I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

More worn out ideological prattle from R&R

There are seven graphs in the paper. An Excel spreadsheet was involved. Shonky stuff alert! R&R are back with another attention-seeking effort after they were disgraced when their Excel manipulation that just happened to generate ideologically-convenient results was discovered to be shonky (in the extreme). This time is not different though. As in all their so-called historical insights the pair conflate monetary regimes across time and at points of time, which means most of their conclusions are erroneous. While their insolvency threshold has zero credibility now they also still hang on it, if only by implication. And they claim that repression is when residents of free nations enjoy parking their savings in risk-free, interest-bearing government bonds, instead of taking risks with commercial paper. Sounds like free choice to me. Is suggest R&R take some R&R and let governments get on with expanding their deficits and reducing unemployment. The public debt ratios will take care of themselves.

The contention in their latest paper – Financial and Sovereign Debt Crises: Some Lessons Learned and Those Forgotten – is that advanced nations are going to have to face the medicine soon enough, just like poor “emerging economies” because austerity and/or growth will not reduce debt levels.

This is one of those studies that assumes the major issues away because they are inconvenient to the ideology being pushed.

Think about this statement:

Even as the recovery consistently came in far weaker than most forecasters were expecting, policymakers continued to underestimate the depth and duration of the downturn.

Question: Which forecasters were expecting stronger growth? Answer: the IMF, the OECD, the ECB, the politicians that were imposing austerity and hiding that fact that it would kill growth because that would have made it harder to impose.

Question: Why did the recovery come “in far weaker”? Answer: because the governments refused to increase their deficits to the levels necessary to support the saving desires of the non-government sector and hold to that line for long enough while the private balance sheets were adjusting debt levels down.

So the same ideology that entrenched the world in the crisis, forced governments to abandon their countercyclical responsibilities and, instead, impose fiscal austerity. It was obvious that growth would weaken and a double- or triple-dip recession would be the likely.

No-one who understands the way the monetary system operates was expecting strong growth once austerity was imposed despite the lies the multilateral agencies and certain governments were spreading.

These characters claimed the private sector were Ricardian in outlook, which led to the outlandish claims that the private sector – heavily indebted, enduring rising mass unemployment, and facing massive cuts to their pensions, wages, and other conditions of work and life – were so intimidated by the budget deficits (the so-called future tax liability effect) that on the announcement that their government that they would bring the deficits down, these private agents would spend like crazy.

Psychology 101, seemingly is a puzzle to these economists, even more than Macroeconomics 101 is.

Underlying the latest R&R paper is the assertion that public debt levels have to be brought down before there can be a recovery and the only way this can be done is through default (“debt restructuring or conversions”), “financial repression” and inflation.

They use the term “debt overhangs”, which implies their is an edge (threshold) over which debt becomes unsustainable. This is what the scandalous Excel spreadsheet cheating paper alleged, that is, before the formulae were extended to the full sample available and their conclusions were no longer supported.

I agree with them that the European political and economic elites are in a “denial cycle” – where they claim that austerity will solve all their problems. I agree that there is no credible “optimistic medium-term scenario” for Europe based on the current policy mix. Permanent stagnation is more the outlook.

But where the paper is dishonest is that it seeks to generalise what is happening in the Eurozone to other advanced economies.

Further, they claim that:

Nowhere is the denial problem more acute than the collective amnesia on advanced country deleveraging experiences (especially, but not exclusively, before World War II) that involved a variety of sovereign and private restructuring, default, debt conversions and financial repression. This denial has led to policies that in some cases risk exacerbating the ultimate costs of deleveraging.

For most advanced nations the history before 1971 that is recorded is irrelevant to the current situation. Various systems of fixed exchange rates, gold standards and convertibility were in force, which introduced default risk to public debt issuance.

R&R think that “delving deeper into the widespread default by both advanced and emerging European nations on World War I debts to the United States during the 1930s” is instructive for guiding our understanding of the current day.

But since the Bretton Woods system collapsed, when US President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971, those countries that floated and only issued public debt in their own currencies faced zero default risk.

One might just say that the denial problem is that R&R keep:

1. Conflating post 1971 with what went before.

2. Conflating Eurozone where the member states use a foreign currency with nations that use their own currency.

3. Conflating nations that peg their exchange rates and/or issue debt denominated in foreign currencies or provide guarantees to bond holders to insure them against foreign exchange exposure with nations that float, and only issue public debt in their own currencies with no foreign exchange risk insurance.

