I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

We need more artists and fewer entrepreneurs

When the early neo-liberal governments in Britain, Australia and New Zealand wanted to craft the public debate so that we wouldn’t realise that privatisation was just selling wealth that we already owned collectively to enrich a few of us as well as all the parasitic lawyers and brokers who managed the sales, they pushed the idea that we were all shareholders now. The old idea of capitalists versus workers was dead because we were all basically capitalists and the wealth would grow accordingly. What a disaster that initial experience with the neo-liberal myth has been. Now, that governments are deliberately creating unemployment and undermining paid-work opportunities with fiscal austerity, the public debate is being bombarded with a variation on that same theme. Now we are being told that it is so passe to think in terms of workers and bosses because in reality we are all basically entrepreneurs. Even the most lowly-paid casualised worker who is unfortunate enough to have to eke out an existence via labour hire companies is cast gloriously as a profit-seeking entrepreneur. The rot is seeping into our educational institutions as well.

I recall being on a panel in 2004 or 2005 and the topic was the conservative government’s WorkChoices legislation, which for those abroad was a pernicious piece of law that sought to undermine most of the capacity of unions to bargain and strip essential protections and entitlements from workers. The 2007 election loss they endured was a direct result of them become just a little too ambitious with this legislation.

The problem, of-course, that the current Labor government has left most of the legislative framework in place, despite promising otherwise. The future on the IR front is rather bleak given the next federal election is later this year and the conservatives will certainly win and pick up from where they left off – which means not having to do very much at all as a result of the reluctance of the current government to reject the neo-liberal mindset.

But I digress. There were two of us on that particular panel – yours truly and the other was a young woman who had won some youth of the year award (I cannot recall what exactly was her achievement).

I gave my usual type of presentation. When she started, she immediately tore into me for being old-fashioned and out of touch. She said that none of her generation considered themselves to be “workers” any more. For them, they hot-desked it with their Apple products and walked tall as “entrepreneurs”. She claimed that WorkChoices was fine because workers didn’t want security they wanted freedom to negotiate their own deals and to have time off when they wanted it – “between contracts” – rather than be stuck in an office 48 weeks of the year from 9 to 5. I have never forgotten that term “between contracts”.

It would be easy to ridicule that position but it does reflect the way the narrative that the neo-liberals has spun, has penetrated the daily perceptions of those who are staring at the dysfunction of the system more than most.

This is a generation that faces highly precarious work. A university degree no longer guarantees one secure and well-paid employment. These periods “between contracts” are still what reasonable citizens call unemployment.

This generation is less likely to build up adequate superannuation balances to assist them in a reasonable retirement. They are less likely to be in a position to purchase property – which remains the primary way that the average household generates wealth over their lifetime.

These daring entrepreneurs don’t even know what the reality is.

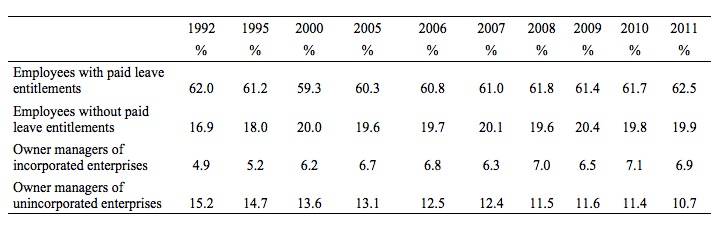

Recent data available from the ABS – Employment type 1992 – 2011 – allows us to see the relative importance of “entrepreneurs” in total employment in Australia. A more thorough analysis would not negate what I am about to say (by way of blog-style evidence).

The following Table is constructed using that data and shows the shares in total employment across different “employment types”. The “Employees with paid leave entitlements” refers to the standard-type employment arrangements that have persisted for years. The second category “Employees without paid leave entitlements” encompasses workers who by bargain or otherwise have lost their holiday entitlements. Most casual workers are in this category now.

Employers often argue that the so-called “casual loadings” on the implied hourly rate make up for the lost paid vacation pay. That claim has been found in arbitration tribunals in Australia to be a lie.

