The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Finland – more austerity is not the answer

Finland has been one of the Eurozone nations taking a hardline on Greek austerity and have consistently refused to support on-going bailouts of Greece. At the weekend, Finland went to the polls and tossed out the incumbent government and put in its place a centrist party that stood on a platform of a wage freeze and further spending cuts, allegedly to restore Finland’s competitive position. If that prospect wasn’t bad enough, the Centre Party will have to enter a coalition with the party that came second in the polls – the Finns Party, which is a ragbag anti-immigration group that wants Greece kicked out of the Eurozone. It is possible that Finland’s Parliament will not support any further European Union bailouts for Greece. Apparently Finn’s are buying the line that further and intensified austerity is necessary because of rising labour costs have undermined Finland’s capacity to compete in international markets as the demise of Nokia, so the narrative goes, illustrates. The last thing that Finland needs right now is more austerity.

Finland was previously considered a model economy in terms of competitiveness. The following graphic taken from the latest World Economic Forum’s – Global Competitiveness Index 2014-2015 – places Finland at number 4 in the world.

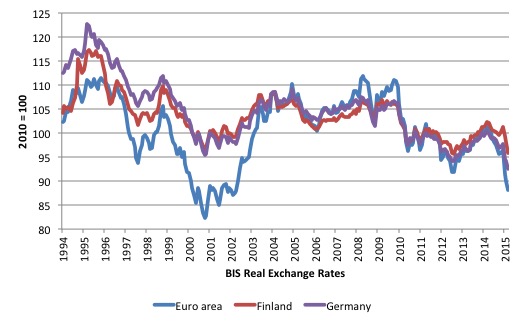

The following graph uses the data from the Bank of International Settlements monthly Effective exchange rate indices – which are published from January 1994 to February 2015.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS ‘real effective exchange rate indices’ (REER) adjust nominal exchange rates with other data on domestic inflation and production costs.

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness …

If the REER rises (falls) then we conclude that the nation is less (more) internationally competitive.

The following graph shows the movement in real effective exchange rates from 1994 to March 2015 for the Eurozone in total (blue line), Finland (red line) and Germany (purple line).

The data shows that following the introduction of the euro, the international competitiveness of Finland and Germany increased.

Following the crisis, the general tendency has been for real effective exchange rates to decline, with Finland and Germany in lockstep until 2014.

Since the beginning of 2014, Eurozone competitiveness has declined by 11.5 per cent while Finland’s REER decline by 5.3 per cent and Germany’s by 6.9 per cent.

So there has been some loss of international competitiveness, largely due to an overvalued Euro, but the relative internal cost position of Finland remains superior to Germany.

Please read my blog – Eurozone unemployment – little to do with international competitiveness – for more discussion on this point.

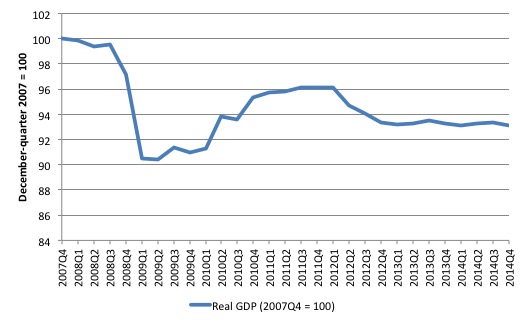

But the fact is that Finland has been mired in recession since the second-quarter 2012. Since that quarter, it has recorded only three positive quarters of growth and in the most recent data release it contracted by 0.2 per cent (December-quarter 2014).

Its peak real GDP came in the fourth-quarter 2007, and 7 years later it still was 6.87 percentage points below that level of output.

The following graph tells the story. It is an index of real GDP (2007Q4 = 100). So falls in the index indicate negative real GDP growth and flattening slopes indicates slowing growth or contraction.

The crisis hit hard and as the fiscal deficit expanded (via automatic stabilisers and some discretionary stimulus), real GDP growth resumed until late in 2011 as the austerity madness took hold.

From the first-quarter 2012, it has been largely downhill.

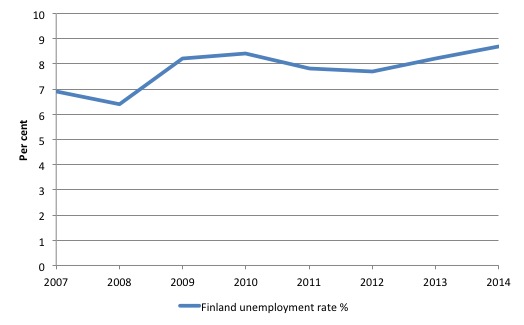

The real GDP history is reflected in the evolution of the unemployment rate as shown in the next graph. With real GDP growth in near constant recession over the last three years, the unemployment rate has risen without end at present.

