Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – October 4, 2014 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) teaches us that a sovereign government does not have to issue debt to finance its spending. But the more public debt it voluntarily issues:

(a) the less is the volume of investment funds in the non-government sector that can be used for other investments.

(b) the greater is non-government wealth held in the form of public debt.

(c) the more difficult it is for banks to attract deposits to initiate loans from.

The answer is the greater is non-government wealth held in the form of public debt..

The option “the less is the volume of investment funds in the non-government sector that can be used for other investments”. You may have been tempted to select this option given that the government is withdrawing bank reserves from the system. So a bond issue is a financial asset portfolio swap.

However, banks do not need deposits and reserves before they can lend. Mainstream macroeconomics wrongly asserts that banks only lend if they have prior reserves. The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But this is not how banks operate. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves. As a result, investors can always borrow if they are credit-worthy.

Further, the option “the more difficult it is for banks to attract deposits to initiate loans from” also reflects the erroneous view of the banking system.

The correct answer is based on the fact that the when the government swaps bonds for reserves (which it has itself created via its spending) it is providing the non-government sector with an interest-bearing, risk free asset (for a sovereign government) in return for a non-interest bearing reserve. Reserves may earn a return but typically have not.

The bonds are thus part of the non-government sector’s stock of wealth and the interest payments comprising a flow of income for the non-government sector. So all those national debt clocks are really just indicators of public debt wealth held by the non-government sector.

I realise some people will say that the stylisation of government funds being provided by MMT doesn’t match the institutional reality where governments is seen to borrow first and spend second. But these institutional arrangements – the democratic repression – only obscure the essence of a fiat currency system and are largely irrelevant.

If they ever created a constraint that the government didn’t wish to accept then you would see institutional change being implemented very quickly. The reality is that it is a wash – net government spending is matched by bond issuance – irrespective of these institutional procedures and the government never “needs” these funds to spend.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Will we really pay higher interest rates?

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Hyperdeflation, followed by rampant inflation

Question 3:

A fiscal surplus indicates that the national government is

(a) trying to slow the economy down to contain inflation.

(b) trying to reduce public debt.

(c) you cannot conclude anything about the government’s policy intentions.

The answer is that you cannot conclude anything about the government’s policy intentions.

The actual fiscal balance outcome that is reported in the press and by Treasury departments is not a pure measure of the fiscal policy stance adopted by the government at any point in time. As a result, a straightforward interpretation of the government’s discretionary fiscal intentions is not possible when using the actual reported fiscal outcome.

Economists conceptualise the actual fiscal outcome as being the sum of two components: (a) a discretionary component – that is, the actual fiscal stance intended by the government; and (b) a cyclical component reflecting the sensitivity of certain fiscal items (tax revenue based on activity and welfare payments to name the most sensitive) to changes in the level of activity.

The former component is now called the “structural deficit” (or surplus) and the latter component is sometimes referred to as the automatic stabilisers.

The structural deficit/surplus thus conceptually reflects the chosen (discretionary) fiscal stance of the government independent of cyclical factors.

The cyclical factors refer to the automatic stabilisers which operate in a counter-cyclical fashion. When economic growth is strong, tax revenue improves given it is typically tied to income generation in some way. Further, most governments provide transfer payment relief to workers (unemployment benefits) and this decreases during growth.

In times of economic decline, the automatic stabilisers work in the opposite direction and push the fiscal balance towards deficit, into deficit, or into a larger deficit. These automatic movements in aggregate demand play an important counter-cyclical attenuating role. So when GDP is declining due to falling aggregate demand, the automatic stabilisers work to add demand (falling taxes and rising welfare payments). When GDP growth is rising, the automatic stabilisers start to pull demand back as the economy adjusts (rising taxes and falling welfare payments).

The alternative is true when the economy is growing fast – tax revenue increases and welfare payments decline. So a fiscal balance may move into surplus even though the discretionary policy stance is expansionary. This would mean however that the overall fiscal impact is contractionary because the automatic stabiliser impact is overriding the discretionary intent.

The problem is always how to determine whether the chosen discretionary fiscal stance is adding to demand (expansionary) or reducing demand (contractionary). It is a problem because a government could be run a contractionary policy by choice but the automatic stabilisers are so strong that the fiscal balance goes into deficit which might lead people to think the “government” is expanding the economy.

So just because the fiscal balance goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this ambiguity, economists decided to measure the automatic stabiliser impact against some benchmark or “full capacity” or potential level of output, so that we can decompose the fiscal balance into that component which is due to specific discretionary fiscal policy choices made by the government and that which arises because the cycle takes the economy away from the potential level of output.

As a result, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. As I have noted in previous blogs, the change in nomenclature here is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construction of the fiscal balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the fiscal position (and the underlying fiscal parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

This framework allowed economists to decompose the actual fiscal balance into (in modern terminology) the structural (discretionary) and cyclical fiscal balances with these unseen fiscal components being adjusted to what they would be at the potential or full capacity level of output.

