I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

It is hard to defend the 1 per cent by claiming their contribution added value

Writer of popular textbooks on macroeconomic myths, N. Gregory Mankiw has just put out a paper – Defending the One Percent – which is due for publication in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. The paper presents a narrative about the shift in the US personal income distribution (sharply towards higher inequality) since the 1970s in terms of rewards forthcoming to exceptionally skilled entrepreneurs who have exploited technological developments to provide commensurate added value (welfare) to all of us. As a result, rewards reflect contributions and so why is that a problem? In other words, the “left” (as he calls the critics of the rising inequality) are wrong and are in denial of reality. That view is unsustainable when the evidence is combined with a broad understanding of the research literature. Ability explains the tiniest proportion of the movements in income distribution. Social power and class, ignored by the mainstream economics approach, provides a more reliable starting point to understanding the rising inequality.

Before we begin there was an interesting statement from the Japanese Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister a few days ago (June 17, 2013) – 国の借金「刷って返せばいい」=財政ファイナンスを容認? ―麻生財務相.

He was speaking in Yokohama on how despite having the largest public debt/GDP ratio among advanced nations the bond markets are no problem and inflationary expectations are falling.

My source (Thanks JJ Lando) indicated that his presentation style was emphatic – along the lines of – get with the program you idiots this is our currency we are talking about and we issue it.

The translation of the news item linked to above courtesy of Scott McClean in Japan is as follows:

Taro Aso commented on the problem of Japan’s ballooning national debt in a speech on June 17 in Yokohama. “Japan issues debt (bonds) in its own currency. It should print (notes) and pay down the debt. It would be easy, I reckon.”

His comment caused a commotion in the venue, as it was reminder of “public finance,” which pays down fiscal deficits through issuing of currency from the Bank of Japan, which is prohibited under the Finance Law.

“If confidence withers after issuing and excessive amount of money, the interest rates would rise,” Aso said, highlighting the sense of resistance over unlimited money issuing. “Japan’s debt has swelled to 970 trillion yen, yet interest rates haven’t risen. Japan is not in danger of an economic collapse,” he said.

Not much to worry about there. The second part of his statement that yields rise if prices fall is obvious. If people refuse to buy public bonds then yields will rise. That just means that if it really became a problem for real prosperity the Japanese government like all currency-issuing governments could just manage the rates along the curve by buying as much of the debt themselves as required.

Obviously, they could just stop issuing debt altogether and take the “easy” (and most sensible option) as the Minister identified.

The – Journal of Economic Perspectives – is published by the American Economic Association (the cartel of mainstream economists, which attempts to control the profession – that is another story). It claims its mission is “to fill a gap between the general interest press and most other academic economics journals”. It thus attempts “to offer readers an accessible source for state-of-the-art economic thinking” etc.

The articles are “normally solicited by the editors and associate editors”, which means it is now a normal submit and referee-type publication.

For a different perspective on the Mankiw article please read – Meet America’s Most Shameless Defender of the 1 Percent, Harvard Economist Greg Mankiw.

I largely agree with the sentiment of that article but I think the personal angle taken by the author doesn’t allow her to get to the bottom of some of the conceptual flaws in Mankiw’s paper.

Here are some observations on Mankiw’s paper, which do not constitute a full attack (especially on his later discussion about philosophy) because I do not have time today.

First, Mankiw’s opening salvo (which is fairly critiqued in the Naked Capitalism article) presumes to justify the highly skewed size distribution of income in terms of just rewards for ability.

There are two concepts of – income distribution – that economists consider.

First, the so-called size distribution of income or personal income distribution, which focuses on distribution of income across households or individuals. Often the data is expressed in percentiles (each 1 per cent from bottom to top), deciles (ten groups each representing 10 per cent of the total income), quintiles (five groups each representing 20 per cent of the total income) or quartiles (self-explanatory).

Various summary measures are used to demonstrate the income inequality. For example, the share of the top 10 per cent to the bottom 10 per cent. The Gini coefficient is another summary measure used in this type of analysis.