Further, workers in this category tend to lose other benefits that accrue to those in more fixed arrangements. Banks will not lend casual workers money for mortgages. These workers have problems during school vacation times because they have no paid leave. So if they take leave to be with their children they lose income, and, in many cases, they lose their jobs and are replaced by the next person in the queue – given that the total labour underutilisation rate in Australia is currently in excess of 12.5 per cent. So the queue is long.

The entrepreneurial class is not found among the first two categories. You can see that the second category has grown in importance, while the first category has remained stable. So there are plenty of workers left slaving away for a wage.

The idea that there are no “workers” any more is a total myth. In 2011, the official data suggests they made up 82.4 per cent of the total employed labour force. It is true that various pieces of anti-union and anti-worker legislation over this period has undermined the conditions that these workers get. Concepts like the standard working week etc have been eroded and job security has largely disappeared (even for those who still get paid holidays).

But 82.4 per cent is still a fair share and still justifies us thinking about a class of workers, notwithstanding that some of them were conned by the conservatives into buying shares in the public telecommunications company Telstra – only to make major losses as the share value plummeted because the new private management have been largely incompetent. Same goes for our public airline Qantas. Who would bother to fly on that service anymore?

Our so-called entrepreneurs are in the third and fourth categories – and it is clear those in “unincorporated enterprises” – mostly small firms and partnerships – the classic entrepreneurial firms – are in decline as a share in total employment.

Which leads me, in a roundabout way, to this article from the Atlantic (September 24, 2012) – How Liberal Arts Colleges Are Failing America – which I filed away at the time for future comment.

I have a huge database of articles and snippets that one day I will piece together into a coherent whole. They represent parts of a neo-liberal propaganda machine that has changed our world and will leave the next generation poorer than the baby boomers for sure. Once it had achieved that accomplishment, the neo-libs turned on the boomers themselves to strip them of their savings and dignity. So eventually I will put all that together But for now I just sometimes blog about the snippets of joy that I collect like a magpie.

I was reminded of this article by a Bloomberg piece the yesterday (January 9, 2013) – Don’t Call Them Students. They’re Entrepreneurs – which was just rehearsing a variation of the tired old neo-lib theme that the class boundaries that given them the most trouble like workers and capital, owners and workers, students and teachers, etc are just constructs that left-wing ideologues hang on to. The dinosaurs among us. The new age entrepreneurs don’t have time for all that old, worn-out narrative. They are out there – making money – getting the job done – enriching all of us. That sort of theme.

The Bloomberg article reports on the increasing number of American universities that are become swamped with “entrepreneurship programs”:

Entrepreneurship programs have exploded on U.S. campuses, and administrators love to talk about them

There is even a national ranking system of “entrepreneurship units” provided by Princeton Review and Entrepreneur Magazine. Everyone wants to be in on the scene. Remember George W Bush calling the US astronauts “spacial entrepreneurs”! (On January 14, 2004). Which means that French word is probably ” Spationaut(e)” although the same President allegedly did say that “The problem with the French is that they don’t have a word for entrepreneur” (even if that quote is denied).

The universities are seeking to “label” themselves as exciting places where people do stuff after all “(c)olleges that have no entrepreneurship message appear to applicants as old-fashioned and unappreciative”.

The Bloomberg article though finishes on a reflective note:

The only casualty in this forward-looking, product- creating, money-making, social-change enterprise is the old idea of liberal education from Cicero to a few traditionalists in the present: the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. Or, as Cardinal John Henry Newman put it, “liberal knowledge, which stands on its own pretensions, which is independent of sequel, expects no complement, refuses to be informed (as it is called) by any end, or absorbed into any art, in order duly to present itself to our contemplation.”

It cautions US universities of ignoring the humanities and suggests that “(m)aybe an entrepreneur who has read Thucydides or Edith Wharton is more prepared, more savvy and imaginative about new products and solutions than an unlettered competitor”.