Clearly, the policy approach adopted by the Finnish government since 2012 hasn’t worked and the regime deserved to be booted out of office.

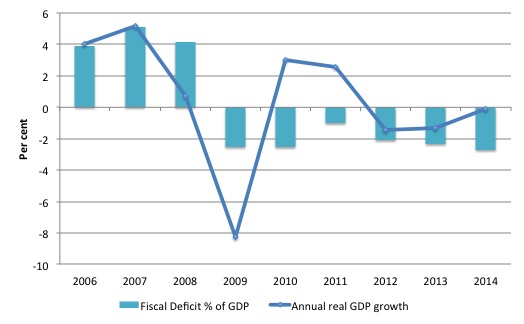

The following graph tells you a lot if you combine it with other knowledge of what was happening at the time. It shows annual growth in real GDP for Finland (per cent) from 2006 to 2014 (using Eurostat data). The jade columns show the fiscal deficit (-ve) as a per cent of GDP over the same period.

Going into the GFC, Finland was running fiscal surpluses and growing fairly strongly on the back external surpluses (the Nokia dominance).

When the GFC hit, the fiscal surpluses vanished – unsurprisingly given that real GDP contracted by 9.7 percentage points between the fourth-quarter 2007 and the second-quarter 2009.

The increasing fiscal deficits supported a relatively speedy return to growth in 2010 but discretionary attempts to reduce the fiscal deficit in 2010-11 saw the growth slow, then vanish and after one year of lower fiscal deficits, Finland once again saw its fiscal deficit increase.

The reason is obvious. By going along with the austerity myth, the Finnish government not only undermined the growth of the economy but also thwarted its ill-considered ambitions to return to fiscal surplus quickly.

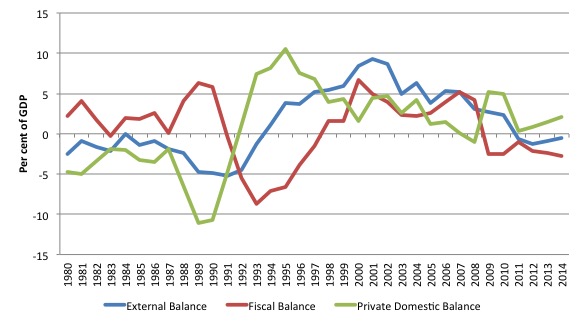

To get a longer view of what was going on, the following graph shows the sectoral balances for Finland from 1980 (using IMF WEO data).

To learn about the sectoral balances and their interpretation please see the following blogs:

They are accounting relationships derived from the national accounts and capture the external balance (blue line), the fiscal balance (red) and the private domestic balance (green).

The Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) accounting statement that government deficits (surpluses) must equal non-government surpluses (deficits) is the starting point. The non-government sector is further decomposed into the external sector and the private domestic sector.

So if the external sector is in surplus the nation enjoys net income boost whereas if the external sector is in deficit, it is draining spending and income from the domestic economy.

If the private domestic sector is in surplus it means it is saving overall or spending less than its income and vice versa.

The graph expresses these balances as a percent of GDP.

The graph shows that in the period leading up to the crisis, the external sector surpluses (boosting local spending) were sufficient to allow the government to run surpluses without undermining the overall saving desires of the private domestic sector.

Once the crisis struck and the decline in export revenue reduced the external surplus and the sharp increase in the fiscal deficit supported the rise in private domestic saving overall (as caution became the concern for households and firms).

More recently, with the external sector draining spending via deficits (largely due to the crisis in Russia and the impact of Eurozone austerity on export markets) and the private domestic sector has once again decided to increase its overall saving, the fiscal deficit has had to increase.

Any attempt to impose increased austerity in an attempt to return the fiscal position to surplus would be disastrous for the Finish economy.

The economy clearly needs a substantial fiscal stimulus to support economy in the face of private domestic caution and the lax trade sector.

The movements in REERs do not support the view that excessive wage costs have damaged Finish competitiveness.

Further, using the AMECO database from the European Commission, Finland’s Real Unit Labour Costs increased in the period 2000-2010 by 5.51 per cent on the back of some hard won wage increases.

Over the same period, Germany’s RULCs fell by 5.2 per cent but nations such as Ireland saw their RULCs rise by 7.9 per cent, Greece 7.6 per cent, Italy 6.9 per cent, and Luxembourg 8.4 per cent.

Since the crisis (2010-14), Finland has seen only modest increases in RULCs (1.6 per cent) compared to Germany 1.8 per cent, France 1.4 per cent, Italy 0.7 per cent, and Netherlands 4 per cent.

