I have been a consistent critic of the way in which the British Labour Party,…

Real wage cuts do not stimulate employment

In last week’s blog – Massive real wage cuts will not improve growth prospects – I considered the mounting evidence that austerity is leading to massive cuts in real wages for workers in Britain without commensurate gains in employment being evident. I have been doing some detailed work on the movements in employment and real wages in Britain over the last decade or so and today some of the more accessible work is presented. You will soon see that the mainstream view that cutting real wages is good for the economy is as absurd as the argument that a fiscal contraction expansion is the path to prosperity. Both policy options are the path to entrenched unemployment and increased poverty rates – exactly the outcome that has befallen the British population as a result of their moronic government policy stance.

The blog mentioned in the introduction examined the recent report from the British Institute for Fiscal Studies – What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle?. The Report painted sorry picture for workers over the course of this recession, which is characterised as the “longest and deepest slump in a century”.

The Report studied the evolution of real wages between 2007 and 2012 and found that “aggregate change was -5.3%”.

The UK Guardian article (June 12, 2013) – Workers suffer deepest cut in real wages since records began, IFS shows – also considered the Report and wrote that:

The report finds that since the start of the recession real wages have fallen by more than in any comparable five-year period. It also highlights an “unprecedented” drop in productivity as output has tumbled faster than employment.

The IFS Report also noted that:

The last time that such a high proportion of workers faced real wage cuts was between 1976 and 1977, when inflation exceeded 15%, while the proportions of nominal wage freezes and cuts are the highest since the series began in the mid 1970s … there is also strong evidence of substantial nominal and real wage reductions occurring within jobs.

Which means that the current period is undermining nominal wages received rather than inflation deflating the real value of those nominal wages (that is, nominal wages growth failing to keep pace with inflation). It is very rare that money wages are cut.

The IFS Report also investigated whether the real wage cut was due to “compositional factors” – that is, “on the basis of changes to the characteristics of individuals in the workforce and the jobs that they do”.

They found that when compositional changes are controlled for they “would have expected wages to increase by 3.3%, all other things being equal”.

Which means that:

… none of the aggregate wage fall can be explained by changes to the composition of the workforce on the basis of characteristics that we observe and hence must instead all be due to changes to the parameter values associated with (or returns to) particular characteristics instead.

The Report investigates why workers are “so much more likely to have experienced nominal wage freezes or cuts during this recession compared to previous recession”.

They find that there has been a “dramatic decline in trade union membership over the last 30 years … accompanied by a reduction in the proportion of employees covered by collective bargaining, which appears to have made it easier for employers to hold constant or reduce insiders’ wages”.

This is a world-wide trend and one of the defining characteristics of the neo-liberal period – that relentless attack on the capacity of the workers to translate productivity growth into real wages growth.

A reasonable hypothesis at present is that the austerity attacks on public services and pay and conditions has nothing at all to do with establishing “fiscal sustainability”. The British government along with most governments has created a massive smokescreen by dragging in the mainstream macroeconomics myths about public deficits and public debt to justify their withering attacks.

The question has always been whether the fiscal austerity is the act of religious zealots who genuinely believe the postulates of the mainstream macroeconomists despite the evidence base that is overwhelmingly unsupportive of those postulates or whether there is something else going on.

Clearly, the religious commitment to the austerity is undoubted. The minds of these politicians and more particularly their advisors (both political and bureaucratic) are obviously addled by the flawed logic served up to them by the mainstream of my profession. There is a high proportion of true believers among this cohort.

I deal with them often in the course of a week and have a fairly good understanding of what they think and know about economics.

However, at a deeper level, there are others who seek to influence this cohort who don’t operate at the level of economic theory. They are purely interested in furthering their class interests and see austerity as a way of inflicting massive damage on the capacity of the working class to enjoy a fair share of the economic growth.

This elite group are also willing to sacrifice the interests of their peers in small business and other sectors who are also damaged by austerity.

So, in a way, trying to make progress via a debate about the validity of economic theory is only a partial strategy when seeking a change to this erosion of worker welfare.