Regular readers of my blog will know that I have a bee in my bonnet about the demise of the humanities and the confinement of economics education into business schools.

Here is a sequence of blogs from most recent to most dated that discuss aspects of this theme:

- The humanities is necessary but not sufficient for social transformation – for more discussion on this point.

- Technocrats move over, we need to read some books

- We need more fermenting … much more

- Education – a vehicle for class division

- I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books

The Atlantic article (cited above) was authored by one Scott Gerber who says he “is the founder of the Young Entrepreneur Council” among other things. Apparently he is a “serial entrepreneur”. Apparently, he grew up in a non-entrepreneurial middle class family and knew if he lost his first “$700” venture he could move back with his parents. But that isn’t the point – we know that social background influences life’s choices. It is easy to be an entrepreneur if there is a safety net to fall back on.

The Atlantic article makes a good point that:

A degree does not guarantee you or your children a good job anymore. In fact, it doesn’t guarantee you a job: last year, 1 out of 2 bachelor’s degree holders under 25 were jobless or unemployed. Since the recession, we’ve lost millions of high- and mid-wage jobs — and replaced a handful of those with lower-wage ones. No wonder some young people are giving up entirely — a 16.8 percent unemployment rate plus soaring student loan debt is more than a little discouraging.

The same trend is happening all across the world. In Europe, the plight of the young (even those with university educations) is very grim.

But the conclusions the article draws from this systemic failure to use the skilled labour at its disposable is the problem.

1. “When are Americans going to wake up and realize that the 60s and 70s-era nostalgia for the “value” of a college degree is just that — nostalgia?”

2. “old-guard academic leaders are still clinging to the status quo — and loudly insisting that a four-year liberal arts degree is a worthy investment in every young American’s future.”

The point here is that we should not throw the baby out with the proverbial. It is not the fault of the university courses that the graduates are not gaining employment. That is the slip in logic that the author makes.

The problem is that there are not enough jobs being generated and that is because a macroeconomic spending constraint has been imposed on economies all around the world by governments who have failed to adequately respond to the collapse in non-government spending following the financial crisis.

Trying to solve the problem by people “creating their own jobs” is to descend into the fallacy of composition that bedevils mainstream economic thinking. We are led to believe that if everyone became entrepreneurs and produced a product that there would be jobs for all.

Apart from the fact, that a prior fallacy of composition is that not everyone can become entrepreneurs anyway – someone has to produce the products they dream up – there remains the greater fallacy that spending will match supply irrespective. This is the old Say’s Law myth.

But an appreciation of the way the macroeconomic monetary system actually operates leads one to realise that adequate levels of aggregate demand are never guaranteed by the available supply. Even those the supply (output) has created national income equal to the value of the output, that doesn’t ensure it will all be recycled back into the expenditure stream.

Further, the purpose of education has never been, exclusively, to ensure a person gets a job. There is nothing nostalgic at all about valuing the traditions of literature and culture and the arts. These are the things that separate us, in a not unimportant way, from the beasts that run wild in the jungle. Literature, values, art, music and philosophy set humanity apart.

A deep appreciation of history should lead us to solve problems better and not to repeat mistakes. You will notice that it is a characteristic of the neo-liberal era to revise history to suit itself. The Great Depression was the fault of the government and fiscal policy interventions have made the current crisis worse. That sort of thing.

The Atlantic article says that the question facing educators in America (and presumably everywhere else) is what is:

… the “tangible value” of four years of liberal arts … We keep telling young Americans that a bachelor’s degree in history is as valuable as, say, a chemical engineering degree — but it’s just not true anymore. All degrees are not created equal. And if we — parents, educators, entrepreneurs and nonprofit leaders — maintain this narrow-minded approach, then we are not just failing young indebted Americans and their families. We are harming the long-term vitality of our economy.

Again note the slip in logic. The failings of the labour market are macroeconomic in nature. If economic growth expanded and employment growth quickened then graduates would be first in the queue. So the problem is a lack of employment growth.

