I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Time to ditch the export-led growth mania

Last week, the former head of the Australian Treasury, Ken Henry gave a speech at the Australian National University entitled – Writing a New Australian Story – which received considerable press coverage. His message has relevance to all advanced nations who are engaged in a war on their population via fiscal austerity and attacks on workers wages and conditions as a enhancing so-called international competitiveness and engendering an export-led recovery. He considers these things are fine but not as ends in themselves and successive Australian governments have forgotten that message and undermined our national prosperity as a result. He believes it is time to reorient the public debate to focus on the challenges ahead rather than be mired in single-minded goals that only help a small sector of our society. I agree with some of what he says but we reach the same conclusions from an entirely different body of economic understanding. I had a 4-hour flight today on my way up to the North of Australia and this is what I wrote on the journey to keep myself amused.

By way of background, Australia like most nations has been caught in the IMF-led spell of export-led growth strategies. These are extolled as almost the epitome of virtue because they provide a smokescreen for an ideology that opposes government-led stimulus aimed at promoting domestic demand-led growth.

The latter was a major component of the Post World War II full employment era, which didn’t eschew developing robust export sector but also knew that if national prosperity was to be maintained and developed then a strong government role was necessary to build public infrastructure, directly employ people to provide services using that infrastructure and also those who were left behind in one way or another by the private market economy.

It was an era of falling income and wealth inequality, jobs for all whenever, growing real wages in line with labour productivity growth, and accordingly, improvements in health, education and general prosperity.

But it was also an era that the captains of industry – then the old-industries – manufacturing, steel, chemicals etc – were forced to compromise on their never-ending lust for more power and wealth.

Social democrat governments emboldened by the Post War quest for ‘democracy’ and ‘inclusion’ stood between the workers and the bosses – walking a tightrope between their conflicting aims. I wouldn’t say for one minute that this circus feat was even-handed.

Lobbying from the elites of capital saw that the governments (and the competing political parties) remained captive in one way or another. But the political processes were less influenced by the 24-hour news cycle and the media manipulation of the likes of the filthy Murdoch camp.

The rapport between the politicians and the people was mediated in old-style town hall meetings and the like, which is why modern politicians, particularly Americans, think they can appear legitimate if they engage in some grass roots campaigning.

The fact is that people demanded full employment because the War had embued a collective will – we were all in it together and a job for me should be a job for you. We believed in eliminating poverty and giving everyone a chance.

Politicians had to resist falling completely captive to capital, who hated full employment. Otherwise, they would lose office. If you examine the political mantras of the 1950s up until, maybe the mid-1970s, you will see how different they were when compared to the narrative of today.

Even the Republicans in the US, the Liberals in Australia and the Conservatives in the UK, and all the rest of the pro-business political parties couldn’t escape this reality.

But then things changed. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system in August 1971 (although it was not formally abandoned until a few years later) changed things considerably.

One of the big changes was that the IMF lost its raison d’etre as soon as the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates collapsed. The IMF was created as a core institution within that system as part of the Post War quest for stability.

It role was to provide funds to nations that were struggling to maintain the fixed parities agreed by participants in the system. It was Keynesian in outlook, which meant that it knew that full employment was the best goal that a nation could pursue.

At the outset, its loans were largely unconditional, although that changed somewhat towards the end of the 1960s, as the neo-liberal ideology that now dominates the economic thinking was starting to emerge. But the idea that the nations would be subjected to harsh austerity demands just to access IMF funds, that they had, in part, contributed to as part of their quota as members of the Fund, was alien.

But after 1971, flexible exchange rates became the norm across most economies, which meant that trade and capital flow imbalances would be mostly resolved by instantaneous shifts in the exchange rate rather than the previous situation, whereby nations with current account deficits had to scorch their domestic economies to quell imports and/or reduce inflation rates, just to take pressure of the exchange rate so they could maintain their parities as agreed.

In the new flexible exchange rate world of fiat currencies (not backed by gold nor convertible into gold on demand), the IMF suddendly had no meaningful purpose to fulfil.

In his 2002 book, Joseph Stiglitz provided a fascinating account of how the IMF sought to dominate thinking about economic policy in both developed and developing countries to give it a new role to play.

Not only did he strongly criticise the ‘one-size-fits-all’ nature of the IMF policy prescriptions, but he also observed that (page 42):

The IMF is like so many bureaucracies; it has repeatedly sought to extend what it does, beyond the objectives originally assigned to it. As IMF’s mission creep brought it outside its core area of competency in macroeconomics, into structural issues such as privatisation, labour markets, pension reforms and so forth …

He argued that the combination of the IMF’s fierce promotion of the current dominant neo-liberal ideology in economics, its simplistic yet well-defined policy framework and its good political contacts in the Western world, has rendered it a very powerful institution, which often usurped the World Bank’s role in its dealing with poor countries. Stiglitz was also critical of the World Bank but that is another story.

