I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Australia’s generosity to other nations is collapsing

There was a story in the Australian press (April 8, 2015) – ‘Impossible choices’ to be made as human cost of foreign aid squeeze measured – that not only exposes the deep flaws in economic reasoning that accompany neo-liberalism’s emphasis on austerity but also makes one ashamed to be Australian. The problem, however, is not Australian-specific. The neo-liberal paradigm rules the World at present and humanity generally is the victim, particularly those most disadvantaged in material terms. The cuts announced by the Australia federal government to our Overseas Aid Program in the next three years will be the largest shift in provision of aid in our history. The projected cuts are now starting to manifest in concrete terms as aid agencies start to cancel programs and lay off staff. Once again the myths of neo-liberal macroeconomics leads us to accept governments doing appalling things in our name.

The Fairfax article (linked in the introduction) reports that several aid agencies (such as World Vision) are now cutting aid programs:

… helping tens of thousands of poor people in developing countries because of the Abbott government’s swingeing cuts to foreign aid.

As an example cited, one of the poorest nations in the world, South Sudan, which is currently beset with “a devastating humanitarian crisis” will see a “$1 million education scheme … that was to benefit more than 11,000 people” scrapped due to Australian government funding cuts.

The journalist writes that:

Australia’s overseas aid budget has been a major casualty of the government’s efforts to repair the budget. Our assistance to the world’s poorest people will be slashed from its current level of around $5 billion to around $3.4 billion in three years’ time (at today’s prices). That will reduce Australia’s official aid contribution to just 22¢ out of every $100 of national income – the least generous ever.

He might have questioned the whole exercise but then when a journalist uses terms like “repair the budget” you know they are caught up inside the neo-liberal Groupthink.

The terminology “repair” is loaded. It assumes the fiscal balance is like a car that has broken down and needs to be fixed.

It further constructs a fiscal deficit as being a dysfunction and the larger the deficit the worse the repair job becomes.

The construction is invalid at the most elemental level.

What needs to be attended to in the Australian economy at present is the rising unemployment rate. The fiscal balance is a reflection of the extensive labour underutilisation in the sense that the flat employment growth and rising joblessness has undermined the tax base of the Federal government.

It is also a cause in the sense that if there is mass unemployment (that is, unemployment beyond the small amount associated with full employment – people moving between jobs etc) then Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tells us that the fiscal deficit is too low.

The first observation (reflection) is about the behaviour of the automatic stabilisers, while the second (cause) is about the discretionary policy choices made by government. Both impact on the fiscal balance.

But a rising deficit is not something that should be the target of policy. A deficit of 10 per cent of GDP might be appropriate under some conditions (relating to private spending and the external balance) just as a 2 per cent deficit might be appropriate under different conditions. At times, a fiscal surplus might be appropriate.

There is nothing linear and directional about it – up is not always good nor bad just as down is not always good or bad.

The head of World Vision emphasised what the mindless cuts in Overseas Development Aid (ODA) will mean:

I’ve found it personally devastating over the past few weeks to be forced into making impossible choices … How do you prioritise the importance of existing work in child protection, education, or community resilience in the face of major conflict, or life-saving health interventions?

The cuts to the aid budget are so great now, we can’t escape long term and devastating consequences in terms of lives, in terms of ongoing health issues or educational opportunities, for many communities throughout the world, the chance these programs would have given almost 2 million people, will never be regained in their lifetime …

I have been reading a new book today – Thieves of the State – by Sarah Chayes (2015) which argues that corruption in nations directly creates global insecurity. The author considers the Afghanistan Karzai government, a puppet of the US, to be a successful “vertically integrated criminal organisation”.

She argues that far from being failed states, many developing nations are extremely successful given the aim of these states is to channel largesse to the corrupt rich. Eventually, this corruption leads to groups like Boko Haram forming, which then is miscontrued as Islamic terrorism rather than a reaction to the corrupt states propped up by the western finance machine and the multilateral agencies such as the IMF.

The author’s argument is compelling.

