Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – August 10, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

People are richer if the government issues bonds to match its net deficit spending relative to a situation where the government just instructed the central bank to ensure all spending cleared the payments system.

The answer is False.

This answer relies on an understanding the banking operations that occur when governments spend and issue debt within a fiat monetary system. That understanding allows us to appreciate what would happen if a sovereign, currency-issuing government (with a flexible exchange rate) ran a budget deficit without issuing debt?

In this situation, like all government spending, the Treasury would credit the reserve accounts held by the commercial bank at the central bank. The commercial bank in question would be where the target of the spending had an account. So the commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a deposit would be made.

The transactions are clear: The commercial bank’s assets rise and its liabilities also increase because a new deposit has been made. Further, the target of the fiscal initiative enjoys increased assets (bank deposit) and net worth (a liability/equity entry on their balance sheet). Taxation does the opposite and so a deficit (spending greater than taxation) means that reserves increase and private net worth increases.

This means that there are likely to be excess reserves in the “cash system” which then raises issues for the central bank about its liquidity management. The aim of the central bank is to “hit” a target interest rate and so it has to ensure that competitive forces in the interbank market do not compromise that target.

When there are excess reserves there is downward pressure on the overnight interest rate (as banks scurry to seek interest-earning opportunities), the central bank then has to sell government bonds to the banks to soak the excess up and maintain liquidity at a level consistent with the target. Some central banks offer a return on overnight reserves which reduces the need to sell debt as a liquidity management operation.

What would happen if there were bond sales? All that happens is that the banks reserves are reduced by the bond sales but this does not reduce the deposits created by the net spending. So net worth is not altered. What is changed is the composition of the asset portfolio held in the non-government sector.

The only difference between the Treasury “borrowing from the central bank” and issuing debt to the private sector is that the central bank has to use different operations to pursue its policy interest rate target. If it debt is not issued to match the deficit then it has to either pay interest on excess reserves (which most central banks are doing now anyway) or let the target rate fall to zero (the Japan solution).

There is no difference to the impact of the deficits on net worth in the non-government sector.

Mainstream economists would say that by draining the reserves, the central bank has reduced the ability of banks to lend which then, via the money multiplier, expands the money supply.

However, the reality is that:

- Building bank reserves does not increase the ability of the banks to lend.

- The money multiplier process so loved by the mainstream does not describe the way in which banks make loans.

- Inflation is caused by aggregate demand growing faster than real output capacity. The reserve position of the banks is not functionally related with that process.

So the banks are able to create as much credit as they can find credit-worthy customers to hold irrespective of the operations that accompany government net spending.

This doesn’t lead to the conclusion that deficits do not carry an inflation risk. All components of aggregate demand carry an inflation risk if they become excessive, which can only be defined in terms of the relation between spending and productive capacity.

It is totally fallacious to think that private placement of debt reduces the inflation risk.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Why history matters

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

- The complacent students sit and listen to some of that

- Saturday Quiz – February 27, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 2:

The sectoral balances perspective of the national accounting framework tells us that the private domestic sector cannot save if a nation’s external sector is in balance and the government runs a balanced budget.

The answer is False.

Read the words correctly. We are asking whether the private domestic sector is unable to generate a flow of saving in a given accounting period when the budget is balanced and the economy is effectively closed (external balance). This is distinct asking whether the private domestic sector is saving overall as a sector, which relates to whether the private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning. The private domestic sector can still be saving (meaning consuming less than disposable income) while still spending more than it is earning.

This is a question about sectoral balances. Skip the derivation if you are familiar with the framework.

First, you need to understand the basic relationship between the sectoral flows and the balances that are derived from them. The flows are derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

Another perspective on the national income accounting is to note that households can use total income (Y) for the following uses:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

You than then bring the two perspectives together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations which allow us to understand the influence of fiscal policy over private sector indebtedness.

So we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total private savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and not matters of opinion.

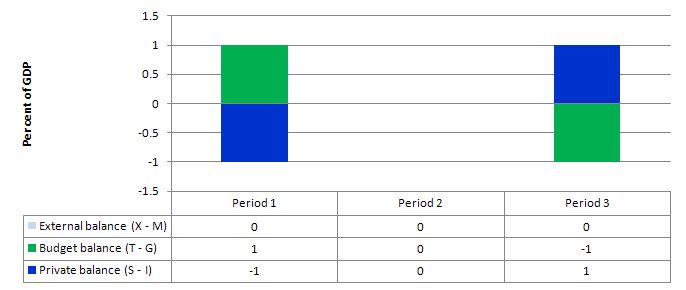

Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance.

Period 1, the budget is in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). This means that the private domestic sector is spending more (via consumption and investment taken together) than it is earning. So it is dissaving overall. Note that households could still be saving (that is, not spending all of their disposable income). But as a sector, the combination of firms and households would be dissaving.

With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector.

In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save (S – I = 1).

Period 2, is the case in point and the sectoral balances show that if the external sector is in balance and the government is able to achieve a fiscal balance, then the private domestic sector must also be in balance. This means that the private domestic sector is spending exactly what they earn and so overall are not saving.

