Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – November 30, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The distinction between structural and the cyclical components of the final government balance helps us to determine the direction of the discretionary fiscal policy stance of the government. In that context, which of the following situations represents the more expansionary outcome:

(a) A budget deficit equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP.

(b) A budget deficit equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP.

(c) You cannot tell because you do not know the decomposition between the cyclical and structural components.

The answer is Option (a).

The trap, if there is one, is in the distinction between the “discretionary” stance and the actual impact of the government balance.

The question probes an understanding of the forces (components) that drive the budget balance that is reported by government agencies at various points in time and how to correctly interpret a budget balance.

In outright terms, a budget deficit that is equivalent to 5 per cent of GDP is more expansionary than a budget deficit outcome that is equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP irrespective of the cyclical and structural components.

In that sense, the question lured you into thinking that only the discretionary component (the actual policy settings) were of interest. In that context, Option (c) would have been the correct answer.

To see the why Option (a) is the best answer we have to explore the issue of decomposing the observed budget balance into the discretionary (now called structural) and cyclical components. The latter component is driven by the automatic stabilisers that are in-built into the budget process.

The federal (or national) government budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit or the deficit increases as a proportion of GDP doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life.

As I explain in the blogs cited below, the measurement issues have a long history and current techniques and frameworks based on the concept of the Non-

Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) bias the resulting analysis such that actual discretionary positions which are contractionary are seen as being less so and expansionary positions are seen as being more expansionary.

The result is that modern depictions of the structural deficit systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So the data provided by the question unambiguously points to Option (a) being the more expansionary impact – made up of a discretionary (structural) deficit of 2 per cent and a cyclical impact of 3 per cent. The cyclical impact is still expansionary – lower tax revenue and higher welfare payments.

Option (b) might in fact signal a higher structural deficit which would indicate a more expansionary fiscal intent from government but it could also indicate a large automatic stabiliser (cyclical) component.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 2:

If private domestic investment is greater than private domestic saving and the current account is in deficit then the government balance has to be in deficit at all levels of GDP.

The answer is False.

This question requires an understanding of the sectoral balances that can be derived from the National Accounts. But it also requires some understanding of the behavioural relationships within and between these sectors which generate the outcomes that are captured in the National Accounts and summarised by the sectoral balances.

We know that from an accounting sense, if the external sector overall is in deficit, then it is impossible for both the private domestic sector and government sector to run surpluses. One of those two has to also be in deficit to satisfy the accounting rules.

The important point is to understand what behaviour and economic adjustments drive these outcomes.

The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

So what about the situation posed in the question?

If the external sector is in deficit then it is draining aggregate demand. That is, spending flows out of the local economy are greater than spending flows coming into the economy from the foreign sector.

If private domestic investment is greater than private domestic saving, then the private domestic sector is running a deficit overall – that is, they are spending more than they are earning.

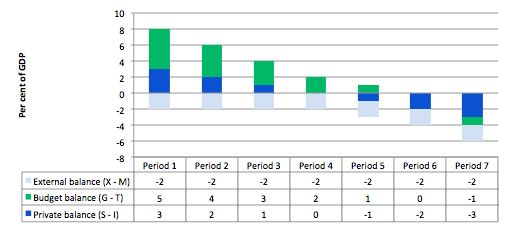

The following graph shows the sectoral balances for seven periods based on different outcomes for the private balance (as a per cent of GDP) and a constant external deficit (to keep things simple).

You can see that in Periods 1 to 3, the private sector is in surplus while the external sector is in deficit. The budget (G – T) is in deficit in each of those periods. The budget only goes into surplus (with a 2 per cent of GDP external deficit) when the injection into aggregate demand from the private domestic sector is greater than the spending drain from the external sector (Period 7).

The reasoning is as follows. If the private domestic sector (households and firms) is saving overall it means that some of the income being produced is not be re-spent. So the private domestic surplus represents a drain on aggregate demand. The external sector is also leaking expenditure. At the current GDP level, if the government didn’t fill the spending gap resulting from the other sectors, then inventories would start to increase beyond the desired level of the firms.

The firms would react to the increased inventory holding costs and would cut back production. How quickly this downturn occurs would depend on a number of factors including the pace and magnitude of the initial demand contraction. But the result would be that the economy would contract – output, employment and income would all fall.

The initial contraction in consumption would multiply through the expenditure system as laid-off workers lose income and cut back on their spending. This would lead to further contractions.

Declining national income (GDP) leads to a number of consequences. Net exports improve as imports fall (less income) but the question clearly assumes that the external sector remains in deficit. Total saving actually starts to decline as income falls as does induced consumption.

The decline in income then stifles firms’ investment plans – they become pessimistic of the chances of realising the output derived from augmented capacity and so aggregate demand plunges further. Both these effects push the private domestic balance further into surplus

With the economy in decline, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise which push the public budget balance towards and eventually into deficit via the automatic stabilisers.

So with an external deficit and a private domestic deficit, it depends on the relative magnitudes of each whether the public budget is in surplus or deficit.

If the injection from the private domestic deficit exceeds the drain from the external sector, then the budget can be surplus. Of-course, this growth strategy cannot be sustainable because it relies on the private domestic sector accumulating increasing level of debt, which is a finite process. Eventually, the private domestic sector debt levels will place it in a precarious solvency state and it will seek to save overall.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 3:

If the ECB uses “overt monetary financing” (OMF) to support the net public spending within the Eurozone, it would still require debt issuance if they wanted to target a non-zero policy interest rate.