While the US and its allies such as Australia think that democratising nations is about invading them militarily, blasting the hell out of all and sundry, and then propping up corrupt government which then act as conduits to siphon off the nation’s wealth and income flows to the elites, whoever they might be, the book demonstrates that this strategy breeds contempt and allows movements like Boko Haram to form.

Further cuts to aid where it supports the activities in poorer nations that we generally think are important for ‘states’ to undertake – public education and health, governance, etc – will only exacerbate these global instabilities.

Australia, now, has an appalling record in terms of ODA. And as it embraces the mindless fiscal austerity the record is set to get worse.

Historical context of ODA

In 1970, the 25th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations passed a – Resolution on Financial resources for development – (Paragraph 43) that said:

In recognition of the special importance of the role that can be fulfilled only by official development assistance, a major part of financial resource transfers to the developing countries should be provided in the form of official development assistance. Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.

The UN agreed that while “developing countries must, and do, bear the main responsibility for financing their development” it was still beholden on each “economically advanced country” to provide substantial resources by way of overseas development aid to assist nations that were less well-off.

Most recently, the – Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development – which emerged out of the Monterrey, Mexico meetings of the United Nations (March 18-22, 2002) said that (Paragraph 42) in the context that “a substantial increase in ODA and other resources will be required if developing countries are to achieve the internationally agreed development goals and objective” and:

In that context, we urge developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries …

The meeting also noted “that ODA will still fall far short of both the estimates of the flows required to ensure that the millennium development goals are met and the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product”.

You will also find the resolution re-affirmed at the – World Summit on Sustainable Development – which was held in Johannesburg, August 26-September 4, 2002.

This link allows you to learn about the history of the – The 0.7% ODA/GNI target.

The ODA/GNI ratio tells us how much the government of any country is allocating to ODA relative to the size of the economy (the nation’s total income).

There is a debate as to whether this ratio measures the generosity of a nation given that it doesn’t provide any measure of aid quality nor what happens to the aid once it is dispersed.

The latter point is very important given the extent of the corruption in many nations receiving the ODA and the discussion above relative to global insecurity.

OECD report

Yesterday (April 8, 2015), the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) released its latest – Development Update – which shows that:

Bilateral aid to the group of least developed countries was USD 25 billion, a decrease of 16% in real terms compared to 2013.

While this statistic has hit the headlines, one has to be a little cautious because it reflects “ower levels of debt relief, which was relatively high in 2013 due to assistance to Myanmar”.

Once we take that effect into account:

Excluding debt relief grants, ODA to the least developed countries fell by about 8%.

Still a hefty decline in real terms.

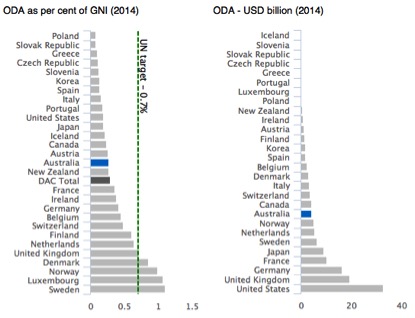

But while these shifts are damaging, the on-going disturbing statistic is the massive shortfall in ODA/GNI ratios relative to the agreed target of 0.7 per cent.

The OECD estimates that in 2014 the ratio for all nations “would be 0.29%”.

The following graphic from the OECD shows the state of its Member Nations in 2014 relative to the 0.7% target.

In 2013, Australia was estimated to be the fifth wealthiest of the 34 OECD countries in terms of wealth per adult (standardised in US dollars) behind Iceland, Switzerland, Norway and Denmark (Source).

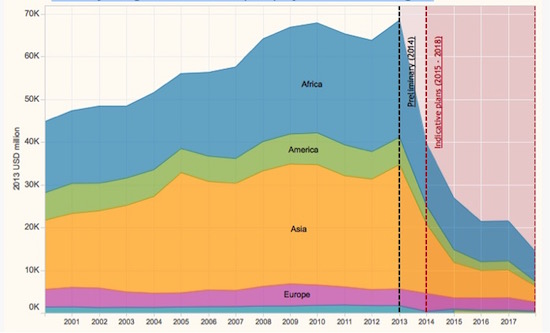

The OECD also conducts a – Survey on Donor’s Forward Spending Plans – which provides estimates of the – Country Programmable Aid (CPA) by Income and Region – likely to be provided by the participating DAC nations.

