I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Financial markets are mostly unproductive

Today I was reading some academic articles on the implications of budget deficits. In general, the amount of effort that goes into these articles doesn’t match the quality of the argument. They all have predictable formats – some proposition, then invoke neo-classical assumptions, do some mathematics (mostly second-rate in quality), then make a conclusion that was given anyway by the structure of the exercise. As a consequence there is no information content at all in these articles. Just gymnastic exercises. However, one article I read presented a new slant on the case against government spending. It also resonated with my reaction to the release of a major report on executive salaries in Australia today, which quashed hopes that shareholders would have more say in disciplining the companies they own. The debate generalises and points to the conclusion that financial markets are mostly unproductive and have conned us into thinking otherwise.

The Productivity Commission released its report into Executive Remuneration in Australia today (January 4, 2009) and already it looks like they are recommending a soft-line on what our Prime Minister had described as the “obscene executive salary” problem.

For non-Australian readers, the Productivity Commission used to be the Tariffs Board then the Industries Assistance Commission and describes itself as:

The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s independent research and advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of Australians. Its role, expressed simply, is to help governments make better policies in the long term interest of the Australian community.

As its name implies, the Commission’s focus is on ways of achieving a more productive economy – the key to higher living standards. As an advisory body, its influence depends on the power of its arguments and the efficacy of its public processes.

You learn from its history that is was formed in 1998 by the previous conservative government who rationalised three related government bodies into the one unit. It typically comes up with neo-liberal policy prescriptions with reflect its mainstream economics approach. Its previous findings have spawned deregulation in many industries and sectors and supports privatisation and out-sourcing of public activity at the expense of employment. It has never answered the critique that its concern about the damage of so-called “microeconomic inefficiencies” are out of all proportion to the losses its imposes via unemployment.

Anyway, it seems to have dropped that charter in this report.

The motivation for the Enquiry was the:

Strong growth in executive remuneration from the 1990s to 2007, and instances of large payments despite poor company performance, have fuelled community concerns that executive remuneration is out of control.

They note (see Overview) that “some past trend and specific pay outcomes appear inconsistent with an efficient executive labour market, and possibly weakened company performance” and that “some termination payments look excessive and could indicate compliant boards”.

However they say that “the way forward is not to by-pass the central role of boards. Capping pay or introducing a binding shareholder vote on it would be impractical and costly” and instead say that “the corporate governance framework should be strengthened”.

Initially, the draft report had recommended a “two strikes and you’re out” proposal which would have forced company directors to stand for re-election if executive pay deals were twice rejected by 25 per cent of the shareholders.

The Productivity Commission claimed that “company representatives, as well as advisers to companies and institutional shareholders, considered that the second strike would have significant downside risks” which they listed as:

– conflate the advisory signal on remuneration with the prospect of spilling the board, thereby deterring some investors from expressing dissatisfaction with the remuneration report

– lead boards to take the line of least resistance and adopt generic (‘vanilla’) pay practices likely to be acceptable to proxy advisers and others, rather than seek to devise innovative pay structures that better met the specific needs of the company

– lead to some directors choosing not to recontest their positions if forced to present themselves for re-election over perceived failures on remuneration

matters– provide a ready vehicle for shareholders to pursue objectives or agendas unrelated to remuneration

The main claim was that a minority of shareholders could force a board spill. However, if you believe any of this is more than special pleading then you will believe anything. But the Commission bowed to the pressure and finally settled on a recommended change to the Corporations Act 2001 to read that if there are “more than 50 per cent of eligible votes cast, the board would be required to give notice that such an extraordinary general meeting will be held within 90 days.”

The business lobby, who are never happy unless they are receiving public handouts with no reciprocation required, are still angered with these conditions and claimed this “would turn remuneration into a stalking horse for other issues” (Source)

The Commission also reject any notion of a “binding shareholder vote on executive pay … [as being] … impractical and costly.” They also rejected the trade union request for a salary cap on CEO and non-CEO pay.

So we will not expect to many reforms which will empower shareholders to discipline what the directors of the companies that the shareholders own do with their capital.