The answer is False.

Treaty legalities aside, the ECB could easily support all the member-state deficits by sanctioning the crediting of appropriate bank accounts. The purchasing power would come from “nowhere” – key strokes on a computer system.

This would add to the bank reserves and, other things unchanged, would put downward pressure on the interbank lending rate with a limit of zero if nothing else happened. In that regard, the ECB would not be able to achieve a non-zero interest rate for policy purposes.

But they can simultaneously offer the reserve account holders (the commercial banks) a return on the excess reserves (a support rate) or an equivalent facility which would provide an incentive for the banks to hold the excess reserves without commercial penalty.

So what is the explanation?

The central bank conducts what are called liquidity management operations for two reasons. First, it has to ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. Second, it must maintain aggregate bank reserves at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on “excess” reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Commercial banks maintain accounts with the central bank which permit reserves to be managed and also the clearing system to operate smoothly. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also can set a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank (which might be zero).

Many countries (such as Australia, Canada and zones such as the European Monetary Union) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like Japan and the US have typically not offered a return on reserves until the onset of the current crisis.

If the support rate is zero then persistent excess liquidity in the cash system (excess reserves) will instigate dynamic forces which would drive the short-term interest rate to zero unless the government sells bonds (or raises taxes). This support rate becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy.

The short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

In most nations, commercial banks by law have to maintain positive reserve balances at the central bank, accumulated over some specified period. At the end of each day commercial banks have to appraise the status of their reserve accounts. Those that are in deficit can borrow the required funds from the central bank at the discount rate.

Alternatively banks with excess reserves are faced with earning the support rate which is below the current market rate of interest on overnight funds if they do nothing. Clearly it is profitable for banks with excess funds to lend to banks with deficits at market rates. Competition between banks with excess reserves for custom puts downward pressure on the short-term interest rate (overnight funds rate) and depending on the state of overall liquidity may drive the interbank rate down below the operational target interest rate. When the system is in surplus overall this competition would drive the rate down to the support rate.

The main instrument of this liquidity management is through open market operations, that is, buying and selling government debt. When the competitive pressures in the overnight funds market drives the interbank rate below the desired target rate, the central bank drains liquidity by selling government debt. This open market intervention therefore will result in a higher value for the overnight rate. Importantly, we characterise the debt-issuance as a monetary policy operation designed to provide interest-rate maintenance. This is in stark contrast to orthodox theory which asserts that debt-issuance is an aspect of fiscal policy and is required to finance deficit spending.

Tåhe fundamental principles that arise in a fiat monetary system are as follows.

- The central bank sets the short-term interest rate based on its policy aspirations.

- Government spending is independent of borrowing which the latter best thought of as coming after spending.

- Government spending provides the net financial assets (bank reserves) which ultimately represent the funds used by the non-government agents to purchase the debt.

- Budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates contrary to the myths that appear in macroeconomic textbooks about ‘crowding out’.

- The “penalty for not borrowing” is that the interest rate will fall to the bottom of the “corridor” prevailing in the country which may be zero if the central bank does not offer a return on reserves.

- Government debt-issuance is a “monetary policy” operation rather than being intrinsic to fiscal policy, although in a modern monetary paradigm the distinctions between monetary and fiscal policy as traditionally defined are moot.

Accordingly, debt is issued as an interest-maintenance strategy by the central bank. It has no correspondence with any need to fund government spending. Debt might also be issued if the government wants the private sector to have less purchasing power.

Further, the idea that governments would simply get the central bank to “monetise” treasury debt (which is seen orthodox economists as the alternative “financing” method for government spending) is highly misleading. Debt monetisation is usually referred to as a process whereby the central bank buys government bonds directly from the treasury.

In other words, the federal government borrows money from the central bank rather than the public. Debt monetisation is the process usually implied when a government is said to be printing money. Debt monetisation, all else equal, is said to increase the money supply and can lead to severe inflation.

However, as long as the central bank has a mandate to maintain a target short-term interest rate, the size of its purchases and sales of government debt are not discretionary. Once the central bank sets a short-term interest rate target, its portfolio of government securities changes only because of the transactions that are required to support the target interest rate.

The central bank’s lack of control over the quantity of reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetisation. The central bank is unable to monetise the federal debt by purchasing government securities at will because to do so would cause the short-term target rate to fall to zero or to the support rate. If the central bank purchased securities directly from the treasury and the treasury then spent the money, its expenditures would be excess reserves in the banking system. The central bank would be forced to sell an equal amount of securities to support the target interest rate.

The central bank would act only as an intermediary. The central bank would be buying securities from the treasury and selling them to the public. No monetisation would occur.

However, the central bank may agree to pay the short-term interest rate to banks who hold excess overnight reserves. This would eliminate the need by the commercial banks to access the interbank market to get rid of any excess reserves and would allow the central bank to maintain its target interest rate without issuing debt.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- The consolidated government – treasury and central bank

- Saturday Quiz – May 1, 2010 – answers and discussion

- Understanding central bank operations

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

This Post Has 0 Comments