I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

A bad day for informed debate in Australia

The title gives the game away – Hope all that’s left as growth slows to crawl. It was written by Ross Gittins, the Sydney Morning Herald’s economics editor. Hope is all we have because this thing we call the economy is beyond us and not something we can control. That is the mainstream conceptualisation of the economy as some sort of deity which we just have to offer our sacrifices to and hope for the best. Australia is weathering a renewed burst of deficit terrorism. The media is running stories every day at present about the need to make massive cuts to federal spending and how taxes have to rise to “repair” the budget. The way the issue is being framed by the media is asinine in the extreme. Worse is the fact that the media is refusing to offer a balance to the issue. There is no debate. Mindless TV presenters and journalists are just pumping out “press releases” from partisan think-tanks without the slightest reflection about whether the underlying assumptions are correct. A bad day for informed debate.

Gittins wrote:

Australia and the world are experiencing a Micawber moment. The economic prospects aren’t reassuring, but there’s not a lot we can do except hope something will turn up. Wherever you turn, the outlook is for continuing sub-par growth.

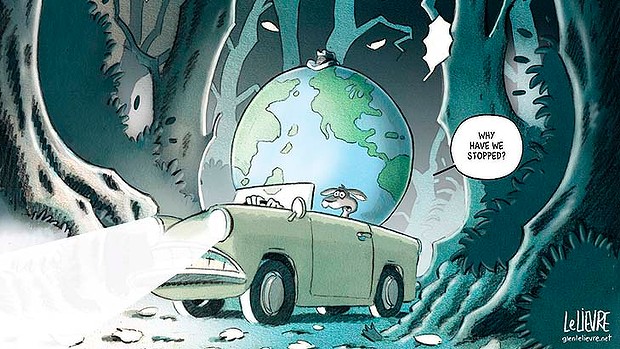

The following cartoon that accompanied the story frames the people (us) as hapless rabbits taking the medicine without any inkling to what is going on.

I have just finished a paper with Louisa Connors titled – Framing Modern Monetary Theory – which we will present at next week’s – 14th Path to Full Employment Conference/19th National Unemployment Conference. This is the (mostly) annual conference that my research centre hosts in Newcastle (this year – December 4-5, 2013).

In that paper, we consider two models of the economy. We use two diagrams that come from the book by Anat Shenker-Osorio – Don’t Buy It – which justaposes these two models.

[Reference: Shenker-Osorio, A. (2012) Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense about the Economy, PublicAffairs, New York]

The first conception we consider is the conservative view, where the basic assumption is according to Shenker-Osorio “people and nature exist primarily to serve the economy”.

This narrative tells us that a competitive, self-regulating economy will deliver maximum wealth and income if allowed to operate with minimum intervention. The economy is figured as a deity that is removed from us though it recognises our endeavours and rewards us accordingly.

We are required to have faith (confidence), work hard and make the necessary sacrifices for the good of the “economy”: those who do not are rightfully deprived of such rewards.

The economy is also figured as a living entity. If the government intervenes in the competitive process and provides an avenue where the undeserving (lazy, etc) can receive rewards then the system becomes ‘sick’.

The solution is to restore the economy’s natural processes (its health), which entails the elimination of government intervention such as minimum wages, job protection, and income support.

The key messages are “self-governing and natural”, which force the obvious conclusion that “government ‘intrusion’ does more harm than good, and we just have to accept current economic hardship”.

Although subscribers to this view would have us believe this is a rational narrative, in fact it represents a type of ‘magical thinking’ more appropriately associated with medieval views on the relationship between individuals and the world.

The orthodox narrative teaches us that our own outcomes are dislocated from the success of the system and so success and failure are both represented as due primarily to our own efforts.

The extent to which private wealth can be seen as linked to socioeconomic status and stable, high quality infrastructure is minimised. Similarly, the unemployed are seen as being responsible for their jobless status, when in reality a systemic shortage of jobs explains their plight.