Showing the economic flaws in the arguments used to justify austerity hopefully helps a bit to turn the political tide away from neo-liberal policy options.

There is evidence that some progress is being made. The IMF, for example, is severely compromised now and the mixed messages it is pumping out regularly is evidence of that. They have been so discredited by the their own failures and the millions of jobs that have been lost as a result that they now are almost advocating an anti-austerity message.

What we learned in the pPost Second World War period up to the mid-1970s was that although the elites hated full employment and worked to undermine the politics that supported it, the collective will of the voters in favour of strong employment and a highly supportive Welfare State was compelling.

Political parties, even the conservative side of politics, were forced by the sway of votes to act as mediators in the class struggle between wages and capital rather than take sides, as they are doing now (in favour of capital).

That is why I think political pressure rising from the weight of evidence is still relevant and that is why I write the blog. But I am not naive enough to assume that this nasty echelon of elites will go any time soon.

Anyway, what about evidence? I was curious about the IFS Report and wanted to find out at the sub-aggregate (industry) level what has been happened to real hourly earnings and employment since the start of the crisis and, in particular, since the election of the current British government.

By way of background, please read my blog – Keynes and the Classics – Part 4 – for an introduction to the British Treasury view of the 1930s, which has resurfaced in the current crisis.

The Classical view of the 1930s expressed by the British Treasury (which became known as the Treasury View) centred on whether a person could become involuntary unemployed.

The “Treasury View” denied the existence of involuntary unemployment and argued that fiscal policy (government spending) could not enhance national prosperity by creating employment.

In his 1929 budget speech – (delivered Monday, April 25, 1929 – see Hansard. (1929) HC Deb 15 April 1929, vol. 227, cc53-6 for details), the then British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill outlined the “Treasury View” and denied that fiscal policy would deliver lasting employment gains:

… the orthodox Treasury doctrine … has steadfastly held that, whatever might be the political or social advantages, very little additional employment and no permanent additional employment can in fact and as a general rule be created by State borrowing and State expenditure.

The Treasury View considered that unemployment (beyond the frictional level) was caused by real wages being above the equilibrium level, principally because money wages were downwardly rigid.

Accordingly, the cure for unemployment was simple – allow money wages to fall in the face of the excess supply of labour – so that the real wage could adjust to the “full employment” productivity level. The only role for government in this process was to ensure that wage flexibility was possible.

John Maynard Keynes disputed this reasoning and outlined a new approach to the labour market, which provided an explanation for mass unemployment that was independent of whether wages were flexible or not. In other words, he set out to show that the existence of mass unemployment was not related to the question of wage flexibility.

But the Treasury View is still taught to students as the mainstream explanation for unemployment – under the guise of marginal productivity theory.

The current period in the UK is very interesting – if I put on the dispassionate researcher hat (which is hard to do – remain dispassionate that is) – because it is providing an excellent laboratory for assessing the validity of a number of key mainstream propositions.

We already have enough data in to reject the fiscal contraction expansion” claims offered up by the David Cameron and all (including the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF).

Upon election, the current British government claimed that budget deficits are not required to achieve growth. They rejected the view that government deficits could stimulate production by increasing overall spending when households and firms were reluctant to spend. This is classic Treasury View.

In his 1929 budget speech – Churchill said:

The orthodox Treasury view, and after all British finance has long been regarded as a model to many countries, is that when the Government borrow in the money market it becomes a new competitor with industry and engrosses to itself resources which would otherwise have been employed by private enterprise, and in the process it raises the rent of money to all who have need of it.

In modern terms, students are told that public spending crowds out private spending – this is straight from the Treasury View of the 1930s dressed up a bit in modern language.

David Cameron and George Osborne told the British people that the economy could achieve an “expansionary fiscal contraction” – despite all logic and evidence pointing to the absurdity of this notion.