[Reference: Stiglitz, J.E. (2002) Globalization and its discontents, London, Penguin Group].

The IMF became one of the neo-liberal attack dogs. Governments could hide behind the anonymous, unaccountable face of the IMF to push back social democratic forces and accept more easily the fact they were captive of capital, increasingly, international in scope and empowered commensurately.

The captains of industry also started to see a shift in their membership – the old school, the old money, started to see some loud-mouthed, upstarts entering their power spectrum. The era of the financial capital elites had begun in earnest.

This is not to say that the bankers were not without influence prior to this. Of course they were. But with the opening up of global financial markets, courtesy of the collapse of the fixed exchange rate system, a whole new range of options was available (derivatives etc) to speculate with and against, and the bankers more easily were recognised as banksters.

The OECD went through a similar metamorphosis. You might recall that the Paris-based organisation was set up after World War II, to help reconstruct Europe under the Marshall Plan. Its name tells you that it was established to foster ‘Economic Co-operation and Development’.

It was firmly Keynesian in the 1960s. But it jumped with the IMF to become another attack dog for the neo-liberal policy agenda and its particular role is exemplified in the OECD 1994 Jobs Study which set the framework by which government abandoned their commitments to full employment and, instead, started promoting and pursuing the diminished role of ‘full employability’.

Unemployment shifted from being a systemic failure to create enough jobs to a failing of the individuals who were jobless. Increasingly moralistic overtones entered the debate and public narrative. The victims of the system failure were now characterised as indolent, lacking motive, aspiration, endeavour and, seemingly content to enjoy the ‘high life’ on the pittances that were provided by way of income support.

The rest of us fell for it, which is more our shame. But to be fair we were bombarded almost daily with a media onslaught promoted by these elites and self-serving politicians in their captive that if someone wanted to work they could always find it and what right had they to live on the efforts of the rest of us.

We all hated work (mostly) and would much rather be out surfing or lying around watching TV. So why should the lazy unemployment take our ‘taxes’ and live it up.

It was a nonsensical narrative but such is the nature of mass media indoctrination it has proved to be a very effective one.

The elites promoted it because it they hated full employment. Marx was never more correct in his analysis of the functional role that unemployment plays in keeping wages growth low and helping the capitalists get their hands on a bigger share of real income.

As trade unions were corralled by various legislative changes and large pools of unemployed were created by governments abandoning the use of fiscal deficits to ensure there were enough jobs available to match the desires of the available labour force, the capitalists started to enjoy higher profit shares via the growing gap between real wages and productivity growth.

The OECD is at the centre of that despicable attack on human rights.

The economic narrative has become homogenised in the 1970s after the big OPEC oil price hikes had created mayhem in advanced, oil-dependent nations. The dislocation gave the neo-liberals the cover they needed to attack the Keynesian consensus that had underpinned the commitment to full employment.

We were all individuals. There was no such thing as society. Leaving the ‘market’ to do its job would maximise our individual prosperity – all of us.

I examined the rise in homogeneity of thinking or cognitive bias in my book on the Eurozone, which will be published in both English and Italian versions in early 2015.

The major economic institutions and the policy makers were trapped in Groupthink, which refers to the way self-reinforcing group dynamics ensure that only certain issues are considered to be important and matters that challenge the underlying premises of the ruling paradigm are actively eschewed.

Economists and policy makers were trapped by the peer-group belief that self-regulated private markets would always adjust to avoid any economic crisis. Within that intellectual prison, there was simply no need for strong fiscal agency or regulative structures.

By the end of the 1980s, this view was dominant in the academy and had infiltrated the major multilateral institutions (for example, the IMF, World Bank, OECD), treasuries and central banks across the advanced world.

Economists and policy makers were trapped by ‘confirmation bias’, which refers to the dynamic whereby people only admit as ‘fact’ information that reinforces their own world view and refuse to acknowledge other information that might challenge that view.

Groupthink dominated Governments all around the world as they ignored the persistently high unemployment that the deflationary biases in economic policy had caused. Worse was to come in the GFC, particularly in Europe.

The neo-liberal economic framework promoted vigorously by many economists, the multinational agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and conservative politicians including the Eurozone establishment in Brussels and Frankfurt, blinds the public eyes to realistic alternatives by deliberating confining the boundaries of the public debate through the use of selective priorities, wrongful causalities, and scandalous misrepresentations of reality.

And as part of this process of obfuscation, the export-led and competitiveness mantra became an important plank to justify the reduction in government function and oversight.

In his speech last week, the former Australian Treasury head, Ken Henry touched on some of these themes, although I would not say he would share the way I would tell the story. He is a neo-liberal but is also a thinker rather than a shame-faced ideological operative.

His speech outlined how, as part of the growing neo-liberal anti-government narrative, Australia was caught up in new ideas, fiercely promoted by industry groups and politicians that mimicked their demands.