This narrative is so powerful that progressive politicians and commentators have become seduced into offering ‘fairer’ alternatives to the mainstream solutions rather than challenging mainstream assumptions root-and-branch.

For example, progressives timidly advocate more gradual fiscal austerity when they should be comprehensively rejecting it on the basis of evidence that it fails, and advocating larger deficits to solve the massive rates of labour underutilisation that burden most economies.

Progressives and conservatives are hostage to the same erroneous beliefs about the way the economy operates, yet the public is compelled to believe there is no alternative (TINA) to the damaging economic policies being introduced.

This is the line that the tenor of Gittin’s article and the accompanying cartoon represents.

In Charles Dicken’s book, David Copperfield., Mr Wilkins Micawber, is characterised by his belief that no matter how bad things get “something will turn up”.

The reference by Gittins to Mr Micawber is that our slowing growth and rising unemployment is beyond our control and we just have to hope that something will happen that will change the economic trajectory – he suggests that our best hope is for a depreciation in the Australian dollar.

The article promotes the latest IMF World Economic Outlook assessment and he chooses to quote an IMF official as saying that “most countries”:

… rich and poor – have little ‘space;’ left for further fiscal or monetary stimulus.

He notes that the IMF is seeing the hope not in terms of reversing the cycle with traditional expansionary policy measures (such as, increase the government deficit), but rather in “structural” terms – “strong plans with concrete measures for medium-term fiscal adjustment and entitlement reform” – not much new there.

The IMF have learned very little from the crisis that they helped to cause and which they helped to make worse.

Gittins claims that structural approaches take time to work – although the type of structural reforms proposed by the IMF will “work” where we take that to mean impoverishing more people, entrenching high unemployment and underemployment and undermining the working conditions and job security for workers.

That doesn’t sound like a very impressive path to prosperity.

He thinks that:

In theory, we do retain ‘space’ to further stimulate demand with either lower interest rates or increased government spending … As for the budget, it has been in deficit for four years already, so no one is keen to go any deeper.

It is not just a matter of theory. A currency-issuing government has no financial constraints and can never run out of money.

Fiscal space is thus more accurately defined as the available real goods and services available for sale in the currency of issue.

These are the “means” available to government to fulfil its socio-economic charter. The currency-issuing government can always purchase whatever is for sale in its own currency.

This is also related to the intergenerational (ageing) population claims that pension and health care systems will be unsustainable in the future.

There are no financial constraints on a currency-issuing government providing first-class health care and/or pensions in the future.

The challenge of rising dependency ratios will be whether productivity growth ensures there are adequate real goods and services available to maintain growth in living standards with fewer workers available. These are not financial constraints.

A variation on this proposition is that public debt imposes intergenerational burdens when past budget deficits have to be paid back. Deficits are not “paid back” and intergenerational burdens are linked to the availability of real resources. For example, a generation that exhausts a non-renewable resource imposes a burden on the next generation.

Implications:

- Fiscal space is not defined in terms of some given financial ratios (such as a public debt ratio).

- Fiscal space refers to the extent of the available real resources that the government is able to utilise in pursuit of its socio-economic program.

In terms of framing, we should always be cogniscant of the national accounting reality that the government deficit always equals the non-government surplus, and the government surplus always equals the non-government deficit.

For most nations, the combination of external deficits and a desire by the private domestic sector to save overall, means that the non-government sector will act as a drain on overall spending in relation to income flows.

This means a continuous budget deficit is required to sustain a given level of activity.

A progressive macroeconomics agenda has to recognise that a normal state will require continuous government deficits over each business cycle rising and falling with fluctuations in non-government sector net spending. Rarely, will a government surplus be appropriate.

Further, government deficits are not just appropriate in times of recession or slow growth. They are required whenever there is a non-government desire for a surplus, which is the typical case.

