At the moment, the UK Chancellor is getting headlines with her tough talk on government…

Questions and Answers 4

This is the Q&A (Part 4) blog where I try to catch up on all the E-mails (and contact form enquiries) I receive from readers who want to know more about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) or challenge a view expressed here. It is also a chance to address some of the comments that have been posted in more detail to clarify matters that seem to be causing confusion. So if you send me a query by any of the means above and don’t immediately see a response look out for the blogs under this category (Q&A) because it is likely it will be addressed in some form here. It is virtually impossible to reply to all the E-mails I get although I try to. While I would like to be able to respond to queries immediately I run out of time each day and I am sorry for that. I plan to make this a regular Friday exercise.

Question 1:

I have read that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) says that a government deficit (surplus) is equivalent to a non-government surplus (deficit). Sometimes this is stated in terms that the non-government sector cannot save overall when the government is running a surplus. Does that mean that when the government runs a surplus that no households can save That seems an unrealistic conclusion when applied to the real world.

It would be an unrealistic conclusion. However, the question conflates two different concepts which are related but not equivalent.

The statement that a government deficit (surplus) is equal to a non-government surplus (deficit) is correct to the last cent because is merely an accounting statement reflecting the way in which the national accounts are derived.

In other words, is true by definition.

However, that statement tells you nothing as it stands about what households are doing with respect to the use of disposable income.

Macroeconomics is the study of behaviour and outcomes at the aggregate level, and in that sense, blurs a lot of detail about what is happening below the aggregate level.

The sectoral balances framework derived from the national accounts is a good starting point. Skip the derivation if you are familiar with the framework.

This framework summarises, in a succint accounting relationship, the basic interactions between the broad sectoral flows in the economy. At the most aggregate, it captures the relationship between the government and non-government sectors. It is sometimes useful to decompose the non-government sector into the private domestic sector and the external sector.

In turn, the private domestic sector is typically disaggregated in macroeconomics textbooks into the household and firm sub-sectors. From behavioural perspective, households consume and save (these are flows) while business firms produce and invest (also flows).

A flow is measured the unit of time, whereas a stock is measured at a point in time. We don’t talk about the “stock” of water flowing from a tap. We express the flow in terms of so many litres per minute or whatever. This water flow can fill up a swimming pool and we would say that at the current time, the pool has X thousand litres of water in it.

Using the three sector model (government, private domestic and external), we consider the spending flows derived from the National Accounting relationship between aggregate spending and income. So:

(1) Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

where Y is GDP (income), C is consumption spending, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is exports and M is imports (so X – M = net exports).

The spending flows perspective (in Equation (1)) highlights the sources of spending (aggregate demand) which drive output and income determination.

We can take another perspective of the national income accounts, by focusing on how the final GDP or income (Y) that is generated by the spending flows is used by households. So:

(2) Y = C + S + T

where S is total saving and T is total taxation (the other variables are as previously defined).

This says that households pay taxation to the government, which then leaves them with disposable income (Y – T) and then they choose to consume. The disposable income that remains after the flow of consumption spending is what macroeconomists call saving.

Going back to the balances, we can bring the two perspectives (sources and uses) together (because they are both just “views” of Y) to write:

(3) C + S + T = Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

You can then drop the C (common on both sides) and you get:

(4) S + T = I + G + (X – M)

Then you can convert this into the familiar sectoral balances accounting relations and we can re-arrange Equation (4) to get the accounting identity for the three sectoral balances – private domestic, government budget and external:

(S – I) = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sectoral balances equation says that total household savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

Another way of saying this is that total household savings (S) is equal to private investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting and are not matters of opinion.

You can see that the non-government sector balances are equal to (S – I) – (X – M). So the framework can be simplified to give the most aggregate statement:

(5) (G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M)

The first term on the right-hand side (S – I) relates to the overall balance of the private domestic sector (not the household sector) and the second term (X – M) relates to whether the net savings of non-residents are positive or negative.

It is clear that if we had a balanced budget (G = T) and an external balance (X = M) then (S – I) = 0.

Does this mean that there is a zero flow of saving in the economy? Definitely not. Households could still be consuming less than their disposable income which means that S > 0. What it means is that the private domestic sector overall is not saving because it is spending as much as it earns.