The Labor government, which assumed office in 1983, led the way in laying the neo-liberal policy foundations in Australia. The Labor Party had been established to be the political arm of the trade unions. By the 1980s, it was full of university-educated spivs who hadn’t done a day’s manual labour in their life. Lawyers, etc and they longed to become part of the elite themselves.

So they did the bidding of the capitalists. The second-half of the 1980s was dominated by claims that the only way to achieve prosperity was for the workers to accept real wage moderation, which became orchestrated real wage cuts under the so-called Prices and Incomes Accord.

As an aside, the bosses never formally signed up to the Accord so profits were excluded from the ‘incomes’ that were being moderated. And, further, the government quickly learned that under our constitution it couldn’t legally control prices anyway.

In other words, the fabulously named Prices and Incomes Accord became a wage guideline and by the latter parts of the 1980s it became a real wage cutting tool.

The unions signed up to it as they lost their compass. This was an era of growing corporatism in the unions and some union leaders started to resemble industry bosses in their demeanour and appeared to be more comfortable eating and drinking in corporate boxes at major sporting events than wandering around the shop floor seeing what concerned their membership.

The wage cutting narrative was accompanied by claims that if we achieved higher levels of productivity and competitiveness, redistributed national income to profits, and cut tariffs and freed up trade markets, there would be an investment and export bonanza and workers would reap the bounty.

The then treasurer, Paul Keating, himself a spiv who had left his working class roots behind long ago, led the chorus and called on all of us to modernise and become an export-led nation of untold wealth and reward.

Suddenly, there were trade union delegations to Scandinavian nations to learn how to become an export powerhouse. Lots of long and well-catered for lunches and expensive wines were no doubt consumed during these ‘study tours’.

In July 2014, the peak body, the Business Council of Australia released a major report – Building Australia’s Comparative Advantages

The whole tenor of that Report was that:

… the next decade of growth must be one where Australia comes to terms with an increasingly dynamic and global marketplace … [and] … The only way to guarantee success in this world is to be competitive at a world standard.

Its concept of public policy was as follows:

Governments should be facilitating competitive industry sectors by taking a sector view of the economy and prioritising all decisions and reforms to promote Australia’s comparative advantages.

Export competitiveness becomes the priority! This requires among other things, reducing regulations on business practices (meaning policies that protect the environment, promote honesty etc), “reducing labour market rigidities” (meaning job protections, wage rules etc), “Developing physical infrastructure” (meaning – using the public purse to build infrastructure purely to benefit business without being able to capture the appropriate social returns), etc

It was in this context that Ken Henry delivered his message and asked “how should one assess the wealth of a nation; and what are its policy determinants?”

Reflecting back on Adam Smith and his ‘Wealth of Nations’, Henry told his audience last week that:

Like Adam Smith, we know that mercantilism is misguided. The idea that public policy should be organised to protect and advance the interests of exporters has no support in economics.

And yet, in Australia today, 238 years after the publication of The Wealth of Nations, the dominant economic narrative goes like this: reforms that enhance productivity and cut costs build international competitiveness; international competitiveness drives exports; exports drive growth; growth drives jobs; and jobs support living standards.

He went on to say that the export-led mantra that has dominated the last three decades has undermined our best interests as a nation.

As a result “we are now paying a price for past expedience. The mercantilist narrative is so deeply entrenched that it is crippling sensible attempts to deal with some of our biggest challenges.”

He then focuses on the concept of real exchange rates.

Ken Henry told his audience last week that it was clear the fortunes of the nation were tied intrinsically to our capacity to back our export industries, which were dominated by mining and agriculture.

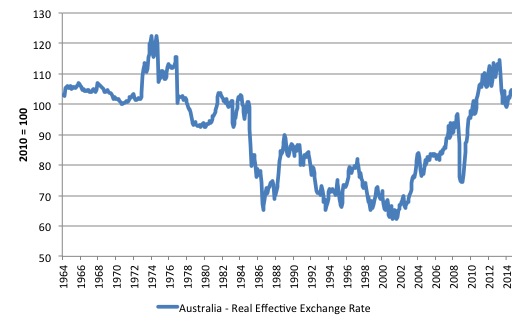

The following graph confirms the loss of international competitiveness for the Australian export sector. Its shows the movements in the Bank of International Settlements monthly Effective exchange rate indices – from January 1994 to August 2014.

You can learn about this data from their publication – The new BIS effective exchange rate indices – which appeared in the BIS Quarterly Review, March 2006.

There was an earlier publication – Measuring international price and cost competitiveness – which appeared in the BIS Economic Papers, No 39, November 1993.

Real effective exchange rates provide a measure on international competitiveness and are based on information pertaining movements in relative prices and costs, expressed in a common currency. Economists started computing effective exchange rates after the Bretton Woods system collapsed in the early 1970s because that ended the “simple bilateral dollar rate” (Source).