Once we separate their “historical sample” into groups that have similar monetary arrangements (oranges compared to oranges) their story collapses.

Their principle claim is that there is a massive “debt overhang” and:

In light of this danger, we review the possible options, concluding that the endgame to the global financial crisis is likely to require some combination of financial repression (a non- transparent form of debt restructuring), outright restructuring of public and private debt, conversions, somewhat higher inflation and a variety capital controls under the umbrella of macroprudential regulation.

They also claim “austerity is necessary”.

The paper is thus predicated on the assertion that there is a dangerous debt overhang across the governments of the advanced world and this is unsustainable and austerity, while necessary, will not be enough to bring the debt down.

That is, of-course, just their ideological position.

What is the so-called debt overhang?

They say that “the overall debt problem facing advanced economies today is difficult to overstate”. They then present Figure 2 which shows gross general government debt ratios (% of GDP) rising to record levels and then refer to their Excel spreadsheet paper (and another derivative paper) that apparently “show that periods of high public debt have very often been associated with below trend growth”.

First, they have never showed that without cribbing.

Second, they have never established a credible public debt threshold beyond which growth falters.

Third, faltering growth is not insolvency.

Fourth, and most important, the question of causality has never been resolved in any of their work.

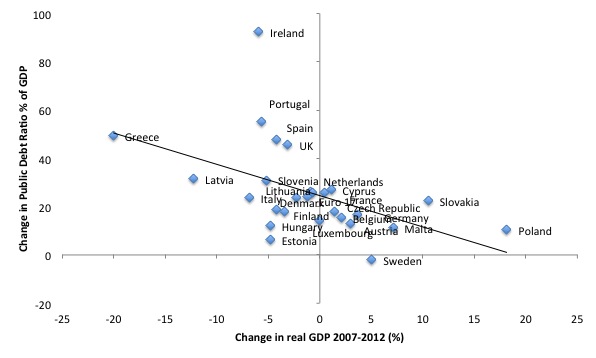

The following graph shows the percentage change in real GDP (volume index) between 2007 and 2012 (horizontal axis) and the same change in the public debt ratio (as a percent of GDP) (vertical axis) for the majority of European nations. The black line is a simple linear trend.

The causality could run either way but the evidence suggests that it runs from real GDP changes to changes in public debt ratios. The furore over the Rogoff and Reinhardt work was not really about their spreadsheet incompetence but the direction of causality. The implication of their 80 per cent threshold for “safe” public debt ratios was that once it went above that ratio, growth suffered.

There is no solid evidence to support that view. To some extent over the period analysed it is moot anyway in trying to understand why the debt ratios grew so much.

Any person will understand that the meltdown in 2008 was not a public debt event. It was a collapse in confidence that led to a spending withdrawal that cause real GDP to decline sharply.

This was followed by the imposition of fiscal austerity in most nations which further dented growth. The rise in the deficits and, under the current institutional arrangements, the rise in debt issuance, saw public debt ratios grow rapidly.

The causality is clear in this case.

They next claim that it is valid to lump private and public external debt together to expose the vulnerability of a nation. Again, denial of reality.

Certainly, a large buildup of external private debt (denominated in foreign currencies) leaves a nation exposed to default risk if net exports are not strong enough. But that has no implications for the solvency risk of a currency-issuing government.

R&R claim that the private debts are really “hidden debts” of the government presumably because they assume the government will always assume responsibility for them if there is a major meltdown.

Whether Governments do operate in a way that allows returns to be privatised and losses to be socialised is one matter. But a sensible government would never agree to assume the responsibility for the foreign currency liabilities of the private sector.

And if they refused to take these liabilities on and perhaps offered some sort of restructuring in their own currency to foreign creditors this says nothing about the solvency status of the government’ own liabilities denominated in its own currency.

Further, a currency-issuing government, does not have to sacrifice domestic policy objectives that may require an increased government deficit when the private sector is forced to default on its liabilities due to incapacity to pay.

They say that:

Domestic debt issued in domestic currency typically offers a far wider range of partial default options than does foreign-currency denominated external debt.

But again the implication is that domestic debt presents some solvency problem for the government. It is quite obvious that foreign-currency denominated public debt is problematic because it involves the government surrendering its unique position as the currency issuer.

