The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The confidence tricksters in the economics profession

There was an extraordinary report in the Wall Street Journal last week (September 19, 2013) – Austerity Seen Easing With Change to EU Budget Policy – which considered the political machinations in Europe that may lead to the EU relaxing some of the harsh austerity measures that have deliberately pushed millions of Europeans onto the jobless queues. I say extraordinary because it shows how flaky the mainstream of my profession is and how they seem to think everyone else is stupid and as long as they dress up their so-called “analysis” in the opaque language of the cogniscenti, the general public will believe anything. This includes the proposition that underpins the on-going and harsh austerity programs in Europe that a reasonable definition of full employment in Spain, for example, is consistent with an unemployment rate of 23 per cent (and near to 60 per cent youth unemployment). They are trying to keep a straight face when they report that their estimates of full employment have moved from around 8 per cent unemployment to 23 per cent unemployment in a few years. It beggars belief and these confidence tricksters should be called to account.

The following blogs are background to today’s blog:

- The dreaded NAIRU is still about!

- NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy

- Structural deficits – the great con job!

- Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers

A summary of the main points will help:

The federal budget balance is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa.

The budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government. So if the budget is in surplus we conclude that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

However, the complication is that we cannot then conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty is that there are automatic stabilisers operating.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending.

Budget Balance = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the Budget Balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the Budget Balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the Budget Balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the Budget Balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into or is in deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

To overcome this uncertainty, economists devised what used to be called the Full Employment or High Employment Budget. In more recent times, this concept is now called the Structural Balance. The change in nomenclature is very telling because it occurred over the period that neo-liberal governments began to abandon their commitments to maintaining full employment and instead decided to use unemployment as a policy tool to discipline inflation. I will come back to this later.

The Full Employment Budget Balance was a hypothetical construct of the budget balance that would be realised if the economy was operating at potential or full employment. In other words, calibrating the budget position (and the underlying budget parameters) against some fixed point (full capacity) eliminated the cyclical component – the swings in activity around full employment.

So a full employment budget would be balanced if total outlays and total revenue were equal when the economy was operating at total capacity. If the budget was in surplus at full capacity, then we would conclude that the discretionary structure of the budget was contractionary and vice versa if the budget was in deficit at full capacity.

The calculation of the structural deficit spawned a bit of an industry in the past with lots of complex issues relating to adjustments for inflation, terms of trade effects, changes in interest rates and more.

Much of the debate centred on how to compute the unobserved full employment point in the economy. There were a plethora of methods used in the period of true full employment in the 1960s. All of them had issues but like all empirical work – it was a dirty science – relying on assumptions and simplifications. But that is the nature of the applied economist’s life

Things changed in the 1970s and beyond. At the time that governments abandoned their commitment to full employment (as unemployment rise), the concept of the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (the NAIRU) entered the debate – see my blogs – The dreaded NAIRU is still about and Redefing full employment … again!.

The NAIRU became a central plank in the front-line attack on the use of discretionary fiscal policy by governments. It was argued, erroneously, that full employment did not mean the state where there were enough jobs to satisfy the preferences of the available workforce. Instead full employment occurred when the unemployment rate was at the level where inflation was stable.

NAIRU theorists then invented a number of spurious reasons (all empirically unsound) to justify steadily ratcheting the estimate of this (unobservable) inflation-stable unemployment rate upwards.

The NAIRU has been severely discredited as an operational concept but it still exerts a very powerful influence on the policy debate.

Further, governments have become captive to the idea that if they try to get the unemployment rate below the “estimated” NAIRU using expansionary policy then they would just cause inflation. I won’t go into all the errors that occurred in this reasoning. Our 2008 book – Full Employment Abandoned with Joan Muysken is all about this period.

Now I mentioned the NAIRU because it has been widely used to define full capacity utilisation. If the economy is running an unemployment equal to the estimated NAIRU then the mainstream concluded that the economy is at full capacity.

Of-course, they kept changing their estimates of the NAIRU which were in turn accompanied by huge standard errors. These error bands in the estimates meant their calculated NAIRUs might vary between 3 and 13 per cent in some studies which made the concept useless for policy purposes.

But they still persist in using it because it carries the ideological weight – the neo-liberal attack on government intervention.

So they changed the name from Full Employment Budget Balance to Structural Balance to avoid the connotations of the past that full capacity arose when there were enough jobs for all those who wanted to work at the current wage levels. Now you will only read about structural balances.

And to make matters worse, they now estimate the structural balance by basing it on the NAIRU or some derivation of it – which is, in turn, estimated using very spurious models. This allows them to compute the tax and spending that would occur at this so-called full employment point. But it severely underestimates the tax revenue and overestimates the spending and thus concludes the structural balance is more in deficit (less in surplus) than it actually is.