They held fast that by cutting public spending, more private spending will occur. To justify that inanity, they appealed to the notion that is deeply ingrained in mainstream macroeconomics but rarely fully understood – “Ricardian Equivalence”. The name is fancy but the idea is, in fact, simple – like most of mainstream economics. The substance is thin but the jargon is complex – which hides the lack of substance.< The idea is this: Consumers and firms are allegedly so terrified of higher future tax burdens (needed, the argument goes, to pay off those massive deficits) that they increase saving now to ensure they can meet their future tax obligations. So increased government spending is met by reductions in private spending-stalemate. But, as the neoliberals argue, if governments announce austerity measures, private spending will increase because of the collective relief that future tax obligations will be lower and economic growth will return. Please read my blog - How are the laboratory rats going? – for a detailed critique of this assertion.

We also know that the 5 odd years of relatively high deficits and massive central bank reserve operations have not led to escalating interest rates, hyperinflation (or even accelerating inflation), or mass uprisings of those amorphous (but apparently dangerous and ever-present) bond vigilantes.

None of those myths have held water.

As the data series expand in length we are getting more information that will allow us to more formally (using econometric and other statistical techniques) test some of the key propositions that mainstream economists use to justify the austerity push, which the sneaky elites see as a way of finishing off the agenda so rudely interrupted by the crisis.

Anyway, I have been examining the recent trends in industry employment and real hourly earnings in Britain and here are some of the things I have found to date.

As a warning, the analysis that follows is not a formal attack on Classical employment theory. Graphical analysis helps us frame ideas and get a feel for what more sophisticated statistical analysis reveals. But it only takes us so far. So be cautious in the way you read the next section.

