In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Who are the British that are living within their means?

The British Prime Minister gave a New Year’s speech in Nottingham on Monday (January 12, 2015), where he railed about the “dangers of debts and deficits” as part of the buildup to this year’s national election in Britain. There does not appear to be an official transcript available yet so I am relying on Notes that the Government released to the press containing extracts (Source). However, it is clear that the framing used by the British Prime Minister was seeking to personalise (bring down to the household level) public fiscal aggregates and invoke fear among the ignorant. The classic approach. There was no economic credibility to the Prime Minister’s claims. But that doesn’t mean that it wasn’t a politically effective speech. So woeful was the response by the Opposition that it suggested Cameron’s speech was very effective. That is the state of things. Lies, myths and exaggeration wins elections.

The British Prime Minster said that overhanging the election was “The spectre of more debt” if the Opposition was elected.

He said that:

With the Conservatives, you get the opposite. A strong and competent team, a proven record, and a long-term economic plan that is turning our country around …

And then went on to claim that economic chaos would follow under Labour because debt would be higher, there would be “more spending … and higher taxes” and “higher interest rates too – punishing homeowners, hurting businesses, losing jobs.”

He claimed that “reducing the national debt is essential” but for moral as well as economic reasons:

It is about the values of this country, whether we as a nation are going to pass on a mountain of debt to the next generations that they could never hope to re-pay. To every mother, father, grandparent, uncle, aunt – I would ask this question. When you look at the children you love, do you want to land them with a legacy of huge debts?

Hmm, we have travelled this path before. The statements have no economic foundation – but are framed cleverly to appeal to the ignorance of the population and the well crafted fears about what a Labour government would do.

Of course, the Labour government is as neo-liberal as the Conservatives but that is a minor detail in the political struggle.

As this article – David Cameron and the national debt monster in three charts – in the populist UK Telegraph (January 12, 2015) notes:

It’s a sign of successful that attack has been that the respectable macroeconomic debate about whether deficit spending in an era of low growth and low interest rates is or is not a bad thing is almost wholly absent from British politics: for politicians and most voters, deficits are bad, debt is bad. End of story.

There is no economic foundation to Cameron’s claims.

There is no debt burden borne by the future generations. That is a total myth.

Please read my blog – Will we really pay higher taxes? and Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for an introduction to this issue.

The only reasonable conclusion when you understand how the monetary system functions is that burdens can only be considered in terms of real resources. In that context, the level of public debt that is carried through time has no bearing on what each generation is able to consume (or produce).

The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able.

Clearly, governments bent on fiscal austerity deliberately deny successive generations the ability to consume and produce but that is not an intrinsic function of the level of public debt outstanding.

It is rather a wrongful policy direction driven by an irrational fear (and ignorance) of what the public debt means.

The mainstream belief is based on the erroneous conflation of a household and government budget. So when a household/firm borrows now to increase current consumption (or build productive capacity) there is a clear understanding that future income will have to be sacrificed to repay the loan with interest.

This result follows because spending by the non-government body (household and/or firm) is financially constrained.

A household must finance its spending either by earning income, running down saving, borrowing and/or selling previously accumulated assets. There is no other way. Borrowing has to be repaid via access to the other sources of spending capacity but by implication such repayments reduce the future capacity to spend.

This is translated (erroneously) into the public sphere with the claim that governments have to pay the debt back in the future by increasing taxes.

The consumption benefits of the higher spending now are enjoyed by us and our children pay for our joy by facing higher tax burdens. That is the nub of the mainstream argument.

But do our children forego real consumption in this way? Answer: no!

If our children produce $x billion in real GDP in 2020 all of that flow of real goods and services (and income) will be available for consumption should they choose to do that. They probably will save some of it (especially if the government runs a deficit of sufficient magnitude to fill the spending gap left by the desire to save by the non-government sector).

But the important point is that real GDP is not a reverse-time traveller. There is no government agency collecting real output to “pay back past debts”.

Moreover, running fiscal deficits which support aggregate demand at levels where everybody who wants a job can get one maximises employment and output each year and provides each demographic with the best opportunities to expand their real consumption possibilities.

Fiscal austerity – in the misguided hope that the public debt ratio will fall – undermines growth over time and the resulting unemployment erodes the capacity of our children to consume in the future. Potential output (expanded by investment) and productivity growth are cyclical in the sense that if an economy is in recession or stagnating investment falters and future growth potential is reduced. Similarly, productivity growth lags when aggregate levels of activity falter.

So the best way to increase the opportunity set for our children is to keep (environmentally-sustainable) economic growth strong and fiscal austerity will typically work against that reality.

The public debt ratio has no bearing on any of this. The only possible burden on our children relates to my term “environmentally-sustainable” which includes consuming through time within the limits of real resource availability.

If the current generation undermines the world’s environment and exhausts finite resources then unless technology changes dramatically (for example, to use different energy sources for transport, etc) then our children will not enjoy the same lifestyle that we enjoy (using enjoy liberally!). But that conclusion relates to competing uses of real resources.

The public debt ratio has nothing much to do with that possibility.

Public policy should be aiming to promote material prosperity across time that allows the available real resources to be shared across generations and prorated according to a sense of public purpose. Using the “price system” only prorates according to “dollar votes” and intertemporal considerations are subjugated.

Once you understand that there are no real consumption burdens to be borne by our children as a result of the public debt ratios, you then can trace the origin of this myth to the false government/household analogy.

A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. A household is always financially constrained because it is the user of the currency.

This distinction means that the implications of a government budget is not even remotely like that of a household. When the government spends it credits bank accounts. The funds come from nowhere! When it taxes it debits bank accounts. The funds go nowhere!