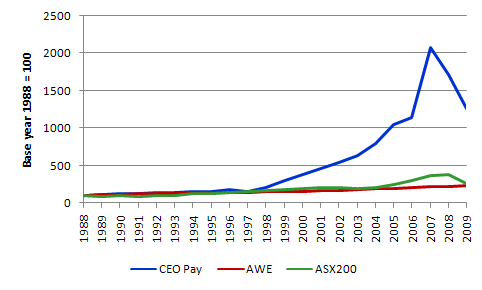

As an aside, I did some analysis to see how executive salaries had tracked relative to growth in share valuations of the major companies and also relative to average weekly earnings. The following graph is indicative as the data issues are fairly difficult. It shows the from the evolution of CEO pay in Australia, Average Weekly (Total) Earnings (AWE) and the S&P/ASX200 share price index from 1988-89 to 2008-09.

The CEO pay data came from Kryger (1999) from 1988 to 1998 and then from the Productivity Commission Appendix B for 2003-04 to 2008-09. I then just filled in the gap via linear interpolation which will not be that inaccurate. The S&P/ASX200 index and Average Weekly (Total) Earnings (AWE) comes from the Reserve Bank database.

I then converted the series into index number form for comparison with base year 1988-89 = 100. The graph is self-explanatory. The rapid growth in CEO pay begins just after the previous conservative government took over and started deregulating the labour market making it harder for workers to access pay rises.

My conclusion: there is a problem. The Productivity Commission report has dodged the issue. Bad luck Australia.

Anyway, all this was an aside – a sort of mental connection – with some other things I have read today. One particular paper I found interesting (in its audacity) was arguing that deficits are “good” because they will discipline government spending more than if a balanced budget was pursued.

In the Hoover Digest (Number 3, 2008), an article When Deficits Make Sense appears written by one Dino Falaschetti, who lists his affiliation as a Hoover fellow in addition to his university post in Florida.

You can see the full working paper at his SSRN archive – Deficits do Matter: They can Improve Government Quality.

The Hoover Institution at Stanford University was set up by former US President Herbert Hoover, who dithered while the US went south in the early years of the Great Depression. The Institution’s mission statement reads that:

… The principles of individual, economic, and political freedom; private enterprise; and representative government were fundamental to the vision of the Institution’s founder. By collecting knowledge, generating ideas, and disseminating both, the Institution seeks to secure and safeguard peace, improve the human condition, and limit government intrusion into the lives of individuals.

So it is a free market biased organisation whose fellows include known conservatives economists like Robert Barro, Gary Becker, John Taylor, Thomas Sargent to name a few.

Falaschetti’s main proposition is that while all sides of politics think the federal “government borrows too much” it doesn’t necessarily follow that the government should try to balance its budget. He says that “balanced budget spending can actually facilitate unproductive tax transfers”.

He claims that:

Indeed, while the invisible hand of markets pushes for win-win bargains, the visible hand of government favors a plurality of voters at the expense of others.

The conclusion is that “running deficits appears to be more solution than problem”. You may be wondering what his line of argument is going to be given this is a conservative institute advocating budget deficits over balanced budgets.

Falaschetti’s second main proposition is that:

Because voting “markets” tend to take from those without a voice, tax-financed spending often channels resources to politically attractive (though not always productive) uses. Financial markets, on the other hand, reward making more than taking. Having to fund deficits can thus replace political manoeuvring with market discipline.

First, it is clear that he doesn’t understand the way the modern monetary system operates in the sense that taxes do not finance government spending. The pork-barrelling in politics however, does involve “tax” and “spending” bribes because national governments choose to mislead the electorate either intentionally or through ignorance about the true nature of their currency monopoly.

Second, his concept of productivity is very narrow – apparently the dictates of the financial markets determine what is best for society. So it is better to “fund” government spending by selling debt because as you will see he thinks this invokes “market discipline” which is a superior form of discipline according to this argument than that which is exercised via the ballot box.

We might ask why bother with elections? Why not just let Wall Street and its regional derivatives (pun not intended) nominate the government of the day in each nation and give us all “win-win” public spending outcomes? I know – you will say that effectively that is what happens anyway. Probably true.

But Falaschetti thinks that financial markets know best how to use resources:

… financial markets, despite recent credit channel difficulties, discipline public spending better than voting markets do. A “bridge to nowhere,” such as the multimillion-dollar span recently proposed in Alaska, would have a hard time attracting financial capital on a cost-benefit basis. But voting markets can forge ahead anyway, spreading the tax costs of unproductive projects widely while concentrating the benefits onto politically attractive constituencies. By more transparently distinguishing between political redistributions and sound public investment, running deficits can improve government quality.