Second, the functional distribution of income or the factor shares approach, which divides national income up by what economists call the broad claimants on production – the so-called “factors of production” – labour, capital, and rent. Other classifications also include government given it stakes a claim on production when it taxes and provides subsidies (a negative claim).

This academic article (from 1954) – Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning – is a good starting point for understanding the two concepts in more detail, although you need a JSTOR library subscription to access it.

[Full Reference: G. Garvy (1954) ‘Functional and Size Distributions of Income and Their Meaning’, The American Economic Review, 44(2), Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-sixth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1954), 236-253]

Mankiw’s example assumes at the outset that “people earn the value of their marginal product”. Well not in the real world they don’t?

Consistent with that long discredited model, we are led to believe that there is some pure construct – the laws of demand and supply – over which “institutional arrangements” such as legal structures, unions, concepts of value, etc – are ephemeral complications – nuisances that served no useful economic function and which should be abandoned.

This is a common view propagated by textbook-driven economists. They view the intrinsic social institutions that have developed over the course of history and which define a sophisticated society as being distortions that complicate the purity of the “market”. This view is, of-course, a fiction.

They also assume away other real world complications such as – industry concentration, firm size, conspiracies, illegal behaviour etc.

The Global Financial Crisis has demonstrated categorically that the notion of a self-regulating market is a myth and that market behaviour always needs regulative oversight, which includes the provisions of working conditions that protect the weak, which would otherwise be shed by the employers in seek of even greater profit.

But even if we wanted to play the textbook game, the evidence is not supportive of the major predictions forthcoming from that model, upon which the author has relied to make the case for the employer groups.

Marginal productivity theory is only applicable to highly stylised conditions such as homogeneous labour, perfect competition, and perfect mobility of labour, stable rates of interest, rent and specified prices of the goods. The static nature of the theory is negated by the fact that all the productive factors that are assumed to be constant are in fact constantly changing.

Further, the the famous Cambridge Controversies in the 1960s demonstrated the theory is logically inconsistent (even if we accepted that the real world was akin to the highly stylised world which the theory assumes). This criticism relates to the fact that when there is heterogeneous capital interacting with labour it is impossible to derive a marginal product independent of the price it is seeking to explain. Once we accept that point, the whole theory of distribution that Mankiw uses to drive his example becomes discredited.

The conclusion, now ignored by the mainstream economists like Mankiw is that marginal productivity theory is incapable of providing a logical theory of distribution because there is indeterminacy with the definition of capital.

To measure the capital stock, one had to have prior knowledge of the rate of profit (given the heterogeneity of capital goods). As a result, what is meant in the theory to be the result of the marginal product of capital is dependent on the rate of profit being known, which, in turn, requires that the wage rates are known.

In other words, this circularity means that the distribution of income is not caused by the input contributions as asserted by the theory, which Mankiw’s argument relies upon.

The Cambridge Debates are a classic example of the internal inconsistency of the orthodox approach being exposed yet ignored by the mainstream. They just kept on blithely teaching the same stuff and after a while the memories of the debates (in the 1960s) fade and a generation disappears and so no-one is the wiser.

But we can take the critique further.

A major practical criticism of the theory relates to the fact that there is no meaningful way to separate the contributions of productive factors to total product.

The concept of the marginal product of labour hinges on the preposition “of”, which as J. Pullen noted (Pages 5-6):

… in accordance with some past critics of the MPTD, the thesis being presented here is that the use of “of” in an exclusive sole-proprietor sense in the expression “marginal product of labour” is neither logically, nor linguistically, nor ethically justified, because the marginal product that occurs after the employment of an extra unit of labour (with other factors held constant) does not occur solely because of that extra unit of labour. It occurs because of the combined effect of the extra unit of the variable factor acting together with the factor or factors held constant. It is a multicausal phenomenon rather than a monocausal phenomenon.