Please read my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

These blogs tell you that government debt is just an interest-bearing manifestation of non-government saving and the funds “borrowed” by the government are just come from what it has spent anyway.

Governments pay back debt (upon maturity) and service the interest payments just like it spends more generally.

It moves funds from an account at the central bank to the commercial banking system. There is no “financing” constraint involved.

There are clearly distributional issues involved in issuing and servicing public debt. The poor typically do not have savings which are can be used to purchase the debt and hence do not enjoy the income flows arising from servicing the debt. While these issues are important and should be considered they have no bearing on the legitimacy of the “debt burden” argument.

That argument is plain wrong.

There is a case to be made that the government should stop issuing any debt when it net spends. Such an action is unnecessary in a fiat monetary system and the benefits of the debt issuance do flow to the top-end-of-town more often than not.

The other side of the equity argument however is that we should consider who benefits from the net public spending. Both considerations are important aspects of public policy. But the debate is never about the burdens of paying back the debt. There are no burdens.

Please see these blogs – Lower deficits now, undermine our grandchildren’s future – When 50 per cent youth unemployment is (apparently) protecting the grand kids – for further discussion.

Mainstream economists also claim that government spending crowds out private spending by pushing up interest rates. The story goes that governments have to borrow to fund their spending and that that borrowing is drawn from a finite pool of savings at any point in time.

As the pool diminishes, the cost of drawing on those savings rises – that is, the interest rate rises.

As a consequence, components of private spending that are sensitive to interest rate rises fall.

The alternative view, which reflects the way the system actually operates, is that a spending increase stimulates aggregate demand, which in turn, boosts output and incomes. The rising incomes generate higher savings.

Further, the capacity of households and firms to borrow from commercial banks is not constrained by the current reserves held by those banks.

In that sense, government borrowing does not limit the capacity of private sector borrowers to access funds at the current interest rates.

Moreover, the funds that the government borrows came from past government spending anyway.

The conceptual issues aside, the British Prime Minister’s speech also seemed to defy reality. It goes to show that if you say something enough times for long enough the facts become irrelevant and one can even defy one’s own logic (however flawed) and still advance one’s self interest.

At his Nottingham Speech, he addressed the audience in front of a backdrop which featured text about leadership and economic plans with the slogan “A Britain Living Within Its means” being prominent. Here is a snapshot of the background.

And closer up:

Despite the beautiful blue tones on display, I thought his framing was, in itself, fraudulent, although few would pick that up.

First, even within his own twisted neo-liberal logic, the British government has (thankfully) failed to meet is fiscal targets.

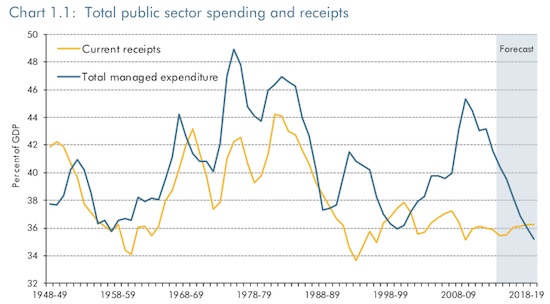

After they were elected in May 2010, the Conservatives delivered their – Autumn Statement 2010 on November 29, 2010, which outlined the fiscal strategy of the Government.

The Chancellor stated that:

… the most important point is this – the lesson of what is happening all around us in Europe is that unless we deal decisively with this record budget deficit then many thousands more jobs will be at risk – in both the private and the public sector … let me summarise the forecast for the public finances – which shows that Britain is decisively dealing with its debts.

They forecast that the public debt to GDP ratio would fall to 69 per cent in 2013-14 and then to 67 per cent by 2015-16.

They also said they would “eliminate the structural current budget deficit one year early, in 2014-15”.

Well, they didn’t do any of that and their ‘failure’ is one of the reasons the economy resumed growth with declining unemployment.

Had the Government actually succeeded in their ridiculous ambitions the recession would have continue unabated.

In the – Economic and fiscal outlook – December 2014 – the Office of Budget Responsibility estimated in the 2014 Autumn Statement (delivered in December 2014) that the public net debt to GDP ratio in 2013-14 will be around 79 per cent (December forecast) and will rise to 80.4 per cent in the current fiscal year (2014-15).

Then the OBR estimate that the public debt ratio will:

… rise as a share of GDP this year and next, peaking at 81.1 per cent of GDP in 2015-16, before then falling at an increasingly rapid rate to 72.8 per cent of GDP in 2019-20.

So ‘living within their means’? Not according to their own logic. But I am sure some of the unemployed that managed to get jobs are not going to complain about the ‘failure’.

Please read my blog – UK economy grows and so does its budget deficit and British economic growth shows that on-going deficits work– for more discussion on this point.

The increased borrowing ratio is because the fiscal deficit has not be cut as sharply as predicted. Since 2010-11, spending has risen by some £32 billion, while total central government revenue has risen by £61 billion meaning the fiscal deficit has fallen by only £29 billion. The increased tax revenue is mostly being driven by the growth that the continuing large deficits have been supporting.

And relative to the forecasts that the Government made at the outset, they have been (using their own terminology and framing) ‘binging on taxpayers funds’ and ‘mortgaging their grandchildrens’ futures’!!

The data shows that in the – Budget Forecast – June 2010 , the Government predicted that by 2014-15, the fiscal deficit would be £17 billion (2.3 per cent of GDP) and the PSNB (allowing for depreciation of capital items) would be £37 billion (3.5 per cent of GDP).

The December 2014 Economic and Fiscal Outlook tells us that the likely 2014-15 fiscal deficit will be of the order of £63.6 billion (3.5 per cent of GDP) and the PSNB would be £91.3 billion (5 per cent of GDP).