It also means that when the government is running a balanced budget the non-government sector must be spending exactly what it earns and is not accumulating net financial assets (as a sector). When the external sector is in balance, then that conclusion applies directly to the private domestic sector.

Think about this carefully. Clearly, if households do not consume all their disposable income each period then they are generating a flow of saving. This is quite a different concept to the notion of the private domestic sector (which is the sum of households and firms) saving overall. The latter concept (saving overall) refers to whether the private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning, rather than just the household sector as part of that aggregate.

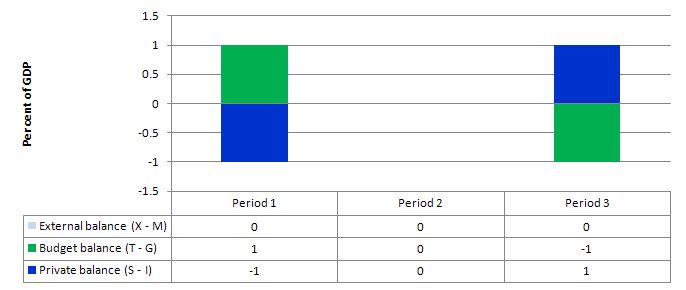

Consider the following graph which shows three situations where the external sector is in balance.

Period 1, the budget is in surplus (T – G = 1) and the private balance is in deficit (S – I = -1). This means that the private domestic sector is spending more (via consumption and investment taken together) than it is earning. So it is dissaving overall. Note that households could still be saving (that is, not spending all of their disposable income). But as a sector, the combination of firms and households would be dissaving.

With the external balance equal to 0, the general rule that the government surplus (deficit) equals the non-government deficit (surplus) applies to the government and the private domestic sector.

In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save overall (S – I = 1).

Period 2, is the case in point and the sectoral balances show that if the external sector is in balance and the government is able to achieve a fiscal balance, then the private domestic sector must also be in balance. This means that the private domestic sector is spending exactly what they earn and so overall are not saving. However, the household sector could still be generating flows of saving (consumption less than disposable income) and this overall condition still hold.

The movements in income associated with the spending and revenue patterns will ensure these balances arise. The problem is that if the private domestic sector desires to save overall then this outcome will be unstable and would lead to changes in the other balances as national income changed in response to the decline in private spending.

I have noticed a lot of angst in questions sent to me about this topic and some suggest that MMT proponents do not understand what saving is.

I hope this answer educates you to a different view about that.

Question 2:

Austerity, is the the dominant mantra in Europe, what does it mean in the context of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)? What is wrong with the original euro design and why?

Fiscal austerity specifically refers to a situation where governments deliberately choose to run discretionary fiscal policy in a pro-cyclical manner.

Remember that the final budget outcome is the sum of the cyclical and discretionary (“structural”) components. Please read my blog – Structural deficits – the great con job! – for more discussion on this point.

So we evaluate the fiscal stance of the government with reference to the structural component of the final budget outcome. Sound fiscal practice would mean that the government choose to ease its discretionary policy (increase spending and/or lower tax rates) when the economy is faltering and vice-versa.

In doing so, the government would be influencing the output (spending) gap created by variations in non-government spending (most typically, private investment spending).

We call this sort of policy activism – counter-stabilisation because it seeks to stabilise aggregate demand in a counter-cyclical manner, where the business cycle fluctuations are being driven by the non-government spending variations.

The government may choose to use fiscal policy to alter the structural mix of final spending (between public and private) but that is a separate issue to that being considered here.

Over a normal business cycle then, the aim of fiscal policy should be to fill any spending gap left by a slowdown in non-government spending or make “spending” room available for observed growth in non-government spending. That is the nature of counter-cyclical policy interventions.

Pro-cyclical interventions are the anathema of sound fiscal policy management, especially if the economy is already full employment or if there is significant unemployment.

In the former case, such interventions involve the government deliberately choosing to push nominal aggregate demand faster than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it. Clearly, this strategy would be inflationary.

