Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – December 19, 2015 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Assume that a nation is continuously running an external deficit of 2 per cent of GDP. In this economy, if the private domestic sector successfully saves overall, we would find:

(a) A fiscal deficit.

(b) A fiscal surplus.

(c) Cannot determine because we would need to know the scale of the private domestic sector saving as a % of GDP.

The answer is Option (a) – A fiscal deficit.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

Expression (1) tells us that total income in the economy per period will be exactly equal to total spending from all sources of expenditure.

We also have to acknowledge that financial balances of the sectors are impacted by net government taxes (T) which includes all taxes and transfer and interest payments (the latter are not counted independently in the expenditure Expression (1)).

Further, as noted above the trade account is only one aspect of the financial flows between the domestic economy and the external sector. we have to include net external income flows (FNI).

Adding in the net external income flows (FNI) to Expression (2) for GDP we get the familiar gross national product or gross national income measure (GNP):

(2) GNP = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI

To render this approach into the sectoral balances form, we subtract total taxes and transfers (T) from both sides of Expression (3) to get:

(3) GNP – T = C + I + G + (X – M) + FNI – T

Now we can collect the terms by arranging them according to the three sectoral balances:

(4) (GNP – C – T) – I = (G – T) + (X – M + FNI)

The the terms in Expression (4) are relatively easy to understand now.

The term (GNP – C – T) represents total income less the amount consumed less the amount paid to government in taxes (taking into account transfers coming the other way). In other words, it represents private domestic saving.

The left-hand side of Equation (4), (GNP – C – T) – I, thus is the overall saving of the private domestic sector, which is distinct from total household saving denoted by the term (GNP – C – T).

In other words, the left-hand side of Equation (4) is the private domestic financial balance and if it is positive then the sector is spending less than its total income and if it is negative the sector is spending more than it total income.

The term (G – T) is the government financial balance and is in deficit if government spending (G) is greater than government tax revenue minus transfers (T), and in surplus if the balance is negative.

Finally, the other right-hand side term (X – M + FNI) is the external financial balance, commonly known as the current account balance (CAD). It is in surplus if positive and deficit if negative.

In English we could say that:

The private financial balance equals the sum of the government financial balance plus the current account balance.

We can re-write Expression (6) in this way to get the sectoral balances equation:

(5) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAD

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector.

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to add financial assets.

Expression (5) can also be written as:

(6) [(S – I) – CAD] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAD] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

So what economic behaviour might lead to the outcome specified in the question?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down. The reference to the specific 2 per cent of GDP figure was to place doubt in your mind. In fact, it doesn’t matter how large or small the external deficit is for this question.

Assume, now that the private domestic sector (households and firms) seeks to increase its saving ratio and is successful in doing so. Consistent with this aspiration, households may cut back on consumption spending and save more out of disposable income. The immediate impact is that aggregate demand will fall and inventories will start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms will soon react to the increased inventory holding costs and will start to cut back production. How quickly this happens depends on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But if the households persist in trying to save more and consumption continues to lag, then soon enough the economy starts to contract – output, employment and income all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption multiplies through the expenditure system as workers who are laid off also lose income and their spending declines. This leads to further contractions.

The declining income leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

So the initial discretionary decline in consumption is supplemented by the induced consumption falls driven by the multiplier process.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further towards and eventually into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public fiscal balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

If the private sector persists in trying to increase its saving ratio then the contracting income will clearly push the budget into deficit.

So if there is an external deficit and the private domestic sector saves (a surplus) then there will always be a fiscal deficit. The higher the private saving, the larger the deficit.

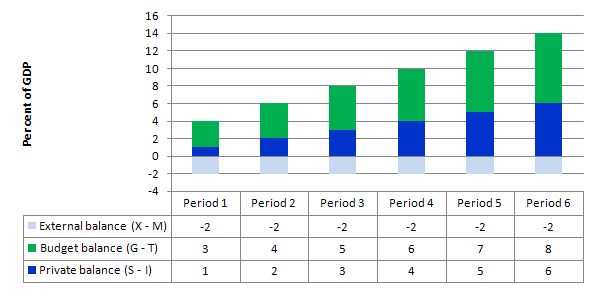

The following Graph and related Table shows you the sectoral balances written as (G-T) = (S-I) – (X-M) and how the fiscal deficit rises as the private domestic saving rises.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 2:

Given that government bonds constitute a component of non-government sector wealth, that sector’s net worth rises if the government issues bonds to match its deficit spending.