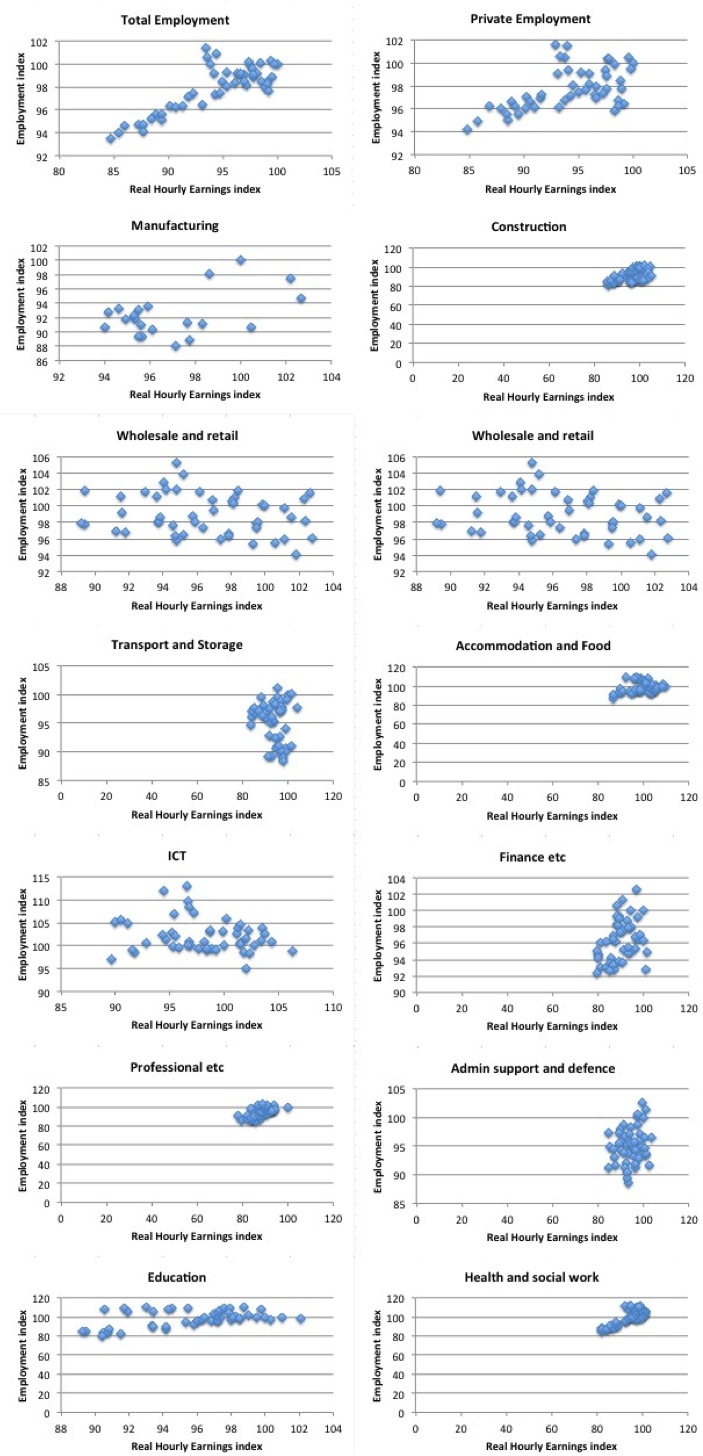

The bottom line though is that with massive real wage cuts in most industry sectors in the UK over the last 5 years one would expect there to be strong positive employment outcomes if the orthodox marginal productivity theory was correct. I realise that productivity has been moving around and so simple cross plots of real wages and employment growth may just be dotting so-called “equilibrium” points (demand equals supply) for a whole map of shifting supply and demand curves (the so-called identification problem).

But my experienced eye tells me that notwithstanding that possibility, the productivity shifts that have been going on do not stop me from concluding that the Classical relationship between real wage movements and employment at the industry level are not present in the data available from the British Office of National Statistics.

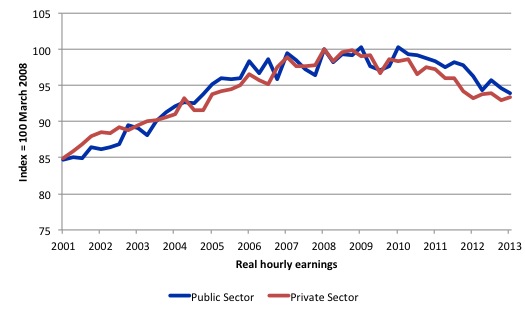

The first graph shows real hourly earnings (sourced from – ONS and deflated with the All Groups CPI) for the public and private sectors in Britain from March-quarter 2001 to the March-quarter 2013.

The data is indexed at 100 at the March-quarter 2008 (the turning point in the cycle). The real wage cuts have been harsh in both sectors.

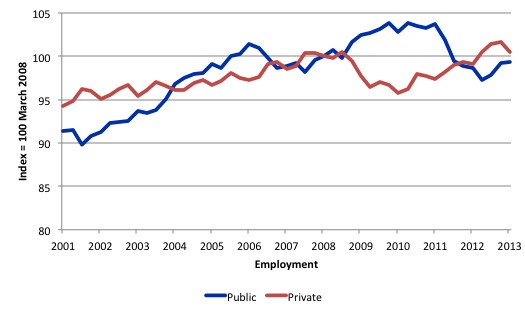

The next graph shows the evolution of employment in the public and private sectors in Britain from March-quarter 2001 to the March-quarter 2013. Prior to the crisis there was steady employment growth in both sectors (as real hourly earnings also rose).

The current state is that there have been no effective employment gains since the onset of the crisis – the public index is at 99.3 and the private index is at 100.5 – despite the massive real wage cuts.