They thus systematically understate the degree of discretionary contraction coming from fiscal policy.

So they are trying to tell us that the business cycle moves around a fixed point – currently around 5 per cent unemployment – and above that the economy is operating with spare capacity and below it the economy is operating over full capacity.

The NAIRU is tied in with estimates of the Output Gap.

As I note in this blog – Structural deficits and automatic stabilisers – the problem is that the estimates of output gaps are extremely sensitive to the methodology employed.

They rely on an estimate of potential GDP, which is non-observable. It is clear that the typical methods used to estimate potential GDP reflect ideological conceptions of the macroeconomy, which are problematic when confronted with the empirical reality.

For example, on Page 3 of the CBO document – Measuring the Effects of the Business Cycle on the Federal Budget – we read:

… different estimates of potential GDP will produce different estimates of the size of the cyclically adjusted deficit or surplus …

CBO define Potential GDP as “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use.

So how do they estimate potential GDP? They explain their methodology in this document.

CBO say that they:

They start with “a Solow growth model, with a neoclassical production function at its core, and estimates trends in the components of GDP using a variant of a tried-and-tested relationship known as Okun’s law. According to that relationship, actual output exceeds its potential level when the rate of unemployment is below the “natural” rate of unemployment) Conversely, when the unemployment rate exceeds its natural rate, output falls short of potential. In models based on Okun’s law, the difference between the natural and actual rates of unemployment is the pivotal indicator of what phase of a business cycle the economy is in.

The resulting estimate of Potential GDP is “an estimate of the level of GDP attainable when the economy is operating at a high rate of resource use” and that if “actual output rises above its potential level, then constraints on capacity begin to bind and inflationary pressures build” (and vice versa).

So despite saying that their estimate of Potential GDP is “the level of output that corresponds to a high level of resource … labor and capital … use” what you really need to understand is that it is the level of GDP where the unemployment rate equals some estimated NAIRU.

Intrinsic to the computation is an estimate of the so-called “natural rate of unemployment” or the Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment.

Given the history of estimates of the NAIRU, the “steady-state” unemployment across different nations has varied dramatically from time to time – with sudden rises projected for no apparent reason other than the actual unemployment has just risen. These estimates would hardly be considered “”high rate of resource use”. Similarly, underemployment is not factored into these estimates

The concept of a potential GDP in the CBO parlance is thus not to be taken as a fully employed economy. Rather they use the standard dodge employed by mainstream economists where the the concept of full employment is not constructed as the number of jobs (and working hours) which satisfy the preferences of the available labour force but rather in terms of the unobservable NAIRU.

The problem is that policy makers then constrain their economies to achieve this (assumed) cyclically invariant benchmark. Yet, despite its centrality to policy, the NAIRU evades accurate estimation and the case for its uniqueness and cyclical invariance is weak. Given these vagaries, its use as a policy tool is highly contentious.

The OECD’s method is outlined in – Long-term growth scenarios – which is Working Paper No. 1000 by Johansson et. al. (2013) published by the OECD Economics Department Working Papers series.

The IMF follow a similar method although the way they project the estimates can vary.

There is a Working Group within the European Commission’s Economic Policy Committee (EPC) called the – Output Gaps Working Group.

It say that the:

The Group is mandated to ensure technically robust and transparent potential output and output gap indicators and cyclically adjusted budget balances in the context of the Stability and Growth Pact. The group should as appropriate develop progressively the commonly agreed method for calculating output gaps. This is particularly important in view of the 2005 agreements on the Stability and Growth Pact.

I was amused at the “transparent” bit – which in any reasonable language tells us that there should be a raft of published material including time series data, technical manuals etc – to let us all know about the work of this important group.

I have sought such information with no success.

The Publication Page for the EPC lists its “10 latest publications” – the last being a 2011 Report on Aeging. The other reports go back to 2008 and are dominated by ageing and pension analysis. Standard scaremongering.

The latest report on estimating potential output and output gaps is 2004. Very transparent!

The problem is that this Group seems to be at the centre of why millions of Spaniards have been deliberately pushed out of work by the Troika (IMF, ECB and EC) in tandem with an obsequiously compliant Spanish polity.