The difference between the actual fiscal outcome and the structural component is then considered to be the cyclical fiscal outcome and it arises because the economy is deviating from its potential.

So if the economy is operating below capacity then tax revenue would be below its potential level and welfare spending would be above. In other words, the fiscal balance would be smaller at potential output relative to its current value if the economy was operating below full capacity. The adjustments would work in reverse should the economy be operating above full capacity.

If the fiscal balance is in deficit when computed at the “full employment” or potential output level, then we call this a structural deficit and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is expansionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently. If it is in surplus, then we have a structural surplus and it means that the overall impact of discretionary fiscal policy is contractionary irrespective of what the actual fiscal outcome is presently.

So you could have a downturn which drives the fiscal balance into a deficit but the underlying structural position could be contractionary (that is, a surplus). And vice versa.

The question then relates to how the “potential” or benchmark level of output is to be measured. The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry among the profession raising lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s.

As the neo-liberal resurgence gained traction in the 1970s and beyond and governments abandoned their commitment to full employment , the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

The estimated NAIRU (it is not observed) became the standard measure of full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then mainstream economists concluded that the economy is at full capacity. Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

Typically, the NAIRU estimates are much higher than any acceptable level of full employment and therefore full capacity. The change of the the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance was to avoid the connotations of the past where full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels.

Now you will only read about structural balances which are benchmarked using the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending because typically the estimated NAIRU always exceeds a reasonable (non-neo-liberal) definition of full employment.

So the estimates of structural deficits or surpluses provided by all the international agencies and treasuries etc all conclude that the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is – that is, bias the representation of fiscal expansion upwards.

As a result, they systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

The only qualification is if the NAIRU measurement actually represented full employment. Then this source of bias would disappear.

Why all this matters is because, as an example, the Australian government thinks we are close to full employment now (according to Treasury NAIRU estimates) when there is 5.2 per cent unemployment and 7.5 per cent underemployment (and about 1.5 per cent of hidden unemployment). As a result of them thinking this, they consider the structural deficit estimates are indicating too much fiscal expansion is still in the system and so they are cutting back.

Whereas, if we computed the correct structural balance it is likely that the Federal fiscal deficit even though it expanded in both discretionary and cyclical terms during the crisis is still too contractionary.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- A modern monetary theory lullaby

- Saturday Quiz – April 24, 2010 – answers and discussion

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

- Another economics department to close

Question 3:

A currency-issuing government can run a balanced fiscal balance over the business cycle (peak to peak) as long as it accepts that after all the spending adjustments are exhausted that the private domestic balance will only be in surplus if the external balance is in surplus.

The answer is True.

Note that this question begs the question as to how the economy might get into this situation that I have described using the sectoral balances framework. But whatever behavioural forces were at play, the sectoral balances all have to sum to zero. Once you understand that, then deduction leads to the correct answer.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

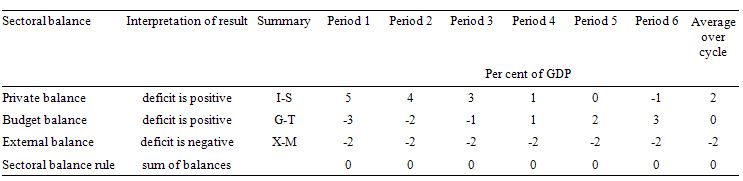

To help us answer the specific question posed, the following Table shows a stylised business cycle with some simplifications. The economy is running a surplus in the first three periods (but declining) and then increasing deficits. Over the entire cycle the balanced fiscal rule would be achieved as the fiscal balances average to zero. So the deficits are covered by fully offsetting surpluses over the cycle.

The simplification is the constant external deficit (that is, no cyclical sensitivity) of 2 per cent of GDP over the entire cycle. You can then see what the private domestic balance is doing clearly. When the fiscal balance is in surplus, the private balance is in deficit. The larger the fiscal surplus the larger the private deficit for a given external deficit.

As the fiscal balance moves into deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance and then finally in Period 6, the fiscal deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) and so the private domestic sector can save overall. The fiscal deficits are underpinning spending and allowing income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector.

On average over the cycle, under these conditions (balanced public fiscal balance) the private domestic deficit exactly equals the external deficit. As a result over the course of the business cycle, the private domestic sector becomes increasingly indebted.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

re 1) So when a currency issuing government issues debt for erroneous financing purposes, they are also unnecessarily building into future budgets costs in the form of interest payments for the debt issued.

The public debt is also basically just for the Banks, I don’t know any individuals who own Govt bonds. It’s a subsidy for the wealthiest sector.