There is no evidence that employers are refusing to hire graduates across all the disciplines and holding the jobs “open” until an entrepreneurial graduate appears.

The Atlantic article attempts to cite evidence to substantiate the claim that entrepreneurship programs that are springing up in the US educational system:

… makes … [the students] … more employable. A recent report from Junior Achievement Innovation Initiative and Gallup found that both employers and employees believe America’s workforce must become more entrepreneurial if the U.S. is to remain competitive — 95 and 96 percent, respectively. Only one in 10 believed entrepreneurship was an innate skill.

Which is not the same thing as saying that the firms preferred to employ these students over those who had not undertaken such courses. The Report in question is – The Entrepreneurial Workforce.

In that Report, you will find that:

1. “81 percent of those with responsibilities for hiring believe these new entrants are qualified”.

2. 56 per cent of “those responsible for hiring” did think that “a lack of life skills such as self-motivation, communication and social skills” are a problem for advancement within their companies. But liberal arts course teach all of these things. They are not the monopoly of so-called “entrepreneurship” courses.

3. “(48%) responsible for hiring choose self-motivation first over other factors as being most important to an employee’s success at their company”. Again, a product of a well-designed liberal arts education where the students are encouraged to be resourceful and co-operate. My experience in business-type faculties over many years has taught me that those students are taught to rote-learn, and be competitive rather than learn intrinsic team-building, problem solving skills.

4. Only 43 per cent of those “responsible for hiring” thought it was the responsibility of the education system to prepare “new employees for the workforce”. An equal proportion thought the applicants should prepare themselves, while 6 per cent “believe it’s the responsibility of companies to prepare employees for the workforce”. Again, this is not a beacon call for entrepreneurship programs.

5. “When asked to choose from five possible factors that might limit employees from achieving success at their company, there is no clear consensus among employees or those who are involved in hiring as to the greatest limitation”.

6. In terms of the balance between having the “best technical skills or the ability to work well with others, the ability to work well with others trumps best technical skills as more important for success at the employees’ companies”. Liberal arts courses are intrinsically social and encourage team-building.

7. The “vast majority (96%) of employees feel it is important for the American workforce to become more entrepreneurial in order to keep America competitive in the global market” but around half (46 per cent) thought the “best place to learn entrepreneurship is in grades K-12”. 28 per cent thought it should be learned upon entering the workforce or “cannot be learned, must be born with it”.

While the survey is about exploring entrepreneurship as a virtue which is helpful to a person in their commercial lives it does not substantiate the claims made by the Atlantic author.

Further, life is not confined to one’s participation in commercial activities. One of the features of neo-liberalism is to attempt to commodify everything. Education is broad, whereas the corporate sector is narrow.

I remind readers of the great American author, Harry Braverman who clearly saw (in the early 1970s) the way that neo-liberal would impose its constructs on us and seek to apply them to all aspects of human activity.

In his – Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York, Monthly Review Press, 1974) – Braverman wrote (pages 170-71):

Thus, after a million years of labour, during which humans created not only a complex social culture but in a very real sense created themselves as well, the very cultural-biological trait upon which this entire evolution is founded has been brought, within the last two hundred years, to a crisis, a crisis which Marcuse aptly calls the threat of a “catastrophe of the human essence”. The unity of thought and action, conception and execution, hand and mind which capitalism threatened from its beginnings, is now attacked by a systematic dissolution employing all the resources of science and the various engineering disciplines based upon it. The subjective factor of the labour process is removed to a place among its inanimate objective factors. To the materials and instruments of production are added a “labour force”, another “factor of production”, and the process is henceforth carried on by management as the sole subjective element.

And progressively, these “labour processes” (market-values) subsume our whole lives – sport, leisure, learning, family – the lot. Everything becomes a capitalist surplus-creating process.

If we judge all human endeavour and activity by whether they are of value in a sense that we judge private profit making then we will limit our potential and our happiness.

One of the bulwarks against this descent into a narrow dog-eat-dog (but the richer dogs ensure they get their subsidies from the public trough before anyone else) trend are the humanities and critical thinking.