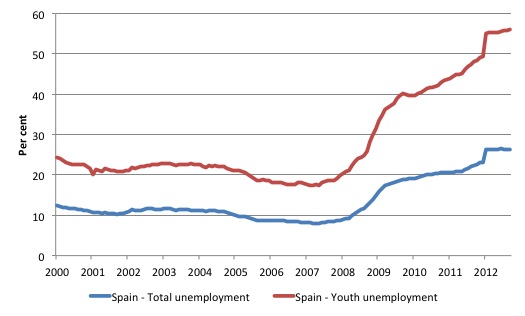

Consider the following graph which shows the total and youth (15-24) unemployment rate in Spain from 2000 to 2013 (September). The data is from Eurostat.

Any reasonable interpretation of this graph and a knowledge that as the unemployment rates spiralled, real output growth collapsed, would lead to the conclusion that the post-2007 period is a cyclical event.

Structural events are typically slow moving. A nation doesn’t suddenly lose its productive capacity (unless there is an extraordinary event like a tsunami or earthquake or war). Labour forces do not suddenly alter their preferences between their desire to work and their desire to retire early, or work less, or “enjoy leisure”.

Labour forces do not suddenly become indolent. Inasmuch as these attitudinal changes ever occur, they occur over time and are not discernable on a month to month basis.

So it would be hard to consider the rise in unemployment in Spain from its average between 2000 and 2007 of around 10 per cent or 8.7 per cent between 2005 and 2007, to 16 per cent in early 2009 and 26 per cent or so in early 2012 could be explained in structural terms.

In other words, it would be extraordinary to assert that the NAIRU had risen in 3 short years from 8 per cent to 26 per cent. It might be that productive capacity has been wiped out and the inflation barrier is now hit at a real GDP level some 20 or more percent below the level of early 2008, but that doesn’t square with the real output gap estimates of the OECD or even the IMF.

Why does this all matter?

Let’s return to that Wall Street Journal article (September 19, 2013) – Austerity Seen Easing With Change to EU Budget Policy.

In that article by journalist Matthew Dalton we read that:

European finance officials tentatively approved a change to the region’s budget policies that is likely to lighten the austerity required of Spain and other countries hardest hit by the sovereign-debt crisis.

A reasonable person would consider that a policy change – a relaxation of austerity, which has crippled the Spanish economy and caused the unemployment crisis that is depicted in the graph above.

But that is not the way the European Commission officials are presenting it.

These zealots are trying to convince us that their policy structures are completely consistent and all that might have changed is that their estimates of the “structural deficit” could be revised.

The Stability and Growth Pact appended with the so-called Fiscal Compact in Europe now requires that EU governments maintain structural deficits “under 0.5% of a country’s gross domestic product” (more or less).

The actual deficit can be at 2 per cent (as in the SGP) but the structural component should be under 0.5 per cent.

Cue – the Output Gaps Working Group introduced above.

They have informed officials that deficits in the Eurozone are mostly structural in nature rather than cyclical, which defies other official data (say from the OECD and the IMF) and basic common understanding that it is the other way around.

The WSJ article says:

In a weak economy, with mass unemployment and many factories running at only a fraction of full capacity, government revenue is depressed and social spending is elevated.

The structural deficit in these circumstances will be lower than the actual deficit, representing the assumption that once the economy strengthens, the real deficit will naturally narrow, without cuts to government spending or tax increases that have proved politically toxic.

But Europe’s current method for calculating the structural deficit has determined that much of the budget deficits seen in the bloc’s weakest economies are structural, or built-in, not cyclical. That means they will persist even after the economy has returned to full strength. So austerity measures-spending cuts or higher taxes-are required.

So the first two paragraphs of the quote would be the reasonable interpretation of the European situation at present. But the ideologues of the EU defy that logic.

How can they do that?

Simple, they have determined that:

… some of the bloc’s weakest economies are operating relatively close to full capacity … For example, the latest commission estimate is that the Spanish gap is just 4.6% of gross domestic product, despite nearly 27% of Spain’s labor force being officially unemployed … The commission believes that the “natural” rate of unemployment – if the Spanish economy were operating at full potential – is 23%.

That is the NAIRU has spiralled and full employment for Spain is consistent with an unemployment rate of 23 per cent.

If you believe that then please E-mail me and I will arrange transfer of ownership to you of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, with the Sydney Opera House thrown in for good measure, all for the small fee of $A1000. What a deal! Get in fast!

The EC is now considering the veracity of their estimates and Spain is leading a group of nations to force a change in the estimates of the output gap and a reduction in the estimated NAIRU.

The WSJ say:

The new methodology proposed by Spain could halve its estimated structural deficit this year and cut it by two-thirds next year, according to the Spanish finance ministry. That could mean a significant reduction in the amount of austerity that the beleaguered Spanish public would have to endure.

The witchdoctors and shamans are alive in Brussels and we will follow this story.