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable and would lead to changes in the other balances as national income changed in response to the decline in private spending.

So under the conditions specified in the question, the private domestic sector cannot save overall. The government would be undermining any desire to save by not providing the fiscal stimulus necessary to increase national output and income so that private households/firms could save overall.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Saturday Quiz – June 19, 2010 – answers and discussion

Question 3:

So-called “progressives” tend to argue that if austerity is to be imposed it is better to increase taxes (particularly on high income earners). Conversely, “conservatives” demand spending cuts and privatisation. In terms of the initial impact on national income, which policy option will be more damaging – a tax increase which aims to increase tax revenue at the current level of national income by $x or a spending cut of $x?

(a) Tax increase

(b) Spending cut

(c) Both will be equivalent

The answer is Spending cut.

The question is only seeking an understanding of the initial drain on the spending stream rather than the fully exhausted multiplied contraction of national income that will result. It is clear that the tax increase increase will have two effects: (a) some initial demand drain; and (b) it reduces the value of the multiplier, other things equal.

We are only interested in the first effect rather than the total effect. But I will give you some insight also into what the two components of the tax result might imply overall when compared to the impact on demand motivated by an decrease in government spending.

To give you a concrete example which will consolidate the understanding of what happens, imagine that the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income is 0.8 and there is only one tax rate set at 0.20. So for every extra dollar that the economy produces the government taxes 20 cents leaving 80 cents in disposable income. In turn, households then consume 0.8 of this 80 cents which means an injection of 64 cents goes into aggregate demand which them multiplies as the initial spending creates income which, in turn, generates more spending and so on.

Government spending cut

A cut in government spending (say of $1000) is what we call an exogenous withdrawal from the aggregate spending stream and this directly reduces aggregate demand by that amount. So it might be the cancellation of a long-standing order for $1000 worth of gadget X. The firm that produces gadget X thus reduces production of the good or service by the fall in orders ($1000) (if they deem the drop in sales to be permanent) and as a result incomes of the productive factors working for and/or used by the firm fall by $1000. So the initial fall in aggregate demand is $1000.

This initial fall in national output and income would then induce a further fall in consumption by 64 cents in the dollar so in Period 2, aggregate demand would decline by $640. Output and income fall further by the same amount to meet this drop in spending. In Period 3, aggregate demand falls by 0.8 x 0.8 x $640 and so on. The induced spending decrease gets smaller and smaller because some of each round of income drop is taxed away, some goes to a decline in imports and some manifests as a decline in saving.

Tax-increase induced contraction

The contraction coming from a tax-cut does not directly impact on the spending stream in the same way as the cut in government spending.

First, imagine the government worked out a tax rise cut that would reduce its initial budget deficit by the same amount as would have been the case if it had cut government spending (so in our example, $1000).

In other words, disposable income at each level of GDP falls initially by $1000. What happens next?

Some of the decline in disposable income manifests as lost saving (20 cents in each dollar that disposable income falls in the example being used). So the lost consumption is equal to the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income times the drop in disposable income (which if the MPC is less than 1 will be lower than the $1000).

In this case the reduction in aggregate demand is $800 rather than $1000 in the case of the cut in government spending.

What happens next depends on the parameters of the macroeconomic system. The multiplied fall in national income may be higher or lower depending on these parameters. But it will never be the case that an initial budget equivalent tax rise will be more damaging to national income than a cut in government spending.

Note in answering this question I am disregarding all the nonsensical notions of Ricardian equivalence that abound among the mainstream doomsayers who have never predicted anything of empirical note! All their predictions come to nought.

You may wish to read the following blogs for more information:

For question 3 is c) the answer in the long term?

I have seen you write the words “cash system” many times when you discuss excess reserves. However, I don’t really understand what you mean when you say that. What does “cash system” mean and if something is not a “cash system,” what is its name ?

So, if I read ” … the private domestic sector cannot save …” as ” … the private sector cannot save overall … “, then I can give myself a correct answer, right?

Dr. Mitchell,

I do not understand the difference between the “private domestic sector” and the “private domestic sector overall”. They seem to be the same to me.

Also, “The private domestic sector can still be saving (meaning consuming less than disposable income) while still spending more than it is earning.” is a problem for me. If I earn 100 and pay tax of 20 my disposable income is 80. If I consume 70, 10 could go to savings or investment. I may not understand exactly what you mean by “spending” but if I spend more than I earn (100), by investing 20, then my spending would be 110, but then I would have to borrow 10, so I would not be saving when I spent more than my income. What am I missing?

“The private domestic sector can still be saving (meaning consuming less than disposable income) while still spending more than it is earning.”

This is perplexing for me too. Can someone explain what this means and give an example with numbers?

Dear Larry Kazdan (at 2013/08/13 at 18:43) and others

TOPIC: Distinction between saving as a sub-sector (Households) and saving overall as a sector (Private Domestic Sector).

Please read the following blog (Answer to Q1) https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=18780

best wishes

bill