Again, ‘living within their means’? Not according to their own logic.

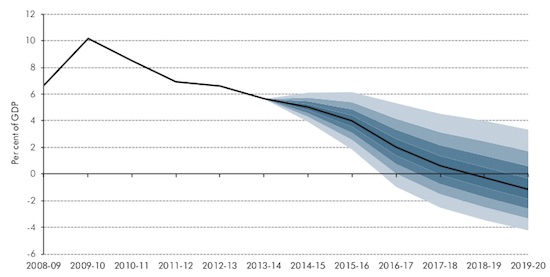

As an aside, Chart 4.10 in the Economic and Fiscal Outlook demonstrates how ridiculous it is trying to pin down fiscal targets when the final outcomes are dependent on the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector.

The so-called ‘PSNB fan chart’ (PSNB = Public Sector Net Borrowing or fiscal deficit plus any new debt) shows the dergree of confidence that the British Treasury has concerning their deficit forecasts shown in the graph as the thick black line surrounded by the blue shading. The thick black line up to 2013-14 (approximately) is the actual (known) PSNB and then the forecast period goes out to the 2019-20 financial year.

The blue shading “represent 20 per cent probability bands, based on the pattern of past official forecast errors”.

To understand how to interpret the chart, imagine that the economic situation (and all other forecasts) were to hold at the start of the forecast period for 100 separate occasions.

Then the forecasted PSNB would lie in the darkest band on 20 out of the 100 occasions. And as we move out to lighter shaded areas we would make similar statements for the implied PSNB number.

Overall, the OBR is telling us that by 2019-20, the fiscal balance (approximately) will lie somewhere between a surplus of just over 4 per cent of GDP or a deficit of around 3.8 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 80 times out of 100.

In other words, the accuracy of the projections is so low at the end of the forecast period to be meaningless, given that the two possible fiscal outcomes are so different in their implied impact on the economy and their implications for what non-government balances would be to support such outcomes.

The Government then proposes the following nonsensical fiscal cut back over the next five years. Obviously, some genius in the Treasury (or OBR) has been told that they have to get a surplus by 2018-19 and then drew the spending cut line to meet that objective.

If that net public spending contraction was to happen given the state of the external sector and the already heavily indebted private domestic sector, then pigs would be flying or the economy would be pushed back into deep recession.

The problem is that if they really try to cut spending by that much and that quickly then the recession will come before the pigs take-off.

Of course, the other side of the picture is what the non-government sector is up to. As I noted in my analysis of the Conservative’s first fiscal statement in June 2010,

In this blog – I don’t wanna know one thing about evil – written in April 2011, I provided detailed analysis of the official British Treasury documents from the UK Budget 2011.

As I noted then, there was a lot of reference to debt.

Under the heading “A strong and stable economy” (Page 7) you read:

… Over the pre-crisis decade, developments in the UK economy were driven by unsustainable levels of private sector debt and rising public sector debt. Indeed, it has been estimated that the UK became the most indebted country in the world … Households took on rising levels of mortgage debt to buy increasingly expensive housing, while by 2008 the debt of nonfinancial companies reached 110 per cent of GDP. Within the financial sector, the accumulation of debt was even greater. By 2007, the UK financial system had become the most highly leveraged of any major economy … This model of growth proved to be unsustainable …

This discussion is in the context of a vulnerable and unbalanced economy relying too much on private sector indebtedness for growth and being very sensitive to housing price movements.

I completely agreed that a growth strategy that relies on the private sector increasingly funding its consumption spending via credit is unsustainable. Eventually, the precariousness of the private balance sheets becomes the problem and households (and firms) then seek to reduce debt levels and that impacts negatively on aggregate demand (spending) which, in turn, stifles economic growth.

The GFC showed how stark those type of adjustments can be.

But that quote was the only reference to household debt (or private debt) in the 2011 UK fiscal documents.

There was a massive amount of hectoring about the evils of public debt and the need to reduce it liberally appearing throughout the documentation.

The stated aim was to stimulate growth while bringing down debt levels in the economy (private and public). An appreciation of macroeconomics told us at the time that the only way those goals could be achieved would be if the external sector provided the demand stimulus to the economy capable of (more than) offsetting the net saving desires of the private domestic sector and the fiscal drag coming from the public austerity program.

At the time, there were very optimistic forecasts provided in Annex C (Table C.1) for Household consumption and net exports over the period 2011 to 2015. The net export forecasts have clearly not been achieved.

But, even if the net exports had have come in at forecast, the real GDP growth forecast provided at the time would have requred the very strong forecasted recovery in household consumption at a time when unemployment was still very high and growth in Real household disposable income was forecast to be negative in 2011 and then sluggish in the following years of the forecast horizon out to 2015.

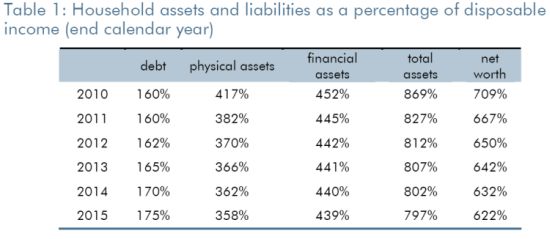

At the time, I did some digging to try to resolve this apparent contradiction. I discovered this document (published April 21, 2011) – Household debt in the Economic and fiscal outlook – which solved the puzzle but was deeply hidden in the fiscal documentation and barely referred to in any of the higher profile documents.