So you get the drift. “Bridges to nowhere” would not be funded if financial markets were the arbiters. This is the usual argument made about public allocations – that the pattern of spending would not resemble that made by profit maximising capitalists who have to answer to their shareholders.

By the way, the accountability to shareholders is why I tied the Productivity Commission report and this article together.

He talks about “credit channel difficulties” as they were just a hiccup – an aside that hasn’t altered anything much. He seems to forget that the current global economic crisis began as a financial crisis driven by irrational greed and dishonest behaviour within the financial markets. The record of these markets in determining what is a “productive” investment is now highly questionable.

Is Falaschetti really telling us that the $billions that are tied up in collateralised debt obligations and the $US30 trillion outstanding credit default swaps are exemplars of “productive” allocations of capital?

How many people have lost their life savings as a result of the financial markets folly?

How many people in less developed countries have starved from the increased poverty that the financial crisis has imposed on their countries?

In this context, I was reminded of the speech Adair Turner, Chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority gave to a dinner at The Mansion House, London on September 22, 2009. He said:

This was the worst crisis for 70 years … a new Great Depression – was only averted by quite exceptional policy measures. Despite these measures major economic harm has occurred. Hundreds of thousands of British people are newly unemployed; tens of thousands have lost houses to repossession; and British citizens will be burdened for many years … because of an economic crisis whose origins lay in the financial system, a crisis cooked up in trading rooms where not just a few but many people earned annual bonuses equal to a lifetime’s earnings of some of those now suffering the consequences. We cannot go back to business as usual and accept the risk that a similar crisis occurs again in ten or 20 years’ time … while the financial services industry performs many economically vital functions, and will continue to play a large and important role in London’s economy, some financial activities which proliferated over the last ten years were ‘socially useless’, and some parts of the system were swollen beyond their optimal size.

He also quoted the Chairman of the British Bankers’ Association who said:

… in recent years, banks have chased short-term profits by introducing complex products of no real use to humanity.

Financial markets are, in the most part, unproductive and produce very little of any value to the broader community. That is at the best of times. But the recent crisis has demonstrated that when they over-extend they have lethal consequences for the real economy.

People and nations now suffering unemployment, poverty, and, in some cases, starvation, had nothing to do with the development of all the shady products that the geniuses on Wall Street invented and pushed often fraudulently, onto ignorant investors.

Further, if private cost-benefit is to be the arbiter of where activity is best focused then a significant number of projects that obviously generate social wealth would never be funded. Society would be much worse off as a consequence. I can think of countless examples where the private markets would never have provided a socially-beneficial activity or resource.

In other words, there is a serious flaw in the proposition that financial markets are the best judges of social costs and benefits. Even mainstream microeconomics textbook have sections (if you can find them) on the divergence between social and private calculations and the need for non-market interventions to resolve the differences.

Falaschetti doesn’t consider government redistributive efforts to be beneficial to the economy. He says that economies prosper “when governance institutions reward productive efforts, and suffer when individuals instead seek redistributive rents”. So the implication is that public education and public health that promotes quality human capital formation in poor areas when it otherwise would not occur are not productive?

He also claims that redistributive policies (where governments provide benefits from its spending to specific groups to garner political support) are bad enough but then “politically attractive tax-and-transfer projects tend to shrink economic opportunities” because they “encourage individuals to lobby to be members of favored groups”.

So financial markets apparently do not lobby for specially-pleaded advantages? I wonder how he explains the bailouts that have occurred with the limited oversight by the US and other governments and the clear evidence that public money has been used by the players in the financial markets to reward those whose criminality and imprudence caused the whole crisis in the first place.

Falaschetti claims that to “maximize the benefits of public spending” there has to be a “funding mechanism that discourages inefficient” spending. In this context he says that :

Voters in corporations “that is, shareholders” readily agree to run deficits, in part because debt capital offers important advantages in governing a firm’s management. Likewise, government bondholders put their money where their mouths are and thus help rein in unproductive tax redistributions. Financial markets can give us a better idea of the appropriate scope of government activity and encourage a less wasteful employment of public resources once that scope is set.

