The US is now a rogue state. One example is the conduct of the US…

G20 meetings and structure part of the problem

There are parallel universes operating when it comes to neo-liberal politicians attempting to deal with reality. The G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors concluded their weekend talkfest in Cairns yesterday and you might be excused for thinking there is a jobs glut across their economies. As an aside, fortunately, this pathetic lot of individuals were meeting about as far north as one can go on the Australian continent, which meant they were kept out of the civilised parts of the nation where the rest of us live. Given Australia is currently hosting the G20 this year, the event gave our buffoon of a Federal Treasurer the chance to bathe in the limelight and deliver the major press conference.

Mark Blyth in his 2013 book (page 100) – Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea – characterised the policy makers during the GFC as “Twelve-Month Keynesians” as their resolve to continue the growth process increasingly gave way to confused narratives about the need for growth friendly fiscal consolidation.

The increasing use of that narrative from 2009 onwards from the IMF, the OECD and other groups was of course a classic example of the law of contradiction where two propositions (growth) and fiscal consolidation (austerity) could not be true together given the collapse of private spending.

By 2010, there was an amazing reversal in the political rhetoric. At the Pittsburgh meeting of the G-20 leaders in September 2009, the Communiqué talked about the sufficiency and quality of jobs. The – Leaders Statement – acknowledged that:

… the national commitments to restore growth resulted in the largest and most coordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus ever undertaken … [but that the] … conditions for a recovery of private demand are not yet fully in place … [and] … We pledge today to sustain our strong policy response until a durable recovery is secured … We will avoid any premature withdrawal of stimulus.

There was even a proposal put forward by the then British Prime Minister Gordon Brown to radically reform the IMF, to ensure its resources were used to help nations rather than load them up with debt and onerous conditionality programs.

Less than a year later, the political leaders had abandoned that call and were advocating austerity policies, which would push unemployment rates up further and increase poverty.

This is in the context of dramatic increases in global poverty rates in 2009 due to income losses associated with entrenched unemployment.

The ILO publication – Global Employment Trends, January 2010 was a devastating indictment of how little was being done by national governments to reduce the spiralling global poverty rates as a result of the rising unemployment.

But that message was largely ignored at the June 2010 G20 Toronto Summit. The – Leaders’ Declaration emphasised:

… the importance of sustainable public finances and growth-friendly plans to deliver fiscal sustainability … countries with serious fiscal challenges need to accelerate the pace of consolidation.

Later that year, the annual G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting in South Korea issued a – Communiqué – which concluded that monetary policy should aim to:

… achieve price stability … [which thereby] … contributes to recovery … [and that] … ambitious and growth-friendly medium-term fiscal consolidation plans … [be implemented] …

The emphasis on fiscal consolidation and the need for ‘structural reform’ (aka as labour market deregulation) was affirmed at the G20 Leaders’ meeting in Seoul in November 2010.

The tide had turned and the anti-stimulus lobby had won the day. The rapid retreat from fiscal stimulus was exemplified by the UK macroeconomic policy response.

They were on the road to recovery courtesy of their fiscal stimulus package until the Cameron government took office in May 2010 and set about pushing Britain down the austerity path.

The British economy then laboured under continuous recession until modest growth returned in the first-quarter of 2013.

Six years later, the size of the economy (measured by real GDP) is still below the peak before the crisis.

Germany followed up the G20 meeting in South Korea by proposing an austerity plan for the G20 to endorse and the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said the measures might have to be “stricter than necessary”.

Think about that – ‘stricter than necessary’ – in the context that he is talking about the deliberate act of pushing hardship onto the most disadvantaged citizens in societies. Not only is he comfortable with doing that but he wants the punishment to go beyond what he thinks (erroneously) is necessary.

That is the sort of reasoning that sociopaths invoke in the policy setting context. Astounding really!

And so they met in Cairns in Tropical North Queensland. The – Communiqué – was as usual full of waffle.