[Reference: Pullen, J. (2001) ‘A Linguistic Analysis of the Marginal Productivity Theory of Distribution; or, the use and abuse of the proprietorial “of””, Working Paper Series in Economics, No. 2001-4, February, University of New England]

In 1900, the famous economist J.A. Hobson wrote that marginal productivity theory fails because it presents “… a false separatism … which ignores the organic unity in a business”. Not a lot has changed since then.

[Reference: Hobson, J.A. (1972) The economics of distribution, (Clifton, N.J., Augustus M. Kelley), 1972 reprint, page 144]

There was a fascinating discussion of this problem in a 1914-15 article by W.M. Adriance. He asked in relation to a lumberjack performing his/her work “what fraction of the work is done by the man and what fraction by the ax (sic)” (page 157). His article also brought the concept of co-operation and teamwork into the debate, which, of-course, is ignored in the mainstream microeconomics textbook theory.

[Reference: Adriance, W.M. (1914-15) ‘Specific Productivity’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 29, 149-76]

The technical aspects of the theory require that the partial derivative of output with respect to labour, which is the mathematical equivalent of the marginal product of labour and the corresponding derivatives for the other productive inputs be calculated.

The problems with computing these derivatives (to represent the exact and exclusive productive contributions of the inputs) is that if we cannot conceptually isolate labour as a unique variable input into the production process and assume that nothing else varies when output rises, then this calculus fails to achieve its goal.

So we conclude that the circularity in marginal productivity theory means it cannot be a deterministic explanation of the size distribution of income.

This issue came up in a recent industrial case at which I provided expert testimony on behalf of the unions who were defending employer claims to cut the wages in the restaurants industry.

The employers had dragged out an economist who relied solely on marginal productivity theory to claim that wages should be deregulated in the sector.

He claimed that if you wanted higher employment in the sector, the real wage had to be cut, because the economy was subject to the law of diminishing returns (marginal product of labour declines as more labour is added to other fixed inputs).

His example was that the given the “size of the restaurant, number of cash registers, tables etc remain fixed each successive employee hired (or extra hour worked) will result in a lower increase in output than the one before”.

Any reasonable person (that is, one free of the nonsensical jargon of economics) would find it hard to take this conceptualisation of the flow of work in a food services operation seriously.

In fact, the café environment is more akin to what economists refer to a “fixed factor proportions” model, which is the antithesis of the diminishing returns concept.

Accordingly, there is a given ratio of chefs who can work a given stove area and the management wouldn’t think of adding more than the feasible and safe number. There are a given number of preparation staff to each chef and a given number of waiting staff who can feasibly serve a given number of tables. A firm is not about to add more waiters to stumble over each if the wages for waiters fell.

It is hard to imagine how we could apply marginal productivity theory to a café or restaurant. It requires us to be able to define accurately (and measure) a marginal product for the cafe worker.

How would we do that, given that the operation is a team-based output model? How would a firm go about decomposing the output of a “meal” between the owner, the chef, the kitchen hands, the concierge, the waiter etc?

What would a café or restaurant do, for example, if the hourly wage of the waiter was cut by X per cent? The marginal productivity theory predicts two things would happen: (a) As long as the X per cent cut is greater than the next decrement in marginal productivity the restaurant will engage more waiters; and (b) By adding extra workers each one hired will be less productive than the last.

Imagine we kept cutting the wage to keep it equal to the “marginal productivity” of the succession of next workers that are standing in line waiting for a job. Imagine we only have a small cafe that has say 10 tables to serve. The marginal productivity theory tells us that eventually the firm will have waiters falling over each other, dropping food on customers, as the diminishing returns set in at the lower wage rates.

Clearly that is not even a remotely adequate description of what cafes do or would do. They typically have a set ratio of waiters scaled to serve the tables in their room in some acceptable time frame to ensure customer service.

Cutting the wage of those waiters will not lead the cafe to hire more waiters – it would only mean they will make more profit per waiter assuming the quantity (and quality) of the waiting staff would tolerate the cut in wages.

This set ratio is what we call “fixed factor coefficients”. To expand the business, the cafe will need to add more tables to accommodate hiring more waiters.