He thinks the within-generational transfers implied by tax favourtism is more of a problem than the debt transferring resources from future generations to the present” because “debt also embodies a number of self-policing mechanisms, whereas taxes create relatively little discipline on how governments spend resources”.

The first of the alleged self-policing mechanisms are:

By selling off bonds when creditworthiness deteriorates, financial markets continually monitor the potential for public spending to decrease the government’s repayment ability.

I laughed at this point. While there is no risk of solvency of a national government defaulting on obligations denominated in its own currency in a modern monetary economy with flexible exchange rates the point being made here is different to his primary justification.

Notwithstanding the obvious reality that sovereign governments have no solvency risk, the financial markets do waste their time talking about sovereign default risks and the credit rating agencies make money by conditioning (fuelling) this conversation. It is a glaring example of bright minds filling up their days with unproductive activity.

If you do some research and talk to people in financial markets you will come to the conclusion that the concept of creditworthiness of sovereign debt is quite different from a neo-classical assessment of whether a particular dollar of public spending is productive.

You might like to read this Fitch sovereign rating methodology particularly the “Checklist of Sovereign Rating Criteria”.

If you examine that list you will see that an assessment of “creditworthiness” however misguided that is in the case of a sovereign government that issues its own currency is rather removed from the process that Falaschetti envisages.

It is true that bond prices will fall and yields rise if the “financial markets” are spooked by the credit ratings. But this is in no way a reflection of a cost-benefit analysis performed by the bond traders on whether the dollars being spent are “productive” or not. The bond investors are just wanting a safe return.

Finally, Falaschetti concludes that:

Economists have long debated whether deficits boost consumption during economic downturns or instead make their way into savings. Deficits do matter, but perhaps less for fiscal stimulus and more for disciplining public spending. To attract funding through debt markets, spending proposals must reasonably promise to strengthen society’s repayment ability. Moreover, debt markets continually evaluate the price at which government obligations are traded and thus transparently report on the credibility of such promises. Running deficits, not balancing budgets, can productively constrain governments by raising the price on unproductive spending while readily supporting public projects that strengthen economic performance.

So he really wants less spending and taxes overall. But his conception that bond markets are continually judging projects on their capacity to “strengthen society’s repayment ability” is far-fetched.

It is difficult to conceive of how we would ever measure “society’s repayment ability” anyway? Further, even if we guess at what he means, one wonders what the “repayment ability” might be of the billions of USD that have been spent in Afghanistan killing and maiming?

Perhaps, the bond markets who line up without fail to buy US government debt have worked out that the US government is part of the heroin trade centred around that part of the world?

Further, rising bond yields typically will rise when there is a diversification of investment opportunities available in a growing economy. So bonds become relatively less attractive because private assets offer higher returns and the higher risk is discounted in the growth environment.

There is no coherence in the statement that variations in bond yields provide an index of the public spending capacity to increase society’s repayment ability, whatever that term actually means.

That is enough for today.

British Bankers’ Association here. Interesting article. We offer a quick clarification if we may.

Lord Turner did use a quote from our chairman, Stephen Green, to support his view that some of the City’s trading activity was “socially useless”. But Turner failed to set out the context of Stephen’s comments:

“At our best, what we do allows businesses to supply products and services that customers need; allows individuals to own homes and cars; to save for a rainy day and for retirement; and to protect themselves and their businesses against the unpredictable. If we care about human freedom and human well-being, we cannot do without these functions.

“But at their worst, financial markets can be engines of destructive excess. In recent years, banks have chased short term profits by introducing complex products of no real use to humanity. It is clear that very many innovations introduced by the financial markets have been socially useful, and indeed are critical to economic and social development to our prosperity, in short.

“But it is equally clear that some parts of our industry had become overblown, and that certain products and services failed the tests of usefulness, suitability and transparency.

“If we are to regain the position of trust and confidence that is a fundamentally important mark of social and economic health, the financial industry will need to learn the lessons of a crisis that has shocked and frightened the world.”

Hi bill,

Couldn’t agree more with this:

“But his conception that bond markets are continually judging projects on their capacity to “strengthen society’s repayment ability” is far-fetched.”

On this matter, I have a related question. Assuming a government followed your prescriptions and simply spent without issuing bonds, and balanced that with liquidity removal via taxation and possibly via paying interest on reserves, then we can say this government has no need to issue long bonds.