Obviously, RULCs have fallen dramatically in Ireland between 2010-14 (6.1 per cent), Greece 8.6 per cent, Spain 4.9 per cent, Cyprus 10.2 per cent, and Portugal 5.3 per cent.

Finland relied on an export-led growth strategy which stumbled largely because the rest of the world stopped buying imports for a time.

That reality will not return if it scorches the domestic economy with harsh internal devaluation (real wage cuts etc) and sharp public spending cuts.

Finally, the demise of Nokia has been a major loss to the Finnish economy. While I am not an industrial economist, expert in the whys and wherefores of that particular firm, the decline of the telecommunications company and its takeover by Microsoft is not related to excessive wages or the fiscal deficit.

Nokia did not lose market share because wage rises undermined its ability to compete.

This article (September 4, 2013) – How bad calls led to Nokia’s demise – is a reasonable depiction of what happened. I have read a lot of articles about the demise of Nokia in recent years. This one is representative of what might be considered a consensus view.

As you will note the demise had little to do with wages.

1. “the Finnish phone giant grew dangerously intoxicated on its own success during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Having ridden so high for so long, it is perhaps no surprise that a degree of complacency and arrogance crept in just as had happened at Kodak and Motorola”.

2. “Such success intoxication left Nokia highly vulnerable to disruption, which soon came in the form of the smartphone.”

3. “Nokia was a company who fell prey to geographic isolation” (wrong location in the US – no synergies etc)

4. “a third causal factor in Nokia’s demise was its stifling levels of bureaucracy” – which saw its management fall behind “the curve”. In particular, it refused to introduce “color touch screens, mapping software and e-commerce functionality” and ignored its technical engineers who had “designed a wireless-enabled tablet computer long before the iPad was even imagined”.

Its research department was “disconnected from the company’s operations departments who were responsible for bringing devices to market”.

5. “Nokia’s example is a case in point of how critical it is to anticipate shifts in the marketplace and adapt before your hand is forced”.

That sounds like a management failure to me – rather than greedy trade unions undermining the competitiveness of an able company.

Various case studies I have read about the demise of Nokia and other large companies reinforce the idea that the management becomes trapped in their own Groupthink which patterns their behaviour and insulates them from reality. They become their own legends.

Conclusion

While the previous Finish government deserved to be thrown out of office, things will get worse if the new government adopts an even harsher austerity stance in the hope that Finland will somehow recapture its export-led powerbase.

The austerity will thwart any attempts to promote industrial innovation in that nation and just become part of a race to the bottom – where people (and firms) usually drown.

Stocks and Flows Paul Krugman

Paul Krugman wrote a quick blog (April 19, 2015), after his visit to Greece – Notes on Greece – where he shows the huge fiscal shift that has occurred under the vicious austerity regime imposed by the Troika and the huge decline in “nominal private-sector labor costs” relative to the euro average.

He considers this is enough information to allow for this conclusion:

You can make a pretty good case that the costs of this adjustment were so large that Greece would have been better off exiting the euro in 2010. You can make an even better case that Greece would have been much better off if it had never joined in the first place. But at this point these are sunk costs. If Greece can negotiate a halfway reasonable compromise, one that more or less pauses further austerity, it’s hard to see that the risks of exit would be worth it.

I continue to disagree with that position.

Sunk costs are defined by economists as “a cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered”.

The relevance of sunk costs in microeconomics is that they should be disregarded when making decisions about future investment expenditure because they are gone for good and will not affect the future costs that might be incurred.

This mainstream view is challenged by behavioural studies which suggest that in the real world humans do not act in a ‘rational’ way as defined by economists because they are concerned about other issues (loss aversion) and are subject to cognitive biases.

But that is not the point of my criticism of Paul Krugman’s gratuitous conclusion about Greece.

While the adjustments costs – lost output and income never to be regained – might be considered in the class of sunk costs – and so there is nothing you can do about it now, there are still massive stocks associated with these dramatic flow costs (the lost income and spending) remaining.

For example, a most relevant ‘stock’ is the mass unemployment, which is at 26.5 per cent (2014), the highest in the Eurozone. It doesn’t matter that the nation has vandalised its prosperity by getting the primary fiscal balance back into surplus and is therefore according to Krugman’s logic operating within the rules of the Eurozone.

The decision as to the nation’s status within the Eurozone should be made on the basis of which option will get it back to full employment in the shortest possible time without compromising human rights and maintaining the job protections etc.