In terms of a progressive frame to counter the neo-liberal obsession that there is not enough space, we might continually reinforce the frame:

Government deficits are normal, surpluses are atypical

This means that ‘balanced budgets over the cycle’ type arguments, which progressives use in order to appear responsible – ‘deficits in bad times, surpluses later when times are better’ – are destructive and fall into the misleading ‘deficits are bad’ frame.

Progressives would thus frame the concept of fiscal space in terms of the idle real resources that can be brought into productive use via higher government spending and/or lower taxation. The idle resources signal that the government deficit is too low or the surplus is too large. The desired destination is zero waste and the required action is a larger deficit.

The claim by Gittins that we just have to “hope something turns up” is thus a passive neo-liberal representation of our options, which are in denial of the obvious alternative.

The alternative view of the economy we outline in the paper noted above is where the economy works for us as our construction and people are organically embedded and nurtured by the natural environment.

Shenkar-Osorio says

… we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, not how much it will increase the size of the economy.

In this view, the economy is seen as a constructed object and policy interventions should be appraised in terms of how functional they are in relation to our broad goals, which a progressive vision would articulate in terms of advancing public well-being and maximising the potential for all citizens with the limits of environmental sustainability.

The focus shifts to one of placing our human goals at the centre of our thinking about the economy.

This perspective echoes the principles of functional finance outlined by Abba Lerner in his 1943 article.

[Reference: Lerner, A. (1943) ‘Functional Finance and the Federal Debt’, Social Research, 10(1), 38-51]

Consistent with this, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) highlights the irrelevance of a narrow focus on the budget balance without reference to a broader human context.

In this narrative, people create the economy. There is nothing natural about it. Concepts such as the ‘natural rate of unemployment, which imply that it should be left to its own equilibrating forces to reach its natural state are erroneous.

Governments can always choose and sustain a particular unemployment rate.

We create government as our agent to do things that we cannot easily do ourselves and we understand that the economy will only serve our common purposes if it is subjected to active oversight and control.

The two visions of the economy can be summarised in value terms as individualistic (neo-liberal) and collectivist (alternative).

For a progressive, collective will is important because it provides the political justification for more equally sharing the costs and benefits of economic activity.

Progressives have historically argued that government has an obligation to create work if the private market fails to create enough employment.

Accordingly, collective will means that our government is empowered to use net spending (deficits) to ensure there are enough jobs available for all those who want to work.

In other words, it is not just about “hoping something turns up”. We should demand our governments use the policies available, which work in known ways, to improve our circumstances.

I was already depressed and then I saw the headline last night (see graphic) and thought (not!) that the Grattan Institute, which has joined the queue of neo-liberal think tanks (not that they do much thinking), might have had a bit of an epiphany.

After all “boost” means to increase and the deficit certainly needs to increase right now given the sluggish real GDP growth and the rising unemployment.

In April 2013, I wrote a blog – The day the Australian media failed the public, again – which considered the appalling coverage the Australian media had dealt with the lead up to the May federal budget deliberations.

The so-called big deal at the time was that the then federal government had revised their estimates of the 2012-13 budget deficit upwards after downgrading growth estimates.

It also followed the Treasurer’s announcement that they would not be able to achieve a surplus in this year as planned. The media seemed to have thought that the earlier pursuit of the surplus at a time when non-government sector spending growth was modest at best and the the economy was only growing on the back of the 2008-09 fiscal stimulus was actually responsible policy.

They seemed to be “surprised” that the surplus would not be achieved and forecasters quickly were revising their estimates to higher deficits after failing dramatically to see why the initial promise of a surplus by 2013-14 was the stuff of angels dancing on pinheads.

The reality was that the government was never going to remotely achieve a surplus given the fundamentals in the economy and the pursuit of it was extremely damaging for growth. The rising unemployment and flat employment growth over the last two years is the result of that highly irresponsible fiscal stance.