That document revealed the March 2011 household debt forecast that the OBR used as input for the “household debt projection in the Economic and fiscal outlook” (that is, the Fiscal Estimates):

Our March forecast shows household debt rising from £1.6 trillion in 2011 to £2.1 trillion in 2015, or from 160 per cent of disposable income to 175 per cent. Essentially, this reflects our expectation that household consumption and investment will rise more quickly than household disposable income over this period. We forecast that income growth will be constrained by a relatively weak wage response to higher-than-expected inflation. But we expect households to seek to protect their standard of living, relative to their earlier expectations, so that growth in household spending is not as weak as growth in household income. This requires households to borrow throughout the forecast period.

The following Table is taken from the OBRs Table 1 showed the forecasts for household assets and liabilities as a percentage of disposable income. The OBR says that “net worth is forecast to decline as a percentage of income as the household debt ratio is expected to rise and the household assets ratio is expected to fall”.

In other words, all the fuss about private and public debt levels and “dealing with our debts” in 2010 and 2011 was a smokescreen.

Its own growth strategy was always contingent on the private sector taking on a rising debt burden over the forecast period and becoming relatively poorer?

What the British government’s strategy amounted to was a deliberate plan to reduce public debt at the expense of more private debt.

Prudent fiscal management requires that exactly the opposite is the case when the economy is floundering – given current conventions about matching fiscal deficits with public debt issuance.

So which part of Britain is actually “living within its means”?

In July 2014, the Bank of England warned that the high household debt to income ratios in Britain remained a major risk to sustained recovery and financial stability

In a speech – guiding the economy towards a sustainable and safe recovery – the Deputy Governor noted that:

The rapid expansion of debt and accumulation of risks in the financial sector ended, as we all know, in a damaging and painful crash – for the financial sector and for the economy as a whole. There is a substantial body of international evidence that recessions are deeper and more painful when they follow a sharp run-up of debt and a banking bust. The UK recession in 2008-9 was a case in point …

At around 135% UK household indebtedness is high … But starting from this elevated level, the risk … is that with limited housing supply, the demand for housing in the UK continues to push prices up; that lenders are ever more willing to finance high loan-to-income mortgages as house prices rise, and that as a result household indebtedness climbs sharply, making the economy and financial system more vulnerable. This risk is greater at a time of exceptionally low interest rates which may well mask the likely true cost of a mortgage over time.

The latest data from the British Office of National Assessments (ONS) – United Kingdom Economic Accounts Time Series Dataset Q3 2014 – shows that while household debt to income ratios have fallen as a result of the crisis, they

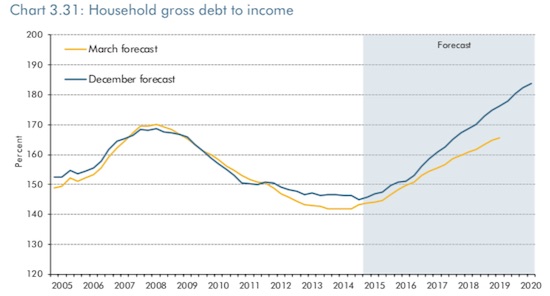

In the – Economic and Fiscal Outlook – December 2014 – the OBR publish one interesting graph (Chart 3.31), which shows the Household gross debt to income ratio fromm 2003 to 2020. I reproduce the graph below.

The OBR say that the ratio “has been revised up significantly since our March forecast” – by some £174 billion by 2019. They also acknowledge that there will be “a weaker forecast for wage growth” over the same period.

It is clear that British households are not forecast to be ‘living with their means’ anytime soon.

Conclusion

It is clear what ground the British election will be fought on in the coming months. Economic myths, data denials and lots of well-crafted myths about money, debt and deficits.

The real problem is that the British Opposition will go along with it and claim it will conduct austerity better and more fairly and all the rest of the nonsense. It might be time to close down any analysis of Britain for a while.

Further, please don’t take this “living within the means” stuff seriously when applied to the financial ratios of currency-issuing governments. When there is mass unemployment and underemployment then an economy has plenty of ‘means’ to bring back into productive use. Means mean real resources.

There is no sense that a currency-issuing government is ‘living within its means’ as measured by any fiscal outcome. The only sense that can be made of such a concept is to examine the state of productive resource utilisation. That, of course, was not what David Cameron was seeking to focus on.

Tomorrow, the first Australian labour market data for the year (actually for December 2014). We will see about that. I am not sure when the blog will come out as I have a long flight tomorrow which will take me to Sri Lanka! I hope to get it the labour market analysis done before I depart.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2015 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Apparently George Osborne has also added that Deflation may well happen in Britian but it won’t affect the economy. I think he may have had his fingers crossed at the time.

A brilliant analysis. Thank you.

All of that is true but I would opine that the real problem is one that is rarely talked about, which is ‘the ability to grow an economy in a global market’. In the UK the mantra is continually repeated that we had far worse indebtedness post WWII. That debt was very rapidly reduced (though not as rapidly in some other far worse war torn European economies).

Ignoring of course the post war economic circumstances in a society that aimed at full employment and a welfare system built around the notion of full employment. Such circumstances cannot be repeated in face of global economic competitiveness. And certainly not while maintaining the current welfare state, in the form of state subsidies (however they are presented).

We are a nation living beyond our means, presented with fiscal policies aimed at securing the votes of the sinecurist. This year’s general election in the UK is a poisoned chalice for whoever wins it. Austerity! Any fiscal spoonful of sugar won’t be seen by majority of the electorate, whoever they vote for.

Cameron, Harper and Abbott, all utterly incompetent yet crafty and devious. What have we done to deserve such trash?

Thats a great table (table 1- household debt) . Also, in 2011, Vince Cable (lib dem) was on show a few times, including on radio 4 I remember, admitting to the fact that household debt would rise and this was expected and part of coalition plans.