The data “only covers the aid providers that have agreed to publicly share the information”. Australia does not share its information.

CPA is “the portion of aid that providers can programme for individual countries or regions, and over which partner countries could have a significant say. Developed in 2007, CPA is a closer proxy of aid that goes to partner countries than the concept of Official Development Assistance (ODA)”

But the following graph shows the intentions for all the DAC nations who did share the data by region out to 2018 in real terms (2013 US dollar millions).

The outlook is very poor.

What aid that will be forthcoming will be less discretionary for the recipient nations.

Australian government announces major cuts to ODA

Australia’s performance in terms of ODA has been appalling given its high per capita incomes and wealth.

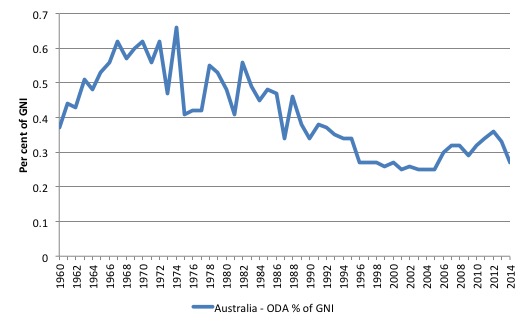

The following graph shows the OECD ODA/GNI ratio since 1960. In the 1960s, when Australia enjoyed true full employment (less than 2 per cent with zero underemployment), Australia was among the most generous providers of ODA to the poorer nations).

Our international aid assistance was very close to the 0.7 per cent of GNI range that was subsequently agreed to be the acceptable target for advanced nations.

The decline began in earnest in the early 1980s. You will no doubt realise that this decline coincided with the onset of neo-liberal macroeconomic thinking which attempted to construct the aid in terms of excessive spending and a denial of other prioritised spending.

This argument has especially been used during recessions where government start claiming that nations who are in recession no longer have the means to extend their generosity to the poorer nations.

The whole construction is, of course, deeply flawed.

A nation in recession that issues its own currency has no more or no less financial capacity available to provide ODA than a nation that is growing strongly.

In fact, it is in the interests of a nation in recession to not only introduce counter-cyclical domestic fiscal policy initiatives but also to increase ODA because the poorer countries tend to import from the more advanced. The more income that is produced in the poorer nations the more likely it will be that the exports of the advanced nation will hold up or increase.

So this false idea that a recession reduces capacity is endemic and damaging innocent people everywhere. A nation mired in recession has more real resources available than ever and is living well below its means rather than the way the fiscal austerity proponents like to say (living beyond their means).

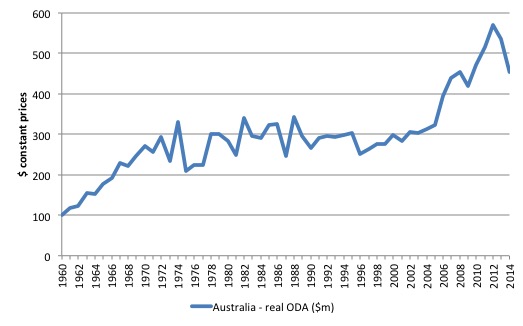

The following graph shows the history of Australian ODA from 1960 in constant dollar terms (deflated by the GDP Implicit Price Deflator).

After a period where there was no real growth in aid, in the few years before the GFC the Australian government increased its ODA outlays in real terms. But that increase in generosity has now reversed.

And things are going to get worse …

The previous Labor Government started the rot. I have written about this before in this blog from 2012 – Neo-liberals can’t even identify self-interest when it is staring at them.

In 2013, the UK Guardian wrote that:

Australia was once considered one of the world’s most generous aid donors. More recently, Canberra has been criticised for pushing back plans to increase aid spending and for diverting money from overseas development projects to help pay for controversial asylum-seeker schemes at homeand in Papua New Guinea (PNG).