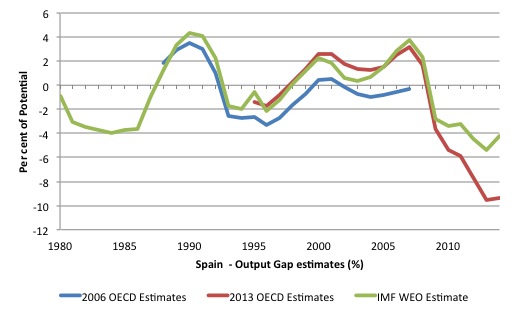

To demonstrate that point, the following graph compares the OECD output gap estimates for Spain published in their 2006 Economic Outlook to the most recent OECD estimates available (from HERE and the IMF World Economic Outlook estimates (as at April 2013).

The estimates for 2006 AND 2007 in blue are projections (data was published in 2006) while the 2013 and 2014 estinates in green and red are projections.

You can see that while the IMF and more recent OECD estimates coincide up to the crisis, they deviate quite sharply after 2009, reflecting the IMFs determination to under-estimate the extent of the crisis (as a means of selling its austerity policy line).

Comparing the two OECD series is interesting. The most recent estimates suggest that between 1998 and 2008 the OECD estimated that Spain was operating above is potential capacity whereas the earlier estimates suggested this occurred in only two of the years (2000 and 2001).

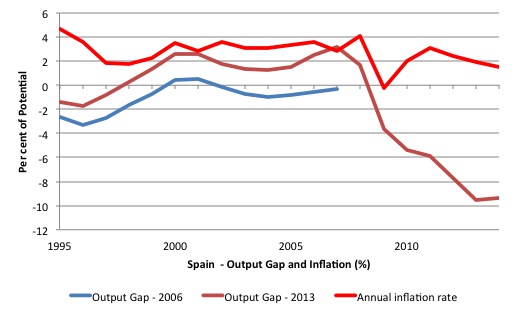

If the Spanish economy was really operating at such high-pressure we would expect an acceleration in the inflation rate. The next graph adds the annual inflation rate for Spain to the output gap series from 1995 and you can see that the inflation was low and stable throughout this supposed period of overheating.

That should provide a cautionary note when one is assessing the veracity of these output gap estimates.

But further, and relevant to the topic of today’s blog, note that, for example, in 2007, just before the crisis began the OECD was estimating that the output gap was 3.5 percent (which means actual output was estimated to be about the potential capacity of the economy), an assessment that the IMF supported.

If we match that to our understanding of the decomposition of the budget balance into cyclical and structural components then this implies that between those years 1998 and 2008, there was a negative cyclical component, given that the cyclical component measures the portion of the budget outcome that is the result of the economy being above or below full employment (that is, in conceptual terms, an output gap = zero).

Examining the OECD’s own estimates of the structural decomposition of the Spanish budget balance shows that Spain ran small deficits (as a % of GDP) from 1998 to 2004 and then small surpluses between 2005 and 2007, before the sudden and significant shift into deficit as the crisis unfolded.

But even in 2008, as the budget balance went from a 1.9 per cent surplus (2007) to a 4.5 per cent deficit (as a % of GDP), the OECD was still claiming the economy was operating above full capacity, given its estimate of the structural deficit was 5.7 per cent (that is, the cyclical component of the -4.5 per cent budget outcome was a positive 1.2 per cent.

Between the end of 2007 and the end of 2008, the Spanish national unemployment rate moved from 8.8 per cent to 14.9 per cent. What possible explanation could emerge to suggest that the economy was still producing above its potential.

The lack of internal consistency with all these estimates beggars belief.

But the problem really isn’t just that different methodologies or changes to samples or whatever else is involved produce different estimates. The problem isn’t just that the actual movements in unemployment and inflation bear no relation with the movememnt in estimated output gaps and that these estimates don’t align with the decompositions of the budget balances into cyclical and structural components.

The problem is that these estimates are used to guide and justify policy positions and when errors are made millions can lose their jobs – and it is never the economists who produce the error-prone estimates that join the jobless queues.

For example, in 2008, the policy implication of the OECD (and IMF) output gap measures was that the Spanish economy was overheating. The OECD’s budget decomposition data suggests that the sharp rise in the deficit in 2008 was all due to discretionary changes in Spanish government fiscal policy – which leads to accusations of laxity and profligacy.