Because the government does not need to issue long bonds, does it not follow that they can then control the entire yield curve by simply issuing sufficient bonds of of mid and long maturity such that the combination of supply and demand of these securities achieves a given target 25 year rate?

The only positive I take from the extraordinary pay levels of executives is that there must be a tight supply of unethical actors in the executive labor market.

Also, how commentators can get away with statements about government-funded “bridges to nowhere” while ignoring much larger privately-funded debacles like Dubai World and think that they have any credibility is beyond me.

It is interesting that different tactics are being used to “argue” against increased government spend – the pressure on the US to avoid a 2nd stimulus is going to be the sideshow of Q1 2010.

We need a prediction contest – my bet is that there the US Congress will pass a 2nd stimulus of relatively small amount and deferred release schedule.

Scepticus,

Good point about the yield curve. The government can “set the yield curve”. One may raise objection and dismiss the claim because data shows that the overnight rates fluctuate around the overnight rate target but that is because of lack of proper understanding and use of insufficient tools. The CB can just announce the price of each Treasury security and be willing to buy/sell it at that price. With the CB paying interest (=target) on reserves, – the excess reserves if any – will earn the overnight rate. The CB should also set the discount window – the rate at which it lends to banks – at the target rate. This way, the whole yield curve can be made “exogenous”.

Of course this does not serve any public purpose, so might as well stop issuing Treasuries or have maximum maturity ~ 3 months.

ramanan, without any guidance from the CB as to the long term risk free rate, how do you imagine the private sector would price a 25 year mortgage?

Dear Scepticus

Poor dears … they would have to develop their own low risk asset to replace the public (corporate welfare) bond!

best wishes

bill

Bill, ins’t that exactly what they were trying to do with the shadown banking sector.

You know, create informationally insensitive debt (akin to a deposit account) by taking lodsa mortgages and packaging them up in an opaque fixed income asset which is more or less interchangable with another opaque fixedincome asset (while the music is playing)? And then they use that as collateral for repos in the shadow banking sector. That is, I post MBS collateral with X nominal value and you give me access to 0.95X wholesale funding which I then use to source more loans and make more MBS?

That way the wholesaler gets a place to deposit very large sums of money with the repo collateral acting as deposit insurance.

is it wise to leave all this to the private sector without any kind of benchmark for the more risk averse to cleave to?

Dear scepticus

Yes, securitised mortgages were a possible contender for a low-risk privately created asset. The problem was that they were corrupted by the con-artists and used to create other derivative assets which were useless.

If you also regulate most of the financial sector out of business and require banks have to hold all their own loans they will soon work out what a 25-year mortgage is worth – the level of demand will tell them.

best wishes

bill

Hi Scepticus

This is essentially already done in swap markets, and there were a number of articles suggesting these could/would rather seemlessly become the new benchmarks back in 2000 when everyone erroneously thought the US would run surpluses large enough over the next 10 years to pay off the national debt. As an aside, Randy, Bill, Warren, and others in our “camp” were writing at the same time that it would never happen given the implications for the private sector financial balance.

Best,

Scott

Hi scott, do you have links to some of those writings you’re talknig about? Would love to read them.

Thx.

The one I can recall off the top of my head is here: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/2000n1.html . See the papers/comments related to session 4.

Best,

Scott

You said:

It is true that bond prices will fall and yields rise if the “financial markets” are spooked by the credit ratings. But this is in no way a reflection of a cost-benefit analysis performed by the bond traders on whether the dollars being spent are “productive” or not. The bond investors are just wanting a safe return.

Other than cases of war financing where the immediate survival of the regime is in question, you are correct that bond investors generally DON’T care what the money is spent on. However, if the spending is rising fast enough that the prospective financing capabilities of the sovereign come into question, OR the prospect of monetization by the central bank arises, bond investors will revolt. This process is less an analysis of the productivity of current spending than an analysis of the capacity for future spending. BOTH the productivity of current spending and the willingness of government to accelerate future spending on projects the bond market deems unproductive figure in the calculation however. In this way the bond market is more coal mine canary than ongoing arbiter of efficiency.

ummmm, regarding the financialization of the economy and the need “to strengthen society’s repayment ability” , have you read Steven Lachance’s “How Debt Money Goes Broke”?

And would you care to comment on this fractured debtor-creditor relationship.

Please.