The role of education therefore is to broaden our perspectives and not to create us as servants of capital with only a commercial aspect.

The Atlantic author wants “liberal arts departments” to be transformed to ensure students have “access to business role models and public/private partnerships can fundamentally transform the way we think about workforce development”.

But beautiful music is intrinsically non-commercial. Aesthetics stand apart. We might want to commercialise them – and so an entrepreneur will. But the artist might just like painting and the rest of us might just like looking at them in free entry public galleries.

We might go homefrom an exhibition more calm, happier and be nicer to our families. We might then appreciate nature more and see the rivers and the beaches and the rest of it beyond the shopping centres and the board rooms.

The Atlantic author wants to:

… fire every college president with the means and resources to embrace entrepreneurship who doesn’t explore, support or start an entrepreneurship education program or partnership of some kind.

In proposing that he seeks forgiveness for not shedding “a tear for those leaders whose outdated policies” which “helped create the situation we’re in today”. Again conflating a symptom with the problem.

Business schools and financial entrepreneurs created the problem that the world is caught up in today. The solution is not more of the same.

Conclusion

This blog just continues my theme against the commercialisation of education and the need to see our schools and universities as preparing us for broad roles serving humanity not shareholders. The latter can take care of themselves.

We also need more artists and fewer entrepreneurs. The financial entrepreneurs have produced nothing of value. In fact, they have destroyed commercial value over the last 20 years and contributed nothing to the aesthetic of life.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I absolutely agree 100%. See, there’s plenty we agree on Bill! 🙂

I dont know if you can find time to read long screeds that bloggers like me post so I will pluck one point out of my last post and ask if you agree. Its points out that Neoclassical economics falls for the Reification Fallacy.

Mainstream neoclassical economics uses the technical financial-economic approach in a selective, ideologically conditioned and unempirical manner. The outcome of this neoclassical approach is to mystify money, finance, national accounts and macroecnomic measures in ways which obscure certain features of reality and conversely makes out that some things are “real” when they are in fact not real. Mainstream economics jumps at shadows. In other words, I am talking here of the Reification Fallacy “also known as concretism, or the fallacy of misplaced concreteness”. “An abstraction (abstract belief or hypothetical construct) is treated as if it were a concrete, real event, or physical entity.” I take the definition and explanation from Wikipedia.

Dr. Mitchell,

Your semi-digression today is well appreciated. I’m glad you’ve found time to continue your blog.

A fascinating departure from your normal topics. I found it especially resonant, as the merit of certain degrees and lack of technical training have been sources of much debate in our office lately.

However, it does appear that in the UK (particularly in the Oil and Gas industry) there exists a skills shortage. Immigration, mainly from Easter Europe, has often managed to bridge this gap. But recently companies claim they now have to look to countries such as the Philippines for available skilled labour.

Does this not suggest that some level of “social engineering” (i.e. in this case, guiding more into technical and vocational style training) can benefit the economy? I accept it would make only a minor dent in the unemployment figures (as the ratio of unemployed to reported vacancies is in the region of 10 to 1), but it would be an improvement – would it not?

Outstanding blog!

I cannot find words to praise it and, of course, the author as they deserve.

Professor Mitchell is for me not just an indefatigable genius in economics but a superb writer, highly cultivated humanist, and philosopher as well; he provides invaluable service in behalf of social welfare. He enriches my mind — and my life — each day.

I am very grateful to him for that.

Thanks Frederico Carvalho – I totally agree with you and could not have said it better!

“Trying to solve the problem by people “creating their own jobs” is to descend into the fallacy of composition “

Well, I think there is still some sense to this, if one construes it as … finding ways to call forth money from savings. If the race of entrepreneurs is to find ways to screw the other entrepreneur or larger business out of some money, then it is a zero sum game without any global consequence (except perhaps to gain efficiency and free labor for artistic uses in the future).