Unfortunately I have never heard him questioned about this by any opposition member, and more dissapointingly in the election run up, the greens (who we vaguely hope could provide some form of social libertarianism over here) fail to bring up anything to question neo-liberalism and in fact all signs currently point to them following the fiscal constipation advocated by the mainstream. TINA?!!?

If anyone in the UK is interested have a look on fb at UK transhumanist party. (and Bill of course you would be welcome to contribute there!) Most members are progressive and I think would place in the generally social libertarian political quadrant. Obviously there is more of a futurist bent than some of you may be used to.

Dear Bill

Let me make 2 comments.

1 – Britain is a country that continually runs current account deficits. It is therefore not living within its means.

2 – The claim that debt cannot burden posterity is valid only for a closed economy. If the country as a whole is going into debt, whether this is caused by the government or the private sector, then it is true that current generations in that country can live above their means while forcing future generations to live below their means.

Regards. James

John Doyle, I doubt if you personally have done anything to deserve the trash governments in the UK,Canada, Australia and the rest.

I know I certainly haven’t,apart from just existing.

But the majority of the electorate in these nations are appallingly ignorant about important issues re the economy and the environment. Whats more,they couldn’t give a stuff.

Just what the solution is to ignorance and stupidity I don’t know. Possibly a full on collapse with associated suffering.

“The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able.”

The UK more then any other country does not consume the outputs of its labour.

It consumes the products of global capital.

I guess they must seek to preserve capitalistic myths so as to remain at the centre of the global usury experiment as without this the UK is as poor as a church mouse..

The UK energy balance tells you all you need to know about who consumes in that land.

We are witnessing crashing coal , gas, heavy fuel oil and electricity consumption which the poorer classes once consumed on a large scale while transport fuel inputs such as diesel continue to rise as people travel to non productive jobs so as to access purchasing.

power.

PS

There is no real energy replacement for oil in the transport sector.

At best you can create a critical mass orbiting a railway station hub which will reduce real inputs.

Only productive transport investments the UK can make is a reinstallation of rural branch lines destroyed during the beeching cut era.

@Hugh of the North

“the greens (who we vaguely hope could provide some form of social libertarianism over here) fail to bring up anything to question neo-liberalism and in fact all signs currently point to them following the fiscal constipation advocated by the mainstream”

I recently joined the Green Party in that same vague hope and so far, (in the limited time I’ve spent among my local party) the term “neoliberal” has been used a fair bit, in the sense of “us versus the 4 neoliberal parties”, which gives me some hope they’re on the right track. There’s certainly contempt for austerity.

However, I haven’t yet got a full understanding of what they mean by their “not being neoliberal” – fingers crossed their economic policy people are all over MMT. They should be!

Prof. Mitchell may well be right that politicians and mainstream economists exaggerate the burden of debt on future generations. But unfortunately the analysis here is over-simplified and counter-intuitive.

The analysis here is only good for a closed economy.

It is seriously flawed for an open economy.

About 30% of UK national debt is owned by foreigners, over 400 billion pounds, roughly 5,000 pounds per head of population or 23% GDP.

See UK Debt Management Office publications:

http://www.dmo.gov.uk/index.aspx?page=publications/quarterly_reviews

So Prof. Mitchell could be seriously mistaken in stating that “The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able.” This statement assumes that future generations will always be able to borrow again from foreigners to make interest and redemption payments to foreigners. Otherwise the welfare of future UK generations will be reduced.

Alternatively the UK could default on its debts, but this is likely to have an even worse adverse effect on the welfare of UK citizens.

@Andi

However, I haven’t yet got a full understanding of what they mean by their “not being neoliberal”

I’d suggest not joining parties before reading their manifesto.

http://greenparty.org.uk/assets/files/European%20Manifesto%202014.pdf

their economic understanding is a bit vague though,

quick search for words such as “deficit” yields:

“Germany’s trade surplus and Greece’s trade deficit are not unrelated.” ok,

searching for “tax” yields:

“EU governments lose a trillion Euros a year to tax dodging”, and Green MEPs will argue for mandatory VAT to be scrapped, for governments to be allowed to determine how they raise this share of their contribution to EU budgets. might be an indication of their lack of understanding, however the phase out of VAT altogether seems interesting.

I’d argue for VAT to control the velocity of money going towards essential goods vs non essential goods where the production process is competing for resources. The effectiveness of a tax at keeping prices stable is not related to it’s nominal return. The amount of high powered money you can take out of the economy is minimal.

Hello,

“The latest data from the British Office of National Assessments (ONS) – United Kingdom Economic Accounts Time Series Dataset Q3 2014 – shows that while household debt to income ratios have fallen as a result of the crisis, they ”

Something left out?

James Schipper,

Lets take a look at what you are arguing:

1) “Britain is a country that continually runs current account deficits. It is therefore not living within its means.”

You are making the point that Britain imports more stuff than it exports. About 5% of GDP. You don’t have to be an economist to know that trade, worldwide, has to balance. So, for every deficit, there has to be a surplus. If every country exactly balanced its trade, which is arithmetically possible, would that mean that every country was living exactly according to its means? Not a penny more, not a penny less? It would – according to your view. This would apply equally to any every country regardless of whether they had 25% unemployment or full employment.

Is this really a sensible way of looking at it?

2) “…. then it is true that current generations in that country can live above their means while forcing future generations to live below their means.”