When there is unemployment, pro-cyclical fiscal interventions (that is, fiscal austerity) mean that the government is deliberately choosing to widen the output (spending) gap and further undermine the capacity of the economy to grow up a income growth).

There is one situation where pro-cyclical fiscal policy is warranted. At a time when the output gap is significant and unemployment is high, discretionary decisions to expand the budget deficit are sound even if private spending is recovering and economy is growing. An early stages of recovery, when expectations are fragile, fiscal support can help consolidate the optimism associated with the recovery and fast-track the economy back to full employment.

The design of this fiscal support must allow for a withdrawal of the stimulus as the economy reaches full employment and private spending growth is back on track. So policies that entrench more or less permanent changes in the fiscal position are unattractive in this situation relative to short-term stimulus measures, such as, major capital works.

What MMT clearly demonstrates (and this is consistent with Keynesian insights, so is not a new “discovery” of MMT), is that a sovereign, currency-issuing government can always use fiscal policy to fill an existing spending gap and thus maintain high levels of employment.

It is in this sense, that MMT concludes that unemployment above the frictional level is always a policy choice of the national government. If there is mass unemployment then there is only once sector to blame – the government.

However, when we consider the situation of member states of the European Monetary Union (EMU), modifications in the standard MMT conclusion have to be made.

None of the member states in the EMU are sovereign in their own currency – they all use a foreign currency (the euro). That means they have chosen a monetary system which imposes financial constraints on their ability to use fiscal policy to manage cyclical fluctuations in aggregate demand.

All member states in the EMU thus have to raise revenue from taxation and/or bond issuance to cover their spending choices.

As a result, a particular government may find that the public spending necessary to attenuate and output gap in its economy is untenable given its tax base and the terms under which the private bond markets will lend them money.

In a properly designed federal monetary system, this problem (that is, the shortfall in spending capacity) would be resolved by a central fiscal transfer capacity designed to maintain high standards of living across the federated regional space and render this “federal government” capable of meeting the challenges that asymmetric demand shocks place on the federation.

The problem facing member states in the EMU is that the design of the system deliberately excluded this federal fiscal role. It was clear at the time and the Euro bosses wanted to limit the capacity of the states to intervene in economic matters.

Not only did they fail to create this “federal” capacity but they also proceeded to place unrealistically, harsh fiscal rules on the already constrained member states.

The upshot of these design failures is that the member states are now incapable of dealing with events that can severely undermine the prosperity of their citizens.

That is, the design of the EMU means that mass unemployment will be the norm rather than the exception.

The logic of denying the member states of this capacity also leads to the Euro bosses insisting on fiscal austerity as a response to the shortfall in spending that the system, itself, guarantees.

So fiscal austerity in the Eurozone context merely adds another layer of poor practice to an already flawed monetary system design.

I have noted a few papers around attacking MMT on the basis that governments are in fact financially constrained even when they issue their own currency. According to these argumens, proponents of MMT are wrong to claim that currency-issuing governments are not financial constrained.

However, these criticisms miss the mark. MMT proponents continually acknowledge that currency-issuing governments voluntarily create legal and accounting structures, which place restrictions on the way in which they spend and how much they can spend at any point in time.

Just insisting that all government spending is matched $-for-$by privately-placed debt issuance is such a restriction. There are a myriad of such restrictions including accounting rules that say that private money must flow into certain accounts before the government can draw on these funds to facilitate government spending.

But these rules and conventions do not negate the intrinsic characteristics of the non-convertible currency system that the majority of governments run in the present-day. MMT attempts to highlight these intrinsic characteristics so that citizens can understand that the rules and conventions that are put in place “on top of” the monetary system are in fact political rather than financial structures.

The rules hide the essential characteristics of the monetary system. In other words, we attempt to illuminate the political nature of economic policy.

Our contention, is that if the citizenry came to broadly believe that the government cannot run out of money – as an intrinsic matter – then they may deal with the state in a different way and refuse to allow the state to choose policy priorities which undermine the broader welfare of society under the guise of financial constraints.

Further, it is true that the EMU nations have also voluntarily chosen to place financial constraints on themselves. So how is that different to some accounting rule that the US government might have in place which forces it to behave in certain ways when it comes to spending US dollars, which in unambiguously issues under monopoly conditions?