In that blog, I also considered a “report” from the Grattan Institute that claimed that Australia is facing a “decade of massive budget deficits if state and federal governments don’t rein in spending, and increase taxes”. They claim that “by 2023 the combined annual deficit of state and federal governments could balloon to $60 billion”.

I did some elementary arithmetic and it showed that if GDP grows by 3 per cent per annum on average over the next decade (which is under the government forecasts and below trend) then a $A60 billion deficit will be about 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2023.

In relative terms that is not what I would call “massive”. But then it makes no sense to conclude anything about that figure unless we know what it is supporting in real terms and what the spending and saving desires (and actions) of the non-government sector (external and private domestic) are.

The Grattan Report was so bad that if it had been presented by a first-year macroeconomics students I would have failed it and advised the person to pursue another career.

Well, obviously suffering from attention deprivation, the Grattan Institute is back with another (recycled) report which once again the mainstream media is salivating over. The director has been on morning TV and radio this morning repeating his moronic analysis – “we have to repair this deficit now” sort of drivel.

No critical reviews, no hard questions like “why is the deficit a problem?”. It is just assumed to be a problem by the journalists.

And Gittins was back to it this morning as well. His column today with an uncritical promotion for a recycled “report” from the Grattan Institute.

The article – Will Abbott be deficient on deficits? – was accompanied by the following cartoon appeared – a Tree Metaphor – with an axe to cut it down.

There was no balance in this article. Why wasn’t the tree constructed as a beautiful growing thing mirroring what happens to non-government net financial assets when the government is running a deficit?

That would be too much to ask. The Fairfax press now has a banner head under their daily papers (Sydney Morning Herald, Melbourne Age) – Independent. Always – which is just an attempt to separate themselves from the openly neo-liberal slime presented by Rupert Murdoch’s News Limited publications.

The problem is that Fairfax continually act as vehicles for the same slime. They might be more muted in their headlines and a little more subtle in the narratives but Independent they are not.

Gittins claims that the Grattan Report teaches us that:

We can’t grow our way out of this deficit. Being ‘structural’, it already assumes the economy is back to growing normally … With one exception, the only way a structural deficit can be reduced is to make explicit decisions to cut spending or increase taxes.

This could have been a first-year examination question. Gittins would fail as would the Grattan Institute researchers.

Think about it for a second. On its own logic, if the economy is growing normally then the fiscal settings must be correct.

The idea that a “structural” deficit is bad per se is nonsensical. Budget deficits are neither good nor bad and, in accounting terms, equal the non-government surplus.

In behavioural terms, they are required when spending intentions of the non-government sector are insufficient to ensure full utilisation of available productive resources. The context matters because the budget is a vehicle to achieving socio-economic goals rather than an end in itself.

The progressive starting point has to be the social purpose of government policy rather than a view of the economy to be a natural entity, separated from us, which gets sick if government attempts to alter its natural course.

But the important point is that the notion that the Australian economy is “back to growing normally” defies the data. The real GDP growth rate is well below even conservative estimates of trend and unemployment is well above the last low (February 2008).

Further, underemployment is rising and taken together there are more than 13 per cent of willing workers not able to work (at all or enough hours).

So the structural deficit is too low not too large. And a deficit of around 4 per cent of GDP is probably indicated.

The problem with the public debate is that the media which frames it refuses to seek balance in their stories.

The journalists are driven by headlines rather than presenting information.

Conclusion

I have a long flight coming up. So …

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Lucy Turnbull, wife of Malcolm Turnbull is on the board at the Grattan Institute. That’s good enough for me.

Bill,

You keep complaining about what appears in the press, but what efforts have leading MMTers like you or Stephanie Kelton made to get articles in the Financial Times or Wall Street Journal, etc?

Warren Mosler regularly gets articles in Huffington. If you got an article in the FT or WSJ, the readership would be far larger than this blog, wouldn’t it?