What’s the worst that can happen? The countries that have accumulated claims on the UK economy by being net exporters (like Switzerland, China, Germany etc) might suddenly wish to implement these claims by becoming net importers. That seems unlikely, but it is possible I must admit. They may wish to start buying lots of jet engines from Rolls Royce. Or may suddenly develop a taste for Scotch whisky and might start ordering lots of the stuff. To preserve the value of their unclaimed assets it’s unlikely Britain’s ‘creditors’ would want to go overboard in that. It is very unlikely they’ll order so many engines from Rolls Royce that the UK economy would be unable to cope. But if that were to happen the UK simply could apply an export tax.

So a more realistic ‘worst case scenario’ , if you can call it that, would be that future UK generations would run an economy with a 5% surplus rather than a 5% deficit. I’ll believe that when I see it! But would it be such a bad thing?

@Andi

They arent! Sadly! as far as i can see anyway. I can probably find a few links regarding such.

anyway send me an email if you like and we can form an alliance against forces of economic evil. hughmac54@gmail.com

Dear KingKong (at 2015/01/14 at 22:14)

The UK gilts held by foreigners are in sterling. The “5000 pounds per head of population” is an irrelevant calculation. I owe none of the Australian government debt held by foreigners. And the UK government will always be able to service the gilts held by anyone. If the foreign holders choose not to purchase any more gilts then it will not undermine the UK government’s capacity to spend given its currency-issuing status. It might need to alter a few regulations and procedures.

It is possible that the exchange rate would make imports more expensive over time which reduces the real income of the nation at a given level of imports. But that doesn’t negate the statement that “The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able”. It just might alter the mix of traded and non-traded goods in the consumption package. It would also change the incentives of the nation to trade some of its current output.

The analysis holds for any degree of openness. There are special cases where a nation has no capacity to feed, heat or house itself without imports. Then it must export and may not be able to. But that is hardly the case of Britain or most other advanced nations.

best wishes

bill

Petermartin

It may have escaped your attention but the euro vassal countries which have experienced the biggest drive toward enforced current account surpluses be it Spain , Ireland or Greece have either historically close colonial ties with the UK or the subject of its military or intelligence aggression.

Greece being a perfect example given what happened in that country near the end of the war,

Hint….plucky spitfires were not used to shoot down 109s.

The British have a certain talent for creating facts on the ground and then later stating people were victims of random acts of the economic gods.

@Andi and other commentators on ‘Greens’

The UK green party appear to be fully signed up to Positive Money.

I find it ironic that they bang on about localism and the devolution of power and resources but they want to money creation to be (attempted to be) controlled by an unelected central authority! (as opposed to a network of local outlets able to assess local demand)

Pity, because they probably have more progressive policies in other areas than the rest of the parties put together.

The capitalist centre of Europe is a triangle with the three points being London , Paris & Amsterdam

The function of capitalism is not to produce goods for market but is simply a method of concentration using usury , subterfuge and military force if needs be.

Bill completely ignores the history of Britain as the British state was forming.

In particular during Tudor times.

The objective was to turn Ireland into a ranch as energy ( then food for men and horses) was concentrated.

Today in almost all euro crisis countries huge trade surpluses are forming with respect to deficit england,.

The true goal of the Russian crisis was to redirect agri and other products from chiefly France and Spain into the British black hole by simply reducing the size of the European scarcity engine,

In many cases the last market for these goods is deficit England and its growing population of urbanites.

This tactic is the oldest trick in the book.

Jesus Dork. A quote from Wikipedia or the like does not contribute to the discussion, especially the one you have included. What the hell are you doing?

petermartin2001: So a more realistic ‘worst case scenario’ , if you can call it that, would be that future UK generations would run an economy with a 5% surplus rather than a 5% deficit. I’ll believe that when I see it! But would it be such a bad thing?

I don’t know how many times I have explained this. Obviously the Chinese, Germans, Japanese think its wonderful to run a surplus. For a developing country it is great market discipline to be able to sell into a competitive market like the US. Other than that there probably isn’t much use … but it obviously hasn’t destroyed them.

Bill: you will especially enjoy this:

Britain can become world’s richest major economy, says George Osborne

Chancellor was speaking as he set out plans for new fiscal rule requiring government to operate budget surplus in normal times

http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/jan/14/britain-richest-country-world-george-osborne-fiscal-policy

John Doyle and Podargus,

The history of humanity has been a story of the control and manipulation of the gullible and stupid by the clever, devious and unscrupulous. It was ever thus. A full system breakdown would sow the seeds for revolution and change from the bottom up, hopefully for the better – however the history of previous revolutions doesn’t look to rosy in that regard, all too often they produced further tyranny and suffering. Regrettably, that seems to present the only possibility for effecting real change, away from the present destructive course of capitalism.

Dear petermartin

We really are on the same page. If a country can run current account deficits year after year after year without ever having to run current account surpluses, then it has in fact received a subsidy from foreigners. Lucky bastards.

In my view, there is no more foolish policy that running large trade surpluses. It can be counteracted by discouraging capital outflows, promoting greater economic equality or encouraging wages to rise.

If Britain will run trade surpluses in the future, it won’t necessarily come about through greater demand for British products abroad but could also be the result of reduced imports.

Regards. James

Hi again

The current account doesn’t consist only of trade. It also contains investment income and remittances. It is possible for a country to have a current account deficit but a trade surplus, or also to have a current account surplus but a trade deficit, as Britain had before WWI. Britain had been investing abroad for so long that its investment income was so high that it could run a trade deficit and still add to its foreign investments.