No currency-issuing government has to issue such debt.

The unproven starting assumption – that any debt is bad once it gets to a certain level – is just asserted by R&R – and some dodgy research papers proffered as evidence. The self-referential nature of their arguments continues to amuse me.

So Section III “Today’s Multifaceted Debt Overhang” starts on page 7 and concludes on page 12. There is a lot of blowhard about danger, risk, financial repression, inflation, and the rest of the horror stories but very little argument presented to substantiate the title of the section.

All we learn is that public and private debt ratios have risen – yes – and this is an overhang. As noted above, an overhang has to be calibrated in relation to some benchmark. What do these debt ratios overhang?

We never find out. We never are told what the benchmark is. The analysis is thus vacuous bluster.

Section IV is about debt reduction and we learn that there are “essentially five ways to reduce large debt to GDP ratio” but before that discussion should be had, one would have expected a prior argument to define what a “large debt to GDP ratio” is and why any debt to GDP ratio has to be reduced for an advanced nation, which issues its own currency.

That is the elephant that is ignored.

It seems that the journalists are also beguiled the flawed R&R logic. Larry Elliot of the UK Guardian wrote a review of the paper (November 21, 2013) – Reinhart and Rogoff’s latest paper warns on financial repression – which is more or less a press release for the authors.

His willingness to deceive his readers is captured in his conclusion, which I suppose he thought was rather deep, yet pithy:

An old-fashioned default remains the last taboo, although looking at the debt to GDP levels in Japan, Italy or Greece only the bravest would gamble that it will never happen.

A more reasonable assessment is that this closing assessment is unmitigated nonsense.

Japan issues its own currency. Greece and Italy surrendered that capacity when they signed up for the Euro. Anyone who conflates the two cases either doesn’t know what they are talking about or is deliberately choosing to mislead their audience.

There is zero default risk in Japan on its outstanding public debt liabilities.

Conclusion

Another memorable demonstration by R&R of how dangerous they actually are and how audacious they are. A major scandal, which many considered demonstrated research fraud, doesn’t phase them one bit.

But on the quality of research this paper gets 0/10 for quality and 10/10 for its perseverance in perpetuating the worn-out ideological prattle that the mainstream economists think is knowledge.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Rogoff and Reinhart aren’t just dumb: they’re liars into the bargain. Their latest lie (or “grotesque distortion of the truth” if you prefer) is to claim that they never said the 90% debt level was any sort of tipping point.

Dear Bill

You keep hammering, rightly, on the importance of issuing debt in the domestic currency. What if lenders have very little faith in the domestic currency because the government which issues it has a habit of causing inflation. The solution then should be to offer indexed bonds. Each year the redemption value of the bond will be increased by the inflation rate of the previous year. Indexed bonds are a good idea anyway.

No saver is entitled to see his savings grow. After all the food that you store in your fridge doesn’t go up in value either, but it is only fair that savers should not be expropriated through inflation. I know all about the paradox of thrift, but modest saving is prudent. A household that has some savings is better equipped to deal with financial emergencies. The welfare state, by protecting people against sickness, disability, unemployment and old age, of course considerably reduces the household need for savings.

If their is a savings glut because of a very unequal distribution of income, then the solution is to increase the marginal tax rates on higher brackets of income.

Regards. James

“What if lenders have very little faith in the domestic currency because the government which issues it has a habit of causing inflation. ”

How ? I mean seriously – How would the government have a habit of causing inflation and why would lenders lose faith in the domestic currency if it is the only means acceptable by which people can pay their taxes ?

Just come out and compare the current situation with Weimar Germany so we can all have a laugh and move on.

Your conclusion reminded me of Douglas Adams’ Zaphod Beeblebrox

@ James ~

Why offer bonds at all? They are merely a debt swap, and do not increase the fiscal capacity of the government.

Dear Alan

Please don’t react in such a knee-jerk fashion. I wasn’t thinking of Weimar or Zimbabwe, which are exceptional cases, but of Latin America, where double-digit inflation has been a recurrent experience. We may debate about the causes of this, but not about its reality.