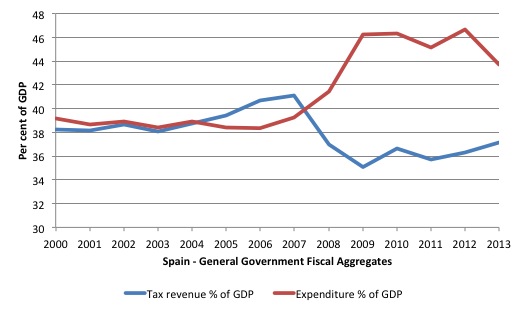

The next graph shows total general government revenue and expenditure for Spain between 2000 and 2012 (from IMF WEO, April 2013) as a per cent of GDP.

It depicts the classic fall into deep recession. Revenue plummets as economic activity declines sharply and income falls and government spending rises as the call on the welfare budget (at existing rates and programs) rises. Some of the increase in spending in the early days of the crisis was related to discretionary stimulus measures but a significant portion was related to the slump in real GDP growth.

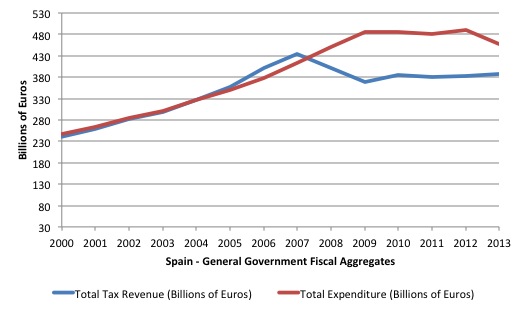

The following graph shows the same data in billions of Euro rather than expressing it as a share of GDP. The austerity set in in 2009 and beyond.

But the point is that if the economy was really operating above full capacity in 2008, then tax revenue would not have collapsed in the way it did.

It is obvious from any reasonable standpoint that the Spanish budget balance had a large cyclical component in 2008 despite the OECD (and IMF) estimates to the contrary.

Conclusion

My profession shines brightly in these sorts of situations – not!

The future generations will not look back on us very kindly. They will categorise my profession as confidence tricksters or worse. I wish I had taken up archeology or anthropology!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I for one am thankful, that you Bill Mitchell, did choose economics as your profession! Your blog has been a real eye opener, showing us a reality one would never have believed possible. A complex society only functions when we all feel we can trust in others operating with honesty, integrity, and generally working toward the common good.

Professor Mitchell

I have a real feeling of despair and complete inadequacy to make a difference and blogs like yours and those of a few other enlightened individuals have and still do continue to offer me hope for this debacle to be sorted out.

Please keep up the great work.

Your voice is being heard albeit by a minority, but it is growing.

Brian

I’m curious as to how the methodology can be changed… From what I’m learning, there are trusted economic bodies that rely on flawed methodology, ratings agencies that apply their ratings based on flawed methodology, and policy makers relying on this methodology, commentators who perform analysis and predictions based on this methodology, and ultimately a public that understands analogies and principles that underpin this methodology.

From a scientific perspective, it wouldn’t be enough to simply create a new model that explains past events, but must predict with greater accuracy the future events. Applied economics appears to be rife with uncertainty about the future irrespective of the methodology used, and those who rise to the top tend to make the big predictions and be right.

I haven’t done enough of a deep analysis of your blog to say whether you’ve been making distinct predictions in past entries that can be shown to have come true, but isn’t that a solid step towards dismantling the erroneous logic that seems to be so pervasive? What more can be done?

Well I can think of one more thing that can be done, should be done, and (if you’re ever going to be taken seriously by the mainstream) must be done: stop advocating a return to the days of continuous deficits!

One thing I quickly learned from this blog is that MMT tells us that it’s the combination of public and private spending that determines economic activity, hence it is the combination of fiscal and monetary policy that’s important. Yet you’re obsessed with the first and dismissive of the second. I don’t dispute there are situations where only fiscal policy is effective, but that doesn’t mean it should be the tool of choice in other situations. And given the choice between continuous deficits with high interest rates or structural surpluses, cyclical deficits and low interest rates, I’d much rather have the latter.

Aidan

i’m curious. You appear to understand MMT principles but instead of choosing to express outrage at what is going on or suggest possible paths for the future you choose instead to have a go at Professor Mitchell for not making himself sufficiently understood to morons.

Why is that ?

Andy –

Bill’s expressed so much outrage at what is going on that any more would be redundant.

I’m guessing by morons you mean mainstream economists. Bill already knows the value of making himself sufficiently understood by them; he’s told us it was part of his reason for studying econometrics.

But not all non MMT economists are morons, and even if they were, explaining things to the general public is also important. And people, particularly outside their main field of interest, tend to dismiss everything if they find even one logical flaw (which is one reason why the work of Marx is so often ignored nowadays).

Bill has a lot more in common with mainstream economists than he likes to think, and unfortunately in this instance that includes clinging to a belief in the absence of any supporting evidence.