The answer is that for the EMU nations to restore currency sovereignty they would have to abandon their whole monetary system.

For the US government, for example, they already have currency sovereignty and they could legislate to make that more transparent any time they chose.

Please read my blog – On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

You can see that answering these questions takes some time. I am always sorry I cannot respond to each individual request for information but I am trying through this avenue to bring together a number of similar questions and provide a detailed treatment of them.

I have a long list to get through and will keep working away at it as time permits.

But I have run out of time today and have to catch a flight.

Advertising Feature – Pressure Drop comeback show – March 24, 2012

My old band – Pressure Drop – is making a comeback on March 24, 2012 in Melbourne. The band was one of the early pioneers of rock steady, reggae and dub in Australia starting life in Melbourne in 1978. The band was very popular around the pubs and clubs in Melbourne for the next several years. We enjoyed great support across the city and down the surf coast and offered a new sound to the dance and soul crowd in Melbourne. The band also firmly integrated political and economic commentary into its dance set.

We always meant to make a comeback but it has taken 30-odd years to get things in place to do it.

Here is a link to the announcement – Pressure Drop comeback show announced – March 24, 2012.

Here is the poster for the show – you can click it to maximise it.

Australian guitar legend, Ross Hannaford and his band are doing the support starting at 20:40. We are scheduled to start at 21:40.

So if you are in Melbourne tomorrow night and want to come along, it would be good to see you although I doubt I will be too keen to discuss budget deficits or government policy. However, in our modern guise, the band has a multimedia show which contains lots of economic and social commentary.

That is enough for today!

Bill,

On the savings issue, the confusion comes from the definition of saving. You’ve written above:

“In Period 3, the budget is in deficit (T – G = -1) and this provides some demand stimulus in the absence of any impact from the external sector, which allows the private domestic sector to save overall (S – I = 1).”

So saving is defined here as S-I. So what then is ‘S’? If ‘S’ is a positive number, then can’t the private sector be said to be saving overall, regardless of the magnitude of I? If S-I is positive, wouldn’t it be more correct to say that the private domestic sector is saving (net of investment) overall?

I think this is the point that is generating angst, not whether or not households can save while S-I is negative.

Bill,

The question we all want answering is when do you sleep? My theory is that you have a Tardis time machine to fit all you do in. Thank you again for doing so.

Ben

IMO the whole debate about that is kind of blaming MMT that these savings are not real, they are nominal. And the argument has kind of anti government deficit spending bias(may by I am wrong). MMT statement is purely financial.

We cannot conclude that the savings created by government spending are any less ‘real’ than savings created by commercial banks issuing loans or corporations issuing bonds. Government can invest too.

“IMO the whole debate about that is kind of blaming MMT that these savings are not real, they are nominal.”

Which is hilarious since one of the main thrust of MMT is that these excess nominal savings are indeed the problem that needs sorting out – brought about by an endogenous money system that *does not* balance savings and investment over any time period.

“…So saving is defined here as S-I…”

Not exactly. S-I is “saving overall” over the budget cycle, which is different than “saving.”

from SNA: “Net saving is net disposable income less final consumption expenditure”.

Net disposable income is gross income minus taxes. Then:

Saving = Y -T – C; which is not the same as S-I.

If one spends more time understanding closed systems and less time thinking about accounting issues this subject would be much less confusing.

Here is my question.Two questions really. How does one calculate overall savings for the private sector (housholds and firms? I presume it is total household and firm disposable income and profits less consumption.

Now suppose that households and firms in the sector save 100 and the other sectors are in balance. Then assume they manage to, say, put 30 in the bank, buy a share of stock for another 30 and buy a machine for 40 with the overall savings. If, as noted, the other sectors are in balance, then is the entire 100 considered investment? It would seem the math drives one there. But it is hard to believe that a bank deposit and share of stock is the same as buying a machine to, say, make widgets. What am I missing? (maybe that’s three questions.)

I agree with someone else’s comment here. How in the world do you keep up with all your activities and writings?

Your derivation of the sector balance has some implications that rattle my intuition and perhaps that of others.