As to currency and taxes, I do not except the MMT view that people accept a currency only because they have to pay taxes in it. It is just the other way around. Governments will only raise taxes in a currency which people already accept. Suppose that in Ruritania every able-bodied adult under 65 has to pay a pig tax, that is, every year they owe a pig weighing at least 80 kilos to the government. That makes sense if Ruritanians are big pork eaters. The government can then slaughter the pigs and use pork as a payment for the services and goods that it buys from Ruritanian citizens.

Now suppose that nobody in Ruritania eats pork. Would it then make sense for the government to impose a pig tax? What can it do with pork since nobody will sell anything to the government in return for pork? The Ruritanians would still raise pigs to pay their taxes, but the government would quickly levy a different tax if they were left with useless pork, unless it could use the pork to buy stuff from pork-eating foreigners. Raising taxes is like accepting payment. You only accept payment in a currency that you can use to buy from somebody else. What gives a currency value is the willingness of sellers to accept it as payment.

In WWII, the Japanese introduced a new currency in the Philippines. As the defeat of Japan became more imminent, people became more reluctant to accept this currency as payment out of fear that the currency would become worthless after the Japanese had been driven out. The result was of course inflation.

Regards. James

James,

Most sane people would argure that it is desirable for money to have the following four characteristics:

1) durability,

2) divisibility,

3) transportability, and

4) noncounterfeitability

On those points alone your example of Ruritania and pigs is a complete and utter failure.

“Governments will only raise taxes in a currency which people already accept. ”

How did the Euro happen then? Or the Reichsmark. Or the Real. Why did the Euro pre-cursors stop being used, when an entire continent accepted them previously?

It is fairly obvious from the business card analogy that any institution or individual with power to incarcerate and punish can impose taxation in any token and force the people under the control of that institution or individual to work for that token – on pain of punishment.

That is how it works. Collectively we invest in the government with the power to impose social liabilities on people and punish them for failing to fulfil those liabilities.

It’s when that power wanes via various mechanisms (treaty, wars, revolution, etc), that currencies change.

James,

First, inflation-indexed bonds are a horribad idea, for the same reason any inflation indexing is: In the event of a supply-side shock (think force majeure events like earthquakes and wars), commitment to inflation indexing becomes untenable. It is much more viable to index to nominal GDP (per capita or absolute, depending on the instrument or transfer payment in question).

Second, why do savers have a right to expect to be compensated for inflation? Money savings provide a valuable privilege: The ability to push purchasing power into the future without shouldering any operational risk whatever. In a world of Knightian uncertainty, this privilege has value – as evidenced by the fact that upholding it requires the regular deployment of armed goons. Inflation, in this view, is payment for services rendered in protecting your purchasing power from operational risk.

Third, aside from the logistical issues with using pork as legal tender, there is also the non-trivial fact that the majority of the point of having a legal tender is that the government can make it out of whole cloth. The Ruritanian government in your example cannot pay its officials in pork that does not yet exist. Whereas if it collects taxes in the president’s autographed business cards, then it can pay its officials simply by printing up more business cards.

– Jake

Alan: You are not dealing with my main argument.

Neil: The euro was not fundamentally a new currency. A euro was simply x guilders, y francs, z marks. In any case, people accepted the euro, not only because they needed to pay taxes to the government, but also because everybody in the Eurozone already lived in a thoroughgoing monetized economy. They either had to accept the euro or else revert to barter. The latter being impossible, they embraced the former, however reluctantly. Still, governments in the Eurozone could levy taxes in euros only because people who work for the government or sell to the government were willing to be paid in euros. My point that governments raise taxes only in a currency that people are willing to accept as payment for goods or work sold to the government remains valid.

Jake: If inflation is caused by the monetary policy of the government, then it is not unreasonable to demand that people who have savings with the government be compensated for that. It is the government that is responsible for the inflation, so it should also be responsible for the indexing. In Canada, all government benefits such as Canada Pension, Old Age Security and also the tax brackets are indexed, as I think they should be.

If there is deflation due to a supply shock, then indexing will reduce the redemption value of the bonds. That makes it easier for debtors, not harder. Deflation without indexing can be a nightmare for debtors because the real value of the debt increases. Indexing doesn’t only mean an increase but also a decrease. A negative rate of inflation should mean a decrease in the redemption value of bonds.

“They either had to accept the euro or else revert to barter. ”

Which is precisely why any government stated token will be accepted.

You’re putting the cart before the horse.