I’m not sure what you mean wbout suggesting a way forward. What I’d really like to see is an MMT compliant method of cost benefit analysis, but I’m not holding my breath! I’ve previously suggested in the comments that he write about the relative effects of changing taxation and government spending rates v interest rates. But instead he prefers to express his predictable outrage at decisions and claims that are outrageous but predictable.

Bill, if you’re ever ready to go forward, I’ve no shortage of suggestions.

Aidan

Why are those the only options? The choices that countries actually face are both wider – in general – and more restricted – in the case of any particular country. Continuous deficits are unavoidable unless the nation in question exhibits negative net private sector saving and/or trade surpluses. The first becomes damaging and the second is clearly not possible for all nations. So why your hostility to deficits?

The more Aidan writes, the more people will be convinced that MMT is the best solution.

Well done Aidan. Keep up the good work.

Dear Aidan (at 2013/09/26 at 19:12)

I have actually dealt with this issue often. For example, https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=6796

I also remind you of Treasury modelling in late 2009 presented here – http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1686/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=Australian_Business_Economists_Annual_Forecasting_Conf_2009.htm

They estimated the impact of the rapid reduction in interest rates in 2009 by the Reserve Bank on GDP growth rates and concluded that:

So the discretionary fiscal policy changes were estimated to be around 2.4 times more effective than monetary policy changes (which were of record proportions). That is a common result in the empirical literature across a number of nations.

You might like to alter your straw person!

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill

I am an engineer who has studied enough economics to follow your analysis with great interest, it is only a glimmer but you give me some hope. I know that as an economist you cannot address social consequences though of course you refer to the catastrophic affect on ordinary people which are the result of these policies.

I have traveled internationally and worked with transnational corporations and governments both domestic and foreign.

Frankly the social effects of these levels of unemployment terrify me. The consequences will without doubt lead to be massive growth of organized crime, terrorism and political violence. It is incredible that Europeans, of all people, are ignoring recent history which is almost within our own life time.

Even if your analysis is wrong and we get a certain level of inflation it would be a bagatelle compared to what will eventuate as a result of these in human policies.

Mexico is a terrible example of our destination.

I recently watched the performance of an ex- colleague of yours making his bid for a place in the spot light on the subject of global warming and to advance his academic career. Obviously economists are not the only profession which has problems

Regards

Daforad

FlimFlamMan –

Unless we want higher inflation (which I don’t see as desirable) then when the economy’s at capacity there’s always a tradeoff between fiscal policy and interest rates. There may be times when trade surpluses skew the balance, but as you say, that’s clearly not possible for all nations.

You’re far too quick to dismiss negative net private sector saving as damaging. I think the private sector (as well as the public sector) should invest more in increasing productivity, and that investment should not depend too much on what it already owns. The lower the interest rate, the more businesses can afford to invest and the lower the cost of servicing the same amount of debt will be.

I think we should aim for permanently low interest rates. A broad based land value tax would be required to prevent this from resulting in a housing bubble.

Bill –

You’re the one resorting to strawmen. As I said earlier, I don’t dispute there are situations where only fiscal policy is effective.

But you have been remarkably silent on the comparative effects in situations where the economy is at or near capacity.

“The lower the interest rate, the more businesses can afford to invest and the lower the cost of servicing the same amount of debt will be.”

I thought that this nonsense was all sorted out in 1936? Apparently not.

“But you have been remarkably silent on the comparative effects in situations where the economy is at or near capacity.”

That’s because that is a special case that is rarely, if ever, an issue. Yet economist mostly seem to sit there fretting about that situation as though it is the only one that actually matters. Which is frankly a neurotic situation – given that the majority of the time the problem is a shortage of effective demand and blockages on the supply side often caused by oligopolistic behaviour.

The MMT position, AIUI, is that monetary policy is a blunderbuss, with more blunder than bus and has very little control power that isn’t based upon delusional understanding of the way humans work.

Therefore it is dangerous to play about with, has distributional effects we don’t understand and doesn’t do what people think it does.

So you follow the functional finance approach which is to set monetary policy at the level required to encourage the appropriate level of investment in the economy. And pretty much leave it there. So interest rates at X%, loan to value ratios at Y, capital requirements at Z, etc.

Likely in a lot of countries the base rate should be zero, and the central bank operate on an overdraft basis to provide the regulated banks with whatever liquidity they require. In return the banks sign up for a straitjacket that constrains their lending behaviour tightly. Any reduction in bank lending capacity then gives scope for large tax cuts, or additional government investment spending.