The answer is False.

The mainstream macroeconomic textbooks all have a chapter on fiscal policy (and it is often written in the context of the so-called IS-LM model but not always).

The chapters always introduces the so-called Government Budget Constraint that alleges that governments have to “finance” all spending either through taxation; debt-issuance; or money creation. The textbooks fail to convey an understanding that government spending is performed in the same way irrespective of the accompanying monetary operations.

They claim that money creation (borrowing from central bank) is inflationary while the latter (private bond sales) is less so. These conclusions are based on their erroneous claim that “money creation” adds more to aggregate demand than bond sales, because the latter forces up interest rates which crowd out some private spending.

All these claims are without foundation in a fiat monetary system and an understanding of the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt helps to show why.

So what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a fiscal deficit without issuing debt?

Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

There is no sense that these debt sales have anything to do with “financing” government net spending. The sales are a monetary operation aimed at interest-rate maintenance. So M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. It is this result that leads to the conclusion that that deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk. It does not.

So in terms of the specific question, you need to consider the reserve operations that accompany deficit spending. Like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management as explained above. But at this stage, M1 (deposits in the non-government sector) rise as a result of the deficit without a corresponding increase in liabilities. In other words, fiscal deficits increase net financial assets in the non-government sector.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

While fiscal deficits rise due to the operation of the automatic stabilisers, these effects work in a counter-cyclical fashion to ensure that the government fiscal balance returns to its appropriate level once growth resumes.

The answer is False.

The factual statement in the proposition is that the automatic stabilisers do operate in a counter-cyclical fashion when economic growth resumes. This is because tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this increases when there is an economic slowdown.

The question is false though because this process while important may not ensure that the government fiscal balance returns to its appropriate level.

The automatic stabilisers just push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit when GDP growth declines and vice versa when GDP growth increases. These movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

We also measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

This decomposition provides (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances. The fiscal components are adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal outcome is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal outcome into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

In some of the blogs listed below I go into the measurement issues involved in this decomposition in more detail. However for this question it these issues are less important to discuss.

The point is that structural fiscal balance has to be sufficient to ensure there is full employment. The only sensible reason for accepting the authority of a national government and ceding currency control to such an entity is that it can work for all of us to advance public purpose.

In this context, one of the most important elements of public purpose that the state has to maximise is employment. Once the private sector has made its spending (and saving decisions) based on its expectations of the future, the government has to render those private decisions consistent with the objective of full employment.

Given the non-government sector will typically desire to net save (accumulate financial assets in the currency of issue) over the course of a business cycle this means that there will be, on average, a spending gap over the course of the same cycle that can only be filled by the national government. There is no escaping that.

So then the national government has a choice – maintain full employment by ensuring there is no spending gap which means that the necessary deficit is defined by this political goal. It will be whatever is required to close the spending gap. However, it is also possible that the political goals may be to maintain some slack in the economy (persistent unemployment and underemployment) which means that the government deficit will be somewhat smaller and perhaps even, for a time, a fiscal surplus will be possible.

But the second option would introduce fiscal drag (deflationary forces) into the economy which will ultimately cause firms to reduce production and income and drive the fiscal outcome towards increasing deficits.

Ultimately, the spending gap is closed by the automatic stabilisers because falling national income ensures that that the leakages (saving, taxation and imports) equal the injections (investment, government spending and exports) so that the sectoral balances hold (being accounting constructs). But at that point, the economy will support lower employment levels and rising unemployment. The fiscal outcome will also be in deficit – but in this situation, the deficits will be what I call “bad” deficits. Deficits driven by a declining economy and rising unemployment.

So fiscal sustainability requires that the government fills the spending gap with “good” deficits at levels of economic activity consistent with full employment – which I define as 2 per cent unemployment and zero underemployment.

Fiscal sustainability cannot be defined independently of full employment. Once the link between full employment and the conduct of fiscal policy is abandoned, we are effectively admitting that we do not want government to take responsibility of full employment (and the equity advantages that accompany that end).