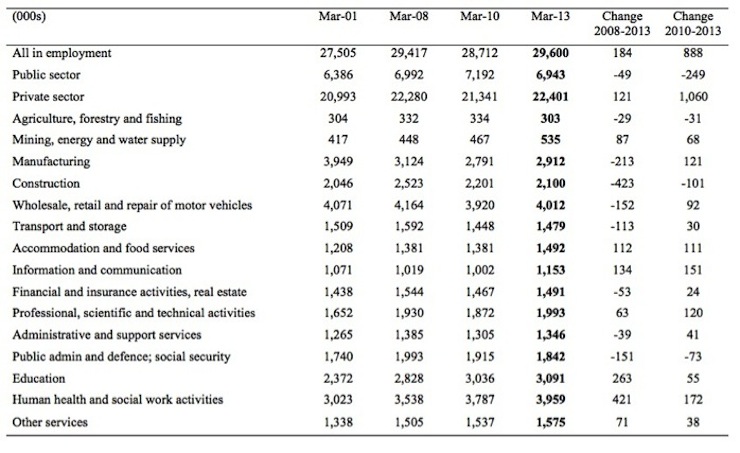

The following Table summarises the employment situation (in thousands) since March 2001 in Britain by sector (total, public, private) and industry (SIC one-digit level).

You can see which sectors have gone backwards since 2008 and which have managed to make some gains. I have also computed the change in employment between 2008-2013 and 2010-2013.

Don’t forget yesterday’s blog – Full employment is still low unemployment and zero underemployment – where I produced a graph showing the plunge in the the employment-population ratio in Britain since the 1970s.

In 2008, the employment-population ratio in the UK was 59.9 per cent. In 2013, it is now below 58.3 per cent. Considering the growth in the Working Age population over that time (1.5 million persons) the drop in the ratio amounts to more than 800 thousand jobs having been lost compared to what would have been the case when the current government took office.

So when the UK government says that 888 thousand jobs have been created since 2010, it is not something that they should celebrate. That is less than 60 per cent of the net new jobs that would have been necessary to keep up with underlying population growth. Of-course, a larger population will typically be associated with more jobs.

But one has to scale the employment growth to the underlying population growth to gain a good idea of what is going on.

The other point to note is that productivity growth has been abysmal in the UK which has attenuated the employment losses that would have occurred given the real output losses. While that is good in the short-run for workers it also damages their future prospects because it undermines the capacity of the economy growth in real living standards overall (irrespective of how the growth is distributed).

So UK workers have two big problems – rising inequality (meaning the distribution is biased against them) and falling future real living standards (due to the sluggish productivity growth). Neither is an attractive mix when combined with the disastrous unemployment and underemployment.

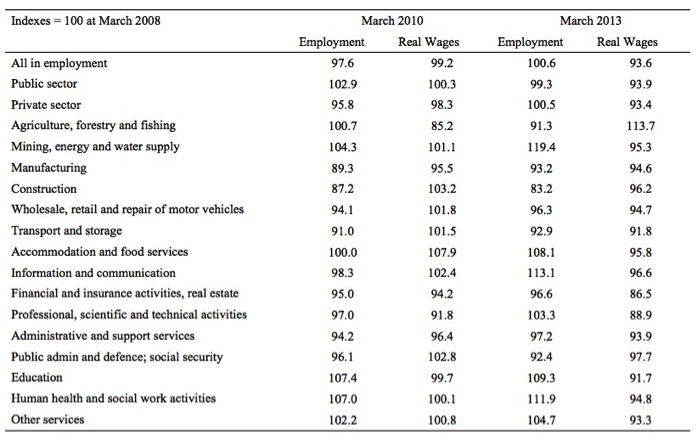

The next Table shows the indexes for employment and real hourly earnings for the March-quarter 2010 and 2013 (noting that the base-quarter is March 2008=100).

Real wages have plummetted in several industries along with employment but the pattern is complex (and certainly productivity movements that I haven’t shown are part of the story).

The following (very long) graph is provided to give you an idea of the relationship between real hourly earnings (horizontal axis) and employment (vertical axis) from March-quarter 2001 to March-quarter 2013 (indexed to 100 in March-quarter 2008) for most of the sectors and industries in the UK.

The manufacturing graph is only from March-2008 to eliminate the strong downward sectoral trend.

The point is that the relationship between the two variables at the sectoral level is anything but classical. More sophisticated analysis is coming another day.

Conclusion

Now that you have made it past that very long graph you will probably appreciate that claims that cutting real wages will improve employment prospects are ill-founded.