Let’s illustrate this. Ruritania has a current account deficit of 25 billion in perpetuity. The return on investment by foreigners in Ruritania is 4%, all of which is repatriated every year. We have then the following:

Year..current account..investment income..export- imports

1…….-25 billion……………00………………..-25 billion

2…….-25 billion………..-1billion…………….-24 billion

3……..-25 billion………..-2 billion……………-23 billion

11……-25 billion………..-10 billion………….-15 billion

26……- 25 billion……….- 25 billion………….00000

30……-25 billion………..-29 billion…………..4 billion

35……-25 billion………..-34 billion…………..9billion

51……- 25 billion……….-50 billion…………..25 billion

@ bill

Thanks for your response (January 15, 2015 at 5:59).

Unfortunately, the points you make don’t support your claim that “The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able”.

Yes, gilts are held in Sterling. Yes, the UK government will always be able to service the gilts held by anyone and to spend.

Even so, debt interest and redemptions paid to foreigners in the future will give foreigners the power to purchase UK goods and services. This means less future resources available for the UK government and/or UK citizens (at a given level of UK GDP).

I have no idea what you mean by altering “a few regulations and procedures”. How could these offset the resources taken by foreigners?

You recognise that “the exchange rate would make imports more expensive”. Yes indeed. If foreigners receiving interest or redemption payments don’t purchase UK goods themselves, they will sell their sterling for other currencies leading to devaluation, more exports, less imports, reduced consumption by UK citizens.

The analysis in your blog is a special case. It assumes that future generations will always be able to borrow again from foreigners to make interest and redemption payments to foreigners.

Is this is a reasonable assumption?

Or is there a danger that at some stage in the future foreigners could become unwilling to reinvest in sterling gilts because of low interest rates or risks of capital loss from holding sterling bonds due to the danger of further declines in value of sterling.

@KongKing,

I’m not sure if this is what Bill is hinting at but in theory the Government could create an Autarky! Nothing comes in nothing goes out! The statement “The next generation will be able to consume the outputs of their labour in the same way that the current generation is potentially able” then becomes literally true.

But say, in the future economy, there is 5% (in value terms) more stuff going out than coming in, and the government wants to equalise imports and exports. It needs to make exports dearer and imports cheaper. So why not a tax on exports used to subsidise the cost of imports?

@ petermartin2001

Autarky !

Is this Bill’s imaginary world? So unrealistic – no more imports! What a terrible prospect for UK consumers.

Export tax plus import subsidy !

With a floating exchange rate wouldn’t these just lead to inflation and an even bigger devaluation? There would still be a reduction in real spending and welfare for UK citizens.

Hopefully MMT will be generalised to include the constraints on policy options in an open economy.

Personally I like the simplifying assumption that future generations will always be able to borrow again from foreigners to make interest and redemption payments to foreigners.

However, this requires that the UK pays competitive interest rates and has a fairly stable currency.

KongKing,

I think you’re missing the point of MMT if you think there’s any need for countries to “pay competitive interest rates”. That’s just a way of increasing the value of the currency, over its natural level, which leads to the value of imports exceeding the value of exports. Basic arithmetic dictates that not all countries can be net importers. But, if all countries preferred to be net importers there would be a silly competition between countries to outsell treasury bonds. It’s only because most countries seem to take the philanthropic view that’s better to give than receive, ie assume the role of a net exporters that it makes sense for countries like the UK and the USA to let them. That means there is no need to pay any more interest than the rate of inflation.

There would be some strategic considerations if any country were to become too dependent on imports but we have to remember that the UK only rarely has a trade deficit approaching 5%. There’s really no need to worry about that.

You ask “Is this is a reasonable assumption?” about the need to continue the overseas sales of treasury gilts. I don’t think it is. Governments could impose direct trade controls if they wished. Closing down international trade is just an extreme example to show it is theoretically possible to do just that. Whether a negative tariff would work is debatable. It’s probably a bad idea all the same. It’s much better to let the trade balance to swing slightly into surplus if that’s the direction that economic forces are dictating. Again we’d be talking about just a few % of GDP. That’s really neither here nor there in comparison to the kind of economic problems, largely caused by economic incompetence, that Bill regularly writes about.

@Hamstray

I’d suggest not joining parties before reading their manifesto.

So would I! I did read their manifesto, however it doesn’t go into the level of detail required to get a full understanding of their understanding of economics. That’s ok, given their minimal media coverage the only way I’m likely to find out if they know what they’re talking about is to talk to them. If I don’t like what I find my membership isn’t permanent.

@Danny A

The UK green party appear to be fully signed up to Positive Money. I find it ironic that they bang on about localism and the devolution of power and resources but they want to money creation to be (attempted to be) controlled by an unelected central authority! (as opposed to a network of local outlets able to assess local demand)

Must confess I’ve seen Positive Money referred to on a few blogs but yet to get to grips with what it is. Haven’t heard the Greens mention it yet. A rundown by Bill would of course be wonderful, but it seems there are a number of Positive Money vs MMT blogs out there for me to read. Any recommendations would be useful.

@Hugh

The way I see it, I’m never going to find a party I agree with 100% (unless I start one and don’t let anybody join). The Greens are the closest I’ve found in a long while and although I nitpick with a number of their policies, they’ve got momentum right now and a progressive party on a roll is a rare thing in the UK. Felt it was important to back them as the only biggish party to oppose austerity and business as usual neoliberalism. They’re about to pass UKIP & the Lib Dems for membership and if they can harness the youth, most disadvantaged by the status quo, we might see some real change in the terms of debate. They may not have completely grasped MMT yet but given the membership surge perhaps a new wave of MMTers could influence policy! We live in hope.

Hi Andi

I am a branch coordinator and a parliamentary candidate for the GP. There are a few MMTers including myself amongst the ranks and yes we are trying to influence policy (I am hopefully going to organise a fringe event at the September conference). Unfortunately the Positive Money proposals got through on a “bash the banks” ticket so don’t be too hard on them for that. It is in our policies for at least another year due to not being able to change policies for 2 years once voted through. It is no means settled and if you go onto the members forum you will see the argument still raging as it is against a core principal as Danny points out above. PM are very good lobbyists and sold it to people as a “democratic committee” without really going into details.