They declared how growth friendly they all are and repeated the neo-liberal mantra that “structural reforms will be important” to lift growth rates. IMF-OECD modelling (take your laughter fit now before you resume reading!) suggests certain targets if only these reforms (aka attacking income support systems and undermining job protections etc) are implemented. Actually, this is not a laughing matter.

They want to prioritise “cross-border tax avoidance and evasion” minimisation to provide more cash for governments. Ho-hum!

They want the IMF to be better resourced by national governments. A poor use of public funds.

In all of the 4 pages it is hard to see anything that will generate jobs to reduce the massive gap that persists some 6 years after the GFC appeared.

The Australian Treasurer, who hosted the meeting, boasted later that the G20 finance ministers were “90 per cent of the way towards meeting a 2 per cent target for additional global growth”. The Fairfax article (September 22, 2014) – Hockey hails progress on G20 targets for job growth – outlines the much heralded infrastructure plan that the G20 believe will spur growth.

So not a single public transport, major education, health funding project was announced by any of the nations involved.

Instead, they are going to build a database. The Treasurer claimed:

We have committed to develop a database of infrastructure projects to help match potential investors with projects.

A few IT programmers will be employed as a result.

The IMF’s own submission to the meeting – Growth-Friendly Fiscal Policy – claimed that most advanced nations had “scope to raise tax revenues” but would have to introduce “growth-friendly tax policies” (increases) to ensure fiscal space was available.

First, the assumption that any currency-issuing government has exhausted its fiscal space when inflation is low and threatening to turn negative and millions of people who want to work are without jobs is a nonsense – and a principle myth that the neo-liberal organisations like the IMF perpetuate to reinforce their position at the centre of the ideological war against generalised prosperity.

Second, they claim that removing VAT exemptions but decreasing rates will be growth-friendly. That would only be true if the total tax withdrawn from purchasing power in the non-government sector was reduced. Which would increase fiscal deficits. If that was their aim then it would be more effective for governments to spend an extra dollar than reduce taxes by an extra dollar.

The IMF is clear though that tax changes have to be made in a revenue-neutral manner, which means that overall there is likely to be no major stimulative impact. The fact is that given the scale of the jobs crisis that persists, fiscal deficits have to be much larger than they currently are. Fiscally-neutral strategies will not generate growth on any scale.

Part of the reduction in taxes goes into increased saving – so the spending stimulus is smaller than the direct impact of additional government spending.

Further, most VAT exemptions are on items that protect the lower income groups with high spending ratios per dollar of income received. It is thus conceivable that placing a tax on these items would reduce spending overall even if the rate overall was lower.

Third, the IMF has statements such as “Empirical evidence shows that the growth dividend of public investment will depend on the investment’s return”. Think about that for a moment.

The way to measure ‘return’ is controversial in itself. A public investment project should not be evaluated on the same basis as a project being implemented by the private sector. The latter considers private costs and returns in profit units, while the former is about providing public service and social net benefits.

A public project thus does not have to ‘earn’ a market rate of return on capital for it to be useful and deliver massive benefits to the community. Conflating public and private investment, a characteristic of the neo-liberal era has seriously undermined the quality and volume of public investment in health, public transport, public eduction and the like around the world.

But even if we ignore that point, it is totally false to claim that growth dividend depends on the investment’s return. The growth dividend is the response of the economy to the spending outlays and the multiplied spending that follows. Even if, say a $100 billion investment project was a complete dud and delivered no services worth considering, it would deliver a massive growth dividend to the economy before it was scrapped. People would get work in the construction phase and their spending would induce others to spend and so on through the multiplier chain.

Society might not value the end product but that is a separate issue.

The IMF also urges governments to engage in competitive bidding for large scale infrastructure projects. Why? Given the government can fund any project more cheaply than the private sector why not use that capacity to build first-class infrastructure?

The answer is that it offends the ideological domination of the elites who want as much public money channelled into private companies while at the same time minimising the public money that gets transferred to the weak and the poor.