That could only happen if somehow the lower real wages reduced the non-government desire to save and stimulated aggregate demand. That is not a likely occurrence.

To learn more about that statement please read the blog – What causes mass unemployment?.

Anyway, chipping away at it still ….

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

Although the report you cited shows that real wage falls are not related to changes in sectorial composition, something that wasn’t addressed was whether changes in productivity *were* influenced by this (given the complex changes in sectorial wages and employment that were observed).

Is this something you will be discussing in a future blog post?

As an aside, Figure 21 of the report is interesting. Despite Paul Krugman’s repeated assertions, nominal wage cuts are not only common (in the UK), they are *more* common than nominal wage freezes in every year from 1975 to the present. And Figure 23 shows that this is not simply a ‘sticky at almost zero’ phenomenon.

Bill, Greg Jericho’s blog in the Guardian seems relevant here “Australia’s flexibility keeps it Strong”. Regarding workers flexibility to move to part time work during the GFC but doesn’t mention the fall in real wages, productivity etc. nor the affect on living standards. Merely touts “flexibility” as a “good thing”.

Dear Bill

A reduction in real wages can stimulate employment in the export sector of a country within a monetary union. Real wage cuts lower labor unit costs and thereby make a country’s goods more competitive. If the country has a very open economy, the employment gains in the export sector may exceed the employment losses in the non-tradable sector due to falling demand caused by the real wage cuts. Germany is a case in point. It has created a lot of jobs in the export sector because it doesn’t allow its wages to rise in tandem with its productivity growth.. I’m of course perfectly aware that such a policy consists of importing demand from other countries in the currency area and is a form exporting unemployment.

Regards. James

” However, at a deeper level, there are others who seek to influence this cohort who don’t operate at the level of economic theory. They are purely interested in furthering their class interests and see austerity as a way of inflicting massive damage on the capacity of the working class to enjoy a fair share of the economic growth. This elite group are also willing to sacrifice the interests of their peers in small business and other sectors who are also damaged by austerity. ”

This is spot on Bill. But just try stating this in the mainstream media and you’ll be labelled a conspiracy kook. And yet there is the smoking gun. No government or collection of governments can possibly be this stupid (to economically destroy their countries with the evidence in front of their noses).

Here is another smoking gun – one that you’ve alluded to in the past – why a change of government seems to make no difference to the economic/political agenda. So-called left governments have taken up the mantra of the right. We in effect have a one-party state, ruled in the background by a plutocracy.

Here is a hypothesis for the European scenario. That the economies of Europe, starting with the poorer south, are being deliberately destroyed in order to speed up the process of federalism in Europe – with the aim to create a United States of Europe(U.S.E). One hint that this is the plan, is the growing calls for fiscal union in Europe – starting by putting the budgets of countries such as Greece, Portugal, Italy, etc under the control of a central authority (Brussels?Berlin?). This is being offered as the alternative to these nations leaving the Euro (which to you, me and your readers would be the obvious way to go). “Oh no!! We can’t allow these nations to fly the coop, now can we?”

And no mention of course, of the ECB using its currency muscle to help these countries along either. No the answer is fiscal union. Fiscal union is probably the last step towards the U.S.E.. After that the nations of Europe become more like the States of the U.S. or the Commonwealth of Australia. The end of sovereignty for Greece, Italy, Portugal, France, etc. So in essence, what I’m suggesting is that behind the economic vandalism of austerity very likely lies a political ambition for the super-elite as well.

I thought the hard core mainstream economic view was that all savings became “intermediated” by the financial system into real investment. If that were so (which off course it isn’t); then Ricardian Equivalence wouldn’t fit even to their imaginary world. Extra saving by savvy foresighted economic agents envisioning future taxes would (by their logic) lead to extra investment as the financial system intermediated those savings into new factories, research and development, workforce training etc. So, thanks to the (bogus) “fact” that financial saving drives investment, increased government spending would result in an economic boost irrespective of how extreme Ricardian Equivalence was.

They can’t have it both ways.