The election of the conservative government in September 2013 has seen the situation deteriorate even further.

0…..

The – Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook – as the name suggests, provides revised estimates from the ‘May Budget’ process and any changes to economic policy that the Government feels are appropriate given any shifts in context (circumstances).

I wrote about the most recent MYEFO in December 2014 in this blog – Australia – fiscal policy outcomes signal a failed government.

In the December 2014 MYEFO (page 24-25), the Australian government announced that it would:

The Government will return the level of Official Development Assistance (ODA) spending in real terms to the levels that applied when ODA was last funded from budget surpluses rather than debt and then grow ODA in line with the Consumer Price Index. This will improve the budget position by $3.7 billion over the four years to 2017-18.

Later (page 164), it added “The savings from this measure will be redirected by the Government to repair the Budget and fund policy priorities”.

The revised changes announced to Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) were cuts of $A1 billion in 2015-16, $A1.35 billion in 2016-17 and $A1.377 billion in 2018-19 – a total of $A3.727 billion.

Are these cuts significant?

The real cuts in 2014 amounted to 15.5 per cent.

Using the actual Treasury data for financial years (rather than the calendar year OECD data), we can project the announced cuts in the MYEFO out through the forward estimates period (to 2018-19).

We assume the deflator will average the projected Consumer Price Inflation over the period and that the ODA outlays will follow the projections set out in the MYEFO.

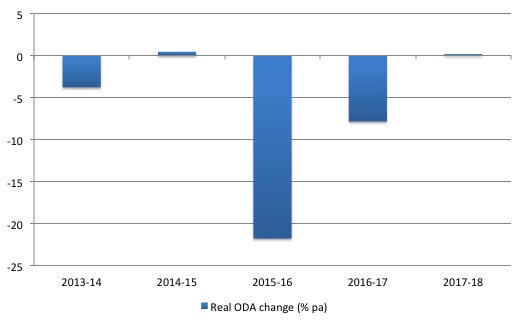

The following graph shows the percentage changes in real ODA outlays. The slight rise in 2014-15 is due to the slower than expected inflation as a result of the energy price declines. By 2017-18, the ODA is rising in line with inflation so the real growth is around zero.

The planned 22 per cent cut in real terms in 2015-16 would be one of the largest annual cuts in the history of the program.

In terms of the previous real peak in 2012-13 (the last year of the previous Labor government), the projected cuts by the conservatives will see ODA outlays decline by more than 30 per cent under current assumptions.

That is a dramatic shift in our behaviour towards the rest of the world.

And when you consider that the Australian government counts its spending on prisons in the Pacific to incarcerate refugee seekers as part of the ODA and this segment has been growing significantly in recent years, you get a good picture on why decent Australian people are starting to hang their heads in shame.

If we project out likely growth in GNI, we would find that by 2017-18 the ODA/GNI ratio would be at its lowest point ever – 0.22 per cent.

As a nation we are racing to the bottom of the OECD rankings and in violation of our international obligations.

We are also part of the advanced nation denial about terrorism and its link to poverty and poor education.

Conclusion

The Australian government should be increasing the fiscal deficit right now to ensure that domestic spending is sufficient to push unemployment down.

But it also should be increasing its ODA to ensure we meet our international obligations if achieving a ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7 per cent as soon as possible. After all we promised to achieve the latter goal in 1970!

Further, 22 of our nearest neighbours are considered to be developing nations. Why would we want to undercut the prospects of our nearest neighbours?

Even self-interest tells us that it is foolish to leave our trading partners poor.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

If only the average person on the street realised that a government repairing it’s balance sheet under the current circumstances is essentially destroying the balance sheets of the private domestic sector.

The attack on foreign aid is relentless. I can’t understand it given that it is essentially an export stimulus.

Ship weapons to foreign lands – no problem. Ship water pumps to foreign lands – must be stopped.

Is this what we have become?

1. At least I can be smug in that the UK government (so far) has ringfenced ODA at .7%. Being as (I assume) ODA is denominated in the donating country’s own fiat currency any amount is theoretically possible. It remains to be seen, of course, what happens after the election.