The scale of the disaster facing the world at present in economic terms is outlined in the report – G20 labour markets: outlook, key challenges and policy responses – and the analysis appears to be talking about a parallel world to that outlined by the boasting Australian Treasurer and the official Communiqué.

It was a joint report prepared by the ILO, OECD and World Bank for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministerial Meeting Melbourne, Australia, 10-11 September 2014. This meeting preceded the Cairns meeting of Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors.

The Report concluded that:

1. “Large employment gaps remain in most G20 countries” and will “remain substantial in several G20 economies until at least 2018”.

2. “Coinciding with the sizeable jobs gap is a deterioration in job quality in a number of G20 countries”.

3. “Real wages have stagnated across many advanced G20 and even fallen in some. Wage growth has significantly lagged behind labour productivity growth in most G20 countries … Wage and income inequality has continued to widen within many G20 countries …”.

4. “Stronger economic growth is a necessary but not sufficient requirement for strong job creation. Re-igniting economic growth also depends on recovery of demand, and this in turn requires stronger job creation and wage growth.”

5. Employment growth is essential for “for achieving sustainable, equitable and inclusive growth”.

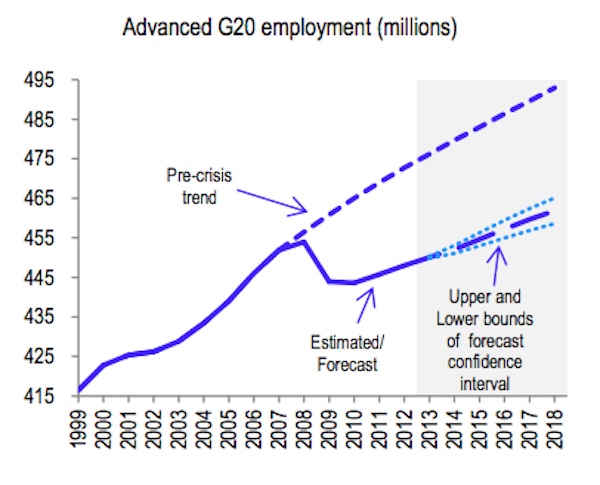

The Report provides this graphic to illustrate how dire the employment gap is for the Advanced G20 nations (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States):

Total employment in the advanced nations as at August 2014 was 455,436 thousand (ignoring quality). The Report estimates that had the economies continued to enjoy trend growth (based on the pre-crisis trend) they would have about 475 million jobs available to their workforces.

So already there is a shortfall of some 20 million jobs give or take. That is huge across 10 nations.

Now be careful when thinking about this. The pre-crisis trend employment growth was, in itself, inadequate in most nations, given the growth of productivity and the labour force. There was substantial mass unemployment and underemployment in many nations at the peak of the last cycle in early 2008 (variously, depending on which nation we are talking about).

But even if the G20 advanced nations lifts their “collective GDP by an additional 1.8 per cent through to 2018”, which is one of the heralded goals outlined in the G20 Communiqué, and this translated into a 1.8 per cent increase in employment (that is, assuming zero productivity growth), then the employment gaps would remain about the same. Do the arithmetic if you do not believe me.

Of course, productivity will not be zero, which means that increasing collective GDP by 1.8 per cent over the next 4 years will not generate a proportionate increase in total employment and as a result the jobs gap will widen further.

That is what the previous graph is really suggesting.

So all the braggadocio of our Federal Treasurer and the IMF boss who has been in Australia the last week, their so-called grand aspirations are ridiculously moribund and reflect their incapacity to design and implement realistic and effective policies.

