Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – February 9, 2013 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

National accounting shows us that a government surplus equals a non-government deficit. So if the imposition of fiscal austerity ends up generating a budget surpluses then the national income movements will force households and firms overall to be running deficits.

The answer is False.

The point is that the non-government sector is not equivalent to the private domestic sector in the sectoral balance framework. We have to include the impact of the external sector.

So this is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero.

You can also write this as:

(S – I) + (T – G) = (X – M)

Which gives an easier interpretation (especially in relation to this question).

The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (S – I) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

- The Budget balance (T – G) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

Using this version of the sectoral balance framework:

(S – I) + (T – G) = (X – M)

So the domestic balance (left-hand side) – which is the sum of the private domestic sector and the government sector equals the external balance.

For the left-hand side of the equation to be positive (that is, in surplus overall) and the individual sectoral components to be in surplus overall, the right-hand side has to be positive (that is, an external surplus) and of sufficient magnitude.

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

The following graph and accompanying table shows a 8-period sequence where for the first four years the nation is running an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) and for the last four year the external sector is in surplus (2 per cent of GDP).

For the question to be true we should never see the government surplus (T – G > 0) and the private domestic surplus (S – I > 0) simultaneously occurring – which in the terms of the graph will be the green and navy bars being above the zero line together.

You see that in the first four periods that never occurs which tells you that when there is an external deficit (X – M < 0) the private domestic and government sectors cannot simultaneously run surpluses, no matter how hard they might try. The income adjustments will always force one or both of the sectors into deficit.

The sum of the private domestic surplus and government surplus has to equal the external surplus. So that condition defines the situations when the private domestic sector and the government sector can simultaneously pay back debt.

It is only in Period 5 that we see the condition satisfied (see red circle).

That is because the private and government balances (both surpluses) exactly equal the external surplus.

So if the British government was able to pursue an austerity program with a burgeoning external sector then the private domestic sector would be able to save overall and reduce its debt levels. The reality is that this situation is not occurring.

Going back to the sequence, if the private domestic sector tried to push for higher saving overall (say in Period 6), national income would fall (because overall spending fell) and the government surplus would vanish as the automatic stabilisers responded with lower tax revenue and higher welfare payments.

Periods 7 and 8 show what happens when the private domestic sector runs deficits with an external surplus. The combination of the external surplus and the private domestic deficit adding to demand drives the automatic stabilisers to push the government budget into further surplus as economic activity is high. But this growth scenario is unsustainable because it implies an increasing level of indebtedness overall for the private domestic sector which has finite limits. Eventually, that sector will seek to stabilise its balance sheet (which means households and firms will start to save overall). That would reduce domestic income and the budget would move back into deficit (or a smaller surplus) depending on the size of the external surplus.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 2:

A characteristic feature of the neo-liberal period has been the declining share of wages in national income in most nations, which in part, meant that economic growth became more dependent on credit to maintain growth in consumption spending. However it is not necessary for real wages to grow in the coming years to reverse that trend and real wage cuts under austerity programs could result in an increase the wage share.

The answer is True.

A faster rate of real wages growth is not even a necessary condition much less a sufficient condition for a rising wage share.

Abstracting from the share of national income going to government, we can divide national income into the proportion going to workers (the “wage share”) and the proportion going to capital (the “profits share”). For the profit share to fall, the wage share has to rise (given the proportion going to government is relatively constant over time).

The wage share in nominal GDP is expressed as the total wage bill as a percentage of nominal GDP. Economists differentiate between nominal GDP ($GDP), which is total output produced at market prices and real GDP (GDP), which is the actual physical equivalent of the nominal GDP. We will come back to that distinction soon.

To compute the wage share we need to consider total labour costs in production and the flow of production ($GDP) each period.

Employment (L) is a stock and is measured in persons (averaged over some period like a month or a quarter or a year.

The wage bill is a flow and is the product of total employment (L) and the average wage (w) prevailing at any point in time. Stocks (L) become flows if it is multiplied by a flow variable (W). So the wage bill is the total labour costs in production per period.

So the wage bill = W.L

The wage share is just the total labour costs expressed as a proportion of $GDP – (W.L)/$GDP in nominal terms, usually expressed as a percentage. We can actually break this down further.

Labour productivity (LP) is the units of real GDP per person employed per period. Using the symbols already defined this can be written as:

LP = GDP/L

so it tells us what real output (GDP) each labour unit that is added to production produces on average.