People become willing to work for the token because otherwise they go to jail – and that’s because the government has legitimate authority to impose the liability and therefore legitimate authority to change the token as they see fit – as we’ve seen in countless instances.

The business card analogy works. I can get my kids to work for Neil tokens. Victorian miners worked for mine coins, which they needed to pay the rent on their tied cottages. You can get people you have some power over to work for the token they need to settle their liabilities.

And the source of that is the monopoly on force delegated to an authority.

I used to think that Economics had some resemblance to Science, but it does not.

In a fundamental way I can’t understand why Economists seem to think that money is somehow part of the natural world and is not under human control.

Dear Neil

In the past it was not uncommon among Latin American landlords to pay their employees with papelitos (little pieces of paper) These papelitos could be used by the employees to buy various things at the landstore’s store. Elsewhere they were useless. That works because the landlord was in fact a monopsonist to his employees. However, no modern economy is like that. People use currency to pay all sellers within the country. Sellers accept the currency because other sellers accept it. When people in the Eurozone accepted euros, they weren’t just thinking of paying their taxes.

It is true that a modern fiat currency is a government creation, but people accept it because it has many advantages, not just because they are coerced into paying taxes. Suppose that the government of Ruritania owned so much oil that oil profits were sufficient to finance all government activities. Then there would be no taxes at all, but the Ruritanian government could still be the sole issuer and manager of ruris, and Ruritanians would still accept the ruri for their transactions.

To use an analogy, people in Britain don’t just learn English because that is the official language of the UK. They also learn it because most other people in the UK use it for private communication. People in the UK accept English because nearly everybody else in the UK accepts it too. In Ireland, on the other hand, the Irish language is languishing despite its official status because most inhabitants of Ireland speak English. An Irish couple will raise their child in English because they know that other couples are doing the same. There is some similarity between a currency and a language because both are used in dealing with other people.

Regards. James

” When people in the Eurozone accepted euros, they weren’t just thinking of paying their taxes.”

Nobody said there was. And nobody in MMT says that.

Please don’t confuse necessary and sufficient.

Taxes are the starter motor for the acceptance of a particular token. Then you get a cascade effect over the area where that state has enforcing power.

The weaker the state, the less the token is used.

“People in the UK accept English because nearly everybody else in the UK accepts it too. In Ireland, on the other hand, the Irish language is languishing despite its official status because most inhabitants of Ireland speak English.”

And yet Southern Ireland uses the Euro, and prior to that the Punt, and Northern Ireland the Pound, with an abrupt changeover at the border. The difference being which tax authority they are beholden to and which token those tax authorities accept.

“Alan: You are not dealing with my main argument. ”

James, your main argument is based on using a currency that doesn’t satisfy the four basic characteristics of money:

1) durability,

2) divisibility,

3) transportability, and

4) noncounterfeitability

Until you can fix that up your argument is being built on very shaky foundations.

Dear Neil

We may be inching toward an agreement. I still maintain that people can develop a currency or currencies without the state because of the many advantages that a monetized economy has over a barter economy. In a monetized economy, the state may then start taxing in the main currency and eventually become a monetary monopolist. To use another analogy, it wasn’t the Revolutionary government that brought weights and measures to France, but it was that government which standardized them through the metric system and made the metric system obligatory. Spelling is another example of private initiative preceding official standardization. It was only in the 19th century that European governments (except the British) introduced an official spelling. However, they could do so relatively easily because there were already various spellings in existence which resembled each other.

Spelling illustrates both the power of the state and the power of spontaneous consensus. In Turkey, the government decided to replace the Arabic alphabet by the Latin one after WWI, and people accepted it, which demonstrates the power of the state. The reason why it went relatively smoothly is probably that most Turks at the time were illiterate and many of those who could write were already acquainted with the Latin alphabet. In English-speaking countries, the government does not impose an official spelling but everybody slavishly follows the monstrously inconsistent conventional spelling, a clear illustration of the coercive power of consensus.

Cheers. James

Mises Regression Theorem – that’s basically what James is selling. Whereby money is defined as the most tradeable commodity.

Nothing you post James is in any way original.

We can continue the discussion when you explain why Irish isn’t the main language in Ireland, but the Euro is the main currency, and the Punt before it.

You are not bridging away from that one.