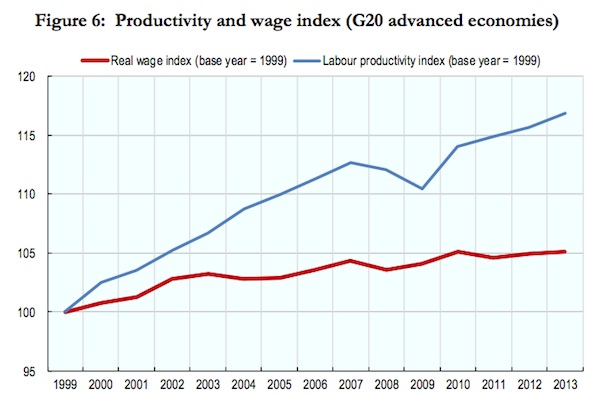

The Joint Report also focuses on the real wage-productivity gap that I have raised previously (often). Please read my blog – The origins of the economic crisis – for more discussion on this point.

The provided this graph and they argue that any real wage gains among the G20 nations:

… was attributable almost entirely to emerging economies, particularly China, while wage growth in advanced economies has been fluctuating around zero since 2008 and been negative in some countries (e.g. Spain).

They implicate the:

… widening gap between growth in wages and labour productivity. In the advanced G20 economies, the gap began before the crisis and has not narrowed since … The gap has grown wider since 2010, as wages in many advanced economies continue to stagnate while productivity has recovered in the group as a whole. For many of the advanced economies, the moderation in wage growth was greater than that which would have been predicted by the relationship between rising unemployment and changes in wage growth observed prior to the crisis.

In fact, the gap in most nations is much larger than implied by this graph. The lines are index numbers and the base year is 1999 = 100. So the graph shows the deviation since that year.

However, the gap started opening up in the 1980s in most countries as the neo-liberal policy onslaught against workers and their unions began in earnest.

In Australia, for example, if we set the base year at 1980, the real wage line would hit around 120 in 2013 and the labour productivity line would be around 180.

The gap reflects a shift in national income to profits (mostly corporate) and given the investment ratio has fallen in most nations, the real income that was redistributed has mostly either been hoarded or gone into financial market speculation and CEO wages.

The widening gap is a major incidental cause of the GFC because it gave the financial markets the gambling chips (redistributed real income from the workers) and reduced the capacity of workers to fund consumption growth out of real wages growth – the historical norm.

In other words, the workers were induced into the credit binge that was funded by the very income that was taken off them and redistributed back to profits.

A neat neo-liberal double play that has wrought massive damage to the world economies.

This has also been implicated into the expanding income inequality in most nations over the last 30 years, which also undermines economic growth.

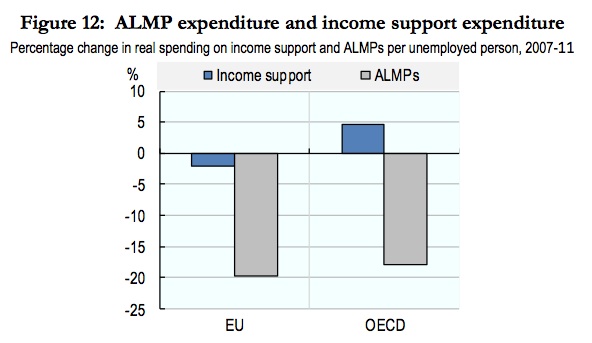

In terms of the G20 policy response to this crisis, the Joint Report says that not only have workers in advanced nations been deprived of “unemployment benefits or received them only for a short period of time” despite losing their jobs in the crisis, the “expenditure on active labour market programmes (ALMPs) failed to keep pace with the rise in unemployment in many countries following the start of the crisis”.

In the EU, for example, both income support and labour market program expenditure fell between 2007 and 2011. This graph is telling:

What is the reason for the employment gap? The Joint Report is clear:

… the current deficit of aggregate demand at the global level, which many economists consider a major factor in explaining the weak and uneven recovery and slow overall growth. The substantial jobs gap and persistent weakness in job quality, wages and incomes are among the factors contributing to the shortfall of aggregate demand via their negative impact on aggregate consumption, investment and government revenue and expenditure.

Which means in plain and simple terms that if the non-government sector will not significantly increase its expenditure then the government sector has to step in and fill the breach.

That means in even more simpler terms – fiscal deficits have to rise.