S and T appear only in the household equation. So, all saving (S) is that of households, and business retained earnings must be something other than saving, I’m not sure what. Likewise taxes (T) are paid by households, and business taxes must be booked as something other than taxes.

The way I rationalize this is to consider that all income goes to and consumption is by households. So, ultimately households pay business taxes through the household cost of consumption. That is, business taxes are costs of production ultimately borne by households. Also, business consumption is investment (I) in the means of production. I think this is consistent with S=I when public and external sectors are balanced.

A rock band too, Bill? Isn’t being an economic genius enough for you? I suppose your other hobbies include walking high-wire across the Olduvai Gorge. Many thanks for all your enlightening blogs! Very much appreciated!

“Likewise taxes (T) are paid by households, and business taxes must be booked as something other than taxes.”

Domestic business taxes are booked to consumption and investment. They are ‘intermediate’ entries. They ‘increase’ the value of consumption. If you think about it all business taxes can be treated as a ‘sales tax’ (and some people advocate doing just that).

Similarly with domestic business savings – which, overall, must come from the profits earned from money spent by consumers, government or invested by other businesses. So you don’t need to count it again in a three sector model.

Spending is a cycle and the national accounts people ‘tap’ the cycle at the point of the household, which they define as ‘final’ spending.

Because everything is inter-related it works doing it like that. But it does take a bit of getting your head around and it helps to think in circles and cycles.

Dear Bill, your blog is simply great! Thank you very much indeed for that. Just one question: You say twice that “net exports represent the net savings of non-residents.” It seems to me that this is not correct. Net exports mean that the residents of a country “give up” part of their production, i. e. they do not consume all that they have produced, but save instead and let foreigners consume part of their production. So I think net exports represent net savings of residents rather than non-residents!

Thank you Neil. Your explanation makes sense and is very helpful.

Neil, you have me confused. Can you expand on your comment that: ” Domestic business taxes are booked to consumption and investment. They are ‘intermediate’ entries. ” Do you mean to say that corporate taxes and sales taxes are included in C, consumption expenditures? Or are they subtracted out and reported seperately in the final tally? When they book taxes, do they count them the way corporations do, ie include deferred taxes?

The more I read this the more confused I get.

So essentially we are saying that private household savings can fund business investment, however, if the external sector is in deficit, (US) then the government must run deficits in order to provide long-term growth, since eventually the investment will not be able to be maintained i.e. late 1990s in the US without infusion of money from the government sector. Does any of what I’m saying make sense? Thanks to the smart people on this board 🙂

“Do you mean to say that corporate taxes and sales taxes are included in C, consumption expenditures? ”

Business taxes and sales taxes are included in the end price of stuff and services, so part of ‘T’ represents them. ‘T’ isn’t just the taxes you pay personally with a cheque – its all transfers to the government sector, direct or indirect, from household income.

‘S’ is not just household saving, but domestic Gross Savings ie all the savings in the domestic private sector, direct or indirect.

‘C’ is Household Final Consumption, which excludes everybody’s savings and everybody’s taxes in the domestic private sector.

So whenever you spend on anything you can look at the price and it will always be composed of ‘C+S+T’ in some proportion. You’re always paying taxes somebody else has remitted to the government and you’re always funding somebody else’s savings as well as buying the item in question.

Thanks for that Neil. So it turns out C is not as simple as it looks. Somehow they extract all the taxes in the things we buy. So here is another one for you. If you look at GDP for the fourth quarter (table 1.1.5) it says personal consumption expenditures were 10.9 trillion. Is that C or are there adjustments that need to be made to it, like exports and imports?

It would be great if someone could actually put up a blog on how the equations are derived.

jonf,

I did that for the UK and if bill will approve the links they are:

Reconciling S = I + (S – I) to the national accounts (Wonky)

and

Savings – Explaining the Humpty Dumpty word

both of which show how the National Account language resolves to MMT’s terms.

“It is clear that if we had a balanced budget (G = T) and an external balance (X = M) then (S – I) = 0.”

I’m pretty sure you are assuming all new medium of account/medium of exchange (MOA/MOE) are borrowed into existence. If that assumption is junked, is it possible there is an entity missing in CA deficit = gov’t deficit plus private deficit?