The BIS say that:

An effective exchange rate (EER) provides a better indicator of the macroeconomic effects of exchange rates than any single bilateral rate. A nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is an index of some weighted average of bilateral exchange rates. A real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted by some measure of relative prices or costs; changes in the REER thus take into account both nominal exchange rate developments and the inflation differential vis-à-vis trading partners. In both policy and market analysis, EERs serve various purposes: as a measure of international competitiveness, as components of monetary/financial conditions indices, as a gauge of the transmission of external shocks, as an intermediate target for monetary policy or as an operational target.2 Therefore, accurate measures of EERs are essential for both policymakers and market participants.

If the REER rises, then we conclude that the nation is less internationally competitive and vice-versa.

The movements in Australia’s international competitiveness is driven by the shifts in the nominal exchange rate rather than disparate inflation trends between Australia and the rest of the world. Please read my blog – Manufacturing employment trends in Australia – for more discussion on this point.

But what point was Henry trying to make?

The deregulation, wage cutting regime was ratcheted up and miners started to reap even greater profits from extracting our minerals and shipping them to China and Japan (mainly). Governments gave them such ridiculous concessions, especially considering how much of the capital in the industry was foreign-owned.

Ken Henry has now challenged this narrative.

According to Henry, Australia workers and society in general have been caught out twice by this mantra.

As noted above, workers real wages were cut to deliver the export competitiveness in the 1980s. Henry outlined how wage indexation was abolished (which led to the real wage cuts) and tariffs were reduced severely (which led to widespread job losses).

He notes that:

… there was another, complementary, piece of the narrative developed in Australia in the 1980s: a tighter fiscal policy would improve the prospects of a real depreciation, further boosting exports, and export growth would cause the current account deficit to narrow, thus dealing with the threat posed by ever-increasing international indebtedness. Thus was born the sub-narrative of ‘debt and deficits’, part of the broader story of Australian mercantilism.

Now, after a boom in world commodity prices that led to the so-called Mining boom, Australia has experienced a rise in its real exchange rate as documented above – “in the order of 50 per cent”, which has “damaged our international competitiveness”.

So what has to happen now?

The mercantilist narrative is driving:

… various proposals designed to reverse the real currency appreciation caused by international commodity price inflation: cut business costs, especially wages and taxes; boost productivity; and cut government spending.

He says doesn’t that “sound familiar” – cut wages, cut government spending.

His conclusion:

No matter what the malady, Australian mercantilism will always prescribe the same treatment. And of course it must, because no volume of exports will ever satisfy a committed mercantilist.

Ken Henry didn’t say we should abandon helping exporters. But he said we should realise that it wasn’t an end in itself but should be seen as a means to improving national prosperity.

He listed a number of sub-narratives that are undermining the way we meet the challenges of the future.

He notes that the export competitiveness story has damaged the capacity of governments to implement new taxes to deal with things such as carbon use.

Of great importance to the mercantilist narrative is the promotion of cheap energy as a way of ensuring the Australian economy maintains its export competitiveness.

In the 1970s, we were led to believe that cheap energy was good because it allowed industry to lower costs and become more competitive.

The trend as climate change becomes more obvious is to force industry and households to pay the ‘full cost’ of the energy they consume, which means the environmental damage of extracting and using that energy has to be included in the price to discourage use.

The current conservative government has moved in the opposite direction, appealing to what might have been acceptable in the 1970s when less people were concerned or had any knowledge of what the environmental damage was and would be.

So we saw the rescinding of the Carbon Tax and last week the Industry Minister told a leading neo-liberal economic conference (CEDA) at their – CEDA Energy Series: that

… issues relating to energy and energy market reform are central to our economy, because access to affordable and reliable baseload power has long been one of Australia’s most potent competitive strengths. It will be equally as important in building the industries of the future.

He went on to recite the mantra – “Competitive markets should drive pricing, supply contracts and project investments” and “Our abundance and diversity of energy supplies has given Australia the opportunity to firmly establish itself as an energy superpower” (read: coal).

And – “our Government’s predecessor … not only eroded our competitive edge in energy markets, but actively sought to put a handbrake on our energy industry through policies such as the carbon tax and the mining tax.”

The Prime Minister keeps batting on about Australia becoming an “affordable energy superpower” and that we need to make energy as cheap as possible. Exit Carbon Tax and enter promotion of the coal industry – a leading exporter.

The Government also set up a review of the Renewable Energy Target (Warburton Review) which reported in August – Renewable Energy Target Scheme Report.concluded that (page 43):

However, access to cheap and reliable power (historically, predominately provided by coal) helps to underpin Australia’s economic growth and Australia needs to balance its emissions reduction efforts with the need to maintain this source of competitive advantage.

So the link between environmental vandalism and the export competitiveness mantra is entrenched and dominant.

His solution is to introduce “a more honest narrative”.

Conclusion

I haven’t time today to outline his full plan because I disagree with much of it.

But I agree that government policy should avoid “short-termism and has no taste for protecting vested interest; a place in which governments have the intellectual capacity and political courage to articulate a compelling vision of what could be.