We can also define another term that is regularly used in the media – the real wage – which is the purchasing power equivalent on the nominal wage that workers get paid each period. To compute the real wage we need to consider two variables: (a) the nominal wage (W) and the aggregate price level (P).

We might consider the aggregate price level to be measured by the consumer price index (CPI) although there are huge debates about that. But in a sense, this macroeconomic price level doesn’t exist but represents some abstract measure of the general movement in all prices in the economy.

Macroeconomics is hard to learn because it involves these abstract variables that are never observed – like the price level, like “the interest rate” etc. They are just stylisations of the general tendency of all the different prices and interest rates.

Now the nominal wage (W) – that is paid by employers to workers is determined in the labour market – by the contract of employment between the worker and the employer. The price level (P) is determined in the goods market – by the interaction of total supply of output and aggregate demand for that output although there are complex models of firm price setting that use cost-plus mark-up formulas with demand just determining volume sold. We shouldn’t get into those debates here.

The inflation rate is just the continuous growth in the price level (P). A once-off adjustment in the price level is not considered by economists to constitute inflation.

So the real wage (w) tells us what volume of real goods and services the nominal wage (W) will be able to command and is obviously influenced by the level of W and the price level. For a given W, the lower is P the greater the purchasing power of the nominal wage and so the higher is the real wage (w).

We write the real wage (w) as W/P. So if W = 10 and P = 1, then the real wage (w) = 10 meaning that the current wage will buy 10 units of real output. If P rose to 2 then w = 5, meaning the real wage was now cut by one-half.

So the proposition in the question – that nominal wages grow faster than inflation – tells us that the real wage is rising.

Nominal GDP ($GDP) can be written as P.GDP, where the P values the real physical output.

Now if you put of these concepts together you get an interesting framework. To help you follow the logic here are the terms developed and be careful not to confuse $GDP (nominal) with GDP (real):

- Wage share = (W.L)/$GDP

- Nominal GDP: $GDP = P.GDP

- Labour productivity: LP = GDP/L

- Real wage: w = W/P

By substituting the expression for Nominal GDP into the wage share measure we get:

Wage share = (W.L)/P.GDP

In this area of economics, we often look for alternative way to write this expression – it maintains the equivalence (that is, obeys all the rules of algebra) but presents the expression (in this case the wage share) in a different “view”.

So we can write as an equivalent:

Wage share – (W/P).(L/GDP)

Now if you note that (L/GDP) is the inverse (reciprocal) of the labour productivity term (GDP/L). We can use another rule of algebra (reversing the invert and multiply rule) to rewrite this expression again in a more interpretable fashion.

So an equivalent but more convenient measure of the wage share is:

Wage share = (W/P)/(GDP/L) – that is, the real wage (W/P) divided by labour productivity (GDP/L).

I won’t show this but I could also express this in growth terms such that if the growth in the real wage equals labour productivity growth the wage share is constant. The algebra is simple but we have done enough of that already.

That journey might have seemed difficult to non-economists (or those not well-versed in algebra) but it produces a very easy to understand formula for the wage share.

Two other points to note. The wage share is also equivalent to the real unit labour cost (RULC) measures that Treasuries and central banks use to describe trends in costs within the economy. Please read my blog – Saturday Quiz – May 15, 2010 – answers and discussion – for more discussion on this point.

Now it becomes obvious that if the nominal wage (W) grows faster than the price level (P) then the real wage is growing. But that doesn’t automatically lead to a growing wage share. So the blanket proposition stated in the question is false.

If the real wage is growing at the same rate as labour productivity, then both terms in the wage share ratio are equal and so the wage share is constant.

If the real wage is growing but labour productivity is growing faster, then the wage share will fall.

Only if the real wage is growing faster than labour productivity , will the wage share rise.

The wage share was constant for a long time during the Post Second World period and this constancy was so marked that Kaldor (the Cambridge economist) termed it one of the great “stylised” facts. So real wages grew in line with productivity growth which was the source of increasing living standards for workers.

The productivity growth provided the “room” in the distribution system for workers to enjoy a greater command over real production and thus higher living standards without threatening inflation.

Since the mid-1980s, the neo-liberal assault on workers’ rights (trade union attacks; deregulation; privatisation; persistently high unemployment) has seen this nexus between real wages and labour productivity growth broken. So while real wages have been stagnant or growing modestly, this growth has been dwarfed by labour productivity growth.