HTH a bit.

@larry

it was not wiki …..I happen to know the area.

The place is wrecked now but it was not always the case.

All history is local and can be understood by looking at the history of a area town by town and even field by little field.

Dingle has always had a distant non Tudor / non Victorian feel about it until it was finally totally destroyed by euro credit inflation policies.

For most purposes now it no longer exists and must be avoided as is the case for almost all British towns in Gaelic lands which project strange and sickly artificial quality about them.

Fort William being a prime example of this effect.

Just to add a one Charles j haughey made some sort of political connection to this area.

The choice was not accidental.

From a British perspective he was not a proper little leader given his populist although highly corrupt dealings.

Strangely a new state pravda historical programme is showing him in a extremely positive light although with absurd Hollywood like undertones.

This is one for the books given Dublin 4s rejection of all things populist. so as to court their masters across the water.

His political career shadows the trajectory of the late 20th century Irish state from him back dating the widows pension in the late 6os to him engaging in classic neo liberal programmes post 86.

Of course he more then any other man s eeded local Irish control post 87.

@ Andi

Perhaps the best critique of +ve Money I have read (from a MMT perspective) is by Neil Wilson here:

http://www.3spoken.co.uk/2014/11/the-sovereign-money-illusion.html

(Sovereign Money ≡ Positive Money)

@ petermartin2001

There is no dispute here that full employment is the number 1 priority. I guess we agree that fiscal policy is the primary instrument for achieving this.

With GDP managed as closely as possible at the full employment level, borrowing from foreigners today would permit a current account deficit and higher spending today by UK consumers, firms and/or government.

Would there have to be a corresponding reduction in UK welfare in the future?

You mention the possibilities of autarchy, draconian government controls or default. However, the standard of living in the UK would slump without international trade.

More seriously you mention that the future trade balance could “swing slightly into surplus”.

Halleluyah, we agree !!

The surplus would be used to pay foreigners the interest and redemptions for past borrowings.

Achieving the surplus would require devaluation (or measures with a similar effect). And it would entail a REDUCTION in spending by UK consumers, firms and/or government.

The possible future burden should neither be under nor over-stated. Overseas holdings of UK national debt amount to about 23% GDP. Full repayment spread over a decade would therefore require cutting domestic consumption by more than 2% GDP (in order to permit the extra demand for exports and import substitutes resulting from devaluation).

@ KIngKong,

But is this likely? We’ve just seen Switzerland revalue the SF after years of running up big export surpluses. 16% of GDP the last time I looked. What was the point of that? They have built up huge reserves of Euros, Dollars and Pounds which they can’t spend unless they decide to become a net importer.

That’s not likely to happen any time soon. Probably not in our lifetimes. If there’s no reason to worry that our creditors might start spending our existing liabilities then there is really no reason to worry about giving them a few more.

PS I didn’t use the terms “draconian government controls” or “default”. You must be confusing me with someone else!

It does not seem likely at the moment that the case for continuing to run

government sector deficits is gaining traction in the uk.I think this blog

does give the best argument for persuading people otherwise.It is worth

stressing the private sector surplus argument every time you mention

government sector deficits .In the context of the uk and other nations in

external deficit it is always worth labouring the point that a balanced government

budget inevitably means an aggregate private sector deficit for such nations.

However I do share others concern with advocating a policy of running relatively

large external deficits on a permanent basis.For me this is not primarily for the

reasons given above although there have been many good points given regarding

assuming that foreign investors will always desire to hold savings in net importing

countries currency and what it would mean for the living standards of current net importing

countries if that assumption proves to be wrong.

For me the most important reason to avoid long term trade deficits is essentially

you are entering into a parasitical alliance with the international elite to

exploit the labour of working people in poorer nations.The external deficit representing

consuming resources you have not provided similar to parasitical financiers not

contributing real stuff but consuming it anyway.

What’s good for the goose is good for the gander

Dear KongKing

The foreigner income recipients of the bond-holding income have two options. They can first, leave the income in the local banking system, which may give them the capacity to purchase locally-produced goods and services. But what are they actually going to purchase? They are hardly going to purchase consumption goods.

They might buy real estate or other investment items, but then the government can easily set up foreign investment rules. For example, the Australian government has rules as to what foreigners can buy and under what circumstances. The limitations make them definitely not on an equal footing to locals in this respect. A sovereign government could stop foreigners buying any investment goods if it wanted to.

The second option is that they take the income out of the local banking system by selling it in the foreign exchange market. That would initially lead to some extra supply of the currency into the forex markets and might push the value down a bit but probably not much.

In that sense, exports might increase and so the local residents would be giving up some real resources to foreigners. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) explicitly acknowledges that exports are thus a cost. But that is not a problem that is confined to income earned from government bond holdings. Further, if the foreign income earners purchase export goods and services with their income that would push the exchange rate up and enhance the terms of trade in favour of the local residents.

Further, if the scale of the interest payments were causing a problem for local residents the central bank can control the yields (push them down) to a point where they do not cause a problem. People are now paying the German government for the perceived benefits they see in holding German bonds at certain maturities.

You are focusing on a non-problem. Ultimately, the government can stop issuing debt altogether, which is the preferred MMT option.

best wishes

bill

I don’t mind being left a mountain of “debt” but I do want good infrastructure and a healthy environment, low household debt due to a private sector surplus, not a bunch of worthless IOUs that I can’t spend.