That vision should see a return to placing full and decent employment at the heart of policy goals within the context of environmentally sustainable development.

But it is unquestionable that:

The public policy of Australia should be directed to ensuring that all Australians, including those not yet born, are endowed with the capabilities that afford them the opportunity to choose a life of value. That is the measure of the wealth of Australia and also of the sources of its wealth.

We are a long way from that both in Australia and elsewhere.

Organisations such as the IMF continue to bully governments into accepting the export-led narrative. Part of the problems the Eurozone are experiencing relates to the dominance of that narrative with the distinctly German bias.

I could go on and talk about Africa etc but we just landed.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Thanks for the history lesson behind this thinking and the term ‘mercantilism’.

Running external sector ‘trade’ surplus (larger and larger depending on which politician mentions it, wether they are currently elected or in opposition 😉 ) is a hot topic in europe too. Its Labors plan in the UK and a lot of talk about it in France and Italy too.

They expect to ‘reform’ their stagnant economies (without any fiscal policy), just by deregulating a given market more, then each state ignoring identical aspirations such that everyone will be running ‘trade surplus’ and live happily ever after. Use of the word insane but it just doesn’t cover the levels of stupidity and double think thats involved.

How is that belief compatible with the neo-liberal belief in the NAIRU?

If they believe that unemployment can’t be below a certain level without being inflationary, and they believe that inflation is always caused by government “printing money”, doesn’t that implicitly acknowledge that employment is the result of government deficit spending?

or is that tale about people always being able to find work if they wanted to only propaganda to feed the masses with?

Dear Bill

If all countries try to become richer through export-led growth, then we are back at mercantilism. Still, if a country without industry wants to industrialize, it needs to import more. To finance these imports, it will have to export unless it can obtain credit. Industrialization for a newcomer requires imports because the country has to import various machines and sometimes raw materials and energy as well. Even if a less developed country knows how to manufacture shoes and textiles, then it may not know how to manufacture the machines for the production of shoes or textiles, which then have to be imported.

Suppose that Peter owns fertile but virgin land. He wants to convert it into a farm, but he has no capital. How can he acquire the machines, the seeds, the fertilizer to his land into a farm? He will have to export something else (work more hours for example) or else rent out the farm or borrow money. Countries without industry can be compared to Peter. Renting out the farm is like acquiring foreign investment and borrowing is like importing capital.

In short, the notion of export-led growth is not totally absurd for unindustrialized countries that wish to become industrialized. We just have to bear in mind that the exports, like all exports, are necessary only to finance the need of imports arising from industrial growth, not to create jobs.

Regards. James

I think the term “export-led” growth is sort of misnomer there, it should be “import-led” growth instead. Also, there is no need for trade surpluses.

“To finance these imports, it will have to export unless it can obtain credit.”

A common misconception.

If an export led country wishes to open up a foreign market, it need only offer ‘liquidity swaps’. That means the exporter can take the import country’s currency in payment for the goods, with the export led country ‘swapping’ that into its own currency either ahead of schedule or afterwards depending upon the particular way they want to hide the practice.

Exporting is seen as a legitimate way of deploying your own currency. Essentially your own central bank buys your goods and services and gives them to the import nation in return for extracting some of their own money from circulation. That’s a win-win for the export nation. The import nation is deprived of circulation of its own money (because neo-liberal theory won’t allow it to be replaced – deficits are *bad*) making it less likely they’ll develop a competitor. The export nation stimulates its own economy by deploying its own money and holds down the exchange rate – again helping the export nation’s economy boom.

The correct approach of the import nation would be to take advantage of this madness and just keep stimulating its own domestic economy while taking the goods and services from the mercantilists.

A clever leader of a country could easily play the export-led nations for the fools that they are. All they have to do is understand how it works.

Neil Wilson

While it is true that the sensible thing would be to keep stimulating its domestic enconomy, it is still sensible to aim to export more. The alternative is a long term decline in its currency’s value.

Currency depreciation itself drives exports, so that really cannot be the primary aim.

Stimulating your domestic capacity increases your export capacity anyways.

Aidan Stanger & hamstray, export will only work if there is someone who can afford to import. But if everyone is in the same sinking boat, only building up one’s domestic economy will really help. Being able to export would be a nice bonus.

hamstray, there will always be something that drives exports, but a long term trend of currency devaluation is something best avoided.as it will reduce wealth. It’s also likely to be inflationary, which will erode the extent to which it does drive exports.

Stimulating your domestic capacity is likely to increase imports more than exports.

larry, as you’re importing, it’s safe to assume someone else can afford to do so. But even if everyone were in the same sinking boat, foreign investment would enable exports to be sustained long enough for the situation to change.

Bill –

They’re sort of right on this one! Australia is a big sunny country, so cheap (solar) energy is one of the strengths we really should compete on.

dear Bill

Wonderful blog.