2. Could I suggest that the word “Groupthink” should be substituted for “Gobbledygook”? (I assume you have this word in Australia).

Neil, because it is exporting real goods and services out of the country to foreigners, people dislike it. It may be “export stimulus” but it is not seen that way by most people.

[Bill edited out link to a minor third-party sight that he does not wish to promote via billy blog traffic]

From Rogue Economist:

“With a JG, the first businesses to fall off when government starts dampening inflation are those that employ the most number of basic skill level employees, regardless of whether they took on more debt. Also, because a JG entails all private sector hiring start at wages above this level, JG’s highest effect will be among those whose skills end up matching the JG the most, drivers, couriers, dispatchers, seamen, waiters…I’m speculating we’ll see less shipping and logistics companies, and much higher prices charged by those fewer companies left standing. Imagine how much worse their cost structure gets when the government starts clamping down on inflation. Though government bureaucrats may be agnostic as to the fate of workers, not all businesses are created the same. There are those that will probably never get started in the private sector with a permanent JG in place.”

JG will require beuracracy and kill small businesses.

Bob:

So the answer is to throw the unemployed and underemployed under the bus to save the under paid jobs then?

No, JG is fine in deflationary/normal periods.

I think JG should a just for state of economy, so when the economy is bad JG high and when good low wage.

JG works fine for full employment but not as well for price stability. Correct me if I am wrong Bill.

There’s a 40 min podcast interview with Sarah Chayes here http://johnbatchelorshow.com/podcasts/mon-2915-hr-4-jbs-thieves-state-why-corruption-threatens-global-security-sarah-chayes

Bob:

The job guarantee would seem to be self adjusting wouldn’t it? Inflation shouldn’t (barring policy mistakes) become much of a factor until you get very close to full employment.

You are wrong, Bob. Inflation can be controlled with taxation instead of unemployment. And your previous comment assumes that people will en masse leave their existing jobs (along any benefits, promotion prospects, the social aspects and any pay rises they have earned) to be reliant on a minimum wage JG job?

Think, man, think. People don’t act according to any model. Especially economics modelling.

China is embarking on a massive development project throughout the developing World. I don’t know if they will be successful, but they are thinking big … US after WWII big. The best example is the high-speed train network they are proposing to cover the globe is the most prominent example. This is what the US once did … now we look for someone to bomb.

By the way, Greece could probably get substantial help from Russia and China if they decided to fling the EU to the wind (noted with some trepidation in neo-liberal circles).

“You are wrong, Bob. Inflation can be controlled with taxation instead of unemployment. ”

Not self correcting then. Yes, but in a boom I worry that high tax rates and labour costs will result in lack of enterprise.

How do you intend to control inflation in a boom with JG then without cutting the JG wage?

You are essentially forcing small businessmen onto the JG.

“And your previous comment assumes that people will en masse leave their existing jobs (along any benefits, promotion prospects, the social aspects and any pay rises they have earned) to be reliant on a minimum wage JG job?”

? I am wondering what will control inflation.

I support JG, I have some questions about it.

Easy, Bob. Tie the JG wage to housing costs instead of general price inflation (CPI).

This keeps wages in small businesses from rising too high because JG wage doesn’t increase based on the price increases coming from businesses (as housing costs are not tied to the cpi but other factors) and therefore is unlikely to cause spiralling wage/price inflation.

There are other policy tools that could be used in conjunction to keep the scales balanced in favour of true innovators (we could certainly start giving them taxation privilege preference over property investors, couldn’t we?).

Jeff, that is an even worse idea.

Ideally, we should be reducing housing “costs” by 100% Land Value Tax, to stop property “investors.”

I also thought the JG wage was fixed? Correct me if I am wrong.

Mind you, I guess this is unlikely to be an issue due to depressed demand at the moment.

I am sure there are easy ways to reduce inflation when that becomes a problem. Just run surpluses excluding the JG (full employment budget surplus.)

Bill, is the full employment budget even applicable when you have JG?

Far better to have the richer folk bear it than keep many unemployed.