The mainstream will claim that lower wages will lead firms to open on occasions they currently find it unprofitable to open. However, even if that was true, the scale of the business would be changing and the law of diminishing returns only applies to a fixed scale with one variable input.

Once we start arguing that the scale of all inputs alters then the law of diminishing returns becomes irrelevant even in neoclassical theory.

It is obvious that firms will employ more people if they have the scale to expand and it is profitable to do so. If they exhaust their scale (that is, their existing capacity) and nominal demand for their product or service increases they will either invest in new capacity (a larger restaurant or a chain of restaurants or open more days).

There are two crucial requirements though: (a) that the extra output can be sold; and (b) that the firm can attract the necessary labour (and other) inputs to accommodate the increase in scale.

Imagine that no cafe operates at the weekend at present and all cafes are serving up to full capacity each time they open? Now, imagine that wages are cut and firms suddenly expanded output.

Where will the extra demand come to justify the extra hours of operation? Just because the firm can make more profit (assuming no negative productivity response from the worker – which in real life we cannot do) this doesn’t mean that there is a commensurate increase in demand for cafe services. Supply doesn’t create demand. It is the other way around.

The mainstream invoke notions of pent up unsatisfied demand for a particular service that firms are not meeting because the wage costs militate against their expansion. So why doesn’t a rival firm meet that demand and take market share?

Anyway, Mankiw then claims that an exceptional entrepreneur comes along, disturbs his initial equilibrium (of equality) and eventually, because everybody recognises this exceptional skill (ability) and buys the products offered, the income distribution becomes highly skewed.

In terms of the radical shift in the distribution of income to the top 1 per cent in the US over the last 40 years, this is just what Mankiw thinks:

… has happened to US society over the past several decades.

He thinks developments in technology have allowed these exceptionally skilled characters (he names the late Steve Jobs by way of example) “to command superstar incomes in ways that were not possible a generation ago”.

Well that is not according to the research evidence from those who have specialised in understanding the size distribution of income – a topic not at the top of Mankiw’s previous academic research work.

Economists who study the personal (size) distribution of income consider the following factors (in no particular order):

1. Ability – innate capacity

2. Human capital – education – augmenting (1) via knowledge and skill accumulation.

3. Stochastic happenings – that is, luck.

4. Individual choice – emphasised by mainstream economists – allegedly, low-paid workers opt to take easier options and high-paid workers invest and eschew short-term gains for longer-term rewards etc.

5. Inheritance – perpetuation of dynasties.

6. Life-cycle – poor when young, rich when accumulation phase is over.

7. Class and power – creating opportunities through social and wealth networks etc.

8. Race and discrimination – sorting those who get opportunities by non-economic factors and ignoring individual capacities.

9. Public policy – how government spending and taxing can alter market outcomes.

These areas of study overlap and are, in some cases, interdependent. For example, individual choice underpins orthodox human capital theory.

The mainstream approach tends to ignore 5, 7 and 8, which in the empirical work seem to be dominant factors explaining income inequality.

The standard economic theory approach fails to explain very much of real world income distributions. Social theory explains much more of the variation.

Granovetter (the sociologist who has advanced our understanding of social networks) refers to neo-classical individuals as being “atomized” (that is, highly independent) and “undersocialized” (that is, not t all interdependent).

This ignores the role of social norms, habits, customs, social place (rank etc). Individuals operate according to group norms and behaviour within groups is highly interdependent.

All this means that individual behaviour is not likely to be dominated by an isolated sense of “self-interest”. We are irrational and social beings and our behaviour is better described by the way that our choices are limited by our milieu than the mainstream approach which considers we maximise from all the choices available.

Further there is social polarisation within our societies with extremely limited mobility between groups across the income distribution. The most talented person (innate) from a poor household rarely has any defined pathways to make it to the top of the distribution.

Where one is born, who one is born to are stronger predictors of outcome than measures of innate talent. The distribution of abilities is not remotely like the final distribution of income.

Clearly, those at the top end of the income distribution are typically better educated than those at the bottom. But access to education is highly filtered by class and background. Our higher educational institutions do not exhibit broad participation across the income distribution.