Of course you are right about Ken Henry. He remains a neo-liberal, but like some of the same kind in the US (e.g. Paul Krugman) perhaps, gradually, is being mugged by reality. Anyway, as a result of your blog, I am going to work my way through his speech. By the way, if you had time it would be good to have your views on where he is right and wrong.

Incidently, the OECD,which I had a lot to do with when I was a trade bureaucrat, began its life as the OEEC (Organisation for European Economic re-Construction). Its purpose was to ensure the Marshall Plan funding was not misspent. (And, as I’m sure you know, the Marshall Plan was only needed because Keynes’s plan for an international currency was rejected by Harry White during the Bretton Woods Negotiations.

Once the purpose of the Marshall plan was achieved there was no further need for for the OEEC.

But bureaucracies do not voluntarily self-destruct; so the OEEC became the OECD, first attached to Keysenism and later, following economic fashion,embraced neo-liberal.

regards

Colin Teese

Spot on Bill. I am old enough to remember all the history from 1970 first-hand. I also read history, which everyone should do, so I know that the TINA mantra of the neocons is a complete lie. There are many alternatives to our current policies; policies which have been failing us for 40 years.

“The Labor government, which assumed office in 1983, led the way in laying the neo-liberal policy foundations in Australia. The Labor Party had been established to be the political arm of the trade unions. By the 1980s, it was full of university-educated spivs who hadn’t done a day’s manual labour in their life. Lawyers, etc and they longed to become part of the elite themselves.”

That is oh so true. I call them the “Betrayal Party” now. They betrayed the workers. I was a worker so I can say this. I did labouring and machinery operating in farming, quarrying and extractive industries in the private sector. Then I did clerical banking work in the private sector. Finally I did clerical and computer systems work in the Public sector, namely federal welfare in the old DSS (Dept of Social Security). I will never forget how the modern Labor Party betrayed us, the workers. They are all rats. From the LNP I expect no better. They are the attack dogs of oligarchic capital. They are selected for what they do. But the betrayal by Labor was and is unforgivable. I always makes sure I put LNP, Labour and parties created by billionaires at the bottom of the ballot paper along with all the other crypto-fascists.

«”The Labor government, which assumed office in 1983, led the way in laying the neo-liberal policy foundations in Australia. The Labor Party had been established to be the political arm of the trade unions. By the 1980s, it was full of university-educated spivs who hadn’t done a day’s manual labour in their life. Lawyers, etc and they longed to become part of the elite themselves.”

That is oh so true. I call them the “Betrayal Party” now. They betrayed the workers. I was a worker so I can say this. [ … ] I will never forget how the modern Labor Party betrayed us, the workers. They are all rats.»

That is very similar to the UK experience, but Bill Mitchell and you forget a very important detail indeed: the people who betrayed the workers have been the workers themselves, the mass spivs who have cashed in massive tax-free capital gains by speculating on property for 30 years.

If you do the arithmetic, the enormous property price boom has generated for very many workers who finally got nice houses in the suburbs thanks to social democratic policies something that changed their modes of thinking: tax-free capital gains equal to 50-90% of their after-tax income *every year* for decades, with yearly *net* returns of 40-70% a year on cash invested.

When a worker gets that sort of money from property speculation they get to to think that they don’t need trade unions, they don’t need wage raises, they don’t need pensions, they don’t need good jobs, they don’t need unemployment insurance! Those are just what losers want, and they are winners!

They get to think that winners just need to vote for people like Thatcher and Abbott, Keating and Blair who just deliver to “aspirational” middle income property owning voters the massive tax-free capital gains they want. In particular if the are middle aged or retired women, divorced or widowed, who own most large family houses in the suburbs.

Bill Mitchell like so many deluded fools on the left thinks that “workers” have been swindled by the propaganda of the media; but most “workers” vote their wallets, or rather vote their property capital gain “aspirations”, because that involves a lot of cash going into their pockets. Their politics are not “export led growth”, they are “F*CK EVERYBODY ELSE! I GOT MINE!”.

The “workers” once joined the ranks of the lower middle class fancies themselves landladies of the manor, people of quality, with more in common with billionaires than with poor, whom they saw as exploitative and parasitic.

I have collected a lot of quotes to support the above, but the best is from England, from The Times, 2011-09-17, a piece titled “Women are taking a hit and they are angry” by Janice turned, about UK electoral politics:

«The C2 women who voted Conservative last time did so because they, in low to middling-paid roles such as nurses, secretaries and carers, believed welfare had grown too generous, that benefits rewarded the do-nothings while they toiled. They hoped the Tories would crack down.

Now, they are shocked to discover the Government regards them as part of the problem. They work in the “bloated public sector”, their meagre pensions are grotesquely lavish, their often tough vocational jobs are regarded as worthless and dispensable. Labour celebrated “hard-working families”; the Tories tell them it was their salaries – not the bankers’ excesses – that broke the economy.»