Banks’ lending is Capital constrained, banks have to maintain capital ratio according to Basel requirements. Doesn’t the income from govt.bond interest payments improve banks capital ratios, which in turn would improve their capacity to Lend.

If customers deposits’ show up as liabilities on a bank balance asset sheet, why do they chase depositors?

“Investors can always borrow if they are credit-worthy”

I don’t get this. The same Mortgage borrowers in 2007 were considered credit worthy, were then in 2009 considered risky.

Many Businesses which were viable failed during the credit crisis due to credit lines being stopped by banks, leading to business failure and unemployment. Hence “Credit crunch”. Banks across the economy had decided that formerly viable businesses were no longer creditworthy. My understanding of the GFc is that Banks could no longer provide easy credit to business due to over indebtedness on the Banks part. That was how a financial sector ‘credit crunch’ translated into a real economy recession and high levels of unemployment. The interbank lending market froze due to banks owning too many toxic assets, famously the mortgage backed securities which were spliced together by investment banks and given AAA ratings by the rating agencies, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s, and Fitch Group. These rating agencies were paid by the investment banks to give these toxic assets high ratings so that they could be sold off to other banks. Obviously the situation had a conflict of interest as the rating agencies were financially incentivised to give these assets high ratings. The investment banks paid them to do this as it enabled them sell it off at a premium.

As the interbank lending market froze up, many banks could no longer functioned. Lehman brothers and Northern rock, as they could no longer maintain capital ratios. But more importantly many Banks stopped providing credit to business, even though the real economy had no obvious changes. Again the banks messed their capital ratios, owing too many toxic assets, hence the central banks programs in Ireland and US (T.A.R.P) to mop them up to improve Banks’s assets sheets. The fact that banks had too many toxic assets caused them to no longer be able to lend to viable businesses.

So how did the real economy business suddenly become un credit worthy over the credit crunch even though the initial problem in the economy originated from a contagion of risk in the Financial sector and poor practices from investment banks and credit rating agencies. How did the real economy of production consumption and employment suddenly become uncreditworthy when the only problems in the economy were down to banks owning too many worthless Mortgage backed securities,Collaterlised debt obligations and derivatives.

In layman terms this is the way I see the last recession: Businesses could no longer access credit or affordable credit as the banks had a credit crunch (all the newscaster were saying the cost of credit had gone up).Due to the banks lacking confidence in the interbank market they pushed up interest rate on credit which in turn led to small businesses having to close and fire staff. The rising level of unemployment actually led to a fall in demand and consumption which in turn created the real recession as firms saw a drop in consumption as consumers had lost their jobs and or started paying off debt.

So the viability and real credit worthiness of the Businesses were undermined in the first place by banks choosing to make lending more expensive, as they were concerned about MBS’s, CDO’s(many originated from foreign economies) etc. This is what created the real recession!

Banks continue Malpractice like this; RBS has history of killing off its firms to acquire assets and selling them off through its derivative Global Restructuring Group in order to improve its Capital ratios.

The criteria of Credit worthiness should not be left to banks which lend on the basis of their own asset balance sheet and liquidity and health of the interbank markets. The recession saw many viable businesses finished off by banks, due to banks own fiscal insecurities.

A big part of commercial viability in the real economy depends on lending conditions, cheap affordable credit gives business a decent chance. Banks have to be supportive and give firms breathing space. On the macro level cheap commercial credit allows businesses to prosper which in aggregate will increase employment and therefore consumption and demand.

If “Investors can always borrow if they are credit-worthy” then what is a credit crunch??

even Wikipedia describes it as a slow down in lending “A credit crunch is often caused by a sustained period of careless and inappropriate lending which results in losses for lending institutions and investors in debt when the loans turn sour and the full extent of bad debts becomes known.” created by the banks balance sheet problems.

I thought even Minsky credit cycles should how asset prices rises and a debt overhang followed by a sudden drop off were all created by bank and private debt.

To me it seems if the Banks frequently demonstrate an inability to correctly determine the worthiness of an investment. Then how could it be said that credit worthy investors will always be able to access credit when the credit crunch demonstrated how firms lost access to credit.

To me it looks like this: the banks bid up asset prices and lend generously for property and business. In aggregate, across the whole economy they were no longer able to lend at the same levels due to their balance sheet problems leading to a real recession.

Well would the MMT position be that if the government ran fiscal deficit then Investors are more likely to become credit worthy and banks will therefore be able to lend. Whereas during recessions created by private debt growth and the government running to low a fiscal deficit then banks will not lend.

As investors will be less likely to payback to loans in a low deficit and high private debt economy, banks are correct to deny credit to investors in those macroeconomic conditions.

So while the problem first appeared in the banks ,essentially the problem was initially an insufficient deficit forcing growth to be fuelled by private debt in the first place.

I would appreciate it if people could help me understand this issue,Thanks

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=3225

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=28270