Public policy (equity programs etc) can alter that somewhat. But education remains a pathway that is embedded in the class society – access is highly unequal and conditional on early childhood outcomes. There is massive intergenerational disadvantage that provides a very reliable predictor for an individual’s outcomes later in life. Most of the poor, stay poor.

Mankiw criticises the 2012 conjecture by Joseph Stiglitz that “rent-seeking is a primary driving force behind the growing incomes of the rich”. He concludes:

There is no good reason to believe that rent-seeking by the rich is more pervasive today than it was in the 1970s, when the income share of the top 1 percent was much lower than it is today.

Hello out there! Neo-liberalism calling.

While I also do not fully agree with Stiglitz’s argument (in The Price of Inequality) there is a lot to be said for his approach relative to trying to explain the shifts in inequality through pure market rewards for talent.

Mankiw focuses on the finance industry “where many hefty compensation packages can be found”. However, he considers these rewards from contribution:

On the one hand, there is no doubt that this sector plays a crucial role. Those who work in commercial banks, investment banks, hedge funds and other financial firms are in charge of allocating capital and risk, as well as providing liquidity. They decide, in a decentralized and competitive way, which firms and industries need to shrink and which will be encouraged to grow. It makes sense that a nation would allocate many of its most talented and thus highly compensated individuals to this activity. On the other hand, some of what occurs in financial firms does smack of rent seeking: when a high-frequency trader figures out a way to respond to news a fraction of a second faster than his competitor, his vast personal reward may well exceed the social value of what he is producing.

The argument hinges on the “some” proportion.

Please read my blog – Financial markets are mostly unproductive – for more discussion on this point.

Take banking, for example. The impact of the collapse of many banks in recent years on the real economy has been devastating. The fact that recessions derived from financial collapse last longer and are deeper than real-economy-based downturns adds to the damage.

How large the losses will be of the behaviour of the financial sector is anyone’s guess at present. Massive at least.

What about the “good times”? Does the financial sector contribute enough to the real economy to explain the massive shift in real incomes taken out by the financial market executives?

There is no doubt that the contribution of banking (intermediation) is overstated in national accounting measures. The crisis has demonstrated that all those allocators “of capital and risk” were not doing a very good job.

A 2011 Voxeu article, written by two Bank of England officers – What is the contribution of the financial sector? – noted that:

High pre-crisis returns in the financial sector proved temporary … Many financial institutions around the world found themselves calling on the authorities, in enormous size, to help manage their solvency and liquidity risk. That fall from grace, and the resulting ballooning of risk, sits uneasily with a pre-crisis story of a shift in the technological frontier of banks’ risk management.

In fact, high pre-crisis returns to banking … reflected simply increased risk-taking across the sector. This was not an outward shift in the portfolio possibility set of finance. Instead, it was a traverse up the high-wire of risk and return. This hire-wire act involved, on the asset side, rapid credit expansion, often through the development of poorly understood financial instruments. On the liability side, this ballooning balance sheet was financed using risky leverage, often at short maturities.

And was that increased risk taking (which was accompanied by the increasing skew in the income distribution) productive?

The Voxeu article says there is no value-adding role forthcoming from this sort of behaviour, which has dominated the growth of the financial sector.

The authors say that “bearing risk is not, by itself, a productive activity”.

They claim that the “management of risk” is productive. Yet, the crisis demonstrated that a substantial portion of the increased risk was “mis-priced or mis-managed”.

Accordingly:

… a banking system that does not accurately assess and price risk could even be thought to subtract value from the economy

And to make the point clear they tell us “If risk-making were a value-adding activity, Russian roulette players would contribute disproportionately to global welfare”.

The Rolling Stone article from July 9, 2009 – The Great American Bubble Machine – is a good introduction to the way hedge funds operate.