The control of the economy over the business cycle is then done via enhanced automatic stabilisers that add and withdraw from the economy to keep it cycling within an acceptable range. The primary tool being the Job Guarantee.

At least that’s the executive summary I get from MMT.

Aidan:And given the choice between continuous deficits with high interest rates or structural surpluses, cyclical deficits and low interest rates.

But MMT is not for continuous deficits with high interest rates, but for low or zero interest rates, and in particular for stable rates. The deficits are a logical outcome of desirable aims, not a goal in themselves. As Keynes, Lerner, Domar, Harris, Godley, Fullwiler etc understood and showed, Functional Finance is sounder than Sound Finance. So in all likelihood, MMT deficits, while probably continuous, would tend to be small deficits, because they would be good deficits.

I think we should aim for permanently low interest rates. A broad based land value tax would be required to prevent this from resulting in a housing bubble. Again, whether or not this would result in a housing bubble, these are MMT proposals. Your objections are thus very hard to understand, except for the straw man which Bill dissects above.

Unless we want higher inflation (which I don’t see as desirable) then when the economy’s at capacity there’s always a tradeoff between fiscal policy and interest rates. Yes, inflation is bad. But your meaning of an “always” tradeoff is obscure. And if my guess of your meaning is correct – the mainstream one? – quite wrong. It’s always more complicated than the “always” which the mainstream & even some “heterodoxers” thoughtlessly hold as an axiom so fundamental that it is never stated, let alone examined. Frequently the best thing to fight inflation at full capacity would be low rates, not high ones.

Neil Wilson, it’s only because of the GFC that it’s rarely if ever an issue. Australia was running into capacity constraints before that and had resorted to raising interest rates multiplle times to control inflation. And although MMT allows us to run a bit closer to those constraints without hitting them (by varying government spendinng according to region) the fact remains that those constraints are still there.

Anyway, the fact remains that if governments based their decisions on MMT then the economy would always run at or near capacity so it would cease to be a special case.

Yes monetary policy is a blunt tool, but it’s still a very useful tool, and the most effective tool we have to influence private spending. But I would be in favour of regulating the banks more tightly, though not quite as tightly as Bill favours. I’d set high capital requirements below which they would be prohibited from dividend payments or share buybacks.

I don’t think the nominal interest rate should be set as low as zero, but I do consider it an appropriate target for real interest rates.

Some Guy – I agree the fiscal situation should always be the logical outcome of desirable aims rather than the goal itself. But to claim that continuous deficits are the logical outcome of those aims is quite frankly delusional! Government deficits would of course be the immediate outcome at the moment due to the economic cycle, but once the private sector recovers it is likely to run much bigger deficits without high interest rates forcing it to net save, hence the logical outcome would be for the government to run surpluses.

The problem is Bill’s failing to recognise this, and seems to be relying on the unsupported conjecture that the private sector is likely to net seve because it’s normal!

I’ve always regarded interest rates as aninefficient tool to control inflation, as the cost of living pressures they impose on mortgage holders would, on the face of it, logically make them inflationary. Yet there does seem to be a lot of evidence that inflation targetting works, and MMT explains why: all other things being equal, the lower the interest rates are, the more money the private sector adds to the system. Higher interest rates mean less money. And the more money increases compared to productivity, the more inflation we get.

There appears to be some myopia in the choice of indicies for regional health. Nature never allows any individual or group there of to grow for an extended period at a rate that continually doubles the portion of the resources commanded by that sector.

Herman Daley and Albert Bartlett have shown this conundrum in exquisite detail. We have allowed the scientific and financial community to put in place mechanisms that increase both the population and concentration of wealth. These two issues combined with the impossibility of controlling the access to power by “jerks”, a technical term for sociopaths and worse, have put us on a track that will end with natural responses equivalent to your automatic stabilizers. This time the impact will be felt by us all.

To summarize my last comment, we need to enable growth of the young and small entities for appropriate lengths to time and remove, stall, and or replace the old and over large structures from the past. Implicit in this is that it is okay for new entries and old entities to fail and for the replacements to grow for a limited time from the detritus left by their demise. I see no other way to accomplish this than to institute a constrained rate of allowable growth that is applicable to individuals and entities that will include negative rates (ie: a mandated declining growth rate for entities over a certain size or age). One method to accomplish this is a mandated taxation system that redistributes resources to the small from the over large.

The use of GDP growth as a measure of regional success is completely inappropriate.

“Yes, inflation is bad.”

Is it though.

Or is it just accelerating inflation that is bad. In other words a rate of change that changes rapidly.

As far as I can see the only people that lose out with inflation are private money lenders. It helps pretty much everybody else. (And that’s with inflation defined as a general rise in prices – including wages and state pensions).