Sure enough, Greece has been bashed into a sorry state by the Troika bullies and one might think it couldn’t get any worse. But the stock of unemployment, for example, will linger for years to come if the Greek government stabilises the economy within the rules of the Eurozone.

Krugman might think that such stability will not impose any further major losses. But the intergenerational damage of the high youth unemployment is going to cause massive costs for decades to come unless it is eliminated quickly.

Even if the new Greek government negotiates a “compromise … that pauses further austerity” it will be unable to reverse the high unemployment and related damage quickly.

What Greece needs is a massive fiscal stimulus and introducing a major public works program with a Job Guarantee would be an excellent start.

It cannot do that under existing Eurozone rules and there is no sign that those rules will change any time soon.

I realise Syriza politicians and commentators like Paul Krugman and James Galbraith argue that Greece can restore prosperity and stay within the Stability and Growth Pact rules as long as the – European Investment Bank – provides a huge funding boost to Greece for infrastructure development.

That likelihood is very small.

The infrastructure package announced by the new European Commission boss when he took over in January 2015 was pitiful compared to the scale of the problem the policy elites have created through austerity.

So I think Paul Krugman needs to rethink his position before pronouncing that Greece is now better off within the Eurozone given it cannot hardly be bashed any harder than it has.

There would be huge costs involved in exiting the monetary union. But I still consider they would be less than the on-going costs of the massive entrenched unemployment pool, especially the youth unemployment.

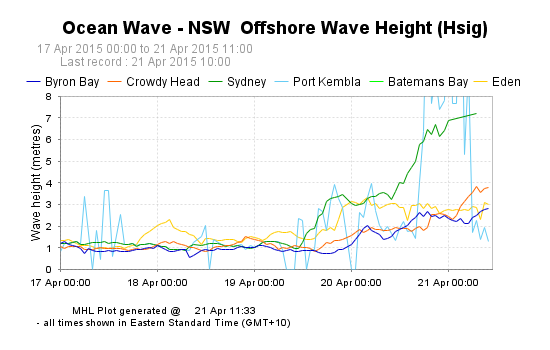

Storms in NSW

The East Coast of NSW (where I live mostly) is currently being lashed by severe storms which are bringing down trees, blowing roofs away, flooding rivers and roads, and causing general havoc. Several people are dead already. Two large trees outside my homeare down this morning. Railways are closes, schools are closed and the University closed today due to the chaos.

Parts of NSW have endured the heaviest rainfall for 100 years.

The barometric pressure at the Stockton Bridge, across the Hunter River (mouth at Newcastle) has dropped to 1008 millibars which means we are in an intense low pressure system.

This incredible graph comes from the – Manly Hydraulics Laboratory – which is part of the NSW Government’s Public Works Department.

The wave height in metres at Port Kembla (just south of Sydney) went off the scale of their recording instruments – more than 8 metres.

The MHL says:

To provide deepwater wave data, the buoys are typically moored in water depths between 70 and 100 metres, between 6 and 12 kilometres from the shoreline.

They report that two of their buoys have gone adrift in the seas.

Trying times when you look out the window and see large trees being blown almost to horizontal.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Crickey. 1008 millibars is a bit of a cloudy day with a few showers here.

Stay safe!

Dear Bill

Besser ein Ende mit Schrecken als ein Schrecken ohne Ende. If The Greeks keep the euro, they’ll have ein Schrecken ohne Ende. If they leave the eurozone, they’ll have ein Ende mit Schrecken, but after that, it should be going upward for them.

The Greek debt is 175% of GDP. With a primary surplus of 3% and no GDP growth, they’ll need 58 years to pay off their debt, without considering interest. With rapid growth, it would be a different story, but they aren’t likely to grow if they stay within the euro. If they imposed a moratorium on all debt payments for 5 years and left the euro, then in the end the creditors would be better-off too.

Suppose that Peter owes me a large sum. He needs a new car to drive to work. He can’t at the same time make payments for a new car and service his debt to me. In such a case, it would be in my own interest to let him suspend his debt servicing so that he can get his new car and keep his job. Once the car is paid off, he can resume his debt servicing to me. Greece can be compared to Peter.

You wrote that Greece needs a major public works program. Is that true? Is there a shortage of public works in Greece? In my view, a government should only spend money on infrastructure if there is a shortage of it. If the level of infrastructure is adequate, then no money should be spent on it. In that case, it is better to let individuals spend the extra money coming from the fiscal stimulus as they fit. That of course would mean that some of the fiscal stimulus would leak into imports.

Regards. James

Austerity kills, it is as simply put as that.

It is for the rich to become richer, and the poor to starve.

Forbes’ article said it right:

Currency unions such as the European Monetary Union can only work in the long-run if wealthier states directly subsidize poorer states with no strings attached.