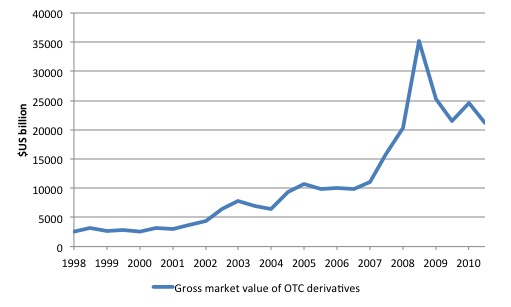

In 2009, the WIFO (Austrian Institute for Economic Research) Report – A General Financial Transaction Tax: A Short Cut of the Pros, the Cons and a Proposal – outlined the explosion of global financial flows and derivative markets in recent decades.

WIFO describe this dominance as follows:

Observation 1: The volume of financial transactions in the global economy is 73.5 times higher than nominal world GDP, in 1990 this ratio amounted to “only” 15.3. Spot transactions of stocks, bonds and foreign exchange have expanded roughly in tandem with nominal world GDP. Hence, the overall increase in financial trading is exclusively due to the spectacular boom of the derivatives markets …

Observation 2: Futures and options trading on exchanges has expanded much stronger since 2000 than OTC transactions (the latter are the exclusive domain of professionals). In 2007, transaction volume of exchange-traded derivatives was 42.1 times higher than world GDP, the respective ratio of OTC transactions was 23.5% …

In other words, most of the financial flows comprise wealth-shuffling speculation transactions which have nothing to do with the facilitation of trade in real goods and services across national boundaries. This is significant and conditions what my conclusions are later.

Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets became increasingly dominant in overall trading as the financial markets grew. Unlike options contracts, OTC contracts are non-standardised and are negotiated on a party by party basis. Forward contracts and swaps are generally OTC. They are more customised and less liquid.

If we compare the BIS estimate of “Amounts outstanding of over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives” in December 2010 – $US 601.048.366 trillion – to the World Bank estimate of World GDP for 2010 (published in the BIS since mid-1998 in $US billions.

This was the period where the income distributions around the started becoming more unequal. While Mankiw claims “There is no good reason to believe that rent-seeking by the rich is more pervasive today than it was in the 1970s”, these developments tell us otherwise.

Financial deregulation created the massive rise in the financial sector. That deregulation was the product of constant lobbying by those who wanted to increase their rents (which are unproductive).

What about foreign exchange transactions? This BIS publication (December 13, 2010) – The $4 trillion question: what explains FX growth since the 2007 survey? – provided a useful analysis of the relationship between foreign exchange turnover and international trade.

It concluded that:

FX turnover is several times larger than the total output of the economy … The FX turnover/GDP ratio is smallest for the largest economies, the United States and Japan. In these two countries, FX turnover is more than 14 times GDP. In most cases … FX market turnover is many times larger than equity trading volumes. Again, the ratio of FX turnover to equity turnover is smallest for the United States and Japan, but still sizeable …

Gross trade flows are defined as the sum of imports and exports of goods and services. FX turnover is much higher than underlying trade flows …

Overall, looking at developments since 1992, it is clear that FX turnover has increased more than underlying economic activity, whether measured by GDP, equity turnover or gross trade flows.

Wall Street used to be about providing capital for productive businesses. So a firm would sell shares or issue corporate paper (bonds) and Wall Street would facilitate the capital provision. That was a productive activity. Clearly, speculators (investors) would bet on the company making returns which was the incentive to participate in its ownership.

Wall Street (and I am using this term as a general description of the financial markets rather than some geographically-specific set of firms) no longer serves that purpose. Now it is a wealth-shuffling casino.

The trading in derivative products of increasing complexity is divorced from the capital-provision function that the investment banks used to play. The focus is not on the prospects of the firm but on macro issues – how stable is the currency etc.

On top of that minor changes in macro aggregates (growth, etc) trigger automated trading decisions which quickly diffuse through all the share and index prices. So the share prices of a specific firm become hostage to the casino.

Some would suggest that providing capital for firms constitutes a miniscule percentage of the volume of Wall Street transactions.