Neil:

Why did the Irish government after independence succeed in replacing the pound by the punt but not in replacing English by Irish? Obvious answer: because changing one’s currency is much easier than changing one’s language. A currency can be changed in a very short time, but changing the language of a people usually takes many generations. The English rulers of Ireland didn’t displace Irish by English in a few years. Before the Potato Famine, there was still an Irish-speaking majority in Ireland. The Famine accelerated the decline of Irish because a disproportionate number of Irish-speakers perished or emigrated.

Going from pound to punt or from punt to euro is like going from miles to kms, as Canada did in the seventies. After metrication, Canadians had to remember that 1 mile = 1.6 km, and 1 km = 0.625 mile. Similarly, after the punt became the currency of Ireland, the Irish had to remember that 1 pound = x punt, and 1 punt = 1/x pound. That’s a bit easier, isn’t it, than to learn the Irish language as an adult.

Alan:

I didn’t claim to be original and I don’t believe that the money which we use today is a commodity. However, it is plausible that money started as a commodity, but once a commodity is monetized, it will be demanded mainly as a medium of exchange. To the Incas, gold was still a commodity with great ornamental value. To their Spanish conquerors, gold was mainly a medium of exchange, which they craved so that they could buy all kinds of goods and services with it.

Best wishes. James

“Obvious answer: because changing one’s currency is much easier than changing one’s language.”

But you clearly believe it isn’t – because as you state the government cannot impose a currency and people will only use it if they trust it, and then start taxing in something they use.

So why do they believe the government fiat. Why did the Euro come in, and why did the Punt come in in a very small country that largely uses English and was trading quite happily in Sterling – particularly with the level of exports out of Ireland. Similarly the UK continues to use Sterling even though the majority of its export trade is with Europe and it is part of the European Union – even when the tax authorities offer a foreign exchange service that will take Euros and swap them for Sterling to settle the tax debts.

And the reason is straightforward – because the deemed token is the currency to pay taxes, which then makes it easier to use that than the trading alternative which then causes a cascade effect over the sovereign area.

There is an abrupt change in currency at the Irish border, and the best explanation of that is that the sovereign power changes at that point – and with it who you pay your taxes to and in which currency.

The best explanation is the taxation/sovereign power explanation – since that shows how you can start up a circulation by fiat whether people trust it or not. Particularly as you can demonstrate it yourself if you have kids – using the business card routine.

It explains the extent of currency areas: why some currency areas are smaller than the country and why some (largely the US) are bigger. It explains why it is easy to switch currencies, and it shows why currencies collapse.

I have yet to see a better theory that fits the reality of the situation, and your attempts at an alternative narrative are confused and fragmented at best. The explanation just doesn’t stack up.

Dear Neil

As I said, Canada introduced the metric system in the seventies. All distances are now given in kms, all gasoline is sold in liters, stores charge per kilos. Interestingly, supermarkets will indicate the price of bulk goods per pounds and then charge you per kilos. They may post that cherries cost 4 per pound and then charge you 8.8 per kilo. However, there is one area where metrication failed completely, and that is people’s weight and height. The vast majority of non-immigrant Canadians still give their height in feet and inches and their weight in pounds. Why the difference? Answer: because for those measurements there are no business intermediaries. People buy their gasoline from an oil company and their groceries from a supermarket, but not their height or weight. Metrication involved mainly coercion on businesses, not on private individuals.

Similarly, people do most of their transactions through banks. Changing a currency involves mainly coercion on banks, which are quasi-government institutions anyway. If all transactions were in cash between individuals, then it would be much harder to change the currency, at least if people are using a foreign currency, as was the case in Ireland before the punt.

You said that there is an abrupt change in currency when you go from Ulster to Ireland. Well, there is also an abrupt change in distances when you go from the US to Canada. On the American side, everything is indicated in miles, on the Canadian side in kms. If there were no water between Britain and France, then there would also be an abrupt change in traffic rules when you go from France to Britain. Instead of driving on the right, you now have to drive on the left. In many areas, governments have a strong capacity to impose uniformity, and currency is one of them. My contention is that a government would still have the capacity to impose its own monetary uniformity in the are under its control even if people didn’t have to pay taxes. What is sufficient is that the government is the monopoly issuer of the currency and has power over the banks.

Regards. James

“As I said, Canada introduced the metric system in the seventies.”

They also introduced dual language on everything, yet few speak French. What the temperature of the pools is discussed in depends upon the age of those in the conversation.

