endogenous money form that requires no government privileges, that shares wealth and power rather than concentrate them.

Because there is not enough fiat (bank reserves and physical cash) to go around? But that’s a simple problem to remedy via a properly metered and equal distribution of new fiat to all citizens plus a temporary* requirement that new bank loans be the lending of actual fiat from the lending bank’s central bank account to the borrower’s central bank account.

*till the metered bailout is accomplished and commercial banks become, as they always should have been, 100% private with 100% voluntary depositors.

F. Beard,

My tri-level banking and money system and dividend and retail discount policies are exactly designed to do the things you say, excepting the structural Public Banking which is also governed by the sovereign central bank would replace private banking for the most part. It would also satisfy Neil’s desire to see loans go for projects that improve the capital/productive structure of the economy instead for wasteful and vice ridden financialization. Private control of the money system in a flawed and already privately power coalesced world is doomed to fail. Of course government as we all know can be even more tyrannical than mega-corporate and financial tyranny, but that is why the directly distributive policies of a universal dividend and retail discount that are perfect reflections of grace as in free gifting, and which by definition are both individually freeing and enabling of systemic free flowingness are necessary. A philosophy of freedom, policy that frees and the actual effect of freedom in the spacio-temporal universe. A = A= A. This must be our underlying logic. And of course all of this could also include things like a job guarantee so long as it was completely optional so that neither the business community nor the Banking system could use it to dominate in any way. Of course if the money system was truly sovereign and also governed by the policies of freedom such dominating actions would become immediately obvious as out of alignment with gifting and freedom.

@ Neil,

If people save, then you simply offset that paradox of thrift with lower taxation or extra government spending

That’s theory but I would disagree with “simply”.

There’s still a problem if the savers are our overseas suppliers. If they want to save, they buy lots of gilts to force up the value of the pound so we can all afford lots of lovely imports. If they don’t want to save at all they don’t buy any gilts and may even cash in the ones they have so the pound falls and the UK has to earn its living from selling real goods and services. We don’t have any control over that.

That’s fine if the currency movements are relatively slow and predictable but companies often have to make investment decisions based on their projected profitability years into the future. American companies do have a significant advantage in that respect. As the US$ is the world’s dominant currency there is one less variable to be be concerned about.

So whereas it is right to say that currencies shouldn’t be pegged to another currency, there is also a case that they shouldn’t be allowed to vary too much too quickly. One way to avoid too much variation is to have a policy on trade which would set a limit to the allowable trade imbalance to something like 3% of GDP. There’s too much reliance on imports in the UK right now.

That means the Gilt traders in London make a healthy living but steel workers in Redcar make no living at all.

Peter, you are still viewing the whole world as acting as one and against the UK. Export led nations need to export or their economy collapses. Remember by buying imports the UK employs people in China and buys goods that otherwise wouldn’t get made. Currency wars are a bad idea.

“One way to avoid too much variation is to have a policy on trade which would set a limit to the allowable trade imbalance to something like 3% of GDP. There’s too much reliance on imports in the UK right now.”

I agree that reducing *reliance* on imports is a good idea. This makes as much sense as imposing limits on a 3 per cent of “GDP” deficit limit in a closed economy.

The dynamics of a currency is that you have to find somebody to sell it to and you have to settle. What you find then is that the liquidity within the market is self-restricting. Unless you have a central bank or other banks prepared to play patsy.

The way you fix that by stopping the banks playing patsy in the currency market and restricting emergency FX liquidity to needed goods and services. So the central bank *never* buys its own liabilities in the FX market. What it does is settle invoices via the banking system. Just like other asset side discipline.