Note that these middle aged and older C2 women (most of them until then with secure government jobs and ever appreciating properties) wanted a crackdown on nasty creepy young men scrounging on the dole during the worst recession in almost a century. They want the crackdown on those losers because they are after all keen to keep their public sector jobs, and clamor for savings in budgets to be made at the expense of someone else.

It all goes back to a very important study by a right-wing think tank at the end of the seventies that demonstrated that:

#1 higher income/class people who rented, used public transport, had pensions vote for the left, as if they had a lower income or class.

#2 lower income/class people who owned property, owned a car, owned a share account vote for the right, as if they had an upper income or class.

Numerically #1 is a small effect. But #2 numerically is a very big effect, and it has been relentlessly pushed forward, in a massive and very successful project of social engineering.

It is “workers” who have betrayed the left, rather than viceversa.

Keating and Blair, as Blair and along with him Giles Radice have written very eloquently, have simply followed that trend by appealing to the many “workers” who have become petty mean tory spivs.

Export competitiveness is on the frontline of the capitalist strategy to win

the battle for surplus value.

The problem of course is killing the golden goose .

Much speculation in the press (Preston on the bbc blog today etc)

about the end of growth in the devolved world which essentially boils

down to how can you maintain decent growth in mass consumer economies

when the spending power of the masses is stagnant if not declining?

Private sector credit boom ?Didn’t end well last time.

Anything but utilizing the monetary power of the state of course.

Still uneasy with advocating an import strategy what is good for the goose

is surely good for the gander .I am sure Chinese workers could benefit from the spoils of their

labour not to mention resource wasting shipping costs

Only ‘mug’ nations net-export to the ROW. Exports are what a nation gives up to obtain imports. Hence, exports are costs; imports are benefits. When a country net-exports, it gives up more useful stuff to the ROW than it gets in return. In the process, it ends up using and consuming less useful stuff than it digs up/harvests/produces itself (i.e., it consumes less then it produces).

There is only one reason why a nation would net-export – there is insufficient net spending by the nation’s central govt to enable the domestic private sector to finance its current spending and net-savings desires. For example:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

If G – T = 0 (balanced budget), then X > M (net exports) is necessary to enable S > I (positive net savings of private sector)

If G > T (budget deficit), then S > I is possible when X = M

The second case involves the central govt effectively purchasing the real resources/g&s that were earmarked for net-exporting (i.e., the difference between X and M). This enables the private sector to satisfy its spending and net-savings desires. It also means that the real stuff that would have been net-exported remains in the country to build additional hospitals, schools, universities, etc.

So long as the price paid by the central govt for the real stuff that would have been net-exported is the same as the price that would have been paid by the ROW, the increased net spending by the central govt is not inflationary. Moreover, as anyone with a sound knowledge of public finance knows, a currency-issuing central govt has no problem finding the domestic currency needed to finance the necessary increase in its net spending. Even better, it need not charge the nation’s citizens to access/use the additional public goods.

China has been a ‘mug’ nation for some time. It has woken up to this and is now focusing attention on increasing its consumption:GDP ratio. The Western World has benefited from China’s stupidity in the past, but not for much longer. As China starts to consume more of what it produces, many de-industrialised European countries will be reduced to basket cases unless there is a massive increase in central govt spending to rebuild their infrastructure. That’s unlikely in a present-day EU.

Phil Lawn, do you think that only ‘mug’ humans net save? If not, what’s the difference?

Your simplistic argument has ignored a few key points: firstly trade benefits both parties involved, as each gains something that’s more valuable to them than what they give up is (otherwise they wouldn’t bother). Hence both imports and exports bring net benefits.

Secondly you’re ignoring the effect that imports and exports have on currency values.

Thirdly net exporting is likely to reduce currency volatility because it makes currency value less reliant on foreign creditors.

Aidan:

A ‘smart’ nation would ensure trade is balanced, encourage the private sector to net save, and have a central govt willing to net spend to the level required to accommodate the private sector’s spending and net savings desires (i.e., (G > T) = (S > I) – (X = M)). This would also enable the nation to maintain financial stability, achieve f/e, and not give up more useful stuff to the ROW than what it gets in return. It would also benefit from international trade (i.e., MB of stuff given up < MB of stuff received). 'Mug' nations are those where the central govt doesn't do this (usually because of some false belief that currency-issuing central govts can't keep running deficits), and thus force the private sector to net-export to enable it to satisfy its spending and net savings desires.

As for trade benefiting both parties – well of course trade is designed to benefit both parties (as just described), but would you prefer to give up more useful stuff than what you get in return simply to obtain a financial asset denominated in a foreign currency for savings purposes if the former could be avoided by having your central govt net spend to adequate levels? Of course you wouldn't!