I suspect what you’re not too good at is packing the relevant information into the 700 to 800 words required by newspapers for Op-eds. Chis Dillow criticised you (and Frances Coppola) for being too verbose recently. My brain works differently to yours: while I’m thick as two planks in most ways, I’m good at cutting arguments down to the minimum number of words. So I’d be happy to act as an article writer for the MMT community, with others (e.g. you) acting as author when it comes to actually submitting articles to the FT or whatever.

You highlight the word STRUCTURAL, which is apt because in many respects it is the most important element in your long-running campaign to make monetary economics more understandable to the ordinary person in the street.

Being mere ordinary folk we are mentally disposed to think in terms of achieving balanced budgets at worst, and preferably to achieving a surplus. To the extent that we can embrace government deficits we have an inclination to view any government distribution as spendthrift and politically motivated ( in its derogatory sense). This is hardly surprising when generations of news articles have painted government expenditure as a poor example of what to do with confiscated funds. Your obvious exasperation at this naivety coupled with a sympathetic remedy to the plight of the unemployed merely ratchets up any hesitancy to embrace JG.

Whether or not you call such a jaundiced view of the economy as a harsh fact of life, there is a common reluctance to install a safety net that becomes all-embracing. The fact that we may still be a long way from reaching that sublime existence does not detract from a profound fear about where this economic journey will lead us. The Western world has enjoyed a prolonged period of progress but it has been accompanied by setbacks that vary between mild recessions and financial upheavals to outright wars and human catastrophy. Even today in the English version of the FT there is reference to trends in job markets that show in the US since the year 2000 computer related jobs have fallen by over 100,000, jobs in telecoms have dropped by 576,000 even though revenue and margins may be on the rise. Automation has also affected telemarketing (44% fall), electrical engineers (37% fall) and desktop publishers (39% fall).

If the general public are to fall in behind the concept of JG it will be necessary for them to embrace not only the grim news that the media use to frighten and intimidate but also the uplifting news that a future is unfolding that ordinary people can embrace enthusiastically. That must show that our wants and desires are far from satisfied, that there are the resources available to meet these needs and we have the wherewithal to meet the STRUCTURAL changes in the employment market that are necessary.

Good post, as always!

Let me add that I like to say it this way.

The purpose of taxation is to create unemployment as defined: people looking for paid work.

Govt does this to provision itself.

It taxes in something no one has- the $A- which creates sellers of real goods and services (unemployment) presumably so the govt. can then hire them to provision itself.

So what’s the point of creating more unemployed than the govt wants to hire? Or, said another way, what’s the point of creating the unemployed govt wants to hire and then not hiring them?

There is no point, of course, and wouldn’t be under by anyone who understood how it works.

Furthermore, the $A is a simple ‘tax credit’ as its only ultimate use is to pay taxes.

That is, when the govt spend a $A, that dollar is either

1. used to pay taxes and is lost to the economy, or

2. is not immediately used to pay taxes and remains outstanding until it is used.

The govt. allows those unused tax credits to be held in three forms- as actual cash, as cash balances at the reserve bank, or as balances in securities accounts at the reserve bank called Treasury securities.

The total of the three is the national debt.

The national debt is simply the total tax credits spent but not yet used to pay taxes.

And so the question of ‘how is it going to be paid back’ is entirely inapplicable!

So why does the economy need a deficit (tax credits spent and not yet used to pay taxes)?

Exactly as Bill says- to accommodate the desire to net save.

bottom line- unemployment is always and necessarily the evidence that the govt hasn’t spent enough to cover the need to pay taxes and the desire to save.

same thing, other way around- If the tax unemploys more people than the govt hired, it should cut the tax or hire (directly or indirectly) the rest of the unemployed.

Best!

Warren

http://www.moslereconomics.com

twitter @wbmosler

Excellent stuff as always, Bill, and the reason why media reports on economics and finance are almost impossible to read/listen to/watch to the end. I’m very much looking forward to seeing you present this paper next week.