Wall Street does not create jobs or prosperity for the wider population. When we talk about “investors” on Wall Street this is a grand misnomer. They are not investing in productive capacity.

The question that has to be answered is why would we want to allow destabilising financial flows anyway? If they are not facilitating the production and movement of real goods and services what public purpose do they serve?

It is clear they have made a small number of people fabulously wealthy. It is also clear that they have damaged the prospects for disadvantaged workers in many less developed countries.

More obvious to all of us now, when the system comes unstuck through the complexity of these transactions and the impossibility of correctly pricing risk, the real economies across the globe suffer. The consequences have been devastating in terms of lost employment and income and lost wealth.

There is no public purpose being served by allowing these trades to occur even if the imposition of the Tobin Tax (or something like it) might deter some of the volatility in exchange rates.

Conclusion

The personal attacks on Mankiw in the Naked Capitalism article, while apposite are of less interest to me than his on-going insistence that the mainstream theory framework has explanatory value.

I obviously think it does not.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill,

The link to the Mankiw paper in the first paragraph is not working

Cheers

Andi

Your description of foreign currency derivatives is not accurate. Forward contracts are easy to mark-to-market and credit exposures can be substantially mitigated through collateral management where appropriate. Losses on foreign exchange derivatives were negligible in the context of overall losses over the period of the banking collapse.

The growth of derivatives (specifically credit derivatives and related forms of traded structured credit) played a critical role in banking failure, but the reasons why this mattered are not the ones you describe.

Otherwise, good post!

Dear Andi

I have fixed it now. Thanks for the scrutiny.

best wishes

bill

President Obama/Council of Economic Advisers:

In his speech in Berlin, today [6/19/13] President Obama reasserted his belief, and the belief of 86% of Americans, that “anybody willing to work should be able to find a job”.

The question is “How do we get there”?

And this is where “belief” plays a pivotal role….

Building a ship to go around the world never even occurred to a person who believed the world was flat….the concept was beyond their consciousness level-the thought never entered their mind….

And the same situation is true for virtually every Republican in Congress, and unfortunately far too many Democrats: They believe, really believe-that the Market can create enough jobs, so that everyone will have a job….

And when a person believes this, really believes this, it is beyond their consciousness level to even think of a solution to our unemployment crisis-except via the Market creating these jobs….

And this is where “magical thinking” comes into the mix—that is, in spite of 25 million Americans unemployed/underemployed-and the CBO projecting that it will be 2017, on our current path, before we can back to even an anemic 5.5% unemployment—and benefits long since expired-these folks are standing on one foot, and then the other-convinced that the Market can fix this crisis!

In short, even in the face of overwhelming evidence we are on the wrong path to fix this crisis-and the warning sign “Bridge Out Ahead”–their belief prevents them from thinking otherwise!

As proof-on an almost daily basis Boehner blathers on that the Republicans are about “jobs”, but all you have to do is drill down a millimeter and you will find that he means via the above “magical thinking”, i.e., via the “Market”-he is incapable of thinking otherwise!

Ideally, the Market would provide a job to anyone who wants one-The market thrives when we have a robust, employed, consuming workforce-and what is missing is that our current path UNDERMINES THE MARKET!

That is, while claiming to be the Pro-Market Party-the above mind-set makes the Republicans [and like-minded] a hazard to capitalism!

Coming full circle, we need Pro-Market, deficit-neutral: Neighbor-To-Neighbor Job Creation Act: A federally mandated Social Insurance, owned by our employed to provide a fund to hire/train our unemployed. For a modest 4% of salary policy cost, we can reduce our unemployment to 3% within a year of passage.

Please see: ECONOMIC INCLUSIVISM, on Amazon/Kindle

Jim Green, Democrat opponent to Lamar Smith, 2000

Some Guy who likes to provide free links for the indolent and impecunious says:

With bunches of links and formats from archive.org:

Adriance, W.M. , Specific Productivity

Hobson, J.A. , The Economics of Distribution

and

Pullen, J. (2001) ‘A Linguistic Analysis of the Marginal Productivity Theory of Distribution

The system explained by Damon Vrabel.