So the question is True because you have to consider labour productivity growth in addition to real wages growth before you can make conclusions about the movements in factor shares in national income.

It would be highly undesirable though to run a strategy that undermined productivity growth.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

The payment of a positive interest return by the central bank on overnight bank reserves does not eliminate the need for it to conduct open market operations to ensure its policy rate is sustained (ignore any reserve requirements).

The answer is True.

This question tests your knowledge of central bank operations – in particular, its liquidity management operations that are used to maintain its target rate of interest in a modern monetary economy.

Mainstream macroeconomics textbooks tell students that monetary policy describes the processes by which the central bank determines “the total amount of money in existence or to alter that amount”. However, this is not what happens in the real world.

In Mankiw’s Principles of Economics (Chapter 27 First Edition) he say that the central bank has “two related jobs”. The first is to “regulate the banks and ensure the health of the financial system” and the second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

How does the mainstream see the central bank accomplishing this task? Mankiw says:

Fed’s primary tool is open-market operations – the purchase and sale of U.S government bonds … If the FOMC decides to increase the money supply, the Fed creates dollars and uses them buy government bonds from the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the purchase, these dollars are in the hands of the public. Thus an open market purchase of bonds by the Fed increases the money supply. Conversely, if the FOMC decides to decrease the money supply, the Fed sells government bonds from its portfolio to the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the sale, the dollars it receives for the bonds are out of the hands of the public. Thus an open market sale of bonds by the Fed decreases the money supply.

This description of the way the central bank interacts with the banking system and the wider economy is totally false. The reality is that monetary policy is focused on determining the value of a short-term interest rate. Central banks cannot control the money supply. To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply.

As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 (Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector) is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves. Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

With this background in mind, the question is specifically about the dynamics of bank reserves which are used to satisfy any imposed reserve requirements and facilitate the payments system. These dynamics have a direct bearing on monetary policy settings. Given that the dynamics of the reserves can undermine the desired monetary policy stance (as summarised by the policy interest rate setting), the central banks have to engage in liquidity management operations.

What are these liquidity management operations?

Well you first need to appreciate what reserve balances are.

The New York Federal Reserve Bank’s paper – Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy said that:

… reserve balances are used to make interbank payments; thus, they serve as the final form of settlement for a vast array of transactions. The quantity of reserves needed for payment purposes typically far exceeds the quantity consistent with the central bank’s desired interest rate. As a result, central banks must perform a balancing act, drastically increasing the supply of reserves during the day for payment purposes through the provision of daylight reserves (also called daylight credit) and then shrinking the supply back at the end of the day to be consistent with the desired market interest rate.

So the central bank must ensure that all private cheques (that are funded) clear and other interbank transactions occur smoothly as part of its role of maintaining financial stability. But, equally, it must also maintain the bank reserves in aggregate at a level that is consistent with its target policy setting given the relationship between the two.

So operating factors link the level of reserves to the monetary policy setting under certain circumstances. These circumstances require that the return on “excess” reserves held by the banks is below the monetary policy target rate. In addition to setting a lending rate (discount rate), the central bank also sets a support rate which is paid on commercial bank reserves held by the central bank.

Many countries (such as Australia and Canada) maintain a default return on surplus reserve accounts (for example, the Reserve Bank of Australia pays a default return equal to 25 basis points less than the overnight rate on surplus Exchange Settlement accounts). Other countries like the US and Japan have historically offered a zero return on reserves which means persistent excess liquidity would drive the short-term interest rate to zero.

The support rate effectively becomes the interest-rate floor for the economy. If the short-run or operational target interest rate, which represents the current monetary policy stance, is set by the central bank between the discount and support rate. This effectively creates a corridor or a spread within which the short-term interest rates can fluctuate with liquidity variability. It is this spread that the central bank manages in its daily operations.

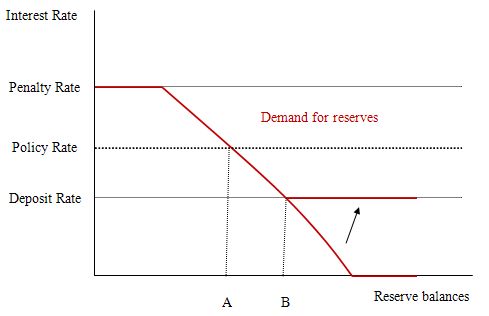

So the issue then becomes – at what level should the support rate be set? To answer that question, I reproduce a version of teh diagram from the FRBNY paper which outlined a simple model of the way in which reserves are manipulated by the central bank as part of its liquidity management operations designed to implement a specific monetary policy target (policy interest rate setting).