The reason why, in the aggregate, the private sector of a net-exporting country bothers to net-export is because, without it, the inadequate net spending by the central govt forces the private sector, if it is stubbornly determined to maintain its spending desires, to abandon its net savings desires (i.e., (S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M) and so if, X = M, then G – T = 0 means the private sector must accept S – I = 0). Compared to this situation, net-exporting is clearly a better outcome. But that doesn't make it a desirable outcome when you have a central govt that could deficit spend to a level equal to earmarked net exports that would allow the private sector to: (i) maintain its spending and net savings desires; and (ii) enjoy the useful stuff that the central govt would initially obtain and could then hand back to its citizens free of charge in the form of schools, hospitals, etc. There are three possible outcomes here and you are comparing the second-best outcome with the worst outcome. The outcome I'm recommending is best. Are you suggesting that getting less in return from net-exporting is better than getting the difference between X and M returned to you from your central govt by having the central govt run a deficit? You may not realise it, but that's what you are suggesting. Like I said in my first comment, net-exporting is a very costly way of enabling the private sector of a nation to meet its spending and net savings desires.

Have you read the first chapter of an economics textbook that explains the rationale for trade/exchange? If you have, you have clearly forgotten that the example given always involves balanced trade/exchange. This is strangely forgotten when matters turn to international trade.

I'm not ignoring currency values at all – I just happen to think that, unless currency values are fluctuating wildly, the focus on exchange rates is pointless. Is the Australian dollar too high or too low? It's a meaningless question. If the value of the $Aus falls, it makes exports cheaper, but it also makes imports dearer. Exports are costs and imports are benefits. So if a nation exports more and imports less because its currency depreciates, it ends up with higher trading costs and less trading benefits in strict utility terms. People view X and M in perverse order because they develop a GDP-fetish. They fall into the trap of thinking that exports are good because they increase GDP and imports are bad because they don't. Well it's what you consume that matters not what you produce, as China has now woken up to. If spending is less than Yfe because net exports aren't supposedly high enough (resulting in u/e), it's not the lack of net-exports that's the problem – it's the lack of central govt net spending!

When you have balanced trade, foreign creditors aren't a major issue. They're no more problematic than domestic debtors. In any case, it's not the currency volatility that is of concern if you rely on net-eporting to keep GDP bouyant – its the volatility of your exports. That's not an issue when NX = 0 and when the central govt is always prepared to net spend to the level needed to keep total spending equal to Yfe (not a dollar less and not a dollar more, which could automatically be achieved by introducing a Job Guarantee). Adopting this approach also means that you can tell human rights-abusing countries what you think of them. If you upset a country and lose some exports, you import less – a cost that is worth incurring if you value the rights of people no matter where they reside. Balanced trade with G – T accommodating S – I is good for human rights. If this approach had been embraced and adopted long ago, perhaps there would be fewer terrorist cells emerging in response to an inequitable global economic and geo-political system that has long oppressed and alienated people.

Phil:

I strongly disagree that a smart nation would encourage the private sector to net save. Such encouragement is likely to involve the raising of interest rates, increasing the short term bias of business decisions. A smart nation would allow the private sector to net save but not encourage it.

The Australian dollar is overvalued, as imports still greatly exceed exports. It only got as high as it did because of the RBA’s paying over the odds for banks to park their money in Australia. That level was of course unsustainable and the market’s bringing it back down. But that correction appears to be happening on top of a further fall led by commodity prices. Falling quickly is far more inflationary than falling slowly.

To say “exports are costs and imports are benefits” is simplistic rubbish that ignores some of their most important effects. Exports make future imports more affordable. Imports make future imports less affordable.

«It is “workers” who have betrayed the left, rather than viceversa. Keating and Blair, as Blair and along with him Giles Radice have written very eloquently, have simply followed that trend by appealing to the many “workers” who have become petty mean tory spivs.»

Going back to the primary sources, this is a famous quote from one of Blair’s most important “vision” speeches:

http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=202

«I can vividly recall the exact moment that I knew the last election was lost. I was canvassing in the Midlands on an ordinary suburban estate. I met a man polishing his Ford Sierra, self-employed electrician, Dad always voted Labour. He used to vote Labour, he said, but he bought his own home, he had set up his own business, he was doing quite nicely, so he said I’ve become a Tory. He was not rich but he was doing better than he did, and as far as he was concerned, being better off meant being Tory too.«

I am pretty sure that the suburbs of Australia are full of people like that… And Blair continues the speech with hopeful words, but they don’t really apply. Another unimpeachable source:

http://www.conservativehome.com/thetorydiary/2014/03/how-thatcher-sold-council-houses-and-created-a-new-generation-of-property-owners.html

«It was indeed at the diffusion of property that inter-war Tories aimed, as the pragmatic answer to the arrival of democracy and the challenge from Labour. There were even prophetic council house sales by local Tories in the drive to create voters with a Conservative political mentality. As a Tory councillor in Leeds defiantly told Labour opponents in 1926, ‘it is a good thing for people to buy their own houses. They turn Tory directly. We shall go on making Tories and you will be wiped out.’ There is much of the Party history of the twentieth century in that remark.»

And the history of the left…

Blissex, this is why we need land value taxation.