For example, U.S. states such as New Mexico and West Virginia have consistently received more funds from the federal government than they collected in taxes.

These ‘state subsidies’ were supported by funds from New York and Delaware (Washington DC national (federal) government).

http://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2015/04/03/what-to-buy-if-greece-exits-the-euro-zone/

PLAID CYMRU IN WALES

Said the truth of the austerity obsessed UK Tory government, about to become a dictatorship in a caretaker government after a hung parliament from May.

Austerity failed to deliver.

Deficit has not been eliminated.

UK’s debt is rising and is over £1.4 trillion.

The UK has lost its coveted ‘Triple-A’ credit rating.

NO SOCIETY IN HISTORY HAS EVER SURVIVED LEAVING ITS POOR TO STARVE

The SNP in Scotland have declared they will ensure the UK ends austerity.

PLAID CYMRU AND SNP and even tiny MEBYON KERNOW IN CORNWALL

Gave nearly 100 MPs opposition, which can add the 8 DUP from Ulster.

But in fact the media silence about the parties 6th on the ballot sheet in England, has stopped the UK from galloping headlong into a dictatorship of a TORY / LABOUR / LIB DEM coalition, with just these 100 MPs from the Celt regions as an opposition, but who will also have to negotiate with the dictatorship in a support and confidence manner.

The 6th parties on the ballot sheet in England could have brought in, with the Celt regions, over 250 anti austerity MPs into a formal majority government, with whatever is left of Labour, to turn that party anti austerity.

I fear now that all that will happen is a revolution against the coming dictatorship.

Shame the media stopped the people’s will and did not do their job of informing the public and so disenfranching 75 per cent of all voters in the UK.

James, I thnk that perhaps Streit might be a better term than Streichen with respect to the present Greek context.

Finland invited Sweden’s former neoliberal Minister of Finance Anders Borg right after he lost his position due to the election 2014, to give them advice on how to run a country successfully.

The myth set by neoliberals is that Anders Borg is exceptionally good at economics (he did not complete his bachelor degree) , and the proof they constantly bring up is the way he handled the the finance crisis which hit Sweden about 2008.

But the reason Sweden managed as well as it did was because of the size of its welfare state which Anders Borg earlier had begun to dismantle when he came to powers 2006. Had Anders Borg had more time to dismantle it further than he did up to the crisis 2008 things would of course been worse. But luckily he could rely on what was left of the automatic stabilisers, although cripple due to his earlier policies.

Anders Borg’s real actions during the crises was to do _nothing_ in order to “save” the money in case banks would need them, at a time when industry bargained for lowering wages to “save” jobs due to lack of incoming orders, which BTW our present prime minister (a social democrat) thought was a splendid idea (he was a union boss back then), making the crisis worse that had to be.

Other than that he advocated that policy should be founded in good economic research, where he himself thought garbage like Reinhart and Rogoff’s Growth in a Time of Debt was top notch.

So if Finland is now bringing to life advice from this Swedish hack the future for Finland does not look promising.

“If that prospect wasn’t bad enough, the Centre Party will have to enter a coalition with the party that came second in the polls – the Finns Party, which is a ragbag anti-immigration group that wants Greece kicked out of the Eurozone.”

Centre party doesn’t have to enter a coalition with the Finns party. It depends about negotiations. Yes, it is probable that the Finns party are going to form a coalition with Centre party (and with 1-3 other parties), but it ain’t 100% sure yet.

In Finland the problem seems to be that there is some structural reforms which might be needed in longer run( and I personally think that public sector should be little smaller), and that some fiscal stimulation would be good. What makes it problematic is that parties that support structural reforms don’t support fiscal stimulation, and vice versa.

“If the REER rises then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive. ”

Right.

” Following the crisis, the general tendency has been for real effective exchange rates to decline, with Finland and Germany in lockstep until 2014.

Since the beginning of 2014, Eurozone competitiveness has declined by 11.5 per cent while Finland’s REER decline by 5.3 per cent and Germany’s by 6.9 per cent. ”

No, because REER decline means more competitiveness, Finland has actually fallen behind Germany in competitiveness.

“So there has been some loss of international competitiveness, largely due to an overvalued Euro, but the relative internal cost position of Finland remains superior to Germany. ”

Lately euro has been fallen in value agains USD for example: https://www.google.com/finance?q=EURUSD

and measures of competitiveness show an increase.

btw there is no way the tell if Finland is competitive or not from this sort of graph because they are indexed to 2010, and show only relative movements to that year. Who knows what situation was back then?

As far as I can tell this talk about lost competitiveness is about losing ground against Germany from 2007 to now.