The problem I have with MMT ?

You want us to work for this ?

Thats sick……pushing resources even further upwards in a extreme Hamiltonian fashion.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3Is0iwTMGE

People losing value as they become unemployable over time loses some money for the owners. (although they have accumulated so much wealth they can afford to burn through people on a massive scale for a long long time)

However at least Its a type of economic harikari with some honour as you rub yourself out from the satanic debt system.

“so what do you do ? ”

I intend to do nothing.

Some Guy

Great links! I’d hug you if you were here.

I suppose there’s not a chance in hell to find a preprint of Garvy, right?

A simple argument against the idea that income distribution is related (in a fair, ie, linear way) to productive individual abilities emerges from the observation that (at least top) income distribution follows a power function.

Yet there is no evident reason to assume that productive abilities are not Gaussian distributed. And a Gaussian distribution of productive abilities does not translate into a fair power function distribution of income. In this view, other factors than productive ability must be operating.

Successful cooperative enterprises present a top to bottom income ratio of 6:1, not 1000:1.

Yes, it’s hard to defend arbitrary distortions of asset allocations. It’s a tough job, so they’ll hire fools to do it.

Then the bulk of us get distracted calling the fools fools.

Classic divide and conquer strategy.

It’s referred to as the “Straw Mankiw” gambit I believe. Named after some ancient disguised chess move.

Greg Mankiw, bought and suborned, enemy of the people, enemy of empirical research. Sentence; shall teach his own textbooks to an empty classroom for the remaining term of his natural life. Next case.

When he says that there is no reason to believe that there is more rent seeking now than before I think he is missing the point. People seek rent using the wealth they have accumulated to date. Unequal wealth distribution allows unequal gathering of rent. Wealth distribution was rebooted back down to relatively even thanks to the waste and destruction of WWII and the high progressive taxes of the post war period. Since then private wealth has been accumulating. Much of the inequality in income is merely due to return on capital and reflects the phenomenal level of wealth inequality. It is a positive feedback loop that widens inequality over time. I’m sorry to bring this up again but MMT prescriptions for endless deficit spending amount to yet more accumulation of private wealth and so ever more dramatically unequal distributions of investment income.

Ole Peters’s “time for a change” video also gives a wonderful illustration of how stochastic effects create widening inequality over time.

I’ve found something I agree with Mankiw on!

“The last thing we need is for the next Steve Jobs to forgo Silicon Valley in order to join the high-frequency traders on Wall Street. That is, we shouldn’t be concerned about the next Steve Jobs striking it rich, but we want to make sure he strikes it rich in a socially productive way.”

So who DOESN’T see HFT as a parasitic distortion??? Why is HFT happening if even Mankiw sees it as rotten???

The political power of finance is built on the size of the stock of net financial assets and that is what has to cut back down to being proportional to the real economy if we want to cure this.

I’m totally staggered that Mankiw thinks that he can write that essay and not address the issue of income from ownership rather than labour. The entire premise of Mankiw’s essay is that income always comes from labour provided and not from capital owned. He even mentions that Warren Buffet gets the bulk of his income from dividends and then blithely ignores that elephant in the room! Doesn’t he care that his omission makes him appear an imbecile???

Mankiw says,”Those who work in commercial banks, investment banks, hedge funds

and other financial firms are in charge of allocating capital and risk, as well as providing

liquidity. They decide, in a decentralized and competitive way, which firms and industries need

to shrink and which will be encouraged to grow. It makes sense that a nation would allocate

many of its most talented and thus highly compensated individuals to this activity.”

Is there really such an effect? I thought the vast bulk of investment by firms was funded using their retained earnings. Do financial markets influence that significantly? If a firm envisions that it can profitably meet expected demand by reinvesting earnings then surely it will do so irrespective of what the stock market does to the stock price???

I suppose in extreme asset bubble situations, phony companies get created and floated on the stock exchange to tap into gullability but doesn’t that only happen at extreme times such as the 1999 stock bubble?