But if the putative entrepreneur creates a furby that calls forth net savings- something so compelling that other economic needs are not sacrificed, but money flows directly from savings to new spending, then new employment may be created and net economic growth result.

Unfortunately, this is not even on its own terms a sustainable policy. People do want savings, and at some point the balance between savings and spending will re-equilibrate and no matter how compelling the product, sales will be limited to income. The solution then is financial engineering to allow consumption with negative savings… another story!

Thanks for your work!

I can mostly agree with this of Bill’s posts.

Indoctrination of future decision makers during the years of their formal education has produced the present mind set and influenced policy in various fields of government and business. Particularly, the importance of e.g. the study of history can not be over-emphasized.

The only real difference lays in the cause of the present malaise. Bill does focus simply on the seemingly inadequate response to the present crisis by the decision makers whereas I would rather put my focus on the root cause of why this crises occurred. I am looking for the reasons of all these ever growing imbalances and what policies or institutional mal functions led to those results so that the present reaction by decision makers are rather the treatment of symptoms without really acknowledging the actual decease.

In response to R Teperek,

I doubt Bill would have much issue with the form of social ingineering — that is directing and using government and its resources to direct people in certain directions, and providing them with the support and resources to meet those goals.

While I don’t doubt that there is a shortage of these sort of skilled labor in the UK, and certainly in the US as well, this is a result of policy decisions. It takes a long time, and often a lot of money to get these sort of degrees, and the government/state support that formerly existed doesn’t exist. The second problem is that these are degrees that have declined in importance with the rise of finance, and much of the R & D budgets and departments have declined with them. Both government and private investement in R & D has been declining in the West and many of the research labs have closed down, so why are people going to be going into these careers?

This isn’t to say we don’t need these people, but these are jobs that take time and committment and aren’t necessarily valued all that much, and have suffered in a decline in investment in them. Relative to other careers, these have been left behind in terms of pay and job advancement, and the people who would normally gravitate towards these jobs have been pulled elsewhere.

Also response to R Teperek,

Why should the sole responsibility for skills training fall on the shoulders of the individual or state? Businesses know what skills they need, why don’t they run a scholarship program to encourage the development of the skills they need? This mind-set reminds me of the documentary The Corporation, which argued that corporations continually press to move as much of their costs onto the public sector as they can, to maximize their profits. Having done so, they then complain that the public sector is not doing ‘enough’ to serve their profit-making needs.

“Businesses know what skills they need, why don’t they run a scholarship program to encourage the development of the skills they need? ”

Because other business nick the staff from those who do the training. So competitive pressure removes training and long term staff development from the table.

Our society should not be relying upon businesses to do anything other than exploit labour for their own ends.

Individual’s livelihoods shouldn’t depend on individual businesses, their pensions should have nothing to do with businesses and their personal development should not depend on a business.

Businesses come and go. They are increasingly ephemeral institutions that drive things forward for the short time they exist.

The long lasting institution of society must take on the development role and leave business to their profit.

Re the comment by Neil Wilson, the long-lasting institutions that come to mind are those associated with government. And it is some of these very institutions, particularly entitlements, that the Republicans, now rubbing their hands in glee, feel they can cripple if not destroy. Part of Bill’s piece reminds me of Keynes’ article on his grandchildren. But without government intervention, Keynes’ vision will never materialize.

While, strictly speaking, not directly on the topic Bill has brought up, a terrific speech that Kennedy gave to a public rally about US health care and other “entitlements” is worth watching, even if the US has hardly gone anywhere with many of these issues so far. Here is the link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ILqHSH4X_w. It needs to be watched until the end. There is an amusing comment about the rich that occurs near the end.