Inflation, interest rates and lending have become the focus because the private money lenders are in charge.

Perhaps it is time for them to abdicate.

Aidan

When an economy is operating at capacity there is a trade-off, yes, but it is between spending and other spending, competing for whatever real resources are available. Interest rates can influence that spending, but with various costs and income effects the magnitude, and even direction, of that influence is not clear.

My aversion to increasing private sector debt comes from example after example, in numerous nations, of that debt becoming unsustainable after even a modest economic shock. Or no shock at all; the debt level can become its own shock.

Governments can step in at that point with support, and did so, insufficiently, after the GFC. Such action is just covering for past failure though. Failure in the government’s mission to support public purpose, by encouraging warped returns to capital vs labour; by encouraging asset bubbles as a dangerous substitute for decent wages; failure to take action on the outright criminality which surrounds those bubbles, and so on.

I would rather avoid all that in the first place. Given that private sector saving has been, until the last couple of decades or so, the usual state of affairs for many nations, then government deficits will be the natural result where imports are positive. Not the goal, just the non-scary result.

Just to end on a note of agreement; I’m fully in support of this. LVT was one of the first light-bulbs that pinged into life as I tried to understand what happened in 2007/2008 – and starting long before that as it turned out.

FlimFlamMan

As I explained to Some Guy, the direction of the effect of interest rate changes on inflation is quite clear. Their magnitude isn’t, just as the magnitude of the effects of tax rate changes wouldn’t be clear.

How do you think the debt level can become its own shock?

Unless you’re referring to corporate welfare (which I’m opposed to) government action doesn’t cover up past failure, but rather it compensates for its effects. And that’s a good thing, as it means the government can temoorarily increase its spending without having to do anything to discourage private spending.

Higher interest rates give more reward to capital for doing nothing, so if you’re concerned about warped returns then low interest rates are a big part of the solution. But private sector deficits are the natural outcome of that. It’s time to start overcoming your irrational fear of that.

Aidan

For some sets of economic variables and their specific values your ‘more money/less money’ explanation will fit; for others – tilted toward significant debt held by significant numbers of people with a higher propensity to spend than the debtors, for example – it won’t. Or rather, the direction of the ‘more money/less money’ will be subject to reversal[s]. Which is fine provided we know which set of variable values we were operating under.

Given the scale and complexity of national economies, and their interactions globally, combined with the nasty habit variables have of varying, we may not know. Worse still, we may think we know but be mistaken.

AIUI, private sector debt sets up the conditions to become its own shock when, due to its own growth, it can no longer be serviced out of income. The shock itself may be delayed by selling off assets or engaging in fraud, but the first is unavailable at scale – fallacy of composition – and the second is criminal. Bill, Randy Wray, and others cover this extensively, including those outside MMT; Steve keen for example. And of course not forgetting Hyman Minsky.

I didn’t say cover up past failure, I said cover for past failure; not “Oh crap, we screwed up, how can we keep people from finding out?” but “Oh crap, we screwed up, how can we fix the damage?”. As you say, fixing the damage is a good thing, but an even better thing is not causing or allowing it to begin with. Especially when the ‘fix’ is insufficient, as it has been since 2008 in most – all? – countries.

The problem with the current way we create debt to the private banking system and assess value is that debt results in paying multiples of the amount borrowed to some holder of existing value who is not part of the economy where the debt is incurred. Thus each debt becomes a mine where a local value is extracted leaving the area with less than it had before. The only way to avoid such a situation is to borrow from oneself. The economies where borrowing only from within the locality is possible have public banks of all shapes and sizes. Where this is not possible the situation in Spain as described above gets replicated with “wizards” pulling strings to justify fraud. The fraud is the impossibility of any entity maintaining exponential growth of extracted wealth over many doubling periods. The private entities that govern nonlocal lending seek control of everything by convincing us all that their mining activities are for own good when the fact is the opposite.

This charade has been discussed by Albert Bartlett but he was unsuccessful in dispelling the myth of the possibility of exponential growth of anything occurring over an extended period. This intelligent group is focusing on a small portion of the curve depicted by the formula FV=PV*(1+INTEREST RATE) power of N. Where N is the compounding period. Those who successfully manage large investment portfolios see the whole curve and do everything they can to keep everyone else from understanding how close they are to controlling over half the wealth of the world. This is important because before the last doubling in a finite situation the “pond is only half full”. We live on a finite planet and economists are spinning tales of infinite possibilities. When some group controls everything in a finite situation everyone else has nothing. We are close to this condition and need to learn to think better.

Remember the rule of seventy. Money doubles in ten years at 7%. We do not have long to wait.