Banks offer accounts in all sorts of currencies. I can open a Euro account tomorrow at pretty much any bank that has a reserve account at the Bank of England. I can get mortgages in Euros, and I could even invoice and get paid in Euros if wanted.

Canadians can run dual US dollar accounts – particularly the snow bird generation.

So your explanation doesn’t stack up as sufficient to ensure a circulation. The one thing that forces the circulation of a particular currency is the ability to impose a unilateral debt that can only be settled in that currency. That, ultimately, forces people under those obligations to obtain the currency from the issuer in return for real goods and services supplied to the issuer. Which is how government can reliably provision real goods and services for its own purposes.

And that’s the ultimate point. Government can always provision itself with its paper, and therefore can always get the resources to make things happen.

Neil:

Suppose that the currency of Ruritania is the ruri and that everybody in Ruritania expects the government to fall soon and that the next regime will declare all ruris to be worthless and to introduce a new currency. Why would any seller then accept payment for his goods or services in ruris? Sure, people still owe their taxes in ruris, but since they won’t be able to obtain ruris, they can’t pay taxes either. The government can print ruris, but government employees may prefer to quit rather than to accept payment in ruris. If nobody has any confidence in a currency anymore, then even the obligation to pay taxes in that currency cannot insure that it will be accepted as payment. What ultimately gives a currency value is confidence. That’s why people all over the world accept US dollars. They trust the greenback.

Cheers. James

“f nobody has any confidence in a currency anymore, then even the obligation to pay taxes in that currency cannot insure that it will be accepted as payment.”

You don’t do a very good rendition of there’s a hole in my bucket.

The government has to have the power to enforce taxes – by force if necessary – and it has to supply the currency for goods/services to settle the taxes if there is insufficient in circulation. Bearing in mind that saving is essentially voluntary taxation.

If you are saying that the government has no power to enforce taxes, then yes the currency will fail. If you are saying there is no currency in circulation and the government is refusing to supply any then yes the currency will fail.

All of this is in the description of the *sufficient* conditions for the circulation to function.

Boxing yourself into a corner with a ridiculous self-contradictory example, that pays no attention whatsoever to documented human behaviour is no argument.

Supply the currency to whom and how?

If nobody has any confidence in a currency anymore, then even the obligation to pay taxes in that currency cannot insure that it will be accepted as payment. What ultimately gives a currency value is confidence. That’s why people all over the world accept US dollars. They trust the greenback.

Yes, confidence is necessary. Confidence that the government can enforce tax obligations, confidence that the penalties are undesirable. These confidences are incorporated in the concept of tax-driven money – which analyzes things more deeply than superficial attribution to “confidence”. (Thinking of things creditarily is yet deeper, more trivial and more general – but I don’t think that is what you mean.)

But where does the confidence come from?

The government can print ruris, but government employees may prefer to quit rather than to accept payment in ruris. They will not accept the ruris only if they expect them to be worthless. If they actually do become worthless, then this does not contradict standard MMT, which is meant to apply (at least facilely) to working governments, not regime changes.

If they don’t become worthless – and the citizens of Ruritania constantly, irrationally refuse to accept ruris, even though experience has shown that they need them to not be imprisoned, then them guys are just plain nuts. But this doesn’t apply to any society ever. MMT is meant to apply to societies of ordinary human beings, not characters in modern pseudophilosophical word games.

Citizens of real human societies have the rational confidence – the rational expectation 🙂 that they will need to perform, satisfy social obligations, like paying taxes or suffer the consequences. A working tax system certainly is quite sufficient for acceptance of a currency. I agree with Alan, this is circling around Mises Regression “Theorem”. The problem is thinking of money as a mere, bare commodity, a thing – which it never was or could be.

Dear Some Guy

Suppose that we have a government that can finance itself entirely through the profits from the oil fields which it owns, so that it never collects any taxes. Could such a government still create and run a fiat currency.? I would say that it can, but MMT’ers have to argue that it can’t.

A monetized economy has such an advantage over a barter that it will come into being spontaneously, just as writing can come about without a government. Once money exists and people are used to getting paid in money instead of in kind, the government can then take control of it, just as a government can try to regulate writing once writing exists.