If we generalize Bill’s and Neil’s points, health care and medical education are two of the long-lasting institutions that can not be left to business, entrepreneurial or otherwise. However, even if government wants to help, this help may not be wanted. I was once part of a task force while a grad student looking into government support of medical education. One of my tasks was to read the congressional hearings about reactions of the medical profession to the government proposal to support medical education. What the government wanted to do was to support medical libraries and labs while not interfering in any way with how the funds that they would distribute would be spent other than that they would be spent on books, journals, and lab equipment. Invariably, top medics and the AMA cried that this was nothing short of an instance of creeping communism. While this debate took place in the fifties after McCarthy, though still persisting in different forms, I could hardly believe what I was reading. I considered their reaction to be an instance of a kind of hysteria. When I mentioned this to other task force members more senior than me, all they did was shrug their shoulders. Many of the senior task force members were also members of the elite and this reaction appeared to be their default reaction to the “peccadilloes” of other members of the elite.

Thanks for the responses to my question.

Repeating myself here..

I think we can all except – from looking at the ratio of those who want work to job vacancies – that the private sector is failing in its “duty”. However, in the UK, it is also true (I think!) that businesses have struggled to fill technical-based roles (especially in the Oil and Gas sector – in which I work.) As a result, they have had to fill these vacancies with immigrant labour.

Doesn’t that suggest that, in just these cases, the public sector has failed to provide for the private sector? While I agree with Keith W that technical-based careers have declined in status and remuneration compared to jobs in finance, technical jobs in Oil and Gas do provide good pay and, in many cases, excellent pay when compared to the non-finance sector.

As Keith W said, technical apprenticeships and degrees are expensive in both time and money. But, and this returns to Bill’s blog, if there are so many people going to university anyway, would it not be better to have a higher proportion of them studying technical subjects, rather the humanities and media studies? I accept would be merely a ‘drop in the ocean’ and would not address the underlying economic fault-lines, but surely it would have reduced unemployment somewhat.

“would it not be better to have a higher proportion of them studying technical subjects, ”

They are, but are being hoovered up by the financial sector as ‘quants’, etc.

If we want the technical staff doing real work we need to do something about the casino in central London.

@ Neil Wilson;

What practical measures would you recommend for shrinking the London casino and re-balancing the UK economy?

Let’s start with a proper Job Guarantee and take it from there.

Thanks for the very interesting reading…

In my country Portugal the “entrepreneur hype” is reaching curious levels during the EURO crisis, they are tring to teach little children to be entrepeneurs now :

http://boasnoticias.clix.pt/noticias_livro-infantil-incentiva-empreendedorismo-desde-cedo_14189.html

( in Portuguese )

Funny fact is that Portugal had more “entrepreneurs” ( many of them are actually service contractors – or employees without benefits ) than most European countries and that didn’t seem to help much our economy.

http://www.eu-employment-observatory.net/resources/reviews/EEOReview-Self-Employment2010.pdf

Casino capitalism will rebalance itself enventually. Excessive parasite loads die when they kill the host.

At Jose Ramos

I can understand your frustration. If only the politicians would have had the guts to repudiate the unpayable debt and show the foreign banks their middle finger. However it might be too late already by now as probably most Government debt is with the local banks. This is the real misery, namely the fact that at the beginning of the crisis a real solution was delayed and delayed allowing those who originally granted credit without the corresponding due diligence were able to escape with the loot.

“This generation is less likely to build up adequate superannuation balances to assist them in a reasonable retirement. They are less likely to be in a position to purchase property – which remains the primary way that the average household generates wealth over their lifetime.”

By “superannuation balances” you must mean “savings for retirement”. There’s no reason why this generation, like any previous one, shouldn’t be able to save and invest some of its income for future expenses. Of course they might have to forego some consumer spending, perhaps live in smaller digs, do a little more home cooking but that’s an individual choice, a matter of time preference. Additionally, just as in most jurisdictions parents are responsible for the upkeep of their children, why aren’t children legally responsible for maintaining their parents? What possible form of warped logic allows a child that has been supported for at least the first 18 years of its life to ignore the needs of a parent in its decline?

How does the purchase of property generate wealth over a person’s lifetime in the absence of improvements? There’s been a nearly world-wide inflation and bursting of residential real estate prices yet you’re still saying that counting on the steady increase of property values makes sense. Millions would emphatically disagree.