Trying to steer around this conclusion and invoking all sorts of growth-friendly hype when there is no intention to significantly increase fiscal deficits demonstrates wholesale and deliberate fraud.

The problem though in this Report is the ILO, previously a progressive force, has joined forces with the OECD and the World Bank, which are parts of the neo-liberal propaganda machine and so the conclusion in the Joint Report is weak.

It skates around the need for large deficits by invoking nonsense about fiscal space and the need for public debt consolidation.

Which means about the only people who will benefit in employment terms from such analysis and publications are the bureaucrats who compiled them

Conclusion

The G20 structure is part of the problem and given its current ideological outlook will never be anything but.

It is just an excuse for well-paid officials, most of whom are being supported by the public purse, to swan around the world, wine and dine in opulent hotel and resorts, talk a bit, and do virtually nothing that delivers any benefits to people at large.

Like the IMF and the OECD, the whole institutional structure of the G20 should be abolished.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2014 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Just astonishing levels of GroupThink. Orwell would’ve been proud.

Bill,

This blog is a masterpiece…I wish you would submit it to a newspaper, say Guardian UK or NYT, or a popular magazine, like The Nation. This story really needs to get out to the public.

Again – I disagree with Bill.

Its not a unemployment crisis – its a lack of real purchasing power crisis.

Wage growth or people entering employment would just feed into prices which will cause a even bigger crisis to happen within the production , distribution and consumption system.

We really need to slow down and enjoy life – not to work in the satanic mill which in Ireland means negative wage growth forever.

The crisis is a simple result of the concentration of capital.

Ireland is the most dramatic example of this – with its surging GDP and imploding society.

Watch the ding dong between these clowns on the Irish economy blog to understand the structure of the modern irish economy.

Its quite eduacational but in a inverse fashion.

John the Optimist (GDP fettish) vs Michael Hennigan (export and competitiveness fettish)

“The National Competitiveness Council, a public quango, would be much more muted with claims on competitiveness claims.

If you believe this: [Unit labour costs: “a 21% relative improvement forecast against the Eurozone average”] Prof Patrick Honohan would include among “superficial analysts.”

The average hourly labour cost covering all sectors of the economy other than ‘Agriculture, forestry and fishing’ was €25.03 in the first quarter (Q1) of 2008 and €24.89 in Q2 2014 and there was no relative productivity miracle.

“Ireland was the only country in the EU to experience a decrease in inflation between 2008 and 2012 but prices remain high by EU standards” – – CSO, Jan 2014

In 2013 Irish prices for consumer goods and services were 18% above the European Union (EU) average and fifth highest in the EU28 – – Eurostat, June 2014″

Dork :

In the current structure of extremely concentrated capital ownership the only way the average or median person can increase their purchasing power is via increased wages.

However this also increases prices of goods and services and if these goods and services become unaffordable well…………anybody can figure it out really.

The production distribution and consumption system breaks down.

In the past this absurdity was overcome via pointless economic expansion.

Under the state capitalism of Ireland for example the state helped corporates to export surplus beef to Iraq or something via various state guarantees.

But this GDP /export expansion can no longer continue in Ireland without the enforced starvation of millions (think of Ireland between the 1820s banking crisis and 1840s famine stage )

The social credit position would indeed advocate a reduction of wages (say 25%) but would also give each person a equal share of the countries capital

Problem solved.

The type of goods produced would radically change of course.

21% ~ of Irish oil consumption is currently jet kerosene alone.

That would end pronto.

Ryanair and other corporates dependent on fuel waste would find themselves out of businesss as the back and forth nature of the current Brownian motion economy would be no more.

Who would work for a corporate which uses labour as a livestock anyhow.

People would have a choice as they would already have access to purchasing power without labour.

No need for corrupt unions either

All of these non problems (created by the corporate state) would be solved very quickly

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the blogging every day.

I feel a bit confused by this sentence:

“In other words, the workers were induced into the credit binge that was funded by the very income that was taken off them and redistributed back to profits.”

Isn’t it the different way around? The credit funding the profits?