Bulgaria is now a member of the EU and, as far as I know, the only EU member which uses the Cyrillic alphabet. Suppose that the Bulgarian government wants to introduce the Latin alphabet because it wants to have the same alphabet as the other 27 EU members. Instead of making Latin mandatory, the Bulgarian government only stipulates that the Latin alphabet will be used by the government in its correspondence with the citizens. For all other purposes, people are free to use Cyrillic. Is the Latin immediately going to drive out Cyrillic? I doubt it. Similarly, if a currency is mandatory only for the payment of taxes, then it may well remain marginal. It will not remain marginal if people also have other reasons to accept the currency in which they are obligated to pay taxes.

Regards. James

Suppose that we have a government that can finance itself entirely through the profits from the oil fields which it owns, so that it never collects any taxes. Could such a government still create and run a fiat currency.? I would say that it can, but MMT’ers have to argue that it can’t.

It isn’t clear what you mean by a government financing itself through profits from oil fields. If you mean that it sells oil to the nongovernment in return for the “fiat” (as if there were any other kind!) currency it had issued, then this is precisely what MMT describes. Far from “MMT’ers have to argue that it can’t” – MMTers can and do so argue. Taxes can cover fees and fines paid to the government, which were historically more important.

Paying a tax to the government is buying something from the government, the private sector getting a “real” benefit in return, while being paid by the government is selling something to the government – the government getting a real benefit in return for credit. As Mitchell-Innes describes, the usual way of thinking gets it backwards. As in your pig example above, I think. Government spending is the real taxation – ancient taxation-in-kind – like “paying taxes with a pig” – was what we now call government spending (the village got credit in the Pharaoh’s treasury for having paid its pig-tax), not modern financial taxation (which happened when the villages’ treasury credit expired).

“If inflation is caused by the monetary policy of the government, then it is not unreasonable to demand that people who have savings with the government be compensated for that.”

That is a partisan political position. An alternative political position holds that the government has a superior obligation to the national interest, and if the citizens find the demands of the national interest upon their fiat currency savings to be onerous, then they are perfectly free to place their savings elsewhere.

“If there is deflation due to a supply shock, then indexing will reduce the redemption value of the bonds.”

But if there is negative real growth and positive inflation due to a supply shock, then the inflation indexing becomes itself inflationary. (And positive inflation with negative real growth are the “stylized facts” of supply shocks – deflation is usually associated with demand deficiency.)

“A negative rate of inflation should mean a decrease in the redemption value of bonds.”

But this is only non-inflationary if you strip out the part of inflation which is due to changes in the terms of trade with the rest of the world. You can easily have consumer price inflation in the headline rate and producer price deflation in the inflation rate stripped of changes to the terms of trade.

Unfortunately, quantifying this effect turns out to be a non-trivial exercise – particularly in real time.

“It is true that a modern fiat currency is a government creation, but people accept it because it has many advantages, not just because they are coerced into paying taxes. Suppose that the government of Ruritania owned so much oil that oil profits were sufficient to finance all government activities. Then there would be no taxes at all, but the Ruritanian government could still be the sole issuer and manager of ruris, and Ruritanians would still accept the ruri for their transactions.”

I can’t off the top of my head think of any real-world example of such a country that hasn’t dollarized.

“I still maintain that people can develop a currency or currencies without the state”

That has never been in dispute. Any person or entity that wields *power* over people can issue tokens of that power, and have them function as a private currency within its sphere of power. The state is just one of many powerful institutions and individuals, and not in every relationship the most powerful.

“However, it is plausible that money started as a commodity”

You may find it plausible. I don’t, because I understand that money is a token of a power relationship. But either way, according to available evidence it is counterfactual.

“Suppose that the currency of Ruritania is the ruri and that everybody in Ruritania expects the government to fall soon and that the next regime will declare all ruris to be worthless and to introduce a new currency. Why would any seller then accept payment for his goods or services in ruris?”

You are giving far too much weight to expectations, and far too little to everyday necessity. People kept transacting commerce in Reichsmark and Confed greenbacks right up until they were officially annulled, even though anybody who had eyes to see with could tell that they would soon be worthless months before the official announcement.

Expectations are all well and fine for the leisure class playing on the stock exchange. But the great masses of common people have to buy real food in real time using the coin of the realm.

– Jake

Jake and Some Guy:

Thanks for your replies. I won’t respond because I have a bad cold, which saps me of energy (Canadian winters). James