Hi Bill and Warren,

I just note Ralph’s point (2nd comment). I’m not sure he is being totally fair on this. My guess is that much of the MSM , certainly the WSJ , wouldn’t allow articles that challenged their neo-liberal orthodoxy.

Maybe the UK’s Guardian would be more receptive. Maybe not though!

I’d be interested to know your experiences in dealing with the MSM. It would certainly be good if MMT could have a wider audience in the UK and Europe generally.

Peter

Thanks Warren,

We’re not all wired up to process information in the same way so it’s nice to have someone come along and tell the same story using different language. It fills in the little dips and hollows.

And maybe you should visit Australia a bit more often… last time you made the front page of “The Sydney Morning Herald” !

@Warren,

Excellent comment! I wish we could get you on TV more to explain how the economy works. We have some real dimwits currently doing that job here in Australia who I would like to see join the ranks of the unemployed!

Tim Colebatch once again shows that Fairfax people accept the same neo-liberal dope in his “We Simply Can’t have the cake and eat it” piece here: http://www.smh.com.au/comment/we-simply-cant-have-our-cake-and-eat-it-too-20131125-2y5wg.html. Increasing aged pension age: “With our life expectancy increasing by two years every decade, the Productivity Commission suggested that the government think about increasing the pension age after 2023, eventually to 70. It was immediately howled down by a chorus from all sides, as usually sensible people united to denounce the idea that any of our increased lifespan should have to be spent at work.”

All setting the scene. Intelligent people ie Tim and those supporting the idea are dragged down by us nongs who think (KNOW) this is a terrible idea. Softening us up for this to happen as both major parties will go along with it soon enough as we have seen from the recent rise to 67 and the same policies being pushed throughout the western world.

Peter,

The WSJ is obviously biased towards the neo-liberal / Pete Peterson / Rogoff view, but it does publish articles giving opposing views. And the FT is less biased than the WSJ.

In science, the word ‘orthodoxy’ would be almost synonymous with consensus. The idea being that the ‘big bang theory’, Darwinian evolutionary theory, or whatever, would be ‘consensus science’ because it provided the best explanation for observable facts.

It doesn’t seem to work that way in economics though!

It looks like it might be up to the students to teach their lecturers, if this report is anything to go by!

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/oct/24/students-post-crash-economics

Peter,

Fair point although I think it took at least 20 years before Darwin published his paper due to the prevailing orthodoxy. It feels like we’re in the same space at the moment. The facts support MMT but the majority believe something else. I guess I’m hoping that in the modern world paradigm shifts should move much more quickly but, as Bill has regularly pointed out, orthodoxy comes right from the top and is embedded in education, media, politics, culture – and that hasn’t really changed in hundreds of years. However, I think we all have almost a “duty” to try and change the current thinking – I send everyone who’s interested to this blog to find out more. I’m certainly meeting more and more people (UK and US primarily) who are starting to question the economics being said by most politicians so perhaps the shift can happen!

Bill Mitchell (Framing Modern Monetary Theory)

“Proponents of neo-classical macroeconomics have been extremely successful in their

use of common metaphors to advance their ideological interests. What is, in fact, a myth that is designed to advance a narrow ideological interest, is constructed and accepted by the public as a verity. Thus ideology triumphs over evidence and we accept falsehoods as truth. ”

Tim Colebatch:

“We simply can’t have our cake and eat it too”

Yes I agree about the duty to change current thinking. The more the powers-that-be push their neo-liberal theory, which obviously fails the straightforward scientific test of being able to explain observed effects, the more we have to propagate a theory which does. And if it doesn’t, the theory needs to be modified. Its not a question of politics or ideology – its science. Economists do have to start following the established scientific method before the ‘dismal science’ tag can be removed from economics.

Thankfully there some who do, so the position is far from hopeless.

This is my contribution: http://petermartin2001.wordpress.com/