So it will not always be the case that the dynamics of the automatic stabilisers will leave a structural deficit sufficient to finance the saving desire of the non-government sector at an output level consistent with full utilisation of resources.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

it’ so easy to get the wrong end of the stick if you are not great at combinatorial though processes -with the first question the positive number of 2% of GDP lulled me into thinking ‘surplus’ so I fell into Bill’s ‘trap.’ it’s great that you (Bill) keep repeating the basics for people like me-one day I might be a bit more attentive!

Excuse my naivety here Bill – but what got me confused about Question 2 was the element of interest paid on bonds-wouldn’t these payments increase private net assets? Or possibly reduce them if the yield was lower than inflation? I suppose what I’m trying to say is: isn’t the interest payment on bonds a net asset (or loss with very low yields?).

Simonsky at 9.44.

I agree. This question has been posed before and someone asked the same question which, I don’t think, was answered.

IMV, one of the reasons why the gap between the rich and the poor (or the 99 per cent of us, not even necessarily the poor as such) is that governments insist on issuing debt to fund their deficits. They then pay interest on the debt so the bond-holders get richer. Perhaps someone might want to refute this argument.

So I checked “true” even though I knew the answer would be “false” and only got 2 out of 3.

Also IMV, inflation doesn’t come into it because wealth is measured in the unit of account, so it doesn’t matter what actual goods you can buy with your wealth. It only matters when monetary wealth is turned into goods or real estate.

Bill,

Re your response to Simonsky, I accept that income from bond interest is a flow. But what do the recipients do with the income? Presumably buy more bonds. Indeed, more bonds will be available as the government has to issue them to pay the interest.

So this all adds to the stock of wealth owned by the super-rich. Given, of course, that many of the bondholders are our pension funds.

Bill,Nigel—I can see how flows horizontally might not add to net wealth but in the case of bond interest-isn’t this a vertical flow-so a net asset of the private sector?

(I think my brain is now juggling with: vertical/horizontal/stock/flow)

Consider that bonds can be issued at zero or even negative interest yields.

In any case the question is whether the act of issuing bonds adds to private sector wealth, not whether subsequent acts (such as paying interest) might do so.

With regards question 3 the matter seems to hinge on the use of the word appropriate, I.e. Whether the non-cyclical component is Bill’s idea of appropriate or the government’s.

Brendanm

Semantics really. It’s why I hate quizzes – you can’t phrase the question so that it covers all possibilities, so the answer is usually arguable. But I’ll concede your point. Nevertheless the issuance of all these Treasury bonds is making the rich richer and not doing anything to make the rest of us a bit richer (or less poor).

That’s not to say I buy the various conspiracy theories that are going around. It behoves the rich to maximise their wealth, whilst at the same time trying to ensure it doesn’t diminish. Government bonds are a good way of doing the latter. Why wouldn’t you?

Bill/Nigel/Brendan,

Warren Mosler, says this of bonds: “So in that sense,” Mosler says, “issuing securities means paying higher rates than the overnight rate. It is a spending increase and has an inflationary bias by adding net financial assets to the system.” – See more at: http://dailyresourcehunter.com/what-the-fed-is-really-doing-to-your-money/#sthash.JhlpFWqa.dpuf

How does this square with Bill’s response above-it seems Mosler is saying that a net financial asset IS created with the interest (unless I’m confusing concepts which I’m prone to!).

Dr. Mitchell, regarding question #2, will the issue of a government bond deprive the private sector of income because the portfolio swap deprives the private sector of bank deposits that could have been spent to create income for others via the spending multiplier process?

When the government deficit spends, I understand that the original target of the government deficit spending receives the benefit of the income, but the bank deposit gives the recipient the opportunity to spend the money (or the bank to loan out the money for another to spend), adding to aggregate demand via the spending multiplier process. If the recipient (or anyone else in the private sector) buys a government bond, that spending multiplier could not occur, since the deposits are no longer available to spend.

Or will the secondary spending simply occur using government bonds instead of cash? I think that most bonds are not used (or accepted) as a cash substitute, but rather used for savings or for financial speculation.

I am reminded of the policies of the US Federal Government during WWII, who aggressively promoted Liberty Bonds to finance the war effort. One result is that the purchases transferred most household savings into highly illiquid government securities and removed secondary spending from the economy. This created fiscal ‘space’ for the government to increase production of war materiel without contributing more to inflationary pressures.

Thanks,

Joel