I describe the FRBNY model in detail in the blog – Understanding central bank operations so I won’t repeat that explanation.

The penalty rate is the rate the central bank charges for loans to banks to cover shortages of reserves. If the interbank rate is at the penalty rate then the banks will be indifferent as to where they access reserves from so the demand curve is horizontal (shown in red).

Once the price of reserves falls below the penalty rate, banks will then demand reserves according to their requirments (the legal and the perceived). The higher the market rate of interest, the higher is the opportunity cost of holding reserves and hence the lower will be the demand. As rates fall, the opportunity costs fall and the demand for reserves increases. But in all cases, banks will only seek to hold (in aggregate) the levels consistent with their requirements.

At low interest rates (say zero) banks will hold the legally-required reserves plus a buffer that ensures there is no risk of falling short during the operation of the payments system.

Commercial banks choose to hold reserves to ensure they can meet all their obligations with respect to the clearing house (payments) system. Because there is considerable uncertainty (for example, late-day payment flows after the interbank market has closed), a bank may find itself short of reserves. Depending on the circumstances, it may choose to keep a buffer stock of reserves just to meet these contingencies.

So central bank reserves are intrinsic to the payments system where a mass of interbank claims are resolved by manipulating the reserve balances that the banks hold at the central bank. This process has some expectational regularity on a day-to-day basis but stochastic (uncertain) demands for payments also occur which means that banks will hold surplus reserves to avoid paying any penalty arising from having reserve deficiencies at the end of the day (or accounting period).

To understand what is going on not that the diagram is representing the system-wide demand for bank reserves where the horizontal axis measures the total quantity of reserve balances held by banks while the vertical axis measures the market interest rate for overnight loans of these balances

In this diagram there are no required reserves (to simplify matters). We also initially, abstract from the deposit rate for the time being to understand what role it plays if we introduce it.

Without the deposit rate, the central bank has to ensure that it supplies enough reserves to meet demand while still maintaining its policy rate (the monetary policy setting.

So the model can demonstrate that the market rate of interest will be determined by the central bank supply of reserves. So the level of reserves supplied by the central bank supply brings the market rate of interest into line with the policy target rate.

At the supply level shown as Point A, the central bank can hit its monetary policy target rate of interest given the banks’ demand for aggregate reserves. So the central bank announces its target rate then undertakes monetary operations (liquidity management operations) to set the supply of reserves to this target level.

So contrary to what Mankiw’s textbook tells students the reality is that monetary policy is about changing the supply of reserves in such a way that the market rate is equal to the policy rate.

The central bank uses open market operations to manipulate the reserve level and so must be buying and selling government debt to add or drain reserves from the banking system in line with its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system and the central bank didn’t intervene then the market rate would drop towards zero and the central bank would lose control over its target rate (that is, monetary policy would be compromised).

As explained in the blog – Understanding central bank operations – the introduction of a support rate payment (deposit rate) whereby the central bank pays the member banks a return on reserves held overnight changes things considerably.

It clearly can – under certain circumstances – eliminate the need for any open-market operations to manage the volume of bank reserves.

In terms of the diagram, the major impact of the deposit rate is to lift the rate at which the demand curve becomes horizontal (as depicted by the new horizontal red segment moving up via the arrow).

This policy change allows the banks to earn overnight interest on their excess reserve holdings and becomes the minimum market interest rate and defines the lower bound of the corridor within which the market rate can fluctuate without central bank intervention.

So in this diagram, the market interest rate is still set by the supply of reserves (given the demand for reserves) and so the central bank still has to manage reserves appropriately to ensure it can hit its policy target.

If there are excess reserves in the system in this case, and the central bank didn’t intervene, then the market rate will drop to the support rate (at Point B).

So if the central bank wants to maintain control over its target rate it can either set a support rate below the desired policy rate (as in Australia) and then use open market operations to ensure the reserve supply is consistent with Point A or set the support rate equal to the target policy rate.

The answer to the question is thus True because it all depends on where the support rate is set. Only if it set equal to the policy rate will there be no need for the central bank to manage liquidity via open market operations.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Just in the interest of trying it on.

.

Why might it be set at any other level ?